SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Part 4 of a series

Part 1: Panglao: Riding the tourism cash cow

Part 2: Garbage in paradise: The price of Panglao’s rise as tourist destination

Part 3: New system for old problems: Panglao’s struggle with solid waste

PANGLAO, Bohol – While tourism created a garbage problem for the municipality of Panglao, it’s also financing its new solid waste management system and environment conservation efforts on the ground.

Ian, a cinematographer who frequently dives around the country, had been to the renowned 5 dive sites in Balicasag Island to interact and take snapshots of sea turtles, schools of jacks, and barracudas.

“If you like sea turtles, then go to Balicasag. It’s known for its abundant turtle population and they grow to humongous sizes,” Ian said.

“The turtles are cool, they’re not afraid of people. Even if you slam into them accidentally, they’re just chill,” he added, noting that in some diving areas, turtles shy away from people. “Balicasag is one of the best places in the world for turtles.”

But Ian noticed what is “common” among other dive sites in the Philippines: the underwater scenery is a landscape of grays and coral rubbles. The coral reef in Balicasag is not as vibrant as other dive sites in the Visayas.

“Balicasag is not known for its corals,” he added. “If you dive, you’ll notice that there is evident environmental degradation underwater,” he said.

True enough, coral rehabilitation has been at the forefront of the municipality’s conservation efforts as resources from collected environment users’ fees (EUFs) are allotted for Panglao’s marine areas.

For coral rehab, fisheries

The degradation of corals can be attributed to a long history of fishing practices that are not sustainable, said Darwin Menorias of the municipal Coastal Resource Management Office (CRMO).

The coastal areas of Panglao are prime fishing grounds but through the years, the number of marine life has decreased. This, according to Menorias, was due to the degradation of the coral reefs in the area.

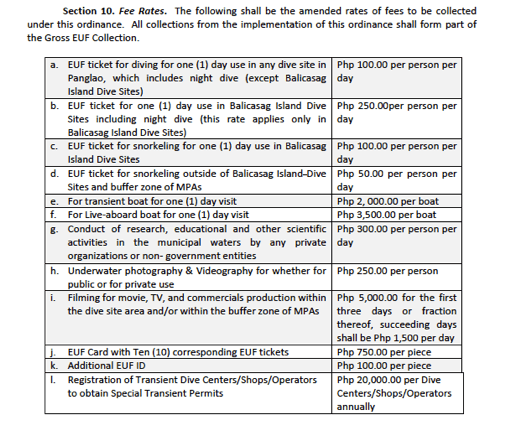

With legislative support from the municipality through Municipal Ordinance no. 12, series of 2014, the municipality started to charge EUFs for diving and snorkeling activities in the marine protected areas, including Balicasag.

The price for snorkeling was eventually amended through Municipal Ordinance no. 2, series of 2017. The new rates for snorkeling increased to P150 for Balicasag Island and P100 for other snorkeling areas in Panglao.

Registering 44,000 divers for 5 dive spots in Balicasag Island in 2017, the municipality earned approximately P11 million from environment fees alone. For the past 5 years, divers and snorkelers have been augmenting Panglao’s books, as the local budget rose to P167,647,061 in 2018.

The municipal share of the EUF gets clustered with the municipal treasury and a portion becomes part of the budget of the Coastal Resource Management Office, which eventually ends up for coral rehabilitation and marine life conservation.

Annually, during the International Coastal Clean-up day scheduled every third Saturday of September, the CRMO spearheads coral transplantation projects.

The first coverage area for the project was in Barangay Doljo in 2015. Though boasting of a long stretch of white beaches, the barangay’s 10,000-sqm marine area has only 10% live coral cover. After the program, the site had an enormous 80% live coral cover, albeit in juvenile stages in 2017.

“We intervened in that area because it’s 90% rubbles,” Menorias said. “After the intervention, we noticed a growing number of recruits of species but they are also small.” In the past, Doljo had damsels, which when fully grown, attract bigger fish.

By 2016, the coral rehabilitation turned to Barangay Libaong, whose location catches the yearly southwestern monsoon or habagat that mercilessly preys on the corals.

“The habagat causes an uproar underwater. After the waves crash on the shores and in the shallow parts, it does additional damage through backwash over the 3-hectare area,” Menorias said.

