SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Billie* sat alone in a white isolation tent of a small public hospital in Quezon City. It was hot and humid inside, not a single electric fan to keep the summer heat down. It was the 17th of March, a day after Billie learned someone she had gotten in contact with tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

She remembers speaking to that colleague face-to-face on March 11, but he would inform the office about his positive results only 5 days later on March 16. He made no mention to anyone at work that he was already experiencing symptoms and that he had gotten himself tested for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

Between March 11 to March 16, Billie started having a dry, scratchy throat. She suffered a headache for two days straight. Later on, she felt her lymph nodes getting swollen. Her throat would ache several times a day.

These, according to the Department of Health (DOH), are among the symptoms of COVID-19.

Billie decided to have herself checked after she confirmed she had direct exposure to a positive case. But because the entire island of Luzon was already on lockdown due to the outbreak, she could not commute. She didn’t want to ask her father to drive her to the hospital either, out of fear she would infect him.

Billie started walking.

She arrived at the hospital 40 minutes later. She was told to stay inside the isolation tent, and waited for 4 hours before a nurse donning protective gear from head to foot started getting her vital signs. The nurse took her specimens.

“Kukuhaan ka sa throat mo. Medyo maduduwal ka ‘pag ‘di mo kaya, kasi malalim talaga ang pagkukunan nila. Tapos lagpas sa bridge ng nose kukuhaan ka din so parang mag-si-sneeze ka after i-swab,” Bille said, describing the uncomfortable experience.

(They’ll take a specimen from your throat. You’ll end up retching if you can’t take it because they’re going to take the sample from deep within your throat. They’ll also take a swab from inside your nose, higher than the bridge, so you’ll feel like sneezing right after too.)

Billie was classified as a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19.

By the time the swabs were taken from her, it was already 6:30 pm. Billie knows from reading the news that the DOH had said COVID-19 test results normally take 24 to 48 hours to be released. She asked when her results would come. At least a week, the nurse said. Billie could only purse her lips.

“‘Di daw sila makakapangako na agad makukuha ko ang result kasi even my case, mild symptoms lang ako. Siyempre i-pa-prioritize ‘yong severe and critical,” Billie said. “Naiintindihan ko naman, pero nakaka-add sa anxiety bilang isang tao na na-expose sa COVID-19.”

(They told me they couldn’t promise I would get my results immediately because my case is just mild. Of course they have to prioritize the severe and critical. I understand, but it just adds to the anxiety of a person like me who was already exposed to COVID-19.)

Billie is not alone. All over the Philippines, people are waiting in agony to learn if they really do have the deadly, fast-spreading disease. Many individuals already showing symptoms are being turned down by cramped hospitals struggling with lack of space and dwindling supplies. Worse, others die long before they could even confirm it was COVID-19 that had killed them.

Left with no choice

The situation isn’t any better in private hospitals.

Michael* has been camped outside the emergency room driveway of a private medical facility in Pasig since March 19. He had to rush his 56-year-old father Ernesto* there after he started having difficulty breathing.

Ernesto was also having on-and-off fever for over two weeks now, and eventually developed pneumonia. Ernesto is hypertensive, making his severe COVID-19 symptoms even more worrisome for his family.

Michael does not know yet if his father has the coronavirus. On March 16, Michael brought him to a clinic in Cainta because his father’s symptoms weren’t improving. A blood test and X-ray were done, after which they were sent home. Still, Michael said the clinic got in touch with the DOH to inform them about his father’s condition.

Two days later on March 18, a DOH team came knocking at their house and took swabs from Ernesto. Michael was told his father’s COVID-19 test results wouldn’t come until 3 to 5 days later.

The next day on March 19, Ernesto couldn’t breathe properly anymore. Michael called medical facilities around Metro Manila asking if they would take in his father. They said no. Finally, the hospital in Pasig said yes.

“He’s in a more stable condition now and we’re just waiting for a room in the ICU,” Michael told Rappler. “But getting to this point was hell on earth.”

It was pure chaos when father and son arrived. Michael recalled seeing people flocking to the hospital and trying to get themselves or their relatives tested. Doctors and nurses were scrambling for rooms. Most of the patients Michael saw being admitted were in their 50s – the age range of most of the 307 patients in the country who have tested positive for COVID-19 as of noon of March 21.

Ernesto was first moved to the hospital’s center dedicated for patients suspected of having COVID-19. On March 20, he was moved to a smaller isolation room, but it was still far from ideal as he was sharing the space with 3 other high-risk patients.

But Michael knew the hospital had no other choice.

“I’m so scared for people without the resources. I’m so fortunate that I have a health card, easy access to an ambulance, and I’m capable of paying bills in this hospital,” Michael said. “I’m having a hard time as a privileged person. What more people without the help?”

Disregarded triage for testing?

That the Philippines has a shortage of test kits is a tragedy felt across provinces. Many local government units outside Metro Manila are forced to battle COVID-19 without determining just how many of their people actually have the disease.

For the longest time, the Philippines had only the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) to test COVID-19 samples. Now there are 4 other subnational laboratories duly accredited by the World Health Organization (WHO), but they are not yet on full capacity.

