SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

(Editor’s note: This story was first published in Newsbreak magazine on December 1, 2007, as part of its series on the counterinsurgency campaign of the Arroyo government. The interviews were made with military officers – many of them now retired – as well as communist leaders during the administration of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. Much of the thinking and tactics employed by the military under Arroyo is also being done now under the Duterte government – although in varying degrees. We are reprinting this story to put the government’s current counter-insurgency measures in perspective.)

MANILA, Philippines – If you’ve been fighting a war for more than 3 decades with no peace in sight, what do you do? Do you still toss in bed dreaming of victory? Do you still caress your gun, even if it’s lost one battle too many?

In the battered plains of Central Luzon, it’s easy to understand why the war with communist guerillas had taken a detour into a zone where soldiers abduct anyone who quacks or barks like a rebel, sometimes shooting them even if unarmed; where communist comrades have turned into mortal enemies, fighting over tiny patches of land and fishponds; and where ordinary citizens – perennially caught in between and now numbed by it all – could only sit and stare.

We visit a camp of Marxist guerrillas against the backdrop of Mt Arayat in Pampanga, which had played host to rebellion since the colonial years, and we see young men and women in fatigues, hoods, cell phones – but sharing just a few high-powered firearms. We talk with two of their senior political officers who had bolted the communist party to build their own practically from scratch. To punish them, the New People’s Army (NPA), the communists’ military arm, disarmed the separatist cadres and shot some of them dead. Twenty lives were lost on both sides in the shooting war among comrades in that long summer of 2001.

In Pampanga, commanders of the two factions – both claiming to be pushing for a national democratic revolution – draw the line: the western side remains with the NPA, while portions of the eastern side are left with the breakaway Rebolusyonaryong Hukbong Bayan (RHB). In other provinces in the region, they quarrel over little territories.

“The NPA does not have the franchise for waging a revolution,” says Ka Leandro, one of RHB’s political officers who joined the communist movement nearly 30 years ago and who sat down with Newsbreak one rainy day in August in the middle of a farm in Pampanga – still fired up.

But the communist pie that’s shared by the various guerilla factions has shrunk over the years, and Ka Leandro knows it.

Militarized region

Yet, gauging from the deployment and operations of Army troops here in the last 3 years, one would think that the region was on the verge of a revolution.

Soldiers immersed themselves in villages, preaching against the evils of communism and organizing residents into a network of informants. They dug up old files of ex-rebels who had returned to the mainstream. They hauled them to a new wave of interrogations – never mind that they were already running small businesses or working as employees – to see if they still had links to the communists. They put activists on everyday surveillance and identified their allies from among local politicians. They sowed fear where it mattered, and forged friendships where the anti-communist cause had been won.

The military’s intense presence in Central Luzon from 2004 to 2006 did not match the locals’ need for it.

Bulacan, which witnessed the most number of disappeared persons (26 as of April 2007), had the highest per capita income in the whole country by 2000. Three provinces in the region – Nueva Vizcaya, Pampanga, and Bulacan – belonged to the top 10 provinces that enjoyed high human development indices, according to the 2005 Human Development Report of the United Nations Development Program. This means residents there get much better services than the rest in the country.

We’re talking here of a region that roughly had 200 armed guerrillas – and 5,000 Army troops that operated against them. In the years after the Marcos dictatorship, from 1986 to 2004, not one province in Central Luzon witnessed big encounters between soldiers and rebels. The most fiercely fought battles then took place in Northern Luzon, Southern Tagalog, Bicol, and Eastern Mindanao.

So what was the military fuss all about?

This is a war that has gone on too long. Too long that commanders have been left to their own devices, executing counterinsurgency doctrines and tactics according to their own styles and appreciation of terror – without clear lines of accountability to civilian authority if they overdo it.

Too long that a bloated Army, now faced with only 7,000 armed guerrillas (and declining), has encroached on virtually every aspect of civilian governance – from operating in the cities to building homes to catching thieves to settling community disputes to campaigning in elections – all in the name of finally putting an end to what officers now view as essentially a political war against the insurgents.

Two-pronged strategy

Over the last 3 years, from Central Luzon to Eastern Mindanao, hundreds of activists have been killed, abducted, and harassed. From 2004 to end of 2006, political cadres of the NPA were liquidated by hooded men on motorbikes. Previously covered by immunity from arrest and harassment before the breakdown of the peace talks in 2004, at least 13 local officials of the communist-led National Democratic Front (NDF) have been abducted. They include two of the NPA’s suspected chiefs, Pedro Calubid and his alleged successor Leo Velasco, who had served as NDF consultants in the failed talks.

