SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

READ: Part 1| Bilibid returnees die in Duterte administration blunders

AT A GLANCE

- Ex-prisoners voluntarily surrender in good faith out of fear of the President’s shoot-to-kill order.

- The Correctional Institution for Women reportedly accepted surrenderers “without checking” if they were covered by the President’s orders.

- Bottlenecks among higher authorities delay the processing of clearances for the returnees’ release.

- There are no guarantees for returnees who may want to exact accountability from authorities who caused their unjust, prolonged detention.

MANILA, Philippines (UPDATED) – “Payagan mo na ako, ate. Natatakot ako sa kung anong baka mangyari sa ‘kin,” Tinay* told her sister. (Let me go. I’m afraid of what could happen to me if I don’t go.)

“Hindi mo naman kailangang pumunta doon. Hindi ka naman kasama doon sa heinous crimes. Baka hindi ka na makauwi,” her sister replied. (You don’t need to go. You didn’t commit a heinous crime. You might not be able to go back home.)

None of Tinay’s family was able to convince her to stay. The President’s words were firm and terrifying: any former prisoner refusing to surrender would be considered a fugitive, wanted dead or alive. The police were instructed to pursue them on a shoot-to-kill basis if they didn’t come after the 15-day period.

Tinay, a parole grantee of the Correctional Institution for Women (CIW) for qualified theft, knew that President Rodrigo Duterte only ordered on September 4 that the almost 2,000 released heinous crime convicts surrender and have their Good Conduct Time Allowance (GCTA) recomputed. Qualified theft is not a heinous crime.

However, a Facebook post from the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor) convinced Tinay to return. Just like Duterte’s order, the post instructed heinous crime convicts released by the GCTA law, or Republic Act 10592 to surrender. Apart from these, the post also specified escapees, habitual delinquents, and recidivists who benefitted from GCTA. Tinay claimed to be none of these.

“Nauna kasi ‘yung takot ko (My fear came first),” she told Rappler.

Four days after Duterte gave the order, she and an acquaintance also serving parole turned themselves in to the CIW.

Not a heinous crime convict yet detained

In 2005, Tinay ran away from a family conflict in her Manila home and sought a friend in a province in the north. She was detained there after committing qualified theft, and moved to CIW in Mandaluyong 4 years later. Tinay was away from home for a total of 10 years before being granted parole in 2015.

Freed, in her 30s, and with a whole life ahead of her, Tinay was just happy to be home to spend time with her parents and her best friend of an older sister. Tinay realized how her parents had aged when she came home, and she promised herself she would be a good daughter following her long years of absence.

She traveled to CIW with her discharge form, a document given to persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) upon release. It certifies her release and parole grant. It was the only thing she brought with her, as she thought securing a clearance would be quick.

Tinay was given a waiver that she hesitated to sign. She asked what it was for. It’s just a formality of your surrender, they told her.

“Nagdadalawang-isip kasi ako eh. Baka may ibang meaning ‘yung waiver na yun. Baka yung waiver na ‘yun ay ikakapahamak ko. Pero hindi talaga ako makahindi kasi nandoon sa harap ko ‘yung mga empleyado. Walang nag-explain kung ano yung pinipirmahan ko,” she said.

(I was having second thoughts about it. The waiver might have had a different meaning. It might cause me even more trouble. But I couldn’t say no because the prison employees were right in front of me. No one explained what I was signing.)

As Tinay was among the first to turn themselves in for GCTA recomputation, there had been no detention center for returnees yet. After waiting in an informal holding room, she was brought later that day to the same facility that houses minimum-security inmates.

They asked her to spend the night, notwithstanding her protest.

“Doon ako nagreklamo sa empleyado na nag-interview sa akin. Sabi niya, utos daw kasi ng Presidente. Wala daw silang magagawa, kasi utos ng Presidente,” she said. (That’s when I complained to the employee who interviewed me. They said, it’s the President’s orders. They can’t do anything, because it’s the President’s orders.)

President Duterte promised not to send returnees back to prison if they “surrender in good faith” because “there was really a release order.”

Returned to secure clearance, never let out again

Ging* and Xandra* weren’t able to say goodbye to their family in Bulacan. They were just intending to report and secure a clearance. It was an errand.

The couple, who met when they were PDLs together in CIW way back in 2011, chose to live their post-prison lives with each other. Not without a few breakups in between, they knew they wanted their relationship to last when they moved in together with their families.

