SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The community clinic closes at five in the afternoon.

It sits along the main road of the village of Mambog I in Bacoor, Cavite. When the patients leave, the nurses stay. They draw up the schedule, line up the appointments, and decide who comes in first the next morning. Mass transportation is suspended, so one nurse from Kawit bought a bicycle. Two others ride motorcycles.

By six in the evening, all but one staff member of the Health Index Multispecialty Clinic has left for home.

The man who stays behind is a 28-year-old janitor named Rowel Togo. He begins work in the doctor’s office. He wipes down her table, sanitizes her chair, decontaminates every surface. He sweeps. He mops. He begins the long, complicated process of what he calls “walling.” He sprays each wall with disinfectant, then rubs them down, three times, each time with a different rag. The first rag is wet, the second damp, the third dry. It is a technique he learned when he worked at a local Chowking: spray, wipe, wet, damp, dry.

He goes room by room. Pediatrics. ER. Obstetrics. Ultrasound. X-ray. Pantry. Internal Medicine. General Medicine. Admin. He closes the doors to let the disinfectant do its job. He sanitizes the reception area next, where the long bench that used to fit six patients is now limited to three.

The hallway comes after. He sweeps. He mops. He sprays and wipes and repeats, sometimes mounting a small stool whenever his five-foot-six-and-a-half inches aren’t enough.

He takes a break after the hallway. The doctor, he says, isn’t terribly strict about time, so long as Rowel gets the job done. He steps out to smoke one of three cigarettes another staff member shared that day.

It is quiet on the streets. There are no passersby or rattling tricycles, only the occasional cop with a loudspeaker reminding residents to go home. Rowel chats with the security guard outside the front door. He scrolls down his timeline. Then he goes back inside, to scour the tile of the restroom walls.

He locks up at ten in the evening, five hours, nine rooms, and thirty-nine walls since he started. He gets on his bike and pedals the half hour home to Mambog III. He carries with him the two cans of sardines he picked up on the way.

There is a bucket of water in the yard outside his house. His wife has left a folded towel, a bar of soap, a pair of shorts, a shirt, and the gallon of 70-percent alcohol he bought with the clinic’s other supplies. He takes a bath. He rubs down with alcohol, every inch. He gets dressed, opens the door, calls out a greeting, then waits for the screaming joy of two small boys who leap into his arms.

‘Proud ako’

Cavite’s population of more than 3.6 million lives just south of Metro Manila, the teeming center of the country’s coronavirus outbreak. The governor’s March 16 announcement of a state of calamity closes down malls, cancels parades and sends sidewalk vendors home. A curfew is imposed, along with a community quarantine.

All of this means a number of things for Rowel Togo. It means the clinic shifts from 24-hour operations to a nine-hour workday, eight to five, four days a week, with breaks for decontamination. It means Rowel mans the door in the daytime, letting only one masked patient at a time – “We have to do social distancing, ma’am.”

It means, finally, that at past five in the afternoon in the beginning of the lockdown, Rowel is left to work alone for the first time in the four years since he was employed as a janitor. There is no night shift doctor, no more patients in reception. It is a change for Rowel, who likes his job because he likes the people. Every employee is a friend. He laughs with them, tells them stories, asks nurses about his father who had a stroke in September, sometimes records TikTok videos with his fellow janitor Mack.

On the first night, at a little past nine, Rowel takes pictures of himself inside the empty clinic. The white floors gleam in the fluorescent lights. A fabric mask covers half of Rowel’s face, and what little is visible can pass for a teenager on a day off from school.

He posts the photos online. “I am a Health Worker and I am proud of it,” the caption reads.

He does it again two days later, inspired by another janitor from another hospital. The caption over the photo is short.

I am not a doctor, Rowel writes. I am not a nurse. I am maintenance, utilities, a janitor. I am proud to be one of the frontliners.

The Philippine government’s most recent count, as of Wednesday, April 1, puts confirmed COVID-19 cases at 2,311, although the numbers are likely underreported with limited testing available. There have been at least 96 recorded deaths, at least six of them from Cavite. The province, where the clinic is, has racked up 28 confirmed COVID-19 individuals – including one mayor.