On the other hand, troops have stayed with populated communities, befriended residents, and set up government projects that ideally would have been done by local government executives.

These are two different – extreme, if you will – executions of one strategy that springs from a single mindset: that the war should now be waged among the masses of unarmed people who continue to sustain the revolution.

We sit down with several combat and staff officers to ask them what has changed in the insurgency landscape over the years, and how they’re dealing – individually and organizationally – with such changes.

A senior intelligence officer rants about the communists’ presence in Congress and their “abuse” of legal space, which he says justifies the killings of activists. We’ve been in this war for too long, he tells us, there’s nothing to lose. “These are producing results, they’re getting hit where it hurts,” he says of the killings without admitting if he’s part of the cabal behind these.

A troop commander 4 years his junior doesn’t buy the idea. “That’s not sustainable,” he tells Newsbreak when asked about the perceived value of extrajudicial killings to the government’s counterinsurgency program. And then he begins his long, passionate discourse on the many civic projects that he has implemented in his area with the excited eyes of one who’s immensely enjoying his newfound noncombat duties.

The military has been fighting the communists for nearly 4 decades already. It has implemented at least 4 campaign plans over this period (“Katatagan,” “Mamamayan,” “Lambat-Bitag,” “Balangai,” “Bantay Laya-1”), witnessed the fall of the Berlin wall, basked in the bitter split of the Communist Party of the Philippines, and declared the insurgents’ irreversible decline – only to realize they have crawled back to regain some lost foothold.

And then a new landscape emerged in 2001: it was suddenly faced with a guerrilla unit that was emaciated in the battlefield but whose political stock – through its control of leftwing political parties and a popular anti-government stance – has risen to levels never before seen since the height of the anti-Marcos years.

“We admit that there was a problem in the past,” says Colonel Ricardo Visaya, former battalion commander in Pampanga. “We were too focused on the armed group, even if we knew already that 70% of the enemy’s effort is [focused] on political struggle and that only 30% [is on] military struggle.”

Organizing barangays

Colonel Gregory Cayetano, another battalion commander in the region at the height of the military campaign against the Left there, adds: “We need a paradigm shift from the traditional role of conducting military operations. If we continue to see the enemy only as the armed threat that needs to be [confronted] with arms, then this war will never end.”

Cayetano talks avidly about the barangay defense system (BDS) that he set up in remote towns in Nueve Ecija and which has landed under the “best practices” handouts of the Army.

The colonel organized barangay residents as the Army’s key informants in the area. The Army didn’t arm them, he claims. The residents only had to text a hotline if they spotted a rebel or sensed incursions and, presto, the troops would arrive in the area. Through their everyday presence, the troops were able to secure the villagers’ obedience.

Cayetano’s BDS has not been adopted by the entire Army organization; it operates only in Central Luzon. He did it at Jovito Palparan’s behest, combining previous practices and drawing inspiration from his passionate and hardworking commander.

To be sure, this is nothing new. Cayetano himself concedes that it is the modern-day version of the dreaded Alsa Masa vigilante group that sprouted under the Marcos dictatorship, though he takes pains to emphasize that the BDS is not armed and that it has taken further steps to sustain itself through livelihood projects.

The BDS has 3 goals, according to him: it serves as real-time intelligence for the Army; it stops petty crimes in the barangays such as cattle rustling; and it provides livelihood to the residents. The BDS in Guimba town has since put up small businesses such as growing and selling mushrooms.

Cayetano recites 5 steps toward progress and communism’s defeat: stabilize the government, help fathers earn for the family, ask people to vote wisely, advise them not to rely on doleouts, and, finally, “put God in the center of their lives.”

He admits he had asked villagers in Nueva Ecija to vote for a certain local politician in the last elections, but the candidate lost. Cayetano doesn’t see anything wrong with campaigning for good candidates, if it redounds ultimately to driving people away from communism.

Playing politics

This is a view shared by a younger officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ramon Yogyog, who wrote a controversial paper in 2005 while finishing his advanced military studies at the Army Command and General Staff College. To crush the NPA today, the Army must deprive the rebels’ front organizations the chance to win in elections, he says.

