SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The roughly 200,000 people of Legazpi City, Albay, understand danger. All their lives, they’ve been under threat from Mayon, the country’s most active volcano.

They’re also on the so-called typhoon belt. Perched on the archipelago’s eastern flank, Legazpi and the rest of the Bicol region often face cyclones at their full strength, fresh out of the Pacific Ocean.

“Zero casualty” is Legazpi’s battlecry ahead of every disaster, and a badge of honor they have earned fairly often.

But the novel coronavirus is unlike typhoons or erupting volcanoes. Mayor Noel Rosal had to film himself explaining in the vernacular just how aggressive and deadly this new virus could be, and then deployed trucks with TV sets on the back to every neighborhood so the people could hear it straight from him.

He was especially worried for people in the slums, who might not have other sources of information on the pandemic, and yet were particularly vulnerable to contagion because they live in close quarters.

“Talagang ’pinaintindi namin. Very effective because ’yung fear ’tsaka ’yung cooperation, nandiyan,” Rosal told Rappler. (We really made them understand. Very effective because it struck fear in them and made them cooperate.)

The first alarm

Along with the rest of Luzon, Legazpi City was placed on lockdown or enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) on March 17. There was no recorded case of the coronavirus in Legazpi or in the rest of the Bicol region then.

Legazpi promptly closed its borders. Movement into and out of the city was restricted. It had time to prepare in relative calm, unlike Metro Manila, where the number of cases was already on the rise.

But, days later, on March 21, the city had its first COVID-19 scare when news came from Manila that Joey Bautista, vocalist of the band Mulatto, died of the disease on March 19. He had stayed at a hotel in Legazpi, where his band performed on March 11 – before the lockdown. The man was too sick to sing that evening, and had to bow out.

“Nataranta talaga lahat kasi party ’yon, siyempre marami na-expose,” Rosal said. (Everyone was frazzled because that was a party, so of course many were exposed.)

But a system was already in place, the mayor added. The local government’s Emergency Quick Response Team (EQRT), the police, and the fire bureau immediately set about tracing the people who had been at the party or had checked in at the hotel.

Contact tracers located people who had been at the airport and taken the same flights as Bautista, and even the employees of the party’s caterer from Naga City. The contacts were “seriously advised” to go into self-quarantine.

At the time, testing equipment were in short supply in the country, and Rosal formed a task force to source rapid test kits or coordinate with the Department of Health for swab tests, which then had to be processed at the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine in Muntinlupa City.

First case, immediate lockdown

Legazpi’s first COVID-19 case was an American man who tested positive on March 31. That evening, the police, fire bureau, and EQRT came to the man’s house to take him and his partner to the Bicol Regional Training and Teaching Hospital within the city for treatment.

The patient’s barangay and the one next to it were immediately put on hard lockdown. There was no resistance from the communities, Rosal said, because they had been warned, and they are used to the local government imposing hard measures during calamities.

Legazpi’s policy is, once a person tests positive for the virus, their barangay is immediately placed on lockdown to minimize movement. Then the EQRT, local police, fire, and jail management bureaus move in right away for contact tracing.

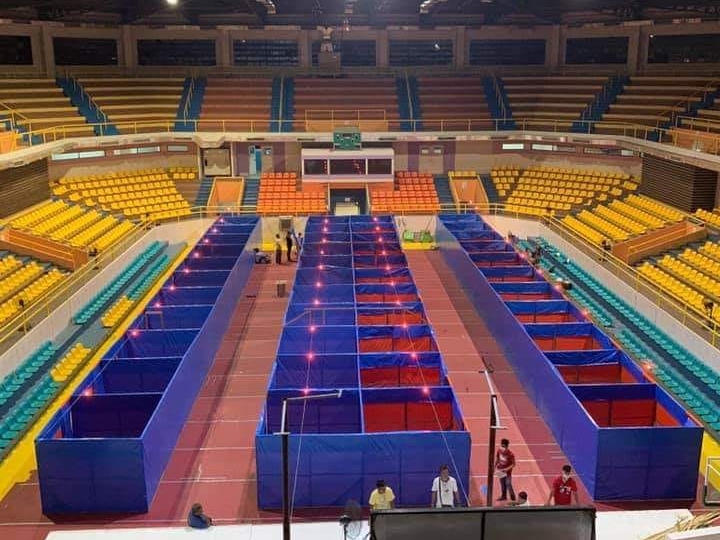

Earlier on March 31, Mayor Rosal announced that the city’s 8,000-seater stadium, the Ibalong Centrum for Recreation (ICR), had been converted into an isolation area for suspect and probable coronavirus cases.

‘Housemates’

The city began isolating contacts of virus patients at the ICR stadium on April 2, around the time the national government announced plans to convert stadiums and large halls in Metro Manila into quarantine facilities.

Isolating potential carriers of the virus as quickly as possible was crucial if the city was to be spared from a massive outbreak, Rosal said.

