SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE

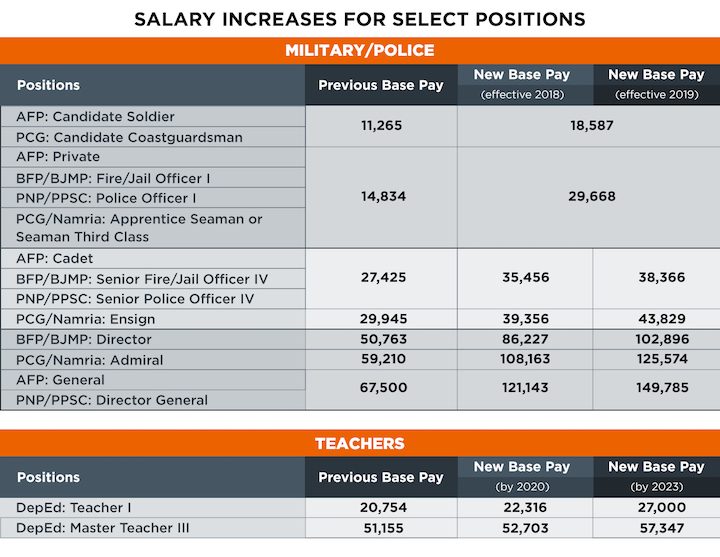

- Teachers and government workers will be receiving new salary hikes starting 2020, but not as much as what was provided to the military and the police in 2018.

- The government has also spent more for the salary hikes for uniformed personnel than for civilian employees, at least in the first tranches of the salary hikes.

- With nearly a million teachers nationwide, a salary increase will entail big sums of money

MANILA, Philippines (UPDATED) – After waiting for a salary increase that President Rodrigo Duterte promised as early as July 2016, Filipino teachers are finally getting their pay hikes starting 2020. Yet it seems they will still be no better off than the police and soldiers in uniform, whom the Duterte administration chose to prioritize.

In 2018, uniformed personnel saw their pay increase by 50% to 100%. Teachers, on the other hand, will see their salaries improve by only a little over P6,000 spread across 4 years, depending on their salary grade levels.

The salary increases in the proposed update to the Salary Standardization Law (SSL) will take effect from January 1, 2020, after the President signed on January 9 the bill that would authorize the release of the pay hikes. Duterte signed the budget bill itself – which includes the allocation for the salary increases – only on Monday, January 6.

The SSL dictates the salaries of the entire government bureaucracy. This is why, in his 4th State of the Nation Address in July 2019, Duterte said the pay hike will cover not just teachers, but the rest of the government workforce, too.

Comparison in pay

The last SSL update – implemented via Executive Order No. 201 in 2016 – expired in 2019. In that SSL, teacher positions ranged from Teacher I to Master Teacher IV with varying salary grade levels (see table). As of writing, there is no one hired or promoted to Master Teacher IV yet, according to the Department of Education (DepEd).

In December 2019, the House of Representatives and the Senate passed new measures – House Bill 5712 and Senate Bill 1219 – which sought to distribute the increases for all government workers in 4 installments over a period of 4 years (2020 to 2023).

| Position / Salary Grade | 2019 (last SSL) |

2020 (1st tranche) |

2021 (2nd tranche) |

2022 (3rd tranche) |

2023 (4th tranche) |

| Teacher I Salary Grade 11 |

20,754 | 22,316 | 23,877 | 25,439 | 27,000 |

| Teacher II Salary Grade 12 |

22,938 | 24,495 | 26,052 | 27,608 | 29,165 |

| Teacher III Salary Grade 13 |

25,232 | 26,754 | 28,276 | 29,798 | 31,320 |

| Master Teacher I Salary Grade 18 |

40,637 | 42,159 | 43,681 | 45,203 | 46,725 |

| Master Teacher II Salary Grade 19 |

45,269 | 46,791 | 48,313 | 49,835 | 51,357 |

| Master Teacher III Salary Grade 20 |

51,155 | 52,703 | 54,251 | 55,799 | 57,347 |

| Master Teacher IV Salary Grade 21 |

57,805 | 59,353 | 60,901 | 62,449 | 63,997 |

* Note on table: Amounts in pesos. Step 1 amounts only.