“If the defeat of the [NPA] involves political, socio-economic other than purely military solutions, then the [military] should look at the window of political warfare,” Yogyog writes. He thinks that the military can – and should – influence local politics because of the new situation that has allowed communist fronts to seek elective posts.

He proposes: “A company of soldiers [with a] detachment in an influenced barangay can register in the municipality…by buying residence certificates…and [registering] with the local COMELEC as voters in the barangay where their detachment is located. When questioned why they don’t have properties in the area, the ready argument is…even squatters in the cities who live under the bridges are considered residents of Makati or Davao City, how much more the soldiers who live in said detachments for 2-5 years. Upon qualification as a barangay resident, the 70-100 soldiers can now help vote into office the [military’s] allies.”

We ask Yogyog about his paper, and he admits it was unpopular among many of his colleagues, but for other reasons. They felt that his concept of barangay-level organizing seemed a surrender of the “warrior” duties of a soldier. But that’s where the real problems lie, in the localities where governance fails, says this combat-tested Scout Ranger officer who joined the December 1989 coup and vowed never to repeat that misadventure.

He is aghast at suggestions that the Army should stay away from political affairs. “Our work is connected to politics, people in the field always ask us about anything under the sun,” he says, adding that every now and then he would volunteer to write project proposals for local officials, who could not read or write. “We are the link between the people and civilian governance that doesn’t always work.”

Yet in the same breath, Yogyog recalls that period not so long ago that prompted him as a young lieutenant to join a mutiny against the government.

It was 1989. The communists were at their peak, soldiers were demoralized, and military commanders grappled with an incoherent strategy against the insurgents. Hundreds of troops joined the coup that year largely because of “the bottled-up resentment, anger, frustration with how the counterinsurgency campaign was going.” When coup plotters proposed a change in government, many Army officers saw this as a way out of the situation, Yogyog says.

The counterinsurgency carrot

President Arroyo seems to understand this part of the soldier psyche very well, for she has used the heightened campaign against the communists as the perennial carrot to the military in exchange for its loyalty.

In her most troubled years from 2005 to 2006, the military made its presence most strongly felt in the regions surrounding the seat of power and where alleged communist fronts won overwhelmingly in the 2004 elections: Central Luzon, Bicol, and Southern Tagalog. While adopting varying tactics, the commanders in these areas had a single marching order from the top: deal a final blow to the guerrillas and disable their political network.

By this time, the Left had been leading ouster moves against the President. In 2005 alone, there was a 583% increase in extrajudicial killings from the previous year, according to data culled by the government’s own technical working group created under the government peace panel with the communist rebels. The group made an inventory of the killings and came up with a total of 240 activists killed from 2001 to December 2006 – a far cry from the claim of 800 victims by Karapatan and 118 by the National Police.

The study noted the same pattern, however: Central Luzon accounted for more than one fourth of the number of victims, followed by Bicol, Mindoro, Davao, and Southern Tagalog.

In its 2007 assessment of Oplan Bantay Laya 1, the Armed Forces cites the following deficiency in its counterinsurgency campaign: “Only about 20% of the actual neutralized personalities are in the Order of Battle list.” Neutralize means 3 things to the military: arrest, hurt, or kill. In the same document obtained by Newsbreak, the AFP made another table on its legal offensives. Does this mean that the table on “neutralization” did not refer to arrests?

Philip Alston, the United Nations special rapporteur who investigated the human rights situation here, directly attributed the killings and harassment to the military’s counterinsurgency strategy, a claim that Armed Forces chief General Hermogenes Esperon Jr denies and resents.

There’s also the regime stability factor. Commanders in areas near Metro Manila were under tremendous pressure to achieve one thing: to prevent leftist activists from joining mass protests in the capital. By the time he retired in 2006, Palparan could boast that leftists in Central Luzon could not even bring a busload of rallyists to Manila.

Yet, the difference in commanders’ styles is palpable, proof of the perennial leadership problems in the military – unless, of course, it was purposely designed this way.

In Southern Tagalog, then 2nd ID Major General Fernando Mesa (now chief of the National Capital Region Command) launched his do-gooder “Pogi” squads in communist influenced areas. They exerted little terror, doing more CMO (civil-military operation) work instead. In areas where the rebel presence was nil, they helped residents build houses, constructed roads, organized youth camps. By early 2007, the division had become a model of sorts, with the Americans even noticing this by deploying some of their troops there to conduct joint civic work with Filipino soldiers.