Experts have pleaded with the public to consider hospitals as only one of many fronts in the response to COVID-19. Containment, they say, requires concerted action from the community level.

In the photo he posts online, Rowel holds up a sheet of A4 paper, where, written out in black marker, is the same sign he had seen posted by doctors all over social media: “I stayed at work for you. Please stay at home for us.”

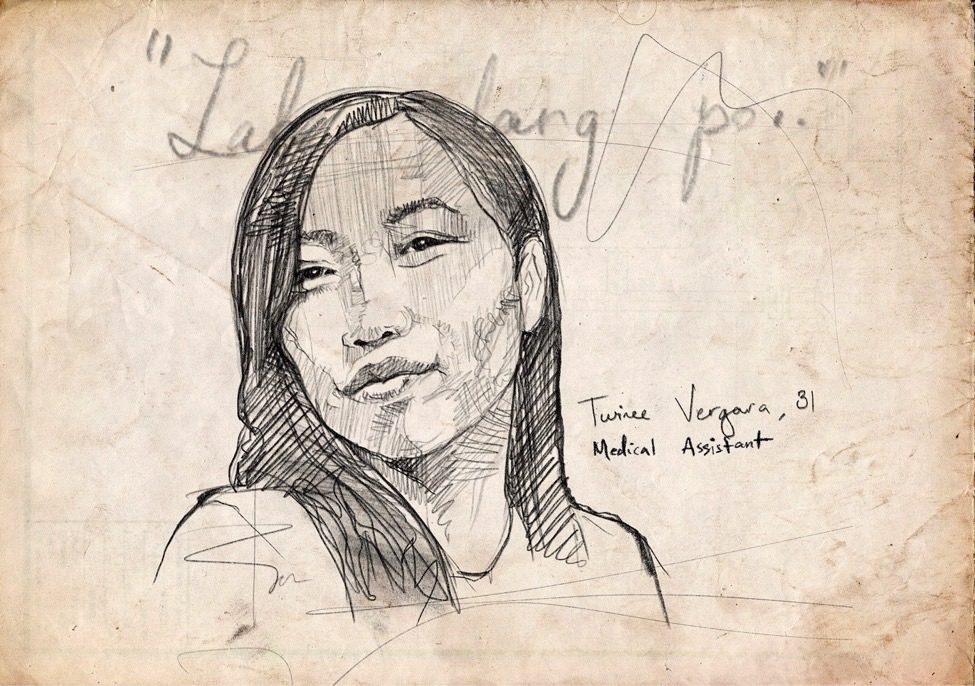

‘Laban lang po’

Her name is Ma. Rosela Vergara-Vivero. She was born in Capiz, the youngest of seven. Her twin sister died at birth, so Rosela’s grandmother called her Twinee, to make sure she never forgot that she came from a matched set of two.

Twinee remembers wanting to be a nurse in kindergarten. She left home for Las Piñas to study, went to nursing school, but never passed the boards. There was no money for the nursing board reviews. She was twenty years old and sitting in a bus when a young man turned around to ask for her phone number. She saw he was with a pair of varsity players she knew. She thought he was cute. She handed over her number before she found out he wasn’t from her school at all but was instead a seaman out from Bacolod on a trip to Manila. They were dating two weeks later and married four years after that.

At 31, Twinee has spent most of the last ten years working at Health Index. She is a medical assistant at the clinic, a private outpatient facility that serves the cities of Bacoor and Imus. Her husband gave up seafaring to take care of the baby. Twinee couldn’t imagine leaving the clinic, so it was her husband who stayed home. He prepared meals. He watched over their son. Her husband was her rock and support, all the way to the day in February when they began to hear of a virulent new coronavirus.

The doctor had warned them all of COVID-19. Twinee thought at first it wasn’t serious – that it was just another flu, easily cured, quickly solved. It was only in early March, watching the news from Italy and China, that she began to worry.