“’Pag ikaw suspect o probable, ’nilalagay na namin sa isolation…kailangan i-isolate na. ’Wag na natin patagalin. Kahit pa ’yan isang daan, kailangan i-isolate natin – may isolation area,” he added.

(If you’re a suspect or probable case, we put you in isolation right away…we need to isolate right away. Let’s not hesitate. Even if there’s a hundred of them, we have to isolate them – there has to be an isolation area.)

Every contact traced from confirmed patients was separated even from their family and brought straight to the ICR.

It may have seemed a little cruel, but it was effective, the mayor said.

To make up for the trouble, the Legazpi City government tried to make the ICR facility as livable as possible, calling it the “ICR Home Quarantine Facility.” The interned are called “housemates.”

“Ang pinakamahalaga pa dito, ’yung isolation area natin, dapat kumpleto tayo: pagkain, dapat may wifi, at saka siyempre dapat may libangan ’yung mga tao kasi mabo-bore talaga ’yan doon,” Rosal said.

(The most important thing here is our isolation area should be complete: food, it’s got to have wifi, and of course there should be entertainment, otherwise people there will really get bored.)

And it shouldn’t get overcrowded. The ICR has yet to reach full capacity, but the local government already converted a portion of the Legazpi City High School into another isolation facility.

“Just in case the cases spike,” Rosal said.

Isolate or else

The people were cooperative, Rosal said, but, to be sure, the local government warned them that it would impose fines on any suspect or probable case who refuses to be taken to the isolation facility.

When people are traced to have been exposed to confirmed COVID-19 cases, they get a written notification from the City Health Officer, delivered by the barangay captain. They are given a maximum of 6 hours to coordinate their transfer to the ICR.

Both symptomatic and asymptomatic close contacts are to stay at the “ICR Home Quarantine Facility” until their swab test yields a negative result, and they have been quarantined for 14 days.

Applying Republic Act 11332 or the Law on Reporting of Communicable Diseases, the city announced it would fine violators P20,000 to P50,000 or jail them for a month, or both, if they refused to cooperate.

Machines for COVID-19 testing

Of course, aggressive contact tracing is no use without aggressive testing for the virus. The Legazpi government decided it would not depend on the national government for that.

In the second week of April, the city government bought its own machines for COVID-19 testing: an automatic DNA extraction machine worth P3.9 million, and two polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machines worth P2.7 million each. The local government spent roughy P10 million to ramp up its testing capacity, to include the machines and the test kits.

The machines were delivered to the city by the end of April. Now, Legazpi can test up to 600 people for the coronavirus every day, but, so far, it has only needed to do an average of 200 to 300 tests daily.

As of Saturday, June 27, Legazpi City has had 33 confirmed COVID-19 cases, with one death and 30 recoveries. Two cases remain active.

“Hindi naman kailangan tayo mag-mass testing sa tingin ko sa ngayon, kasi nag-lockdown na kami ng almost 3 months. Kung may mga sakit talaga sa amin, talagang lalabas na ngayon ‘yan,” Mayor Rosal told Rappler.

(I don’t think we need to do mass testing at the moment because we had been on lockdown for almost 3 months. If any of us are actually sick, it would have been apparent by now.)

Corner markets

The city’s efforts were successful enough that, Rosal said, they only had one major cluster of local transmissions – at Victory Village North, a coastal slum community with a population of about 3,000.

It was what the mayor had feared – the virus reaching a congested community.

When it reported its first confirmed case in early May, the barangay was placed on hard lockdown. All access points were closed off and guarded by personnel in protective gear.

Residents were told to stay indoors, except to receive their food rations. During the lockdown, the Legazpi government provided households a bag of grocery items every 5 days.

That’s the secret, Rosal said: provide for the people you’ve put on lockdown, and they will gladly abide by it.

“Number one, ang importante the local government should be felt. Dapat maramdaman ’yung presensiya. ’Pag nag-lockdown ka ’tapos pinabayaan mo, ’wag ka na,” the mayor said.

(Number one, what’s important is the local government should be felt. People should feel the presence. If you lock them down and then abandon them, better begone.)

When the local government put the first two barangays on lockdown on March 31, it prepared tables in open areas with fresh food and produce for the residents in quarantine, with sellers in full personal protective equipment.

Because it took 10 days of lockdown to contact-trace both barangays, local officials set up little corner markets for residents so they didn’t have to leave their neighborhoods to get food. They were given relief bags, but who wants to eat canned goods for 10 straight days?

As for Victory Village North, the local outbreak stopped at 7 confirmed cases. On May 16, the local government lifted the lockdown, except in one neighborhood, which had to stay indoors a few more days.

Typhoon Ambo

On May 15, as the city was preparing to ease into general community quarantine (GCQ), the year’s first cyclone, Typhoon Ambo, battered the Bicol region, including Legazpi.

Across the region, some 140,000 people were forced to evacuate. Enforcing social distancing at evacuation centers was tricky. The national government recommended separating families within the schoolhouses and public halls they sheltered in, using tents if they were available.

