SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

Roboto” rel=”stylesheet”>

AT A GLANCE

- The police does not criminally investigate the 5,050 deaths from police operations, citing presumption of regularity

- Of the 1,099 drug-related killings outside of police operations, only 327 have been “solved”

- Of the 20,000 or more overall deaths that resulted from the war on drugs, the justice department has prosecuted at least 76 only

- The human rights commission is dealing with an overwhelming amount of cases as they are kept in the dark by cops

MANILA, Philippines – The memory of the night Manny* was killed remains vivid in the mind of his mother Lita* one year later.

His lifeless body slumped on the ground with a pool of blood slowly spreading on the ground, turned the gray concrete darker in color.

It was 10 pm, a few minutes before the vegetables he was supposed to sell were due to arrive. But Manny did not live long enough for the next day’s marketing chores as a man shot him at close range, piercing bullets into his cheek and neck, killing him instantly.

Just like the perpetrators of several thousand other extrajudicial killings, the suspect was wearing a bonnet, rendering him unidentifiable to possible witnesses. It didn’t help that the act was committed at night and in a place where foot traffic is scarce after the sun sets.

The absence of a lead that could point to the gunman’s identity remains one of the biggest hindrances to Lita’s pursuit of justice for her son – even if she wants to file a complaint so badly, seek redress before a court, and have judgment rendered on the perpetrator of the killing. (READ: Powering through a crisis: Defending human rights under Duterte)

“Hindi ko alam kung sino ang kakasuhan ko kasi unang-una, walang nakakilala at takot rin kami kasi noong namatay siya, may nagmanman sa amin,” she said. “Pero kung mabibigyan ng pagkakataon, kahit saan ilalaban ko at kahit mamatay ako basta magkaroon ng katarungan ang anak ko,” Lita added.

(I don’t know who I will charge in court because first of all, no one saw or recognized him. And we’re also afraid because after he was killed, we felt we were under surveillance. But if given the opportunity, I’ll file a complaint and fight anywhere, even if I die as long as I give justice to my son.)

Until justice is served, the death of her son – which she likened to losing a limb – will continue to feel like a festering wound.

“Mahigit isang taon na pero hindi ko pa rin matanggap kasi wala pang katarungan,” Lita said. “Siguro mangyayari lamang na makakalimutan ko na iyong nangyari sa kanya, kung magkakaroon ng katarungan.”

(It’s been a year already but I still can’t accept what happened because there’s been no justice. Maybe I will only forget what happened to my son when there’s justice already.)

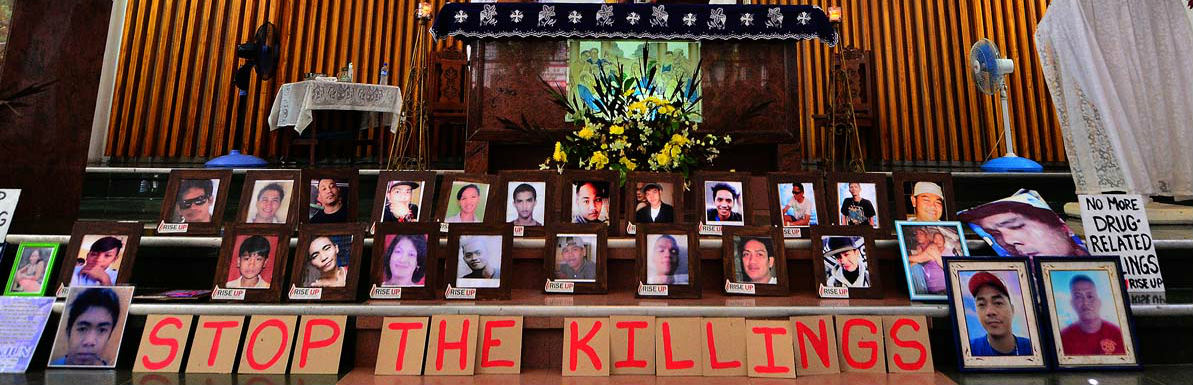

ALL DEAD. Photos of extrajudicial killings related to the anti-drug campaign are displayed at the altar during a Mass. Photo by Maria Tan/Rappler

