SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – March 21, 2018 is a historic day for the Philippine National Police (PNP) Academy.

It was graduation day for the premier police school’s Maragtas Class of 2018 – 108 cadets were crossing over from the place they had called “hallowed grounds” to the endless fields outside Camp Castañeda’s walls.

In a rare occurrence, the country’s top two officials, President Rodrigo Duterte and Vice President Leni Robredo stood side by side at the school’s grandstand stage, its apron laced with pink and white anthuriums.

A rarer event, however, happened just a few hundred meters away inside the camp – the PNP Academy’s new white dormitory. Inside, junior cadets mauled 6 fresh graduates until they bled.

The story was picked up only days later, after the PNP Academy’s director, Chief Superintendent Joseph Adnol, broke his silence to police reporters. The story was a scandal, as beating an upperclassman is unimaginable in the highly hierarchical PNP Academy.

Adnol downplayed the incident, calling it an “isolated case.” Chilled by the beating too, the PNP Academy alumni association called it an “act of violence”, adding that it “has no place in the Academy, more so in a civilized society.”

Their attempt to sugarcoat the scandal, however, somehow remained futile.

A bold and frank PNP chief, Director General Ronald dela Rosa, readily admitted in a news conference that beatings inside the academy have become a “tradition.”

A video also surfaced showing that beatings were executed in the PNP Academy back in 2017.

It promotes a “cycle of violence”, Dela Rosa said, that has in fact long found its place in the PNP Academy – contrary to how its director and alumni wanted to paint it.

Rappler interviews alumni from different batches of the PNP Academy, revealing how they experienced the violent culture inside, and how a treasured tradition ended in tragedy.

Tradition across generations

No two alumni of the PNP Academy have the same stories of violence inside Camp Castañeda, but the beatings have always had two things in common before the 2018 mauling:

- It was delivered by upperclassmen

- It was used for discipline when cadets made mistakes in training or house rules

PNP Human Resource and Doctrine Development (HRDD) chief Director Cedrick Train told Rappler that back in the early 1980s, beatings were done by upperclassmen “only when they held a baton.”

“Hindi natin maiiwasan ‘yan, meron talagang minsan namamalo (You can’t avoid that, there really is sometimes someone who will hit you),” said Train, an alumnus belonging to the PNP Academy batch 1984, among the early batches.

When seniors held nothing to hit lower-class cadets, Train said, they simply ordered strenuous exercises like push-ups.

Meanwhile, a source privy to the 2017 beatings caught on video said that blows have recently been regularly delivered almost every night after the day’s mistakes have been tallied.

The latest system apparently worked like this: The more mistakes you make while the sun is out, the more hits you take when the sun comes down.

“It isn’t just a tradition. Inside, they aim for perfection. Most of the time it happens in secret,” the source of the video said.

It’s a tradition that is apparently shared across PNP Academy batches between Train and the now-commissioned officers in the 2017 video.

“Ako sinuntok ako sa tiyan para makita kung matigas ba pagkatapos magkamali (I was punched in the stomach to see if [my gut] was tough right after I committed a mistake),” said a PNP alumnus who graduated in the early 1990s.

An alumna from the late 1990s, meanwhile, shared her worst beating experience: “Pagkatapos kong ma-mersonal ng mga upperclass, inaraw-araw ako sa talampakan, sa puwet. (After I attacked my upperclassmen personally, they hit me every day at the soles and at the buttocks.)

Here’s the twist: Despite having to bear the beatings inside Camp Castañeda for years, the alumni did not despise the beatings or their beaters. Most of them were even thankful.

Beating with meaning

In explaining their tradition, all of them drew a parallelism with disciplinary violence inside homes.

“When you were a child, weren’t you spanked by your mother?” asked the alumna from the late 90s.

“For me, it’s the same as what’s done inside the house, you need disciplinary action, just like your mother spanking you in the behind,” said the alumnus from the early 90s.

“Spare the rod, spoil the child,” said PNP’s Train. “Even Rizal said this, right?”

A critical part of the PNP Academy beating that is always left out, Train pointed out, is the scolding. The beater should explain to the victim why there was a beating in the first place.

“Kung mananakit ka, kunwari nanakit ka ng maliit na bata, ipo-process mo (If you hurt someone, for example, a small child, you should process it),” Train told Rappler.