Twinee has not considered filing for leave. Patient care is what Twinee trained for. It is a purpose she believes in, and Twinee believes in having a purpose. She will go to work for as long as she is needed.

She drives home every night after her shift. Her husband leaves a pail of hot water in the terrace outside their townhouse. Twinee strips down to bathe, wraps herself in a towel when she is done, and heads straight to the bathroom to soap down again. She shampoos her hair a second time. She rubs down her hands with a layer of alcohol. Upstairs, her husband keeps their son entertained to prevent the five-year-old from running to find Mommy.

Sometimes she cries. She is afraid of getting sick, and the necessary separation from her family it will mean. Her husband holds her. He tells her she can do it. He tells her she is strong enough and tough enough to fight. He has never told her to stay home.

His purpose is clear too: to brace her every night, so she can go back out the next day.

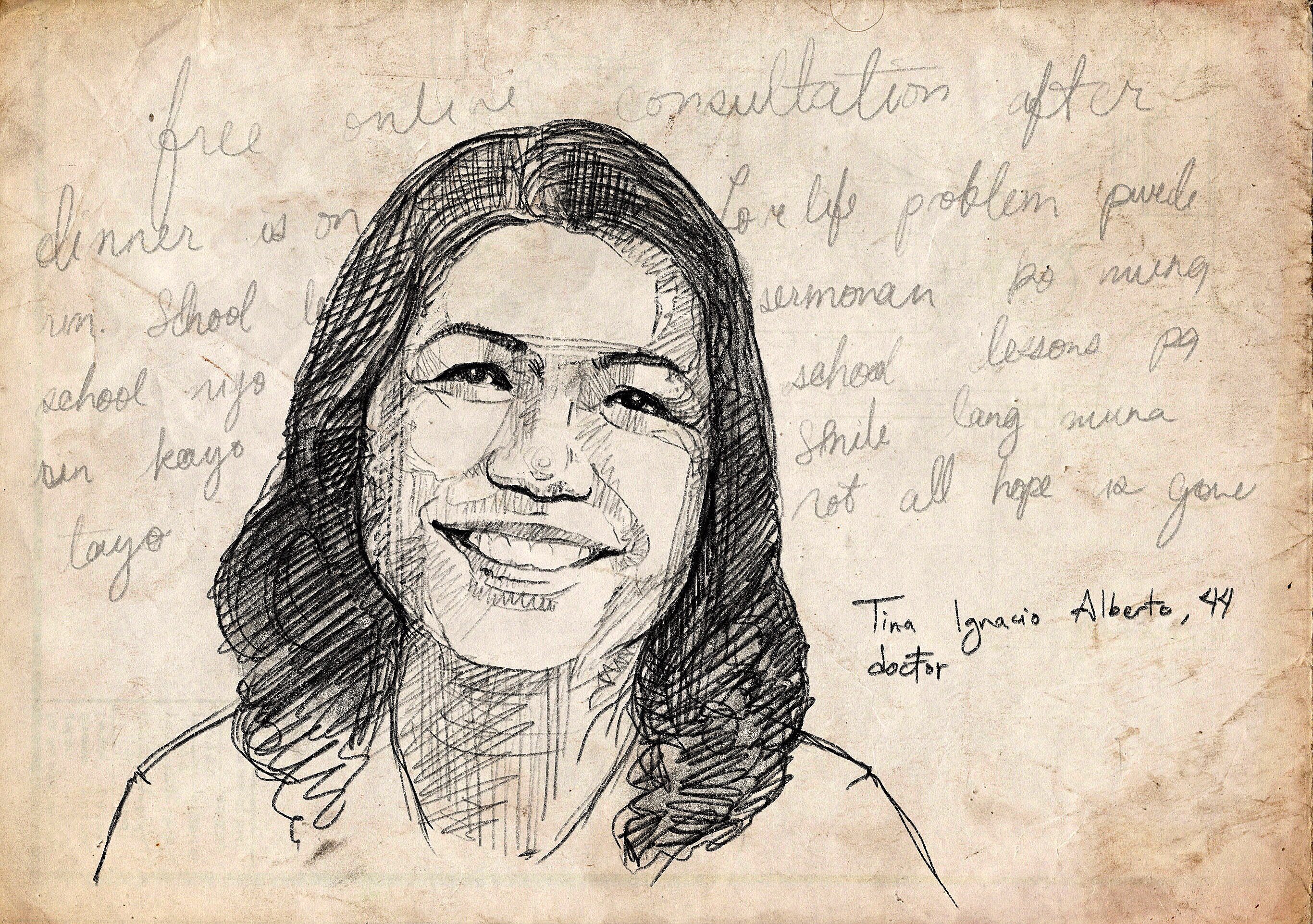

‘Wag po kayo umiyak’

The doctor’s name is Maria Cristina Ignacio-Alberto, “Doc Tina” to her patients, a 44-year-old pediatrician with three young daughters. She opened the Health Index Multispecialty Clinic in the same village she was born and raised.

It was a risk, she says laughing. She wasn’t sure the village of Mambog I would accept a doctor who once sold mangoes in the market and ran mud-spattered through their streets. Tina’s first clients were neighbors and elementary school friends. The clinic’s services have expanded since, with more than a hundred babies born inside the lying-in facilities. Many of them remain Tina’s patients today.

It is Tina’s choice to keep the clinic open through the quarantine, even as the ranks of the clinic’s health workers thin with only 15 from almost 30 still reporting for duty. People don’t just die of COVID-19, says the doctor. They also die of dengue and pneumonia after they are refused treatment. Some of those patients have appeared at the clinic’s door.

Health centers and the clinics serving communities – both public and private – are the linchpin of the health system, says Paolo Medina, a community medicine assistant professor at the University of the Philippines College of Medicine. “We’re handling COVID because it’s the enemy that’s there,” Medina says. “It’s something that’s top of mind. But even with COVID there, life doesn’t stop.”