Deterrents to solving crime

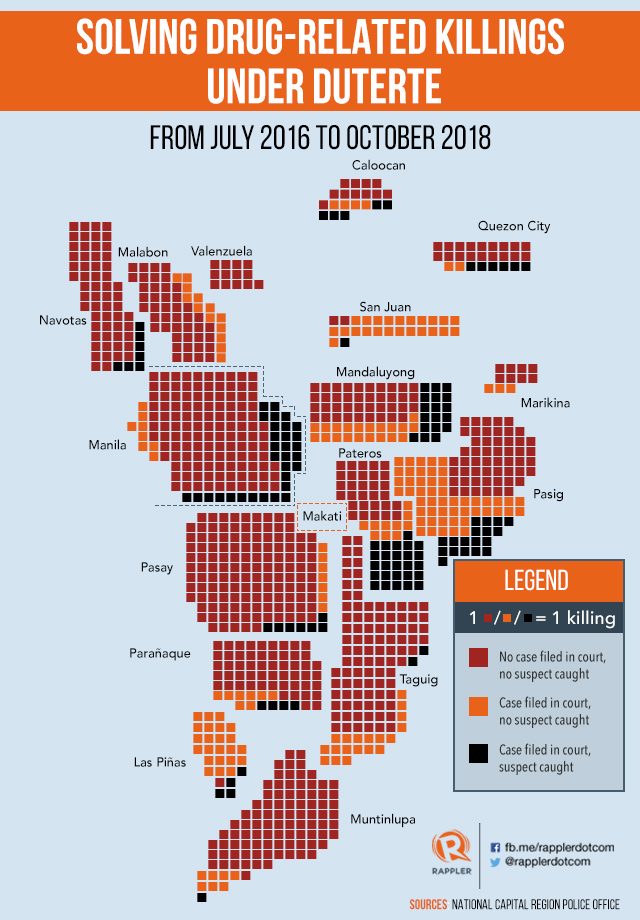

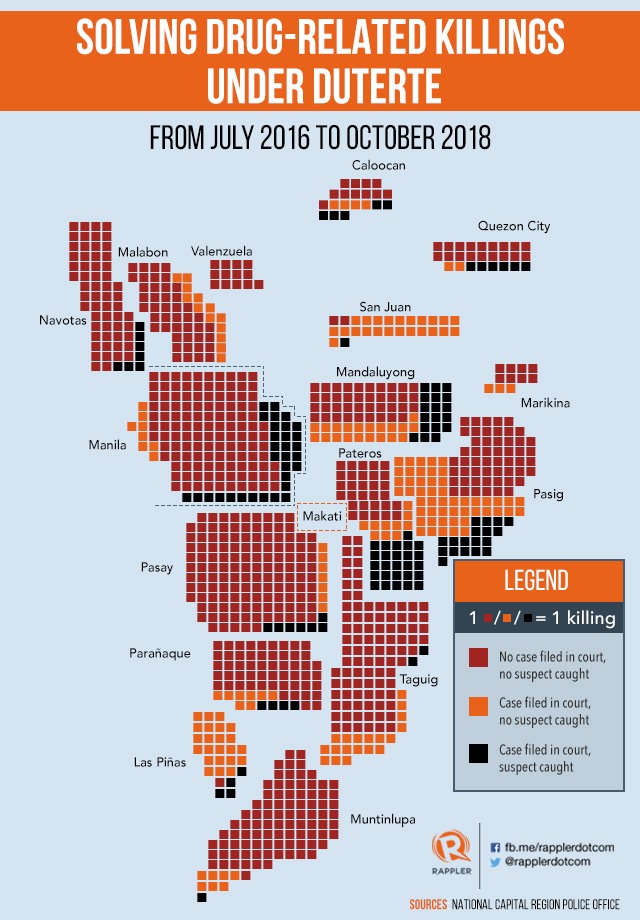

Manny’s murder is just one among the 1,099 drug-related killings outside of police operations across Metro Manila. The killings stretch from July 2016 (about a month after President Rodrigo Duterte assumed office) until October 2018, with numbers based on statistics kept by the regional police command in charge of the area, the National Capital Region Police Office (NCRPO).

Metro Manila is the nation’s capital. The cities and one municipality make up one of the most densely populated areas in the world – making it crime-prone.

Solving these drug-related killings has especially been difficult for Metro Manila. Of the 1,099 vigilante killings, only 327 have shown promising results: 131 have been solved and 196 have been cleared.

By “solved,” cops mean that a case has been filed in court and that at least one suspect has been caught. “Cleared,” on the other hand, means that there is already a case in court and at least one suspect has been identified. (READ: PNP says 125 cops punished for drug war-related offenses)

This means that a big majority of the drug-related vigilante killings, 70.2% of them, have not been filed in court and that no suspect has been identified.

