SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE

- The Chinese government is fighting online gambling, but companies are moving its operations offshore to avoid sanctions.

- Real estate and other Philippine businesses are booming due to online gambling operations.

- The Philippines’ regulatory environment is weak, but government agencies are slowly trying to cover the gaping holes.

READ: PART 1| A Chinese online gambling worker’s plight in Manila

MANILA, Philippines – With a business degree from one of the Philippines’ top universities, Jake, not his real name, expected to apply what he learned in college.

He was hired as a financial analyst by an information technology (IT) firm in Quezon City, but his job was nothing like what he was promised by the hiring manager.

He was tasked to insert a USB drive or memory stick into a computer and input a code.

“I had no idea at first what I was doing, but it turns out, I was paying out money for online gambling winners,” Jake said.

He told Rappler he had no idea about the money flow or whether the funds came from – or were going through – Philippine financial institutions.

Other than inputing codes, he was also tasked to look for Chinese players to play games online. Either he contacted them directly or looked for players through affiliates who had connections with players in China.

Players came mostly from China, but there were also Chinese clients from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United States.

Jake said the company he was working for had around 200 employees with a fair mix of Filipino and Chinese employees.

“You do not need to speak Mandarin. Your output can be in English and somebody, either Chinese or Filipino fluent in Mandarin, will translate for you,” Jake said.

“Our job is marketing or finance and some IT. It was not explicit that it was online gambling, but it was,” he said.

The company did not provide any hint of gambling. The offices had no roulettes, no cards, no dealers. All the games were streamed abroad.

The website Jake was working for indicated that its casino dealers were from countries like Russia and Turkey.

We have a code, when we say something like ‘aja’ out loud, it means that there are government agents or police about to go in the office and we need to hide everything.

Jake, a Filipino who worked in an online gambling firm

He said the industry was giving Filipinos opportunities and paid well. On top of their salary, workers enjoyed bonuses of at least P500,000 (US$9,631)* a year.

“Bonuses are tax-free and I think all workers had P500,000 at minimum. I accidentally saw the salary of some of the Chinese managers and they earned over a million without the bonus,” Jake said.

He said the Chinese workers earned around P60,000 ($1,156) to P70,000 ($1,348) a month. Filipinos earned slightly lower, but definitely much higher than a typical job at call center companies just some floors below their offices.

Rappler was able to interview a Chinese worker from another company who earned much less than the rates Jake indicated. Wei (not his real name), who comes from a province in China, said they were promised $2,000 or over P100,000 by a recruiter, but when they got to Manila they received only half.

Jake said he does not know of a similar story in his company, but added that he did not ask whether the rates promised were actually the salaries of his co-workers.

“I think the pay is high, the Chinese workers earn much higher than the average call center agents,” Jake said.

While cash was good, he admitted that he knew the company he was working for was shady.

The Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGOs) are regulated by the Philippine Amusement Gaming Corporation (Pagcor), but Jake said his company was not on the list of accredited gaming companies.

“We have a code, when we say something like ‘aja’ out loud, it means that there are government agents or police about to go in the office and we need to hide everything,” Jake said.

“I’m sure the bosses have connections with government officials, otherwise the company will not operate and will have higher taxes, which they do not want if they wanted higher bonuses,” he added.

He also said the company’s websites have several backups, in case China’s firewall blocks them. When it does, the backup websites take over.

Jake left the company after a couple of months because he felt uncomfortable about its questionable and suspicious operations.

Sweet spot for gambling

Despite all of President Rodrigo Duterte’s tough talk against gambling, the Chinese have found their gaming haven in the Philippines. An expert said it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Alvin Camba, a PhD candidate at Johns Hopkins University working on the political economy of Chinese foreign capital, said the Philippines’ cheap real estate, booming service sector, and autonomy from China were the perfect conditions that ushered the rise of online gambling operations. (READ: How China’s online gambling addiction is reshaping Manila)

Moreover, Camba said offshore gambling does not threaten the local market. It does not threaten Philippine businesses and instead offers jobs. But what really hastened the rise of online gaming in the country was Duterte’s move against the Roberto Ongpin-majority owned Philweb, a publicly-listed company that provided services for gaming and internet business activities.