Although Ambo was pretty strong, it caused minimal damage to Legazpi and left no fatalities. The local government had to ration out more food because people stayed indoors, but the city was virtually unscathed.

Equilibrium

Ever hardy, Legazpi residents nimbly adjusted to the rules and protocols for the pandemic, Mayor Rosal said.

During ECQ and even when the city transitioned to GCQ in mid-May, the city had a daily curfew from 8 pm to 4 am. It went on even as the city eased into modified GCQ on June 1.

To allow for a little more economic activity, the city council shortened the curfew hours to 10:30 pm to 4 am starting June 26.

To prevent people from congregating at markets and grocery stores, the local government divided the city’s 70 barangays into 4 clusters, and assigned them shopping hours.

Each cluster had half a day, every other day, to buy food and necessities, and to run errands. During ECQ, only one household member was issued a quarantine pass and allowed outdoors.

Reliable government assistance combined with rigid but feasible schedules for outdoor activities gave Legazpi City a kind of equilibrium during the months on lockdown.

Although the people of Legazpi are used to adjusting to force majeure, the local government knew it needed sensible policies that people can realistically follow, Rosal said.

“First, you need to have a system in place. Then number two is the maturity of the people,” the mayor added.

Homecomers

What threatened to upset that balance was the influx of people from Metro Manila – the epicenter of the pandemic in the country – coming home to Legazpi when the capital region eased into GCQ on June 1.

“Ako, akuin ko, medyo nagkaproblema, pero mga kababayan namin ’yan. So gumawa kami ng sistema. Dahil wala kami masyadong cases, sila pinagtuunan namin,” said Mayor Rosal.

(I’ll admit it, there was a bit of a problem, but they’re our people. So we created a system. Because we didn’t have a lot of [local] cases, we focused on them.)

On May 29, Rosal released guidelines on how the city would handle the returnees.

First, as the national government ordered, Legazpi was not to deny entry to stranded persons and returning overseas Filipinos who had the complete set of requirements, such as proof of residence and health clearances.

Still, all homecomers were to go straight to the ICR isolation facility upon arrival for COVID-19 testing. They were prohibited from heading home until they tested negative.

Those who tested positive were brought immediately to the Bicol Regional Training and Teaching Hospital (BRTTH). Those who turned out negative for the virus were allowed to go home, but under regular monitoring by barangay health emergency response teams.

On June 23, a 56-year-old man who had just flown into Legazpi from Metro Manila tested positive for the coronavirus. He had been allowed to go home after his swab sample was taken because he was an “authorized person outside residence,” and the national task force’s rules exempted him from mandatory facility quarantine. Besides, he was staying alone in his Legazpi apartment, Rosal said.

But it was a close call. After that, the city government put its foot down: no exemptions – anyone entering the city would be quarantined at the ICR stadium until they tested clear of the coronavirus.

‘Don’t wait for the national government’

So whether they arrive by land, sea, or air, all people trying to get into Legazpi have to be tested at the ICR stadium. First, a rapid test, and if it yields a negative result, the person may go on home quarantine for 14 days.

If they test positive, they are given a confirmatory swab test, and must remain at the ICR facility until the result comes out. If it’s negative, then they may go home. Otherwise, they are brought to the BRTTH.

Legazpi has so far welcomed around 300 arrivals, of whom two tested positive. They were asymptomatic.

“Kung nakauwi ’yon, hindi lang sa pamilya, pati sa barangay nakipag-inuman na sana ’yon doon,” the mayor said, relieved that they were able to intercept and quarantine both patients.

(Had they gone home, then would have already gone drinking not just with their families but their entire barangays.)

“’Tiyagaan kahit magastos. Bumili kami ng rapid test, may testing machine kami, kumpleto,” he added. (Do it even if it’s costly. We bought rapid test kits, we have testing machines, everything.)

You need to have both the right programs and the necessary facilities, the mayor said. “Hindi na dapat maghintay sa national government (You shouldn’t wait for the national government).” – Rappler.com

TOP PHOTO: CITY LIGHTS. Legazpi City during one of Mayon Volcano’s recent eruptions. Photo by Rhaydz Barcia/Rappler

OTHER STORIES IN THE ‘PEOPLE VS PANDEMIC’ SERIES:

- In the fight vs COVID-19, these women mayors didn’t take chances

- Valenzuela City’s pandemic response: ‘Everything has to happen now’

- In Baguio, Magalong returns as top investigator – for coronavirus contact tracing

- How Iloilo City became ‘Wakanda’ of the Philippines

- ‘Common sense’ and speed shield Marikina City from the coronavirus

- In Pasig, fighting corruption yields cash aid for the people

- How to fight the pandemic: Women mayors don’t sugarcoat how deadly the virus is

BOOKMARK THIS TO HAVE THE LINKS TO THE STORIES IN ONE PAGE:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.