SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE

- During the 2016 campaign, President Rodrigo Duterte vowed to return the coco levy funds to farmers in his first 100 days in office. But halfway into his term, he gave mixed signals and eventually vetoed the twin coco levy bills.

- Farmers felt betrayed because Duterte’s justifications for the veto were the very provisions they had been pushing for from the very start: a trust fund committee under the Office of the President and a 5-hectare limit for farmer beneficiaries to protect the poor.

- Until a law is passed, coconut farmers – among the poorest of the poor – are left with no option but to continue to toil daily while coco levy perpetrators bask in benefits.

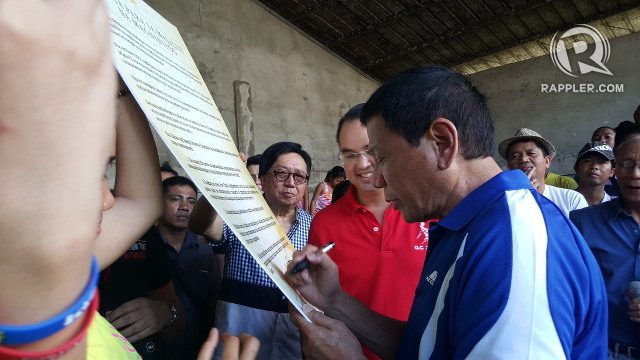

MANILA, Philippines – In 2016, farmers Rene Cerilla and Isabelita Escovilla witnessed then-presidential candidate Rodrigo Duterte promise the return of the multibillion coco levy funds. (READ: Coco levy fund scam: Gold for the corrupt, crumbs for farmers)

Farmers were full of hope that the decades-long battle for the return of the money to its rightful owners would finally happen. But 3 years after, the promise was broken with the veto of twin coco levy bills. (READ: Duterte, Cayetano vow ‘return’ of coco levy fund in 1st 100 days)

The veto, farmers said, seemed to have been Duterte’s plan all along. After all, they said, Duterte used the very provisions they have been pushing for – which have either been ignored or rejected by Congress and Malacañang – in justifying the veto.

“Tapang at malasakit. Nung iboto ito, nawala na ‘yung tapang niya. ‘Yung malas at sakit naidagan sa aming magsasaka,” said Cerilla, convenor of Kilus Magniniyog, referring to Duterte’s 2016 campaign slogan. (Courage and compassion. But when he was elected, the courage disappeared. The misfortune and pain were transferred to the farmers.)

“Hindi kami ganoon kabobo…. Ano ito lokohan? Naniwala kaming mga lider na nandoon noong nangako siya [Duterte] sa Catanauan, Quezon,” said Escovilla of the group Kalipunan ng Maliliit na Magniniyog ng Pilipinas or KAMMPIL. (We aren’t that stupid…. What’s this, are we fooling each other? We were there when he made that promise in Catanauan, Quezon.)

Joey Faustino, director of the Coconut Industry Reform Movement (COIR), said the poor farmers have been victimized by Duterte.

“So lokohan….Sabi nga ng iba, na-Duterte kami,” said Faustino, who was also with Duterte when he made the promise. (They fooled us….As others said, we were fooled by Duterte.)

The two bills were actually far from what the farmers originally wanted and proposed. They were starting to learn to live with it – “It’s better than nothing,” they said – when Duterte rejected them altogether.

“For many of us, it’s a betrayal of his promise,” said former senator Wigberto “Bobby” Tañada, a longtime advocate of the return of the fund to farmers.

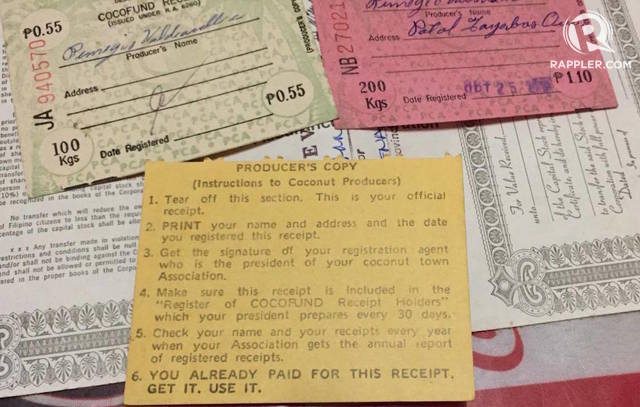

False hope?