In 2016, Duterte promised he would “destroy” Ongpin. That remark eventually led to Ongpin’s resignation from the company. Ongpin owned over 53% of Philweb before he sold all of his shares for only P2 billion ($38.4 million).

Duterte’s remarks also led to Pagcor ending its 13-year contract with Philweb, thus allowing the sale of gaming licenses outside special economic zones. The Philweb contract essentially allowed it to enjoy a monopoly.

Philweb under Ongpin did not deal too much with Chinese firms because of the previous policies of former president Benigno Aquino III. Besides, Aquino was not a fan of China.

When the contract ended, Pagcor regained its powers to sell licenses and open up the market to offshore gambling firms, including Chinese online gaming companies.

Gambling operations

To operate, offshore gaming companies need to team up with either a foreign or Philippine-based operator. These operators provide the gaming companies with the platform and other services such as technical support and marketing.

These operators then have to secure from Pagcor a license that costs $120,000 or roughly around P7.8 million. Renewal of the license is done once every 3 years and costs $120,000 as well.

Companies also need to register and pay for their live play streaming provider ($120,000), accreditation of the local partner ($60,000), gaming provider ($120,000), and customer relations ($120,000), on top of other operation-related fees paid to Pagcor. To start operations, gaming firms each need to shell out a total of around $900,000 (P47 million).

Of the total gaming income, companies need to remit 2% to Pagcor as a regulatory fee. A third party audit system determines the gross earnings of license holders.

Philweb was the only gaming operator before the Duterte administration.

Jake said the company he worked for did not go through the scrutiny of Pagcor. He said the firm used an IT company as a front. Poker, roulette, sports betting, and other games are all done in other countries like Turkey and Russia.

The company is “technically” an IT firm or can even be considered as a call center. Because it handles customer support and does programming, it hides the fact that it is part of the gambling ecosystem.

There are currently 56 Pagcor-approved online gambling operators in the Philippines, but there may be more that are unregistered, which means that they are able to evade taxes.

Pagcor is explicit that any operation related to online gambling needs a license. However, the blurry lines and the transnational nature of the overall operations provide enough of a smokescreen for gambling companies to avoid paying taxes.

“Just go to a high-rise office and look at the directory on the wall. If it has words related to Chinese culture, it probably is a gambling company. Or just take a look at the volume of Chinese in the area, they are probably in gambling,” he said.

The booming industry also has questionable working conditions for those brought in from China, and raises issues pertaining to Philippine immigration laws.

For instance, workers enter as tourists in the Philippines, with some processing employment requirements, or completely doing away with them. In 2018, over 1.2 million Chinese tourists entered the Philippines, second only to South Korea’s 1.6 million tourists. Some of these tourists end up in the online gambling industry.

Government pushes back

The Department of Finance (DOF) estimated that the government lost some P32 billion in uncollected income taxes from about 140,000 foreign workers in online gambling.

To resolve this, its attached agency, the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) issued Memorandum Order No. 28-2019, requiring foreigners to secure a tax identification number first before being allowed to work in the country.

Foreigners should also register with revenue district offices (RDOs) that have jurisdiction over the physical address of their employers.

Other foreign workers who already have working visas or have alien employment permits issued by the Bureau of Immigration (BI) are also required to register with the RDOs.

An inter-agency task force composed of the DOF, BI, Pagcor, Department of Labor and Employment, National Bureau of Investigation, and Department of Justice keeps tabs on online gaming firms.

Illegal Chinese workers have been arrested, according to news reports, but Jake said this may also be due to competing companies squealing on them.

“The industry is getting competitive, so some companies actually report other fellow gambling companies,” Jake said.

Pagcor profits

Pagcor has not yet revealed how much POGOs earn or how big the industry is in the country. However, Pagcor’s income spike gives a sneak peek into how online gambling is helping the agency surpass its targets.

In January to April in 2019, Pagcor posted an 11.4% revenue growth as its gross earnings reached P25.09 billion. This amount is P2.57 billion more than the P22.51-billion revenues recorded in the first 4 months of 2018.

The agency surpassed its P23.57-billion target for the period in review by 6.45% or over P1.5 billion.

A bulk of it, or P23.84 billion, came from POGO fees.

During the entire 2018, income from gaming operations (including online and traditional physical casinos) stood at P67.9 billion, 18.5% higher than 2017’s P57.3 billion.