The Palparan doctrine

Central Luzon was something else because its commander was something else, too: Jovito Palparan. (Editor’s note: Palparan is now in jail)

Palparan claims not to adhere to any doctrine except the “Palparan doctrine.” When asked about the much-criticized military campaign plan Oplan Bantay Laya, he says: “I don’t even understand it…too many theories there, it’s a whole government effort.”

In his doctrine, Palparan’s troops have only two objectives: paralyze the enemy’s ability to fire and stage rallies, and organize residents who will defend themselves against the guerrillas, “fight if necessary.”

In the usual military practice, a commander selects which barangays need military presence so he could deploy troops there. This isn’t the case with Palparan. “We cleared all municipalities regardless, went to each barangay, and made our presence felt,” says one of his former deputies.

In Bulacan, faced with just an estimated 40 NPA rebels, the Army treated the whole province as the water in which the guerrillas were able to swim. They stayed in each village, held a series of seminars on communism, and organized residents into self-defense units whose officials – separate from the elected barangay leadership – reported directly to the Army. They ensured peace where the local police couldn’t, and served as the complaints center for residents for all sorts of woes.

Naturally, the local officials protested. But they relented and cooperated eventually, says an officer who led the operations. “We would have been too blunt if we told them we were doing what they were supposed to do as local officials.” He adds: “If you leave the problem entirely to us, we will just solve it the military way.”

The Palparan doctrine includes local officials as likely enemies, especially in areas where they are suspected of supporting guerrillas. “You can tap their help,” Palparan says of local executives. “But most often they are also affected, they give their IRA (internal revenue allotment) to the rebels, so you have to neutralize them first.”

Despite a dismal human rights record, Palparan’s stars rose fast under the Arroyo government – a mockery of existing rules that require officers to be cleared by the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) before they’re promoted. Seven complaints had been filed against Palparan but because none were concluded, none was used to block his promotion.

The general was given the leeway to execute his doctrine in various ways. His immediate superior then was retired Army chief Lieutenant General Romeo Tolentino, an Arroyo loyalist who was at the time commader of the Northern Luzon Command.

Palparan praises Tolentino for his support. When the latter became Army chief, “he used me,” Palparan says. When asked to elaborate, he explains: “General Tolentino deployed some of my men to three areas in Bicol and Mindanao to implement my doctrine,” but it hasn’t been completely successful. “Commanders must not only be good. They should have courage.”

He notes that there are only a few aggressive commanders around who understand the psychological aspect of the war. That’s why he doesn’t think the insurgency will be defeated according to the President’s 2010 timetable. “You cannot expect to win just by seizing firearms.”

With words like this, Palparan could get convicted. But ask anyone who has been under him and you’ll hear praises for this general, who managed to awaken the warrior even in soldiers tired of this war. The development aspect of counterinsurgency, he says, is mere decoration.

Political warfare

This runs against what is now being pummeled into commanders’ heads: that the military is in transition to becoming an active organizational development partner of the government. The Armed Forces, in fact, has set up a new command, the National Development Support Command (NDSC) that finally institutionalizes the development aspect of their work.

All this bears scrutiny.

Unfortunately, the civilian leadership has not put together the military’s disparate tactics and thoughts on insurgency into one coherent whole, or taken a critical look at the military’s deepening involvement in civilian work.

Just three years ago, in fact, the military command abolished all its CMO units and put them under operations. The effect was a reduced importance of CMO work in the armed forces. “That had a big impact on us,” says Major General Jaime Buenaflor, formerly deputy chief of staff for civil military operations and now commanding general of the NDSC.

To be sure, military strategists have long emphasized the political nature of counterinsurgency warfare, and the prevailing view – now resurrected amid the United States’ inability to pacify Iraq through brute military power – is that to defeat guerillas one must provide people with what a rebel army cannot: roads, bridges, businesses – in short, better government.

This thinking puts popular support as a precondition to a successful counterinsurgency program.

Yet, other military theorists such as Edward Luttwak question this thinking. “Government needs no popular support as long as it can secure obedience,” Luttwak says in a recent critique of the development aspect of the US counterinsurgency program in Iraq. To defeat insurgents, armies must be able to “out-terrorize” them, he says.

Obviously, there are as many Luttwak advocates as there are critics in the Philippine military.

Cruz vs Gonzales

At the policy level, resigned defense secretary Avelino Cruz Jr did not share National Security Adviser Norberto Gonzales’ view that the communists remain the most immediate and biggest threat to government.