We mapped the drug-related killings outside police operations during the first 26 months of President Duterte’s administration (see below).

The city of Manila registered the highest number of drug-related killings outside police operations, with its record standing at 161. Manila is where the presidential residence Malacañang is located, and where the administration’s so-called war on drugs was declared first in 2016. Of the 161 killings, only 8 have been cleared and 31 have been solved.

After Manila is Pasay, the city south of Manila which houses the country’s busiest airports. The city saw 149 drug-related killings, with only 7 cleared and 12 solved.

Despite its wide area and large population, Quezon City only counted 26 killings, with two cleared and 6 already solved. Financial capital Makati, meanwhile, recorded no drug-related killings outside police operations.

Pasig and Taguig rank no. 3 and 4 respectively in terms of drug-related killings outside police operations. The former tallied 122, while the latter counted 112 deaths.

Pasig has the highest number of cases filed in court without any suspects caught, recording 50.

Manila, meanwhile, saw the highest number of solved drug-related homicides, keeping a tally of 31. It is followed by Pateros, which, despite being the only municipality in the metro, has already solved 26 of the 68 drug-related killings in its area.

According to NCRPO Spokesperson Police Senior Inspector Myrna Diploma, the cases are moving forward at a glacial pace because their investigators want to be thorough before filing complaints.

Doing otherwise would risk dismissal at the prosecutor level.

“Dahil pinag-aaralan po namin nang maigi para maifile namin ‘yung kaso sa court (This is because we are studying the case carefully, so that we can file it in court,” Diploma told Rappler.

She admitted, however, that solving killings is especially difficult because “it involves the loss of a human life.” Besides, in high-level crimes, criminals usually have a deep motive and a detailed exit plan.

Diploma said homicide investigators usually end up facing a blank wall because of problems with witnesses. It’s not that there are no witnesses to the killings, but rather a case of them being afraid to speak up.

“Ayaw nilang madamay dahil natatakot nga sila or meron namang kilala nila kaya takot na takot talaga. Ayaw nilang madamay (They don’t want to be involved because they are afraid. There are some who know [the suspect] that’s why they’re really very afraid. They don’t want to get involved),” Diploma said.

Frightened witnesses are not new to policemen.

There are cases where witnesses could easily be tracked by culprits because of close connections, such as being friends or family. Then there are reported instances under the Duterte administration where families point to their local cops as having engineered the killings.

In 2017, Rappler reported on Tondo locals naming a cop as being behind killings of members of their community: Police Officer III Ronald Alvarez. When asked for comment, the Manila Police District just dared the witnesses to prove their claims.

Another reason why cases move forward at a snail’s pace is that the witnesses simply don’t want to be bothered with them.

“Then ayaw din nilang maabala. ‘Yun ‘yung number 1 pa, ‘yung ayaw nilang maabala. Siyempre kasi pag naging witness ka po is maga-attend ka po ng mga court hearing, so hindi sila makakapasok sa kanilang mga, kung may mga trabaho po sila, ganon po,” Diploma said.

(They also don’t want to be bothered. That’s the number 1 [reason], they don’t want to be bothered. Of course it’s because when you become a witness, you need to attend court hearings, so they wouldn’t be able to go to work.)

Drug-related cases are also more complex than the non-drug related killings. Cops face the challenge of having to crack the circumstances of the murders, besides also needing to keep an eye out for the drug groups.

Doing these, former Philippine National Police chief Ronald dela Rosa once said, could cost the lives of their investigators.

‘Awful numbers’

The 5,050 killings in police operations are not criminally investigated by cops because, according to them, they are covered by so-called “presumption of regularity.” This presumption, however, has already been debunked by a court conviction of 3 cops who murdered 17-year-old Kian delos Santos during a Caloocan City anti-drug sweep in 2017.

Human Rights lawyers also contest the same principle, saying that according to the PNP manual, deaths take away that presumption of regularity.

But where cops do not want to investigate, prosecutors should, according to a petition of the Center for International Law (CenterLaw) with the Supreme Court. Their petition seeks to declare the campaign against drugs unconstitutional.

The Duterte government confirms there have been 5,050 deaths from police anti-drug operations, as human rights groups peg the total death toll at 20,000 if deaths by unidentified assailants or vigilantes are included.