“When the waves hit the corals, they break. After the habagat season, you could already put in your pocket between 30-40% destruction,” he explained.

Last year, Barangay Bilisan became the priority area after a barge ran aground, causing 100% damage in the 2,000-sqm area.

Empowering the barangays

While in Balicasag Island, Ian didn’t notice any trash on the island and in the outlying waters. “The trash craziness is more noticeable on the mainland,” he noted.

True enough, Panglao’s beaches remain littered with garbage despite having a solid waste management system – and despite receiving allocations from the environmental fees.

The ordinance indicates how EUFs are to be allocated after making the necessary deductions:

- 40% goes to the Municipal Local Government Unit (MLGU). This allocation becomes part pf the general budget and is spent on priority programs.

- 30% goes to the barangays after they submit a specific Program of Works (POW).

- 25% goes to the Dive Site Management Teams and EUF monitoring teams.

- 5% goes to the Padayon BMT (Bohol Marine Triangle), a tri-municipality consortium that was created to protect the Panglao-Dauis-Baclayon Triangle.

Each of the 10 barangays propose projects for the allocations and since 2014 have been pooling their resources for barangay-level solid waste management systems.

Each barangay has received P393,581.62 for 2014 and 2015 respectively, but these were disbursed earlier this year only. According to Roque Cubar, the barangays have allotted these for garbage collection and managing the mineral recovery facilities (MRF).

The municipality is set to release an additional P764,659.14 to the municipality to cover the years 2016 and 2017.

The budget was used for the maintenance of the MRFs, manpower fees, transportation, and land rentals, as most of the barangays’ MRF are situated in public lands.

Aside from the EUF, barangays also have a 40%-share from revenues collected by the municipality on licenses, concessions, and other businesses related to fisheries, as mandated by the ordinance.

Given all these resources, why are barangays short-handed in managing waste within their jurisdictions?

Factors abound, including problems pertaining to late disbursement of funds and lack of designated land for the MRFs.

According to Manuel Fudolin of the solid waste management office, barangays grapple with monthly rent of private lands to house the MRF buildings as barangays have no allocated areas for solid waste management. Because of lack of space, MRFs are located beside barangay halls or within residential areas.

In addition, deficiencies in updated policies to support the direct downloading of funds from the municipality to the barangays create a lag in operations, made worse by elections.

Earning from tourism, losing on disposal

But while the barangays’ share of the environment users’ fees increased, the annual budget on solid waste management decreased.

The 2018 budget of the solid waste management office was based on the cost estimate projected in the 10-Year Integrated Solid Waste Management Plan. But the estimates were based on outdated projections since Panglao has accommodated more than P700,000 tourists and experienced more than a 1% increase in businesses since 2014.

(Click on the year below to see corresponding estimates.)

It’s not surprising that actual expenses incurred by the municipality are higher than allocations.

Panglao collected P777,520 from establishments in 2013 but spent P1 million on solid waste operating expenses. A year after, in 2014, collections increased to P937,330 while expenses on solid waste ballooned to P3 million.

This creates a push-pull effect for the municipality as it balances two things on the fiscal front: while it is strengthening its new waste management system, it is also financing the cost of disposing voluminous trash from tourism facilities.

Businesses in the municipality are paying annual collection fees of P3,000 to P4,000 each, a small price to pay since the amount of garbage has increased. Every week, Panglao spends an average of P4,500 in dumping fees at the Alburqueque Cluster Sanitary Landfill (ACSLF) for 3 tons of residuals.

“The municipality is facing a deficit in terms of waste management,” Fudolin said. “The total collections from establishments are limited and not enough to pay for hauling, manpower, maintenance, and dumping costs at the landfill.”

Private establishments also pose the biggest challenge to the existing solid waste management system: they do not strictly follow waste segregation rules set by the municipality. Worse, establishments are caught illegally dumping trash in vacant lots on the island.

The municipality then made a rule charging violators for every instance they fail to follow regulations in hopes of adding resources for waste disposal. Despite the charges, the habits remain.

“We still have a lot of recorded cases of non-segregation at source and we catch illegal dumping activities,” Fudolin said. “And every year, it’s the same establishments with the same types of violations.” – Rappler.com

To be continued: Conclusion | Erring establishments add to Panglao’s garbage woes

This story is part of a series on tourism and waste management in the Philippines, and was supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network (EJN).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.