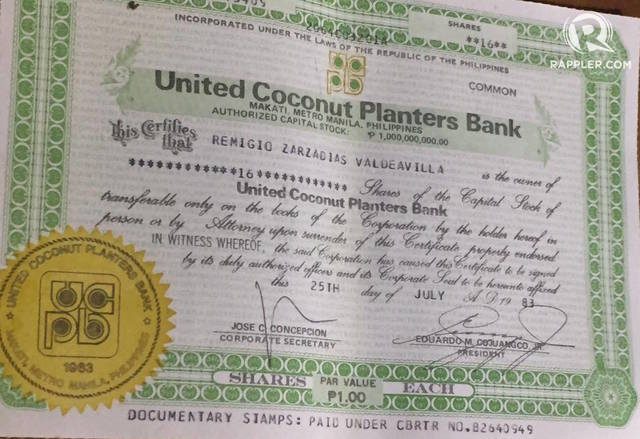

Farmers have been fighting for the coco levy funds for nearly 4 decades. The coco levy refers to the taxes imposed on coconut farmers from 1971 to 1983 by former president Ferdinand Marcos and his cronies, including former ambassador Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco Jr, former senator Juan Ponce Enrile, and former congresswoman Maria Clara Lobregat, among others. (READ: The politics of the coco levy scam: From Marcos to Noynoy Aquino)

They were promised “rewards” and benefits, but none came. Many have died waiting in vain.

The tax collections, amounting to P9.7 billion then, were used by Marcos and his cronies to set up or invest in businesses for their own benefit such as San Miguel Corporation and Cocolife, among others.

Once in power, Duterte gave confusing and mixed signals. Early on, he was first quiet about his promise. The next day, he pushed for it and included it in his State of the Nation Address. Then, without giving any clue on what the executive really wants, he vetoed the bills.

“Kailangang manikluhod sa gobyernong ito para magamit ang pera na galing sa aming bulsa. Pera mo na, nakikiusap ka pa,” said Jun Pascua of Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Makabayang Mambubukid. (We have to beg to this government for us to use the money stolen from our pockets. It’s your own money yet you have to plead.)

17th Congress: The twin coco levy bills

The farmers’ original proposal included the following key provisions:

- a 5-hectare limit on farmer representatives meant to protect the poor

- a trust fund committee, attached to the Office of the President, to manage the funds. This would be composed of more farmer representatives than government officials

- a perpetual trust fund

These provisions were altered following discussions in Congress, as expected in any legislative process.

The House of Representatives passed a bill that would create a trust fund committee – similar to what coconut farmers want. The bill, however, removed the maximum 5-hectare requirement for farmer beneficiaries, allowing even farmers who own big businesses and corporations to become beneficiaries.

The Senate, for its part, totally changed the essence and spirit of the bill. Senators voted to expand the Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA), instead of creating a trust fund committee, to manage the funds. Farmers strongly opposed this, as the PCA was the same agency responsible for the scam under Martial Law.

It was Senate President Pro-Tempore Ralph Recto who pushed for the amendment, saying the creation of another committee would bloat the bureaucracy and delay the process. But farmers said the measure would spread the PCA too thin, because its responsibilities are not limited to the coconut industry alone.

“Under the PCA, they are also tasked to develop the palm oil industry, which is the enemy of the coco levy because these companies were part of the scam,” said Pascua in Filipino.

In the end, the Senate passed the bill that granted powers to the strengthened PCA board, which would be composed of 6 farmers, 4 government representatives, and one from the coconut industry.

For farmers, the approved Senate version was already watered down. They had hoped to fight for their provisions in the bicameral conference committee, but to no avail.

Under the bicam-approved measure, both the crucial provisions on the 5-hectare limit and the creation of the trust fund committee were removed.

The bicam also included a sunset provision on the trust fund: the nearly P105-billion fund, at least P71 billion of which is in the treasury, will be distributed every year at P5 billion for 25 years or until it runs out. This was not present in the farmers’ proposal but they were amenable to it.