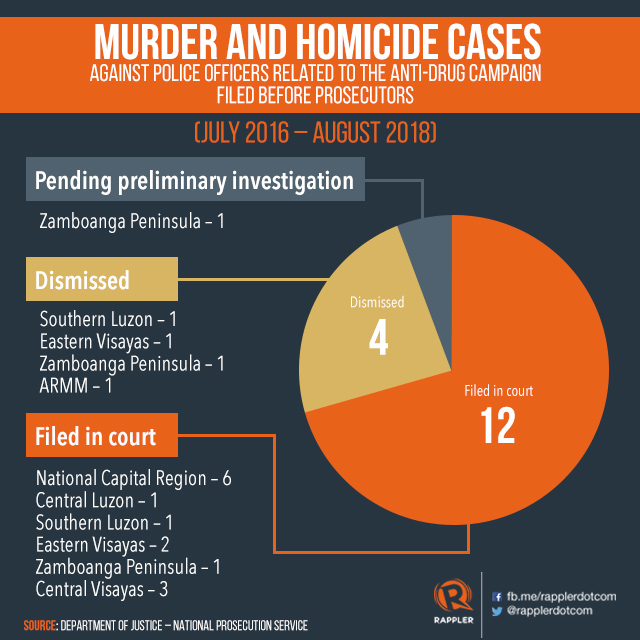

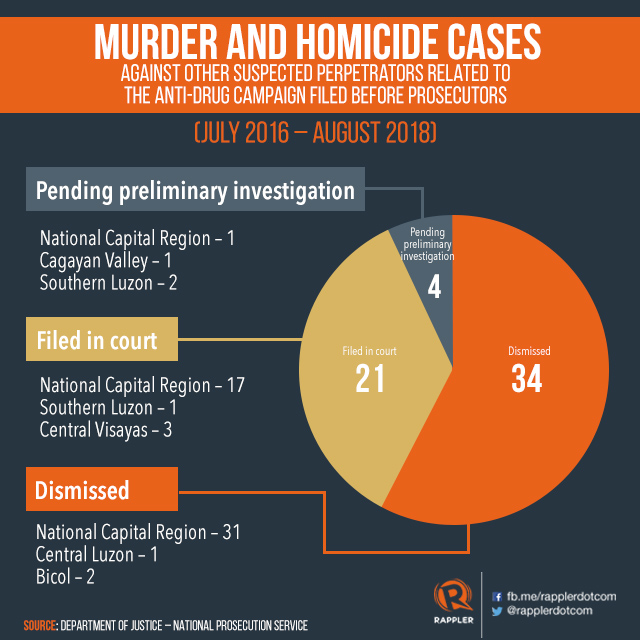

Yet Department of Justice (DOJ) prosecutors have only investigated at least 76 “murder and homicide cases allegedly related to the government’s campaign against drugs.”

“Extremely bad, awful numbers. It just goes to show that there is really massive killing that the government is not investigating and prosecuting and giving punishment to,” CenterLaw’s Cristina Antonio told Rappler. (READ: Lawyers do dirty groundwork to fight Duterte’s drug war)

The DOJ provided these nationwide numbers to Rappler in October 2018, collated from all prosecutors offices from July 2016 to August 2018. The statistics exclude numbers from Manila, Quezon City, and Taguig.

Rappler has been following up with the DOJ since October for the latest data, but as of January 10, 2019, the department has not provided updated information.

Of the at least 76 investigations, 38 were dismissed, 5 are pending before prosecutors, and 33 have been filed in court. (IN CHARTS: Drug cases take over PH courts, have low disposition rates)

This belies the persistent claim of the administration that they are investigating each and every death.

Justice Undersecretary Markk Perete points back to the police – the same police who claim that the deaths from their own operations no longer need to be investigated.

“Preliminary investigations (PIs) are conducted usually after evidence have already been gathered by law enforcement officers who then file before our prosecution service the relevant complaint and submit their evidence in support thereof,” Perete said.

Is the DOJ remiss?

