SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Hunger is said to be the world’s ‘greatest solvable’ problem. This global problem, however, still persists until today.

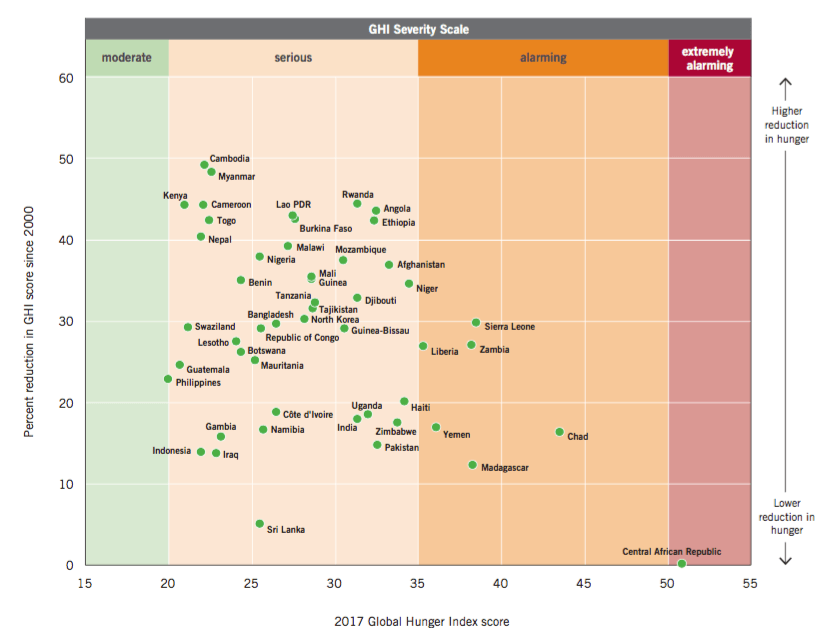

According to a report by the International Food Policy Research Institute in 2017, the Philippines had a global hunger index of 20.0 percent, ranking 68 out of 119 countries. While this indicates a decrease in hunger incidence by 0.2 percent since 2008, the country’s hunger threat still falls under serious levels.

Numerous efforts have been done to address hunger and malnutrition in the country within both public and private sectors. However, initiatives remain scattered, thus slowing the entire process of solving the problem.

House Bill No. 3795, later adapted as House Bill No. 7193 or the Right to Adequate Food Framework Bill, was filed under the vision of having a comprehensive law specifically for addressing hunger and food insecurity. The bill’s provisions require cooperation among all government units, working towards a more unified approach. (READ: PH Zero hunger bill takes center stage)

One of the critical aims of the bill was to end hunger within 10 years, gaining the title ‘Zero Hunger Bill’. This is in line with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals of ending all forms of hunger and malnutrition by 2030.

The Zero Hunger Bill was first proposed in 2014. Four years later, its passing is yet to come to a fruition. The question remains: Why the long wait?

Obstacles in legislation, recognition

If hunger has been a long-standing problem, why are administrations – past and present – not keen on the immediate passing of the bill?

Ibarra “Barry” Gutierrez III, principal author of the Zero Hunger Bill, attributes the slow progress to many obstacles, both political and economic. One of the main reasons is funding, especially in terms of the creation of a new commission dedicated to the food problem – the Commission on the Right to Adequate Food.

Much like any other proposal for a creation of a new office, there is hesitance because of the additional expenses it might cause. However, authors of the bill argue that the new commission is essential, should we want to ensure more accountability and action. (READ: $267B more needed each year to end hunger by 2030 – UN report)

The Zero Hunger Bill is patterned after Brazil’s Fome Zero program that adapted a ‘whole-of-government approach’ from the president down to the grassroots. Moreover, the program allowed for the creation of a National Food Commission. They were able to eradicate hunger. (READ: Lessons from Brazil’s Zero Hunger Program)

While the the House Committee on Appropriations has already approved the funding provisions for the bill on October 18, 2017, the source and specifications of financing remain unclear.

“Na-approve ‘yong (The) funding provision (was approved) but it’s approved in the sense that’s to be provided for in the [General Appropriations Act],” Gutierrez noted.

Currently, the bill has made its way to the Senate. The problem now, however, is the inter-agency referral system of legislation. The bill was referred to the committees on human rights, finance, and justice, and discussions for these take time. (READ: Pimentel hits Alvarez: Senate not slow, it’s Congress’ ‘critical chamber’)

“It’s harder every time a bill is referred to more than one committee. Kasi the 3 committee chairs have to agree (on hearings), which is a more bureaucratic and, therefore, slow process,” Gutierrez said.

Is food a right?

Going beyond the legislation, the biggest hurdle may be the recognition that there is, indeed, a right to adequate food.

“I think the hesitation is, ‘okay, if there’s a right to food, does that mean that government should be providing it?’” Gutierrez said.While the Right to Adequate Food Act promotes inter-agency cooperation on implementing certain provisions, this does not necessarily mean that the government must be the primary producer of food for the people. According to Gutierrez, what the bill wants to promote is for the government to begin and to aid the process. (READ: Zero Hunger: Holding gov’t responsible)

“It is the government’s duty as the obligation-bearer to the right to food to create an environment or, at least, to have a program to ensure na ‘yong access na ‘yon (that access) is present,” he added.

For FoodFirst Information & Action Network (FIAN) – Philippines president and National Food Coalition convener Aurea Teves, this misrecognition is one of the main reasons for poor progress as “development goals of the government have considered food more of a need, rather than a right.”

This has subjected food to more “technocratic” processes, which has led to slower and inadequate delivery of resources. (READ: Group urges gov’t to act on food insecurity amid economic ‘growth’)

Access to food, land, and overall nutrition is another issue. Despite the 6.8% gross domestic product growth of the Philippine economy during the first quarter of 2018, the decrease in hunger and poverty incidence remains at a snail’s pace. (READ: Hunger up in Metro Manila, Mindanao in Q2 2018 – SWS)

For instance, underweight prevalence may have gone down in majority of the regions in the previous year, but the rates are still high within Bicol region, Eastern Visayas, and MIMAROPA. There is also an increase in the number of underweight Filipinos in Western Visayas.

“Due to low rural incomes, lack of access to productive resources and vulnerability of the countryside to various shocks related to climate and diseases, hunger is more prevalent in rural areas. Women and children suffer most from hunger and malnutrition,” Teves said.

More waiting but hope remains

The bill’s authors as well as food advocacy groups remain hopeful that the 10-year target of zero hunger is still possible. However, it all depends on the leadership and commitment of the government – especially of the future leaders of the Commission on the Right to Adequate Food. Strict implementation of the provisions contained in the bill is necessary to achieve its goals.

Currently, the bill is under the Senate, and discussions are still underway.

“The Right to Adequate Food Framework bill, which is commonly known as the Zero Hunger bill, has been in Congress for quite a while precisely because it was not in the priority agenda of the Aquino administration before nor is it under the Duterte administration now,” Teves said.

Without prioritization in the midst of legislation, the passing of the bill continues to be far from reality.

In the meantime, food advocacy groups and the administration alike continue to provide feeding programs and other initiatives to prevent stunting and malnutrition.

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization acknowledges the role of legislation as “crucial” in improving the Filipinos’ quality of life.

“For countries to succeed, they must turn political commitment into concrete action. When food systems are more efficient, sustainable and nutrition-sensitive countries will have delivered on their promise to eradicate hunger in our lifetime.” – Rappler.com

Read more on this year’s Nutrition Month stories:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.