After hearing Duterte’s order, they reached out to a former CIW employee about what they should do. They were advised to just go back “para malinawan (to seek clarification).” Better safe than hunted down as fugitives.

Ging was released through GCTA on her charge of qualified theft. Xandra’s case was drug use, where she completed her sentence without GCTA.

They told co-workers at their family business that they would go to the prison just to report. Ging’s job was just enough to support her teen daughter, who still had to work after school to support herself. With Ging gone, her daughter had to be financially self-reliant.

Ging was looking to provide more for her child as she had been applying to work abroad. She worried she wouldn’t be able to leave the country without an OK from the Department of Justice (DOJ), making her “surrender” even more urgent.

CIW was a 4-hour trip from their provincial home, with the women needing to shell out P500 for the travel expenses. The receiving staff asked them a few questions: where they lived, and what crime and sentence they served with the CIW before. They signed the same waiver that Tinay signed.

The couple was able to bring with them a few pairs of underwear just in case, but all the clothes they had were the ones on their backs. They were each given a toothbrush, a blanket, a mosquito net, a small towel, and a bar of soap – not a good sign.

They understood they would have to stay.

No doctors, medicines also out of stock

Tinay, Ging, and Xandra saw the number of returnees reach 76 in October. The minimum security inmates were transferred to where the higher-security inmates were, but even then, the beds weren’t enough for the returnees. Some women had to sleep on the floor.