Tina’s job is to stay the course and let her community clinic carry the urgent cases that would otherwise crowd emergency rooms. The cases range from herpes zoster to measles to lacerations to childhood asthma. Six patients with dog and cat bites have appeared in a single day. Patients with travel history and mild symptoms are told to go into isolation at home. Severe cases are sent to hospitals with the capacity to test.

Throughout the day, Tina offers free consultations online. The requests fill her inbox. Some of them are from regular patients, others from people she has never met from cities as far away as Iloilo. There is the parent asking advice for a child burned by a potful of boiling water (wash with Betadine, then Flamazine cream, twice a day) and the woman asking to interpret her father’s laboratory results (likely diabetes). There is the father, helpless and frustrated, who sent Tina photos of soiled diapers. His baby couldn’t keep food down, and he didn’t know what to do. “Don’t cry, we’ll get through this,” the doctor tells him.

The doctor suspects some who write to her are already positive for COVID-19. The man suffering from headaches and chest pain who had been turned away by three hospitals. The breastfeeding mother who had lost her sense of smell. The worker with symptoms who was told to pay for protective gear before entering a hospital. She tells them to recognize the possibility, recommends zinc and vitamin C, suggests they wear masks, use different bathrooms, and isolate from their families when possible. She adds them to her patient list, advises some to get tested, and monitors them daily.

Tina strips off the protective gear before she leaves for home. The mask is kept on. Her shoes are left outside the house, to soak in the sun and burn away pathogens. Pair after pair wait in a line along the driveway. The coronavirus, she says, can stay on shoes for five days. She puts on a different pair each morning.

We have a hashtag at home, says the doctor. Keep fighting – and if we die, we die for the country.

It is a joke she shares with her husband.