Loopholes

Another concern of market observers is the possibility of gambling firms being used as a means to launder money.

Lucio Pitlo, an expert on Chinese studies, said that the Philippines’ bank secrecy laws, which make it hard for governments to open up accounts, could be exploited by money launderers.

“Online gambling is very shady – to what extent it uses financial intermediaries, where does the money go and come from, nobody knows, or the government kasi matipid ang sinasabi [says very little],” he said.

Much of the discussions in Congress have focused on the rise of illegal foreign workers. It was only detained Senator Leila de Lima who proposed probing into the gambling frenzy in Manila. That Senate investigation has not prospered so far.

Pagcor rules prohibit Filipinos from gambling online. But Rappler was able to access several online gambling websites run by the Chinese.

While the Philippine government has started to cover the gaps in the growing online gambling industry, there have been no moves at all to completely eradicate the business. Regulating it has also proven to be quite tricky.

Duterte considers China his “friend,” yet has not signaled anything so far to put an end to online gambling.

Pitlo said China “absolutely hates” gambling.

“China is very image-conscious, and if they had it their way, they would stop it. But China knows it cannot impose anything because the Philippines is independent [of it],” Pitlo said.

Since the 1950s, gambling has been forbidden in China, as it is regarded as being connected to prostitution and drugs. Beijing has allowed only state-run lotteries.

China has cracked down on online gambling and players, and even banned the word “gambling” in its social media and online search websites.

However, gaming firms have found creative ways to skirt these rules.

Gambling, or “bocai” “xinyun bocai” in Mandarin, cannot be found in search engines. However, Jake said their website can be found when a user types “bo cai” or spinach. He said the similarity of the two words is a loophole that gambling firms have exploited.

Apart from the Philippines’ independence, local interests also protect the industry from crackdowns.

Booming businesses

Several sectors are raking in the benefits of having online gambling operations in the Philippines.

Camba said gambling may have saved the real estate industry. While the industry bubble did not pop, he said online gambling took up substantial office space, averting a possible glut.

Around 2004, real estate companies started constructing tall office buildings for the BPO industry, in anticipation of the growth and expansion of BPOs.

However, industry experts did not anticipate that the BPO industry would mature at such a fast pace. When the buildings were completed sometime 2015 and 2016, there were already vacancies in office spaces being noticed.

In 2016, when US President Donald Trump was elected, BPOs became wary about investing overseas due to the conservative leader’s protectionist policies.

But thanks to online gambling, the local real estate industry is bathing in cash.

Latest data from property consultancy firm Pronove Tai shows that during the 1st quarter of 2019, POGO office demand recorded a 118% growth year-on-year.

“POGOs’ leasing behavior has evolved into preleasing (leasing before the building has been completed) to match their requirements,” Pronove Tai said.