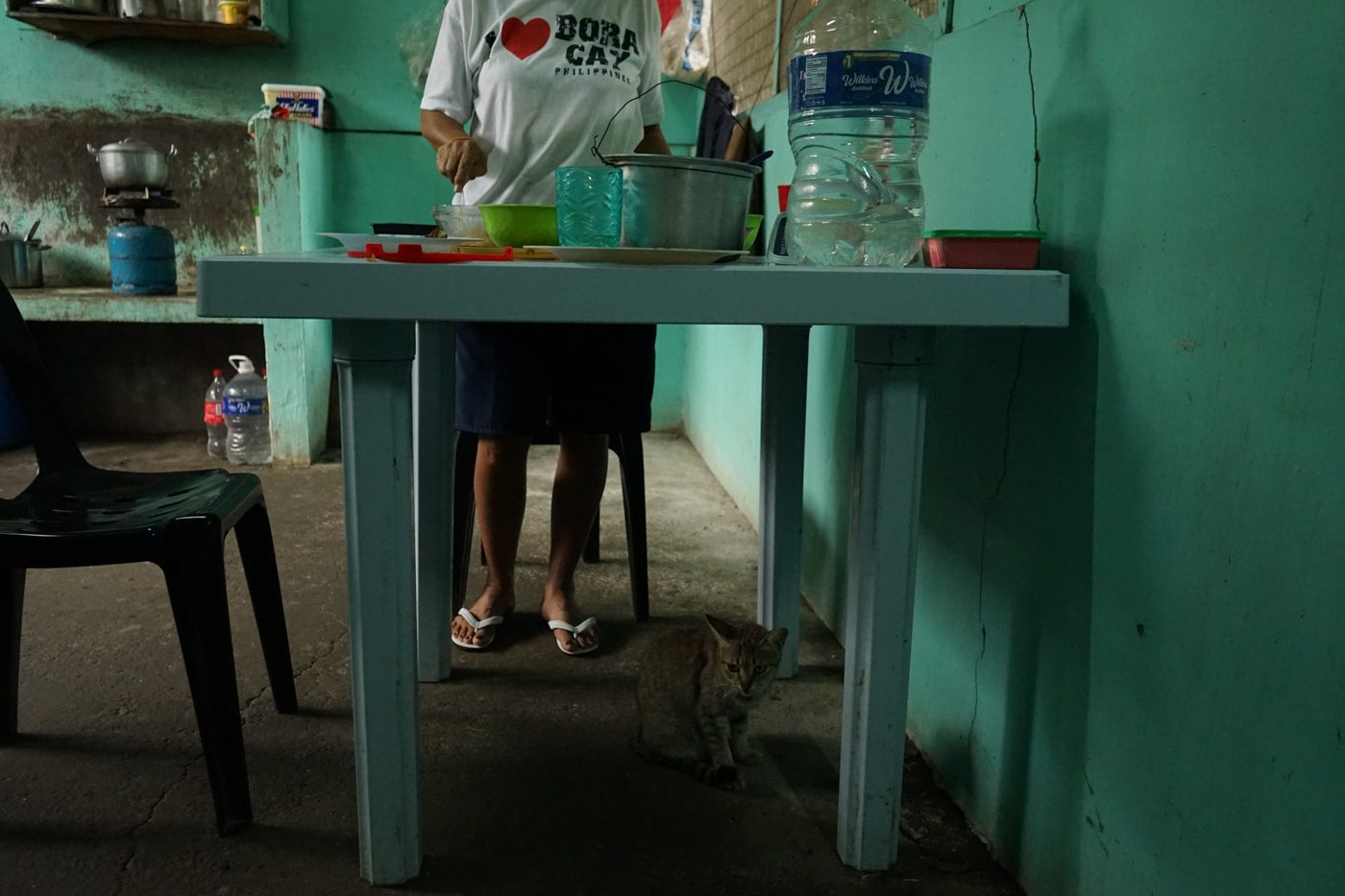

Since the returnees are not PDLs, there are no organized programs or activities set for them. They have a few things to entertain them, like a 12-inch television and some books and magazines. They pray at a makeshift altar from time to time.

Some women have found ways to earn money among themselves. Ging does the laundry for her fellow returnees for a small fee. Others do manicures and thread eyebrows. Tinay, who is restricted by a medical condition, can’t work. All she could do is watch TV and wait.

Prior to her return, Tinay was scheduled for a hospital check-up for uterine bleeding. Her sister came to bring her to the hospital, but CIW refused to release Tinay without an official request or court order.

“May bumaba dito na nurse at tinurukan ako tatlong beses ng tranexamic acid. Tinurukan ako nang hindi pa alam kung ano ba talagang sakit ko. Kinaumagahan, tinanggal na nila ‘yung pinang-inject sa ‘kin. Tapos nilagnat ako ng isang buong araw,” she said.

[A nurse came down here and injected me thrice with tranexamic acid (medicine that stops bleeding). They injected me without diagnosing the problem. The next morning, they removed the IV, and I had a fever the whole day.]

The returnees also reported that two children came with their mother when she surrendered to the CIW. The children stayed with her inside the holding area.

The mother would become hysterical as her child was getting sick, and the CIW had no on-site doctor to attend to them. Ging said that even during the time she was serving her sentence, she would only see doctors come during medical missions. Medicines were also reportedly often out of stock.

Ex-superintendent Marasigan

When they would ask then-superintendent May Ann Marasigan when they would be able to go home, Marasigan would reportedly only tell them they’re fine at the facility, and that they were being fed.

As the returnees approached two months in detention, an employee entered their holding area with a list of women who were approved for release. The women gathered around, anxiously waiting for good news.

One by one, the prison staff read the names out loud. Twenty-seven names were called that day.

To Tinay’s utter dismay, her acquaintance on parole was called for release. Tinay wasn’t called, and neither was Ging or Xandra. Tinay was one of the first to come forward to “surrender,” not even a heinous crime convict or GCTA beneficiary, and 27 were released before her, including the person she came with.

Tinay cried in a panic. She chucked her cellphone at a wall, which Xandra caught at the right moment. “Heto, magagamit mo pa (Here, you can still use this),” Xandra said in jest as she handed the phone back.

“’Wag ka na magalit. Makakauwi din tayo. Siguro siya lang ‘yung nauna,” Xandra said as she calmed Tinay down. (Don’t be angry. We’ll go home, too. Maybe she just happened to be first.)

Rappler has not been able to reach Marasigan for comment, who is reported to have left for Leyte following her removal as CIW acting superintendent. We will update this story once we are able to reach her for comment.

On November 11, she was succeeded by Angelina Bautista, a retired Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) officer.

“We are facilitating their immediate release because some have started to become depressed. We are actually in the midst of an investigation of the previous administration because the marching order of our President is clear: The only ones being called to surrender are heinous crime convicts who benefitted from GCTA,” Bautista told Rappler.

“So siyempre, kung pinadalhan ka ng letter, magsu-surrender ka. Ganoon ang nangyari. It’s the lapses of the previous administration, na supposed to be, hindi naman dapat nandito ‘yung mga returnees,” she said.