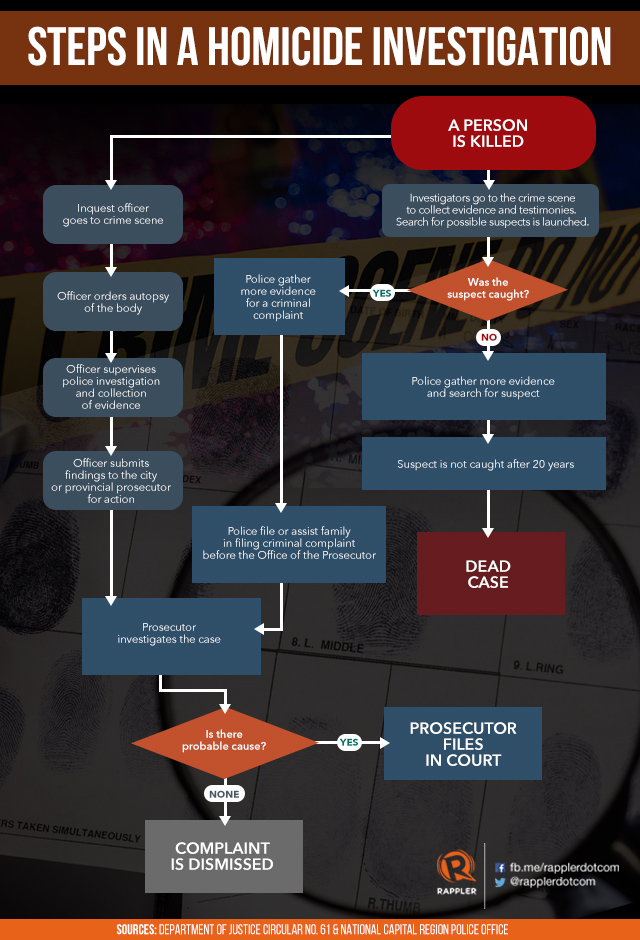

Antonio and CenterLaw want justices to take note that when a death happens, prosecutors do not need a complaint for them to act on it.

Section 16 of DOJ Circular No. 61 mandates prosecutors to rush to the crime scene “whenever a dead body is found and there is reason to believe that the death resulted from foul play, or from the unlawful acts or omissions of other persons and such fact has been brought to his attention.”

INVESTIGATION. Numbers provided by the DOJ belie the government’s claim that they are investigating each and every death. Photo by LeAnne Jazul/Rappler

Perete used the wording of Section 16 to defend prosecutors, and said investigations in the case of a death are not automatic:

SEC. 16. Presence at the crime scene – Whenever a dead body is found and there is reason to believe that the death resulted from foul play, or from the unlawful acts or omissions of other persons and such fact has been brought to his attention, the Inquest Officer shall… (emphasis ours)

“In other words, law enforcement authorities must inform first the inquest prosecutor of these matters for the inquest prosecutor to actually be involved in the investigation by law enforcement authorities,” Perete said.

Antonio attested that getting witnesses to come forward, much less file a case, has been a major challenge in seeking justice for those who died in the campaign against drugs.

That’s where Circular No. 61 comes in, as Antonio said the lack of witnesses should not stop an investigation.

“Naririnig natin na sinisisi pa ang members ng family na bakit hindi kayo mag-file ng cases in court. Baliktad (We hear them blaming families for not filing cases. It’s the opposite), it’s the police and fiscals who must prepare cases whenever there is a killing,” Antonio said.

Realities on the ground drive Antonio to suspect that prosecutors may be feeling “fear, because it’s difficult to go against a system, a concerted effort of not just individuals but state agencies.”

“I would like to think that our prosecutors are not complicit, I would like to think that being trained as lawyers that they have a love for the law and the Bill of Rights. I would like to think that what’s really preventing our prosecutors is mainly fear,” Antonio said.

Proving policy

What CenterLaw, and their co-petitioner Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG) are trying to do at the Supreme Court is prove illegal conduct by the police, in a bid to declare unconstitutional the entire campaign against drugs.

Two local cases help that bid somehow: the conviction of Caloocan policemen in the killing of teenager Kian delos Santos, and the acquittal from drug charges of a tricycle driver whom the police shot at, but who survived by playing dead.

But the decisions of trial court judges in those two cases are narrow, in that they fail to tackle whether or not the police operations in themselves were legal. In the Kian delos Santos case, Judge Rodolfo Azucena Jr of Caloocan even dismissed charges of planting of evidence against the convicted cops.

Antonio again directed attention to prosecutors.

“The judge may have been limited by what was given him, what framework was given him. It is the prosecution that prepares the case…the judge takes his cue from the evidence that was presented, the story presented by the prosecution so that may have been a factor,” Antonio said.