Employees in SG 11 like Teacher I, for instance, are supposed to receive P22,316 per month in 2020, or an increase of P1,562 from 2019. They will eventually get P27,000 by 2023, or an increase of P6,246 from their 2019 pay.

While the SSL update benefits more government employees, its proposed increases will hardly be felt.

ACT Teachers party list Representative France Castro told Rappler that the salary increases were “hindi sapat (not enough),” and the substantial salary increase long sought by teachers “was not considered.” She also said it “did not address discrimination in the salary scale of government employees.”

In comparison, military and uniformed personnel (MUP) saw on average a 58.7% increase in their pay across ranks in 2018 compared to 2017, according to the Department of Budget and Management (DBM), thanks to Joint Resolution No. 1 signed in 2018.

Many entry-level personnel in uniform benefited the most in the first tranche, with a 100% hike. By the 2nd tranche in 2019, those in the topmost ranks had also seen their salaries doubled.

At around the time the salary hikes for the military and police were granted, Mindanao was under martial law, the government was in the middle of its “war on drugs” campaign, and tensions over maritime claims continued in the West Philippine Sea.

Bigger spending for MUPs, too

As a consequence, the government also spent big to fulfill its promise to the military and the police.

At the time the MUP pay increase was being deliberated on, the DBM estimated it would cost P64.2 billion in fiscal year 2018. But the DBM’s 2020 National Expenditure Program – which has summaries of actual and planned spending from 2018 to 2020 – indicated that around P68 billion was actually transferred in 2018 from the Miscellaneous Personnel Benefits Fund (MPBF) to the 10 MUP agencies supposed to get the salary increases.

The MPBF is a lump sum fund that covers authorized salary adjustments, benefits, and allowances of government employees.

After 2018, the funds for MUP salary increases were sourced from the respective budgets of the 10 agencies. In the 2019 budget for the Armed Forces of the Philippines under the Department of National Defense, the base pay for soldiers amounted to a total of P56.29 billion, which already factored in their new salaries.

Meanwhile, the government said it had earmarked only P31.1 billion for the first tranche of salary increases in 2020 under the new SSL. This is supposed to be sourced first from the MPBF in 2020, then from the agencies’ budgets in subsequent years.

Castro earlier told Rappler this earmarked amount was not enough. “That P31 billion, kapos iyon (that would fall short) if we really want a substantial salary increase,” she said in a mix of English and Filipino. She even pointed out that in 2016, the allocation for the first tranche of the SSL already amounted to P57.9 billion, benefitting more those in the higher salary grade levels and minimally increasing the pay of those in the lower salary grade levels.

In the first installment of the old SSL in 2016, the increases from 2015 across salary grades ranged from P478 (for SG 1) to P40,924 (for SG 33).

By comparison, the first installment of the new SSL in 2020 will see increases from 2019 ranging from a low of P483 (for SG 1) to only P7,762 (for SG 33).

Because no computations were readily available, Rappler computed the cost of salary increases for teachers covered by the P31 billion allotment in the 2020 budget. Based on estimates, the increases for teachers will cost the government only a maximum of around P19 billion for the first tranche. If only filled teacher positions as of June 2019 are considered, the pay hikes would cost around P18 billion. (See note on methodology below.)

| Position / Salary Grade | Increase in 1st tranche (in pesos) |

Authorized positions (as of June 2019) |

Increase for the year (product x 14 months) |

| Teacher I Salary Grade 11 |

1,562 | 468,453 | 10,244,130,204 |

| Teacher II Salary Grade 12 |

1,557 | 139,487 | 3,040,537,626 |

| Teacher III Salary Grade 13 |

1,522 | 212,384 | 4,525,478,272 |

| Master Teacher I Salary Grade 18 |

1,522 | 41,854 | 891,825,032 |

| Master Teacher II Salary Grade 19 |

1,522 | 16,810 | 358,187,480 |

| Master Teacher III Salary Grade 20 |

1,548 | 68 | 1,473,696 |

| TOTAL ESTIMATED COST OF INCREASE (1st tranche) | 19,061,632,310 | ||

The P19-billion estimate is even lower than the annual cost of the proposals for teachers’ salary increases, as outlined in at least 63 bills filed in the Senate and in the House in the 18th Congress. Salary increases in these bills ranged from a low of P49 billion to a high of P456 billion a year.

