SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE

- After a downward trend for unemployment since 2005 and a 14-year-low rate in October 2019, the coronavirus pandemic caused unemployment to shoot to a record-high 17.7% in April 2020, more than triple the unemployment rate in April 2019. This means almost 1 in every 5 persons in the labor force are unemployed.

- Economists say the actual number of jobless persons may be much higher, accounting for those excluded from the labor force as well as potential entrants who were hindered by the lockdown.

- For employment recovery, economists urge the government to support the agricultural sector and others with job-supporting potential, provide aid to workers and businesses, and adapt the Build, Build, Build program to strengthen pandemic resilience.

MANILA, Philippines – The coronavirus pandemic caused the highest unemployment rate in the country on record, leaving around 7.3 million Filipinos jobless.

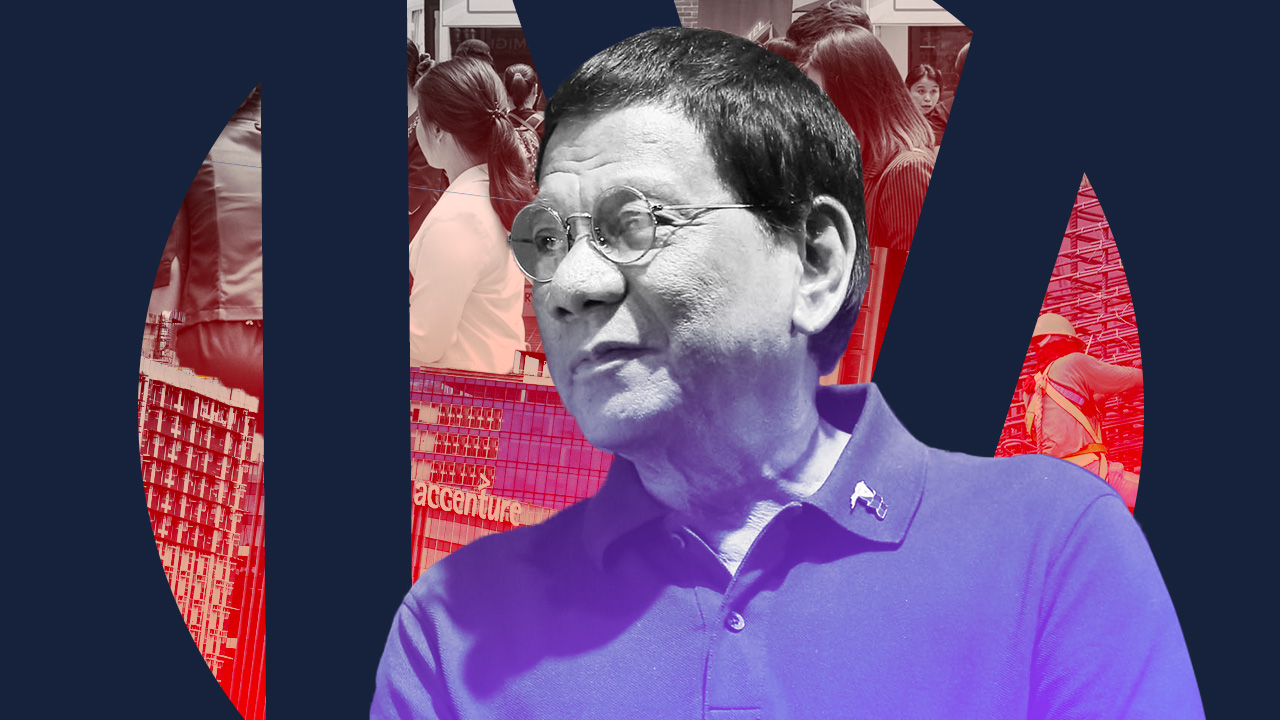

The virus outbreak offset the 14-year-low unemployment and underemployment rates achieved in the first half of President Rodrigo Duterte’s 4th year in office, particularly in October 2019. The unemployment rate decreased from 5.4% in July 2019 to 4.5% in October 2019, the lowest across all quarters since 2005.

COVID-19 causes exponential unemployment increase

The coronavirus outbreak caused the unemployment rate to spike to 17.7% in April 2020, the highest unemployment rate since the earliest comparable data in 2005, based on the preliminary results of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). This is more than triple the 5.1% unemployment rate recorded in April 2019.