[So of course, if you receive a letter (to surrender), you would surrender. That’s exactly what happened. It’s the lapses of the previous administration – the returnees are not supposed to be here.]

Their extended stay, she said, is due to the previous administration sending their case files to the DOJ for GCTA recomputation. This mixed up cases of those who are and aren’t actually supposed to be subject to recomputation.

Only some of the women detained at the CIW received letters to surrender. The others simply returned out of fear. A few were hunted for arrest and brought to the prison.

A September 5 BuCor letter addressed to all superintendents of BuCor Operating Prison and Penal Farms (OPPFs) instructs them to establish temporary holding areas for returnees, vaguely describing the President’s order for the surrender of “all the 1,914 PDL who were released through the granting of RA 10592.”

The letter does not explicitly say that the 1,914 PDL referred only to the heinous crime convicts who were released under GCTA – different from Duterte’s order and the BuCor Facebook post.

Mistakes, errors

On September 12, BuCor acknowledged the 1,914 list as “rushed” and “unchecked.”

CIW documents officer Eleanor Vengco told Rappler that they were never furnished the list of 1,914, nor an official list of expected returnees for CIW.

Bautista said the CIW under Marasigan sent out letters “without checking” if the former-inmate recipients were actually GCTA beneficiaries. She said the letters sent out were based on the master list of names released from CIW, from 2014 onwards – the time frame Duterte specified.

A sample letter obtained by Rappler bears the name of a woman not included in the list of 1,914.

They also accepted women who turned themselves in even if they did not receive a letter, as in the cases of Tinay, Ging, and Xandra.

However, Vengco, who was around when Marasigan accepted returnees, said that in certain cases when a surrenderer came, Marasigan would consult with the DOJ on whether or not to accept her.

Of the 76 women who surrendered to the CIW, only 3 were found to be among the 1,914 names covered by Duterte’s order. When asked how come the 73 being detained were not heinous crime convicts, Vengco was unable to provide an answer, saying that only Marasigan might be able to explain.

Curiously one of the 3 who was listed as a murder convict was released again. Ging said this one may have been released because of humanitarian reasons, but the CIW was unable to confirm this, as details of the DOJ evaluations per returnee are not included in correspondence, according to Vengco. As long as the DOJ includes their name, they are cleared for release.

This brings into question an October 14 letter from BuCor addressed to Marasigan, which the CIW provided Rappler. On October 14, the DOJ Oversight Committee cleared 45 of the 58 returnees at the time, tasking CIW to issue their discharge forms. On October 31, however, only 27 of the 45 were released.

Bautista was unable to explain this. She said the only document pertaining to the returnees and which was turned over by Marasigan was the list of those who remained at the facility.

“Ayaw ko magsisi ng tao. Pero kita mo naman ‘di ba?” said Bautista. (I don’t want to point fingers. But you can see, right?)

Bautista disclosed that there is an ongoing investigation of Marasigan’s administration, following allegations of corruption, among other problems. She said the issue of accepting returnees not covered by Duterte’s order was the “last straw.”

When Bautista was newly appointed, she came to the returnees’ holding area and spoke words of encouragement. The women felt a new sense of hope. Bautista told them that she would see to it that they would be released as soon as possible.

Bautista has been in office for more than a month, and the returnees’ faith has started to fade.

“Ganon naman lagi sinasabi sa ‘min, na makakauwi rin kami. Pero puro pag-asa na lang. Paasa,” said Ging. (They always tell us that we’ll go home soon. But they always just give us hope. False hope.)

Going home

Since hitting the number of 76 returnees, women have been released in batches. The first was the largest, with 27 going home by the end of October. The next batch consisted of 3, followed by another 3, then 7, and most recently, one, who went home on December 10. About 35 remain inside CIW as of writing.

Ging and many women still inside share resentment that a good number of those who went home first were the ones who returned or surrendered later than they did. It was never clear to anyone at the CIW how some clearances are processed faster than others.

On November 7, Xandra was called to receive documents at the office. Ging was left at their facility, wondering what it meant. It was from the prison staff she learned that Xandra was cleared to go home.

“Sabi sa ‘kin ni Xandra pagbalik niya, ‘Mahal, uuwi na ako!’ Naging masaya kami na malungkot, kasi gusto rin niyang magsabay na kaming uuwi,” said Ging. (Xandra told me when she got back, “Love, I’m going home!” We were both happy and sad, because she wanted us to go home together.)