These proposals had different versions, scopes, and funding sources. The bills pushed for either another salary grade upgrade, an across-the-board addition to the base pay of teachers, or sought to fix their minimum monthly base pay.

Considerations

With nearly a million teachers nationwide, a salary increase would already entail big sums of money, said DepEd Undersecretary Annalyn Sevilla. A mere P10,000 increase in salary for teachers alone would already cost the government around P140 billion-P150 billion, Sevilla explained.

Sevilla cited 3 possible means to cover this huge expense, all of which are quite difficult to pull off: raising taxes, borrowing money through loans, or reallocating from other items in the national budget.

Other benefits that use the salary as basis – overtime pay, retirement pay, terminal leave, honoraria, and teaching overload pay – would also increase.

This is why DepEd has said that while it supports higher pay for teachers, any proposal should be “equitable, within [the government’s] means, and sustainable.” Sevilla added that the DepEd has helped teachers through other means, and supported proposals like the creation of new teaching positions from Teacher IV to Teacher VII.

Sevilla also said, “The Secretary [Leonor Briones] is saying, let’s think about the holistic approach. Sana lahat, standard ang increase (Hopefully all will get a standard increase), which will happen in 2020″ in the proposed national budget.

Former budget secretary Benjamin Diokno also initially had qualms about increasing salaries in government. In the case of teachers, Diokno argued in January 2018 that providing pay hikes for them would cost an additional P343.7 billion under Personnel Services spending. This, in turn, “will increase our deficit to 5%, which will make the public sector deficit unmanageable.”

Diokno also opposed at first the proposal to double the salaries of uniformed personnel, saying it will “take a lot of time and consideration.” But he was eventually overruled.

Asked why the government was able to provide the pay hike to uniformed personnel first, Sevilla explained that their pay scales had not been adjusted for a longer time. Before Joint Resolution No. 1 in 2018, the MUPs’ salaries were laid out in Joint Resolution No. 4 signed in 2009. (Sevilla previously worked with DBM as a senior budget and management specialist.)

In the 2016 SSL, they were only given provisional and officers’ allowances, along with an increase in hazard pay. “Civilian personnel every year have a salary increase [through SSL]. Uniformed personnel don’t…and for so long, [their pay scale] has been neglected,” she said in a mix of Filipino and English.

Sevilla added that there are fewer MUPs than teachers, and highlighted the greater risks the military and the police are facing while on duty.

Representative Castro, however, said that whatever the cost to fund substantial salary increases for teachers, the government can do it by reallocating some funds, like the intelligence funds of the Office of the President and other agencies, as well as the Special Purpose Fund. Tax and tariff collections could also be improved and made more efficient.

“It’s feasible if they want it…It’s just political will, like what they did for uniformed personnel,” she said. – Rappler.com

Methodology: To compute for the estimated cost of teachers’ salary hike proposals in the 18th Congress, Rappler used the authorized number of positions for Teacher I to III and Master Teacher I to III only, as of June 2019, based on DepEd data. To get the annual increase in pay, the monthly increase (based on the 2016 SSL) was multiplied by 14, or 12 calendar months plus the midyear and Christmas bonuses.

For bills seeking to upgrade teachers’ salary grades (SG), the same movement from SG 11 to the proposed SG was applied to the higher salary grades. For bills seeking across-the-board increases, the proposed amounts were added to the salaries corresponding to the concerned SG levels. For bills that fixed salaries to a certain amount, the difference of the proposed amount and the pay for those in SG 11 was added equally to the other SGs.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.