The 17.7% unemployment rate, close to 20%, means that around 1 in every 5 persons in the labor force is unemployed, confirmed economist JC Punongbayan in a phone interview.

The April 2020 unemployment rate is unprecedented in decades. From 1976 to 1986, under the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, there were no double-digit unemployment rates recorded.

According to national statistician Dennis Mapa, the next highest unemployment rate was recorded in the second quarter of 1991 at 14.4%. Punongbayan said that the early 1990s saw a recession largely because of the power crisis, which caused a severe reduction in productivity.

Meanwhile, the last recorded double-digit unemployment rate was in January 2005 at 11.3%. According to the PSA, the dip in employment at the time may be attributed to the oil price surge and inflation rate uptrend in the preceding months.

However, these figures were not comparable to the current rates since the PSA revised its unemployment metrics in April 2005. The new definition of unemployed people include those who are 15 years old and over and were without work, currently available for work, and were either looking for a job or not looking due the following reasons: tired/believed no work available, awaiting results of previous job application, temporary illness/disability, bad weather, and waiting for rehire/job recall.

The old definition of unemployment persons only included those without work and are looking for work or those without work but are not looking for work because of valid reasons. IBON Foundation said the change in unemployment metrics lowered official reported unemployed Filipinos.

Using the current metrics, the next highest unemployment rate was recorded in April 2005 at 8.3%, more than half of the April 2020 rate. Punongbayan said the April 2005 rate may not be considered unusual, since it was part of the downward trend in unemployment.

He said the closest economic downturn before the pandemic was the 1998 recession or the Asian financial crisis. Even during the 2008 and 2009 global financial crisis, Punongbayan said the economy did not contract, reflecting the “resilience and robustness” of the Philippine economy. (READ: [ANALYSIS] Rare Philippine recession: Why this one’s unique, even necessary)

Across the regions, the PSA April 2020 Labor Force Survey showed that the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao had the highest unemployment rate at 29.8%, followed by Central Luzon at 27.3%, then the Cordillera Administrative Region at 25.3%.

Economist AJ Montesa of the Action for Economic Reforms said that the “stay-at-home orders” or the levels of community quarantine imposed as a measure to contain the virus was the most apparent unemployment factor. Most businesses and companies needed to adopt work-from-home arrangements, but only a fraction of workers were capable of working from home.

“Businesses such as retail stores and restaurants usually employ ‘no work, no pay’ schemes for their employees, and because there could be no way these employees could go to work, they were essentially out of the job,” Montesa said in an email interview.

He added that consumer demand also fell dramatically, forcing businesses to resort to layoffs to stay afloat or due to bankruptcy.

Meanwhile, the underemployment rate also increased from 13.4% in April 2019 to 18.9% in April 2020. According to Montesa, many businesses may likely be unable to afford keeping their employees at full-time capacities, if at all. Thus, many workers ended up working a reduced number of days per week and/or a reduced number of hours per day.

Before pandemic, unemployment on a downward trend

Montesa said that the unemployment rate in the Philippines had been on a downward trend since 2005, which was driven primarily by the “sustained period of strong economic growth” experienced by the country.

“This period of sustained economic growth would allow for an environment of high consumer and high investor confidence producing job growth, leading to a declining unemployment rate,” Montesa said.

In January 2020, the unemployment rate rose to 5.3%, as estimated by the PSA. This was also correlated with the gross domestic product (GDP) growth decline in the first quarter of the year, Montesa said.

The 2019 annual GDP growth rate at 5.9% was the lowest since 2011, missing the government’s 6% to 6.5% target range. Economists said there were weaknesses in farm output and trade, and economic growth was hindered by a slowdown in investments and industry growth. (READ: Coronavirus drives Philippines toward recession as Duterte’s 4th year ends)

As to the impact of the Build, Build, Build program, Montesa pointed out that the number of construction workers increased from 3.5 million in July 2016 to 4.22 million in October 2019, resulting in a net job creation of around 720,000 jobs or 32.8% of new jobs created in that period.

He said that while the sharp increase in construction jobs came in the last few months of former president Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III’s term, the Duterte administration managed to continue ramping up the sector. However, many projects lagged behind, possibly weakening job growth.