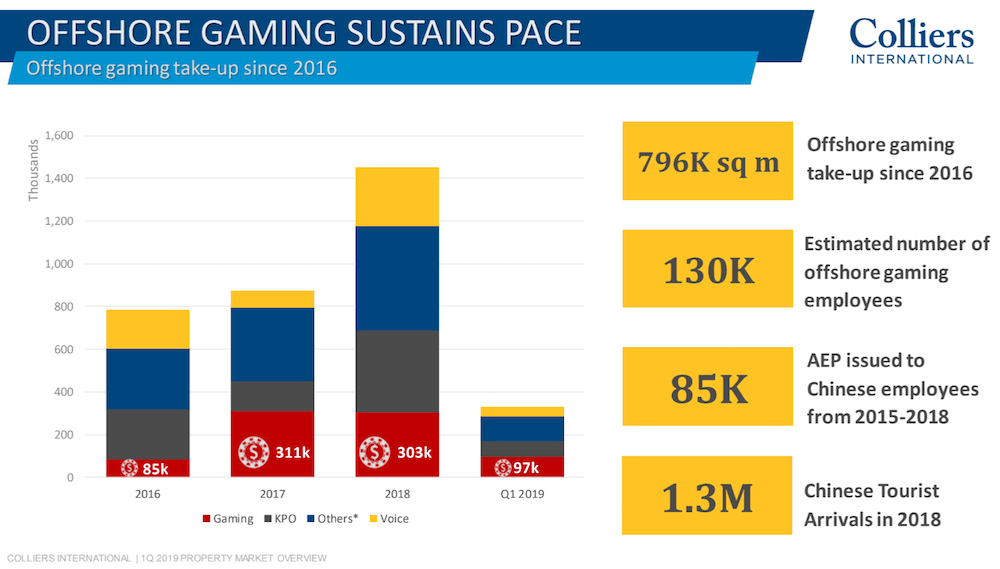

Meanwhile, properties consultancy firm Colliers International noted that POGOs have taken up a total of 796,000 sqm of office space since Duterte started his presidency in 2016. This represents a 256% leap from just 85,000 sqm in 2016 to 303,000 sqm in 2018.

Moreover, the take up in the 1st quarter of 2019 already reached 97,000 sqm, 14% higher than the entire year of 2016.

The figures indicate that the Philippines may reach a million square meters of office space dedicated just to offshore gambling in 2019.

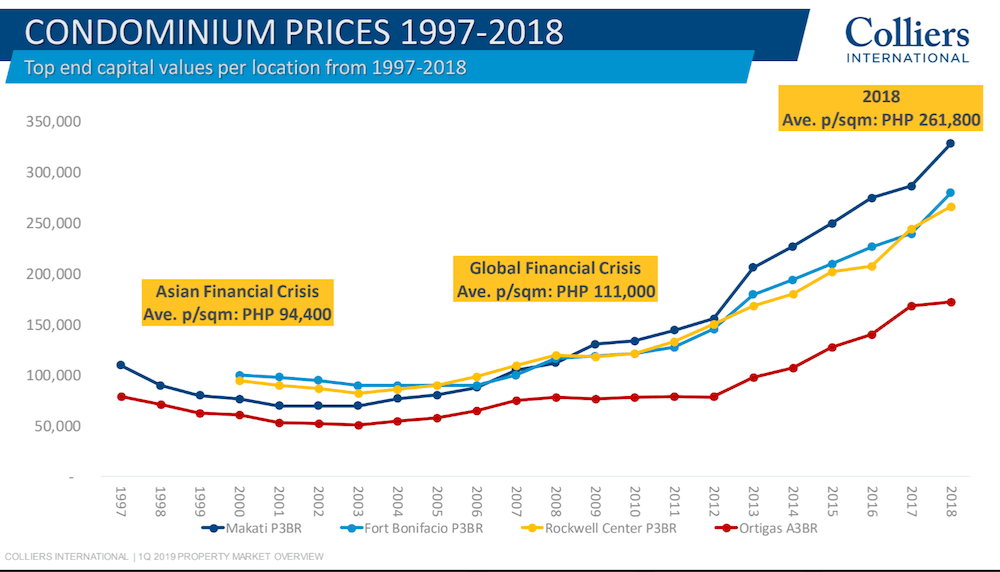

Condominiums also gained more cash. As of 2018, average condominium prices in Makati already soared to as high as P261,800 per sqm, more than double the prices just over a decade ago.

This consistent rise of condominium prices also pushed up the rental rates, much to the disappointment of local residents.

The food industry also found a new market to cater to. Some restaurants near gambling operations have even modified their menus to fit the preferences of the Chinese.

Untangling China

The rise of online gambling in the Philippines is something that Filipinos struggle to make sense of.

While real estate and some Filipinos getting jobs are the clear winners, the costs and possible adverse effects of having a growing industry notorious for being linked to criminal activities have yet to be determined. The government has started to put a tighter leash on firms, but wily businessmen are already several steps ahead.

Gambling firms are illegal in China, yet they have found a creative way to still cater to mainlanders and have sought legal fronts in other countries that allow online gambling.

But even as countries like the Philippines have laws and regulations covering the industry, it seems that Chinese gambling firms still have an ace up their sleeve, eyeing expansion and more wins.

To further complicate the picture, the rise of online gambling comes at a time when the Philippines and China play tug-of-war over disputed waters. China is also expanding its political power by investing in other countries – including the Philippines – through assistance and low-interest loans. (READ: Made in China: Loans with waivers, shrouded in secrecy)

Online gambling, the influx of Chinese workers, the bitter dispute over the West Philippine Sea, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative are different, yet interconnected issues altogether. These intertwined narratives may take some time to untangle. – Rappler.com

*US$1 = P51.91

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.