Perete said that “as far as we know,” cases filed so far have already prompted police to review or modify their anti-drug operation guidelines.

The PNP has revamped its anti-drug operations to address concerns of human rights violations, such as limiting the controversial Oplan TokHang to daytime only, and that all operations should be overseen by the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA).

“Both the PNP and Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) are in the best position to address any perceived loophole in their operations and policies, regardless of the breadth and scope of the Court’s decision in the Kian delos Santos case,” Perete said.

HUMAN RIGHTS. The Commission on Human Rights says the Philippine National Police is mostly uncooperative when it comes to investigations. Photo by Darren Langit/Rappler

Black eye on the state

The Commission on Human Rights is currently investigating 1,500 cases – a mix of deaths during police operations and extrajudicial killings – a number that Chairman Chito Gascon admits is not enough.

CHR, created through the 1987 Philippine Constitution, is mandated to investigate alleged human rights abuses by state actors such as the military or police. (READ: Things to know: Human rights in the Philippines)

The current setup of the Commission and lack of manpower are proving to be obstacles in keeping apace with investigations, especially with the high number of killings that have been recorded since the start of the anti-drug campaign.

“While there were human rights violations in previous administrations, they were not in the scale and pace that we see today,” Gascon said. “We’re also learning and unlearning.”

The current status of investigations conducted by authorities, including the PNP, is alarming, considering that it “has the responsibility [of] making sure that the violators [are] held to account.”

“Every single death that has not been solved is a black eye [on] the state,” Gascon said. “Even if they say that the victim is a drug pusher, that is still homicide, a crime, a death that needs to be fully investigated by the police.”

Now, the CHR has changed a lot in its operations to adjust to scenarios. For example, the police is no longer the “first point of call” of CHR investigators when it comes to pursuing complaints or probing incidents related to the extrajudicial killings.

Gascon said that if they approach the police first, it’s most likely that they will “face a blank wall.”

Thousands of drug campaign documents are kept in balikbayan boxes inside Camp Crame as the Philippine National Police prepares to submit the files to the Supreme Court in May 2018. Photos by Rambo Talabong/Rappler” />

Thousands of drug campaign documents are kept in balikbayan boxes inside Camp Crame as the Philippine National Police prepares to submit the files to the Supreme Court in May 2018. Photos by Rambo Talabong/Rappler” />PRECIOUS DOCUMENTS. Thousands of drug campaign documents are kept in balikbayan boxes inside Camp Crame as the Philippine National Police prepares to submit the files to the Supreme Court in May 2018. Photos by Rambo Talabong/Rappler

Cooperation between the CHR and the PNP has long been a matter of debate. The Commission’s requests for access to case folders related to the anti-drug campaign have been consistently rejected by authorities despite public promises made.

“We ask them, give us your files so we can also conduct our own investigations,” Gascon said. “If they give us files, maybe we can help speed things up but they are not giving us files.” (READ: Panelo says ‘simple’ to get drug war reports via FOI. It’s not.)

In the absence of cooperation from the PNP, the CHR has used its partnerships with several groups, including non-governmental organizations and churches, and even the media to help in the documentation of cases. They hope to double the cases they are investigating in 2019.

“That’s only a fraction of the deaths but if we do it well, are able to look at patterns that are emerging and identify common perpetrators, maybe we will be able to hold someone to account down the road,” Gascon said.

The Duterte administration has been stingy with information that even the Supreme Court (SC) has had difficulty getting documents on drug war deaths.

The justices were finally able to compel the government to turn over these documents in April 2018. Justices are still going through them, concerned whether the police reports exist at all, and if they indicate that the killings are state- sponsored.

The ICC

The systematic delay in solving the killings does not help the Duterte administration at all in a landmark legal battle before the International Criminal Court (ICC).

A total of 52 communications sent to the ICC allege that the killings amount to crimes against humanity.

Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda is examining the situation, but she will lose jurisdiction if it is proven that the Philippines is able and willing to prosecute the crimes on its own.

But is it, and is it doing enough? – Rappler.com

*Names have been changed to protect their identities

Top photo and Department of Justice facade photo by LeAnne Jazul/Rappler

Mass photo by Maria Tan/Rappler

Commission on Human Rights photo by Darren Langit/Rappler

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[WATCH] Dahas Project, the team that continues to count drug war victims](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/dahas-project-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=404px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Sorry Arnie Teves, walang golf sa kulungan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-arnie-teves-arrest-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=310px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.