Cruz plodded along with his strategic, institution-based reform program, while Gonzales found soulmates in the military who shared his anti-communist fervor. Cruz insisted on a long-term, 10-year effort to defeat the insurgency, while Gonzales declared that government could finish them off in two to four years. President Arroyo herself was eventually convinced that the 10-year period was too long. Cruz would eventually be proven right. In its 2007 assessment, the AFP said it could only wipe out the insurgency by 2018.

Cruz also won on a key appointment. He handpicked Palparan’s successor in Central Luzon, Major General Juanito Gomez, who had previously endeared the Army to residents and officials of Bohol, where he worked well with the local populace. If you’re wondering why Central Luzon seems quiet today, that’s because of Gomez.

But Cruz eventually quit the Cabinet in November 2006. Gonzales ally and adviser Jesuit priest Romeo Intengan clapped with glee. Without Cruz, he wrote, “the Cabinet will be more united in pursuing the total approach to the insurgency according to the accelerated timetable set by the President.”

Culprit: ‘White Area’

Such a total approach has meant maximizing all efforts against insurgents based on a new understanding, post-2001, that the war has ceased to be in the battlefield.

The communists’ focus on political work following their rectification campaign in 1992 was met with shortsighted thinking on the part of the government. Following the repeal of the Anti-Subversion Law, the government decided to give the National Police the lead role against the insurgents, thinking that the Armed Forces could then begin flexing its muscles for external defense.

But the National Police itself, born just in 1991, with the merger of the old Constabulary and the Integrated National Police, was in a difficult transition. Soon the insurgency effort returned to the Armed Forces, which by that time was bogged down by corruption, inefficiency, and politics.

Thus, when the military broke away from Estrada in 2001 to catapult Mrs. Arroyo to power, it found itself in a broad coalition that included the Left. In 2001, alleged communist groups won in party-list races, and that’s when the staunchly anti-communist Gonzales smelled danger.

As presidential adviser on special concerns at the time, he asked his staff, led by retired Major Abraham Purugganan, to draw up a framework on the new insurgency landscape. Purugganan and his team came up with a paper on the insurgents’ “white area” operations.

The term “white area” was coined by the guerrillas themselves, to refer to a place, usually urban, where government agencies are situated but where the revolution gets crucial support from the middle class, businessmen, students, and other sectors, and where front organizations operate freely. The rebels had always considered it a support area.

In the late 1980s, Romulo Kintanar, the former chief of the NPA, pushed for further rebel concentration in the white areas, according to a former top guerilla. He explains: “It’s where the people are. You need to terrorize the white area…otherwise you won’t have impact.” (Come to think of it, this sounds like the Palparan doctrine, on another level.)

The period from the late 1980s to the early 1990s thus witnessed the height of the NPA’s urban insurrection, which exiled communist chief Jose Ma Sison criticized in his seminal “Reaffirm” document that caused a bitter Party split in 1992.

Since then, the guerrillas have avoided bringing the war to the cities. But it is their legal alliances that have made the loudest political noise in the white areas.

“We knew that the [rebels’] strength was coming from the white areas, but we had not found the tool or technology to address it,” admits an Army brigade commander. “After 2001, that’s when some of our thinkers came up with a doctrine and tested it.”

A White Area policy paper from Gonzales’ office that was eventually fused with Oplan Bantay Laya reads: “The AFP is following the old military philosophy that the diminution of the coercive power of the NPA can cause the whole revolutionary activity to fall. This is no longer the case. The current setup of the whole insurgency suggests that the military pressure has to be applied [on] all fronts and against all personalities simultaneously in order to create an impact.”

Purugganan explains that the government strategy was meant to be a holistic, multi-agency, institutional approach to counter the strength of the guerrillas in populated communities. The plan was to launch an information drive among civilian agencies on the presence of front organizations in populated areas, on what they do, where they get funding, and how to stop them – legally. It was clear at the onset that dealing with the white areas was “beyond the military’s capability,” says Purugganan, who has since left Gonzales office and now heads a risk consultancy group.

But due to the lukewarm interest of civilian officials, a former Palace official says, the Armed Forces went their own way to add white area operations in its counterinsurgency doctrine and as a key brainwashing tool among commanders – despite doubts over the commanders’ grasp of the nuances of the situation and the likelihood that it was open to various interpretations.