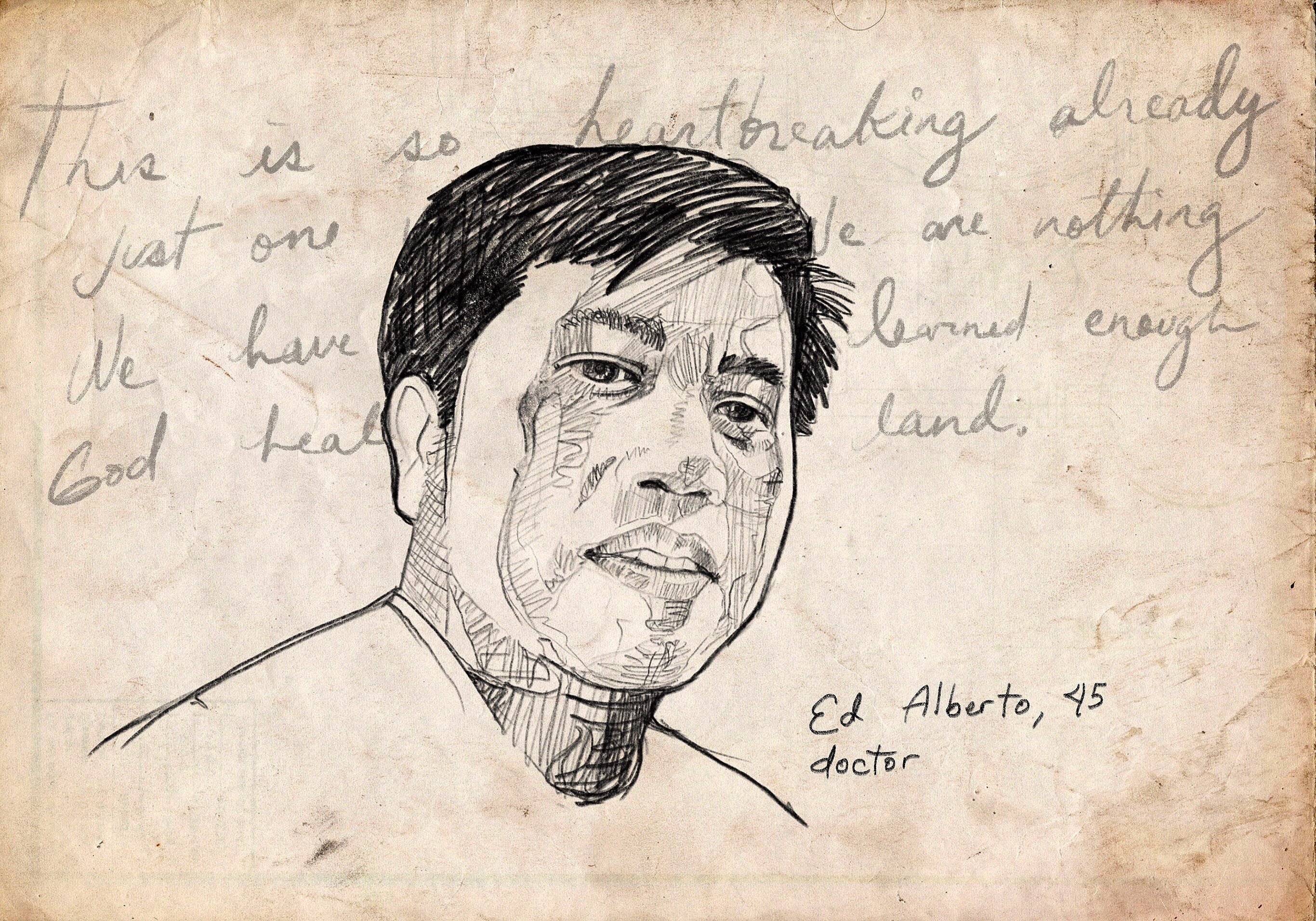

His name is Edison Alberto, and he is a doctor too.

‘Scared? We have to be scared’

Ed is a pediatric consultant who works for the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM), the country’s main novel coronavirus testing center. He is the head of RITM’s quality assurance office, in charge of ensuring all procedures, systems, staff and equipment are at par with international and national standards. He was for a time the hospital’s incident commander for COVID-19 operations.