These are the Baguio General Hospital and Medical Center in Baguio City, San Lazaro Hospital in Manila City, Southern Philippines Medical Center in Davao City, and Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center in Cebu City.

The country is also mostly relying on donations from the WHO, as well as local and foreign bodies for additional test kits. This is compounded by the growing demand for coronavirus extraction kits around the globe, where at least 161 countries have recorded over 246,400 cases of COVID-19.

This is precisely the reason why the DOH updated its decision tool for testing on March 16 – to help ensure the more vulnerable of the population get to be tested first given the severe shortage of test kits. This decision tool guides healthcare workers in categorizing a patient as either a person under monitoring or investigation, or neither. (READ: Coronavirus mass testing not needed for now – DOH)

Only PUIs showing severe symptoms and who have been exposed to a positive case or have traveled to a country with local transmission are supposed to be the first in line for testing. The elderly, pregnant women, and individuals with underlying medical conditions already showing symptoms – even if these are just mild to moderate – are to be prioritized, too.

Persons under monitoring (PUMs) – people who exhibit no symptoms but either have history of travel or known exposure to a coronavirus patient – are not supposed to be tested yet. Rather, they are required to self-monitor while undergoing a 14-day home quarantine.

Yet it’s now clear the DOH decision tool is not being followed at all. One only needs to look at President Rodrigo Duterte’s family to confirm this. Swabs were taken at their homes in Davao City on March 17 even as people across the country have been denied testing because they do not meet the criteria.

9-hour wait for a test that did not come

John* even experienced being downgraded from being a PUI to a PUM in a span of just 9 hours.

A resident of Quezon City, where he works as an academic in a university, his job required him to spend a few days in February traveling around Malaysia and India to attend a conference. He returned to the Philippines on February 26, but his cough and cold came only about two weeks later on March 10.

He first went to a clinic but was told to proceed to a hospital already. Because he had a health card, John went straight to a private hospital at around 3 pm. He couldn’t enter the main hospital building and was told to stay at the waiting area outside the ER driveway, where a nurse and doctor interviewed him about his condition.

John was told he was already a PUI given his symptoms and travel history. The doctor told him he would have to undergo both a blood test and a COVID-19 test.

He was then moved to the emergency triage area for respiratory illnesses, a small, air-conditioned room not far from the ER. His blood test came back. The doctor said it “did not turn up any urgent concerns.” He was told to wait a bit longer for his COVID-19 test swab.

Hours went by until John was informed he had two options: he could either go home and undergo self-quarantine or just wait until the hospital gets the go-signal to take his swabs. The hospital staff was coordinating with RITM to determine if John really needed to be tested.

Another hour passed, another update from the doctor: John needed to be confined so he could get tested. He agreed; his health card would pay for it anyway.

He was once again moved to a smaller ward labeled “Suspect Infectious Room.” John’s sister came to the hospital to help him process his confinement papers while he stayed in the isolation room.

Nearing midnight on March 19 – after 9 hours of waiting – a doctor entered the isolation room and told John he couldn’t be tested after all.

“The reason relayed was that the countries I traveled to, India and Malaysia, weren’t high up anyway in the list of countries with cases. And that my symptoms weren’t very severe. I mean it’s cough and a cold,” John said.

He asked the doctor if he was still a PUI. No, said the doctor. You’re just a PUM now.

There was a tone of disappointment in John’s voice when Rappler spoke to him on the phone. “So that was a whole ordeal really of uncertainty and just confusion. We were astounded by the slowness of it all,” John said. “Why did it have to take several hours for them to make a determination whether I should be tested or not?”

The agony of waiting

The stories of Billie, Michael, Ernesto, and John are happening all over the country. They know there are qualifications they have to meet before getting tested, but the government does not inform them the whole process would take hours and hours.

There are inconsistencies in how the DOH decision tool is being implemented. Billie got tested in a hospital even with just mild symptoms, while Ernesto – who already had pneumonia and difficulty breathing – had swabs taken right at home. John was classified as a PUI, only to be told hours later that he could not be prioritized for testing.

There’s a general feeling of confusion as even medical professionals – who are already overworked and are in dire need of supplies and protection – scramble to follow the health department’s decision tool for testing.

The sad truth is this: the Philippine government was unable to anticipate an outbreak of this scale. But there are ongoing efforts to augment the country’s testing capacity.

When asked in a March 20 press conference why it is taking more than a week for COVID-19 test results to come out for many Filipinos, DOH Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire had to come clean.

“So ‘yon pong nababalita na medyo may delay, totoo po iyon (So those reports that there are some delays, those are true). We are being challenged right now,” Vergeire admitted.

DOH Secretary Francisco Duque III also said the delay in the release of results was due to RITM having to reconfigure its laboratory to ensure biohazard safety standards are still met despite the increasing number of specimens it needs to process.

There are assurances from DOH that testing capacity will improve in the coming days. Vergeire said the 5 subnational laboratories have the capacity to process 950 to 1,000 tests per day now, the bulk of which still comes from RITM.

Two more subnational laboratories are being eyed to eventually become extension testing centers for COVID-19: the Western Visayas Medical Center in Iloilo City and the Bicol Public Health Laboratory.