It was also during this time when lawmakers decided to pass a separate bill that would amend the PCA charter and reconstitute the PCA board. This meant Congress had to pass two bills for the return and use of coco levy funds: the trust fund bill and the PCA reconstitution bill.

On August 29, 2018, the Senate and the House ratified the bicam report. It was then sent to Malacañang for Duterte’s signature.

But lo and behold, little did farmers know it would be the start of the bills’ death.

Unusual second bicam to avert veto

More than a month later, Malacañang set the signing of the trust fund bill on October 9. The following events, however, were as confusing as they were dubious for farmers.

The schedule was canceled after Congress found out there was a presidential plan to veto the measure. Lawmakers met with Duterte before October 9 to convince him otherwise.

To avoid a veto, the House and the Senate adopted a resolution asking Malacañang to recall the enrolled copy of the bill, so they could amend it.

It turned out, according to Senate Majority Leader Juan Miguel Zubiri, that Malacañang opposed two provisions:

- The higher number of farmer representatives than government officials in the reconstituted PCA board

- The lack of a sunset provision for the P10-billion yearly appropriation to the PCA for the coconut industry

“What Malacañang opposes is that the management handling the fund will be composed of more civilians than government representatives. They said the funds, although it’s the fund of the farmers, it is in trust with the government so they are treating it as government funds. So therefore, the majority of the composition of the board should be government representatives,” Zubiri said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Farmer groups and advocates opposed this, saying coconut farmers should have a say because the money was stolen from them.

Congress adjusted the contentious provisions. Instead of having 11 members, the reconstituted PCA Board was expanded to 15 members, in favor of the government: 8 state officials, 6 farmer representatives, and one from the coconut processing industry.

Under this second version of the trust fund bill, farmers would receive P5 billion annually from the coconut trust fund for 25 years. On top of this, the PCA would also be allocated P10 billion yearly from the General Appropriations Act or the national budget, subject to congressional oversight review after 3 years.

Lawmakers said Duterte vowed to sign the amended bill. But it never happened and is unlikely to happen in the 17th Congress due to time constraints.

Congress doesn’t have enough time to fix the bills, as they are set to return one last time from May 20 to June 7, before adjourning for the 18th Congress.

Veto ‘excuses, betrayal’

The twin measures on the coco levy fund issue – the trust fund bill and the PCA reconstitution bill – go hand in hand. Without a reconstituted PCA board, there would be no mechanism for the use of the coco levy money.

Farmers questioned Duterte’s sincerity because he had not been transparent. They said Duterte had plenty of chances to relay his concerns. First, the measure was part of his priority legislations. Next, he mentioned it in his 2018 SONA. Lastly, he could have voiced those concerns when Congress recalled the measure.

“Malacañang is saying that his veto is meant to protect the interest of coconut farmers. But he wasted many instances when he could have specified what he wanted,” said Kilus Magniniyog, an umbrella group composed of 9 organizations.

Duterte’s veto of the PCA reconstitution bill was based on the following reasons:

- Under the bill, PCA is not required to seek approval from the executive branch. This means it has authority over the sale and dissolution of coco levy assets, which Malacañang opposed.

Malacañang says that under the bill, the only body with oversight functions over a reconstituted PCA is Congress. Not requiring executive approval makes the coco levy funds “susceptible to corruption akin to creating pork barrel funds.”

Duterte also thinks the bill gives the PCA too much power when it comes to managing coco levy assets.

These were what farmers have been saying all along. Under the farmers-backed measure, there would be a trust fund committee, under the Office of the President, that would manage the funds.

But even under the vetoed bill, executive branch officials were listed as members of the PCA board. These include the secretaries of Science and Technology (DOST), Trade and Industry (DTI), Agriculture (DA), Finance (DOF), and Budget and Management (DBM).

- The composition of the PCA board puts taxpayers’ money in the hands of private individuals and the board will end up like the “corrupt-ridden” Road Board.

Farmers took offense at this because Malacañang is opposing the inclusion of civilian representatives, which, simply put, are farmers. They reminded Malacañang there would be no coco levy fund in the first place if these taxes were not stolen from them and their elders.

“They treated farmers as if they are part of the private sector, when, in fact, the money came from them,” said Katarungan secretary general Danny Carranza.

Duterte’s earlier opposition to the higher representation of “civilians” over government officials was already addressed. Despite this, Malacañang still vetoed the measure.