The alumna from the late 90s said that when their batch became the new upperclassmen, the processing of beatings was called a “pep talk.”

“Parang sesermonan namin, tatanungin namin after mamalo: ‘Ano? Saan ka nagkamali? Bakit sa tingin mo pinalo ka?’ Usually alam na nilang nagkamali sila kaya mas hindi nauulit ang sablay,” the alumna said.

(It’s like we’re delivering a sermon. We would ask after the beatings: ‘Where did you think you committed a mistake? Why do you think you were hit?’ Usually, they already know that they committed a mistake so they end up committing wrong less and less.)

“After n’on (pamamalo), gawin ‘yung talk kaagad. ‘Wag ‘yung sinasaktan mo tapos iiwan mo. Magtatanim ‘yun ng galit. ‘Wag power trip,” the alumna said. (After the beating, you should talk immediately. Don’t make them suffer then just leave them. They will hold their grudges. Don’t go power tripping.)

It’s the meaning that came with the beatings that apparently molded the character of cadets – a sentiment shared by no less than PNP chief Ronald dela Rosa.

For the alumni, the beatings make sense against the backdrop of what they proudly call the “regimented life” – a life restricted by rules like waking up every day at 5 am, eating only when upperclassmen decide it best, and sleeping only when the lights are turned off (there are instances when they apparently aren’t).

All the rules serve a clear purpose: shaping the model police, jail, and fire officers.

The purpose that accompanied the painful beatings, however, has supposedly faded as the years went by.

Purpose lost

The 2018 graduation mauling marked the worst in terms of the tradition’s deterioration.

“Kaya may galit ang underclass sa kanila kasi sila (batch 2018 cadets) ‘yung mahilig magpareport at magpadisiplinina sa ayos, minsan wala na sa ayos yung pagreport nila,” the source said.

(The reason the underclass were angry at the cadets from batch 2018 is that they were fond of asking cadets to report to them then beating them. Sometimes their reporting and beatings were already out of place.)

The motive matches with what PNP Academy director Adnol released to reporters: The underclassmen held “personal grudges.”

The links also speak for themselves.

Probing the video and the graduation mauling, Philippine Public Safety College (PPSC) President Ricardo de Leon told Rappler that they have identified two cadets who delivered blows in the 2017 video and who were also victims in the 2018 mauling: Police Inspector Ylam Lambenecio and Police Inspector Arjay Divino.

Of the 6 victims, they are the only two who filed criminal complaints against their alleged maulers.

The mindless violence inside the academy has apparently become an unbearable culture for some cadets, the source of the 2017 video said, such that when the tradition of dunking graduates in academy swimming pools came in 2018, they added hits from rocks and paddles.

No repeats, they promise

While it’s the first time that underclassmen pounded their seniors to the ground while the President and the Vice President were on the academy’s grounds, it’s the most recent time that the spotlight was cast on the PNP Academy because of violence.

In 2000, Dominante Tunac died of pneumonia, 3 days after collapsing from hazing rites inside the academy. In 2003, Geoffrey Andawi died of traumatic head injury after upperclassmen beat him unconscious inside one of the school’s bathrooms.

According to PPSC President De Leon, a Philippine Military Academy graduate, he has tried to end the violence inside the PNP Academy ever since he assumed office in 2014, but cadets seem to have clung on to the culture, he said.

“There is a culture that has been developed which could be passed on,” De Leon said.

“It’s the senior classes that dictate the tempo. We have cut violence from them, so why does it keep on returning?” De Leon said.

According to De Leon, he has implemented at least 3 changes in the PNP Academy to prevent more cadets from sending fellow cadets to the hospital.

First, he said, was building the new white dormitory which aimed to “create an environment conducive to learning.” As it turns out, the building that houses the dormitory is where the 2017 and 2018 beatings occurred.

De Leon also shifted the focus of training inside the school to academic learning and character development by establishing 4 academic departments. This, he said, was intended to keep cadets focused on their studies aside from doing intense fieldwork.

The effect of the curriculum shift has yet to be determined, he said.