The DOH is mobilizing the laboratory of the University of the Philippines-National Institutes for Health, which developed its own testing kit, to help improve the government’s testing capacity. The Food and Drug Administration has also approved 4 novel coronavirus test kit products for commercial use, though these can only be purchased by hospitals and laboratories with testing capacity.

But the DOH has not disclosed just how much backlog these laboratories have. Whether the country has enough medical technicians skilled to interpret these COVID-19 samples is also an unanswered question.

Back on the streets, the already anxious are left with not much choice but to wait. They can only hope their test results – when they do finally arrive – would come back negative.

“Na-prolong ‘yong agony ko. ‘Di ko alam if positive ba ‘ko o hindi,” Billie said with a sigh. “Tinanggap ko na lang ‘yong sitwasyon.” (My agony is being prolonged. I don’t know if I’m positive or not. I just accepted the situation.)

Until when will this go on? – Rappler.com

*Names were changed upon their request to protect their privacy. These accounts are based on actual experiences.

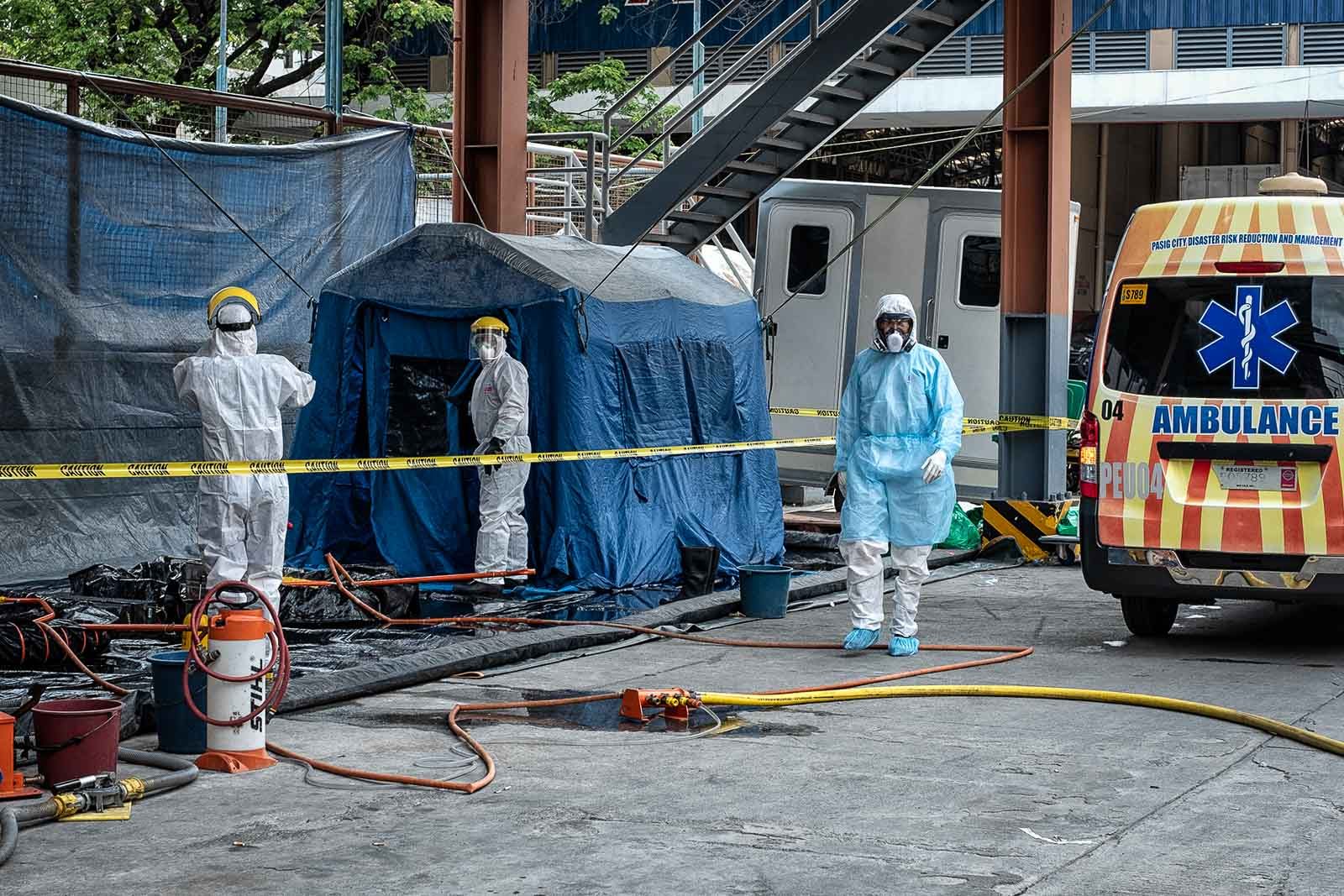

TOP PHOTO: ISOLATION. Security personnel check on the isolation rooms intended for COVID-19 PUIs at the Manila Infectious Disease Control Center of the Sta. Ana Hospital in Manila on March 8, 2020. Photo by Ben Nabong/Rappler

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.