Even while dealing with Xandra gone, Ging never thought about escaping. She would rather leave, secure with the knowledge that she could no longer be rearrested. “Eh mamaya barilin nila ako doon sa labas eh,” she said. (They might just shoot me outside.)

On December 15, Xandra told Rappler that the family business she and Ging worked on is on the verge of bankruptcy, mainly due to their absence. Now she and Ging’s daughter have to leave their apartment too, because Xandra can’t afford rent on her own.

Tinay was finally released after 3 months of detention. Her employer at her housekeeping job, however, fired her due to her long absence. On December 16, her father was diagnosed with blood cancer. Jobless, desperate, and regretful, Tinay laments how she could have had more to keep her father alive if only she wasn’t detained for a surrender order she was never supposed to be part of.

The women inside wait with uncertainty every day. Bautista said that if it were only up to her, she would easily release those not included in Duterte’s order. But even releasing the women who were not covered by the GCTA order isn’t simple.

Up to the DOJ?

Since their case files were forwarded to the DOJ upon surrender, Bautista said the DOJ could question CIW for anomalies in releasing them without their green light.

On December 9, Bautista and BuCor Director General Gerald Bantag pointed at bottlenecks at the level of the DOJ Oversight Committee. “Pareho lang ang BuCor sa CIW (BuCor is in the same position as CIW),” Bantag said, after Bautista told Rappler all they could do was wait for the DOJ’s clearance to release those still in prison.

The DOJ, however, told Rappler on December 13 that they transferred evaluation and release authority to BuCor at around end-November. The DOJ, while processing names for release, was also training BuCor personnel on applying the new implementing rules and regulations of the GCTA law. This was done because DOJ thought BuCor may be in a position to do the work faster, citing technological capabilities.

“Once we were confident enough that the BuCor personnel were well-equipped in handling the releases, we passed the task of releasing the surrenderers to them. So right now, the DOJ no longer confirms their release. Only BuCor does entirely,” said DOJ deputy spokesperson Neal Bainto.

Lost jobs, time, opportunities

Bautista reported that there are 3 lawyers helping fast-track the documents, especially those who are not part of the surrender order. There is no lawyer, however, helping them on the aspect of prolonged detention.

Returnees have lost jobs, opportunities, and time with their families after completing their sentences or being granted parole. The DOJ said there is “no existing framework for compensation” or remedy for returnees once they are released. While there is one with the Board of Claims, the DOJ cannot guarantee their entitlement to compensation provided by law.

While the women still left inside have immediate release as their top priority, Xandra wants accountability from those who unjustly kept them detained.

“Sana managot ang CIW, lalo na si Marasigan, dahil siya ang nag-utos na pumirma kami ng waiver,” said Xandra. (I hope CIW becomes accountable, especially Marasigan, because she was the one who ordered us to sign waivers.)

“Sana nga po magawa ng BuCor yung utos ni (Justice) Secretary (Menardo) Guevarra. Napakalaking perwisyo ang ginawa nila sa amin. Kung totoo lang ang kulam, pinakulam ko na sila,” she added.

[I hope BuCor is able to follow (Justice) Secretary Guevarra’s order (to send us home by Christmas). They caused us so much inconvenience. If only witchcraft were real, I would have hexed them by now.]

Meanwhile, Bautista hopes to better prison conditions, especially after hearing reports about inadequate medical services.

“Actually paglapag na paglapag ko dito, infirmary ‘yung pinuntahan ko. Eh wala nang doktor dito. Recently may dumating na doktor, at nag-request ako ng assistance na every, kahit once a week man lang, may makapuntang doktor dito para mag-attend sa kanila,” she said.

(Actually as soon as I got here, the infirmary was the first place I went to. There is no doctor here anymore. Recently, a doctor came, and I requested for assistance that maybe a doctor could come at least once a week to attend to the detainees.)

“Nanay din ako eh. Alam ko concern nila kasi pareho lang kaming babae,” she added. (I’m a mother, too. I know their concerns because we are all women.)

But the returnees at the CIW rarely complain about the facility conditions. Their only wish is to be home in time for Christmas. (To be continued) – with reports from Lian Buan/Rappler.com

READ: Part 3 | Bantag tries to slay Bilibid’s old monsters, Duterte-style

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of the returnees.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.