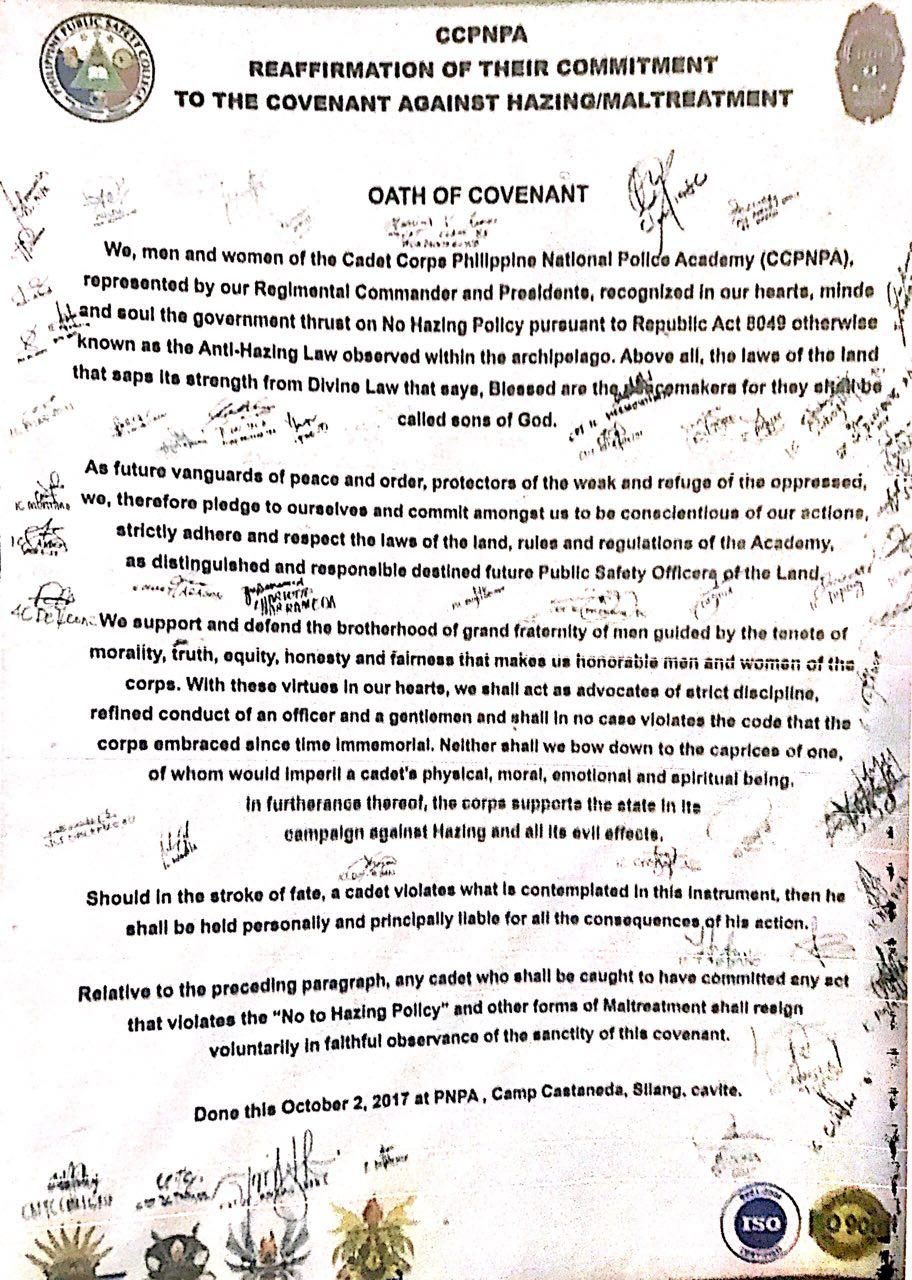

The effort De Leon was proudest of all, however, is the crafting of a “Covenant Against Hazing or Maltreatment”, which he has made cadets sign during the PNP Academy’s anniversary celebration every October since 2015.

The covenant starts: “We, men and women of the Cadet Corps of the Philippine National Police Academy…recognized in our hearts, minds, and soul the government thrust on No Hazing.”

“We shall act as advocates of strict discipline, refined conduct of an officer and a gentleman and shall in no case violate the code that the corps embraced since time immemorial,” it continues.

“Should in the stroke of fate, a cadet violates what is contemplated in this instrument, then he shall be held personally and principally liable for all the consequences of his action.” – Rappler.com

Top graphic by Ken Bautista/Rappler

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.