Under Oplan Bantay Laya 1 and 2, one of the key objectives stated in secret military documents is to “neutralize the White Area command and communist movement personalities in sectoral organizations providing support to the…armed struggle.”

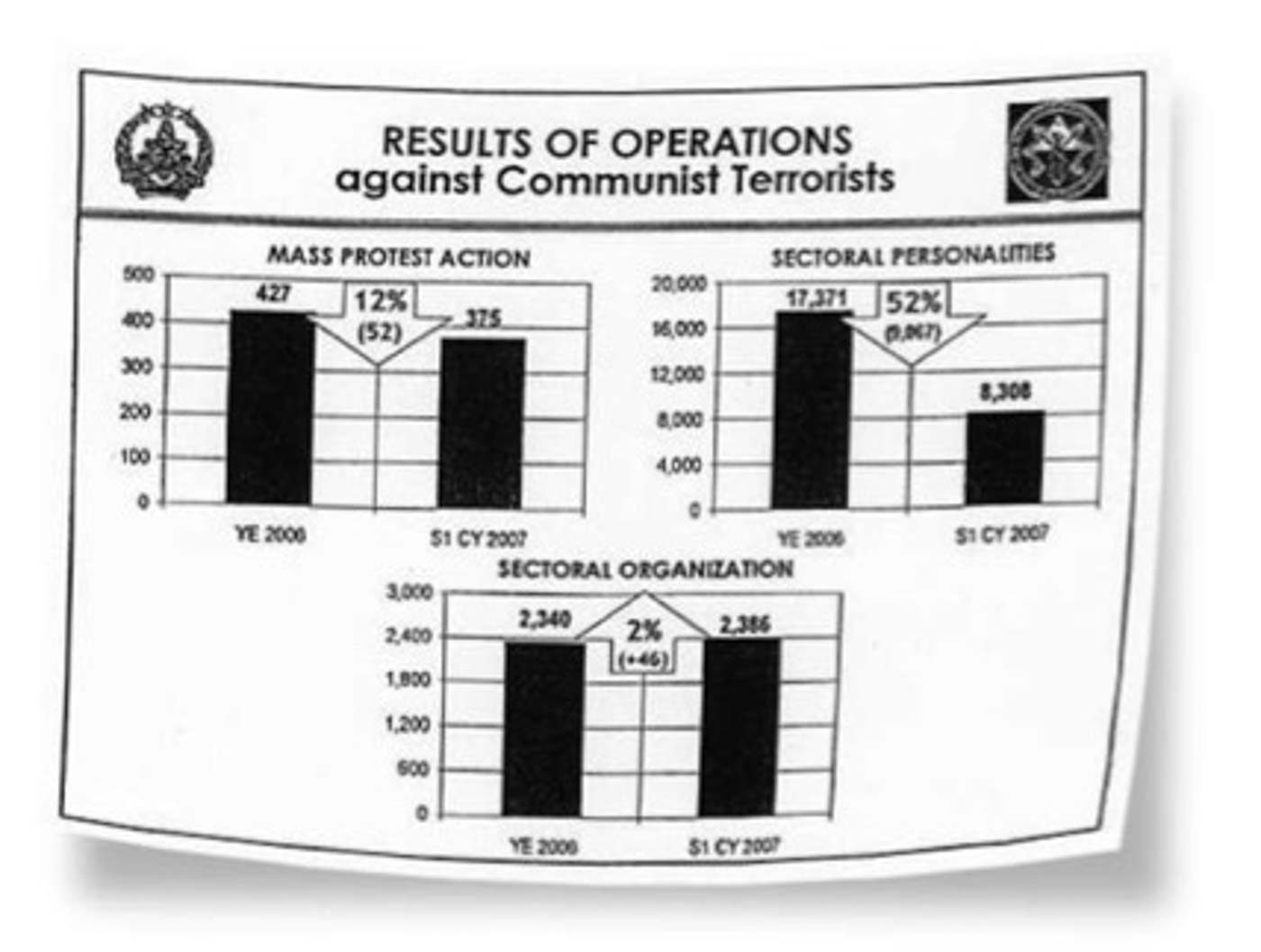

The documents, in fact, cite “results of operations” against “sectoral personalities” that led to a 52% decline in their number.

Indeed, in an ideal world, civilian institutions and agencies should be the ones drowning out the political noise in the “white areas.” Not in the Philippines, where the military is at the forefront of intense political work against the Left – by all means fair and foul. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.