“The composition of the reconstituted 15-member PCA Board under the PCA bill includes 7 members coming from the private sector. A receipt of P10 billion by the board from taxpayers’ money therefore translates to permitting private persons to influence the disbursement of public funds,” said Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo.

Apparently they do not want farmers to help manage the funds at all.

One veto after another: Trust fund bill

A few days after the veto on the PCA reconstitution bill, the trust fund bill was next. It was something expected. After all, the trust fund bill would not prosper without a strengthened PCA board.

In rejecting the trust fund measure, Duterte cited the following reasons:

- The establishment of an effectively perpetual trust fund would violate Action 6, Section 29 of the 1987 Constitution.

This provision states that: “[All] money collected on any tax levied for a special purpose shall be treated as a special fund and paid out for such purpose only. If the purpose for which the special fund was created has been fulfilled or abandoned, the balance if any shall be transferred to the general fund of the Government.”

Farmers slammed this reason because it was clear in the bill that there was no perpetual trust fund. There was a 25-year limit imposed or until the funds run out.

“Hindi nagbasa ang Malacañang dahil nilagyan ng 25-year limit noong bicameral conference committee…. So hindi siya perpetual (Malacañang did not read the bill because there was a 25-year limit imposed during the bicameral conference committee. So it is not a perpetual trust fund),” Faustino said.

- The bill lacks a “limit on a covered land area for the entitlement to the benefits of the Trust Fund.”

This, said Duterte, might lead wealthy coconut farm owners to benefit “disproportionately” from the trust fund compared to the smallholder farmers who need the assistance more.

This was the point of farmer groups and advocates all along. In fact, under the farmers-backed proposal initially filed in Congress, there was a 5-hectare limit for farmer beneficiaries.

This was removed in the House version but was retained in the Senate version. However, the provision was removed in the bicam – prompting opposition Senator Risa Hontiveros to vote against its ratification.

“That’s what we’ve been saying all this time, there is a need for the 5-hectare and below limit. Why didn’t Malacañang say anything about it and now they are using it to veto the trust fund bill?” an exasperated Faustino said.

- “The broad powers given to the PCA undermine relevant regulations and safeguards that were established precisely to avoid abuses.”

Again, this was among the original proposals of farmers: the creation of a trust fund committee, directly under the President.

“Exactly what the sector had been saying, that there is a need for a trust fund committee for the coconut levy. That was included in the first proposal. Why didn’t Malacañang say anything amid long debates and discussions on the bill? If they really want it, there are ways to do it. But if they don’t, they’ll find excuses,” Faustino said.

“Naprito ang mga magniniyog sa sarili nilang mantika (They were fried in their own oil),” he said.

Executive to blame

Lawmakers have blamed the inefficiency of Presidential Legislative Liaison Office Secretary Adelino Sitoy for failing to communicate the gap between Congress and Malacañang.

Senate President Vicente Sotto III said there is a “need to revitalize or even upgrade the PLLO.”

“This is the nth time that we do not know what the executive department wants from us,” Sotto told reporters.

But for farmers, this could not just be all about Sitoy. After all, it was Duterte who made the promise in 2016. The PLLO is also under the Office of the President. Duterte had the power to inform lawmakers about what he wants in the bill. But that didn’t happen.

“Hindi na ‘yan puro PLLO (It’s not just PLLO). It was also his decision,” Faustino said.

With heartbreak after heartbreak, farmers are left with nothing but the desire to continue the journey. The fight for them goes on.

“Before, there was no discussion on the money, on the trust fund. Now, it’s the main contention. It’s still a forward movement even if we haven’t achieved it yet. I see no reason why the farmers should not keep on doing it, whoever sits, even if it’s Danding Cojuangco. The fight continues,” Faustino said.

These were the same farmers who marched 1,750 kilometers from Mindanao to Malacañang to demand the return of the fund. It opened a door for them but at the end of the day, it would all be about political will given influential groups.

For now, farmers are keen on making their voices heard come May 2019 elections by campaigning against senators and representatives who derail the measure. Whether or not this is effective remains to be seen.

But until a law is passed, coconut farmers continue to toil daily with a meager income while those who gained from the fund continue to enjoy the benefits. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.