Tina knows little of the internal processes of RITM’s COVID-19 response. Ed does not discuss his job, and she doesn’t ask. He is a stickler for confidentiality. What happens in the workplace stays in the workplace. One Saturday, halfway through the quarantine, it is Ed who steps into his exhausted wife’s place at the Cavite clinic.

This is how Tina describes her husband. Her Ed is a man of science. Ed is chill. Ed is invincible. Ed never gives in to pressure, never panics, never loses his cool.

Lately it is more difficult to remain unruffled, even for the man who never loses his cool. His online posts are rare, but one day, he takes to Facebook. All this, he says, “is heartbreaking.” There have been many diseases, says Ed, but he has seen nothing like this in recent history – a single virus, ripping into the medical community, killing colleagues and friends.

Foremost in his mind is another doctor, on a ventilator, positive for COVID-19. Her name is Sally Gatchalian, president of the Philippine Pediatric Society, RITM assistant director, a teacher and friend to himself and his wife.

If it can happen to other doctors, it can happen to them, he says. “And we can’t turn our backs, even if we know that.” For Ed, it is a statement of fact. “We still have to do our jobs.”

Tina has explained the situation to their three small daughters. They know, for example, that were anything to happen to Tina or Ed, they are to head to their uncles and their grandparents, who will keep them safe.

In the evenings, just before he leaves the lab, Ed sanitizes his hands with Sterillium, an alcohol-based surgical hand disinfectant. He drives home. He decontaminates his phone and his car keys. He leaves his shoes outside the house – “to satisfy my wife.” He goes into the pool to soak in the chlorinated water, then heads straight to the bathroom for a thorough shower.

It is only after all this that he hugs his children.

‘Kailangan maging malinis’

Between patients, the clinic’s walls are scrubbed once an hour, sometimes more. Electric fans are sprayed with disinfectant. Air conditioners are shut down, blinds opened, sunlight allowed to pour in. What income there is during the quarantine – patients are allowed to pay with promissory notes – goes into staff salaries and the cost of sanitation.

Tina has taken to leaving a box outside the clinic. The box is for donations of masks and gowns for health workers at the Philippine General Hospital (PGH). Many of the nurses are her friends, people she has known since the days she was a young doctor at PGH. Some remain her patients.

On March 26, the day Dr. Sally Gatchailan died of COVID-19, the ninth Filipino doctor struck down by the virus, Tina sends a message. “Our numbers are dropping.”

She is aware the hospitals will be overwhelmed. If the frontlines break, more doctors will have to step into the breach. Tina has discussed this with her husband. They will answer if called. Because they have children, only one of them will volunteer. It will likely be Ed.

Here are Ed’s hopes. He hopes for an end to the pandemic. He hopes to source more protective gear for technicians in the labs. He hopes someday his daughters will want to become doctors. He suspects one of them will.

Here are Tina’s hopes. She hopes the box of donations will fill. She hopes enough time is bought for a vaccine. She is certain she and her husband will be infected, but her hope is that their cases will be mild – enough that they can go back to work.

Here are Twinee’s hopes. She hopes her parents stay safe. She hopes to stay on duty. She hopes to grow old with the boy she met in a bus.

Here are Rowel’s hopes. He hopes to buy at least two more cans of sardines. He hopes to go back to school. He wants to be a medical technician, to earn more for his family and still stand shoulder to shoulder on the frontlines with his friends. And while he knows it might never happen, he’ll do the job that he has now, and he will do it well.

Here is a message from a frontliner working in a community clinic in Mambog I, Bacoor City.

He would like everyone to know that under his watch, all thirty-nine of his walls will stay clean. They will be sprayed, top to bottom, and wiped down three times: wet, damp, and dry. – Rappler.com

Editor’s note: All quotations have been translated to English.

Geloy Maligaya Concepcion is a visual artist, whose work can be found on Instagram under @geloyconcepcion. Journalist Patricia Evangelista can be contacted at pat.evangelista@rappler.com

Click this link for a list of donation drives for healthcare workers and frontliners during the coronavirus pandemic. PGH’s official site also contains links for assistance.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.