Unemployment rates don’t present full picture

According to a policy brief of Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU) economics professor Geoffrey Ducanes, the unemployment rate does not present the whole picture. While the number of unemployed persons rose by around 5 million, the number of employed persons declined by nearly 8 million, relative to April 2019.

The employed and unemployed comprise the labor force. Ducanes said the difference of 3 million was counted as those not part of the labor force – which increased by around 5 million in a year – likely because they reported that they were unavailable for work due to the lockdown or coronavirus fears.

Ducanes presumed a much higher number of unemployed persons that “could easily reach 15 million,” since there would have been new entrants to the labor force if it had not been for the lockdown, and some had jobs but did not earn income because they were unable to work.

He said that employees who are paid per day, per hour, per piece of output, “pakyawan,” or on commission basis, make up for over 60% of employees.

Meanwhile, IBON Foundation estimated the real unemployment rate to be around 22% and the real number of unemployed around 14 million. The organization said that the current definition of unemployment excluded up to 4.1 million Filipinos who did not formally enter the labor force due to the enhanced community quarantine and another 2.6 million whom the revised unemployment metrics stopped counting.

What sectors are most affected?

In the latter half of 2019, employed persons in the services sector were consistently the highest group at 57.8% in July 2019 and 57.7% in October 2019. For both quarters, workers in wholesale and retail trade and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles were the largest percentage in the services sector.

Montesa said that while all sectors had lower figures for employed persons, the most affected sectors were wholesale and retail trade, construction, transportation and storage, manufacturing, and accommodation and food services, since these seemed to have suffered the biggest reduction of workers.

Further, subsectors with the largest drop in employment were arts, entertainment, and recreation with a -54% change, electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply with -43.1% change, and information and communication with -40.6% change.

Ducanes wrote that approximately half of those employed in wholesale and retail trade and repair of motor vehicles, construction, and transportation and storage belong to the poorest 50% of households, meaning, “their income situation is precarious and they are vulnerable to any loss in income.”

While some sectors are more vulnerable than others due to the shift in employment opportunities and consumer choices, Montesa said, others are more secure. He added that compared to the pre-pandemic period, more workers are now in agriculture, public administration and administrative services, and education.

However, measures to contain the virus may cause a different reality on the ground. For instance, local quarantine protocols hinder farmers from sustaining their livelihood, according to their experiences under lockdown. In the Mountain Province, farmers found it difficult to sell mounds of vegetables and crops due to strict and inconsistent checkpoint rules. (READ: Farmers trash spoiled vegetables while poor go hungry)

Meanwhile, in the province of Quezon, some farmers were told that they could no longer leave their homes nor till their land. These farmers estimate losses from P57,000 to P60,000 due to the wilted crops. (READ: Coronavirus lockdown pushes farmers, fisherfolk into deeper poverty)

The informal sector, on the other hand, is also more at risk due to a lack of social protection. Informal economy workers include independent, self-employed, small-scale producers and distributors of goods and services, as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

While they made up 38% of employed persons or 15.6 million as of 2017, only around 962,000 informal workers were set to benefit from the Department of Labor and Employment’s regular Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa Ating Disadvantaged/Displaced Workers (TUPAD) program as of May 10.

Worldwide, ILO said that over two billion of the 3.3-billion global workforce were part of the informal economy, and around 1.6 billion of these informal workers were at risk of “massive damage” to their means of living in the second quarter of 2020. (READ: Half of world’s workers risk livelihoods being ‘destroyed’ – ILO)

In addressing the needs of informal workers, the UP COVID-19 Pandemic Response Team recommended that their inclusion in the emergency subsidy program be ensured, that TUPAD and other cash for work programs be expanded, and that food and cash transfers to indigent households continue to be provided, among others.

What should be done for employment recovery?

In reviving the economy amid the pandemic, economists said that recovery should prioritize essential sectors and pandemic resilience. In another policy brief, ADMU economics educators Jerik Cruz and Marjorie Muyrong identified sectors, based on projected employment impacts of investments, with the most “job-supporting potential,” including agricultural sectors, construction, health services, land transportation, and wearing apparel.

Montesa also believed that it would be a good opportunity to support the agriculture sector, which would entail providing more in terms of infrastructure investment, training and education, technological capacity building, subsidies and loans, and cash transfers.

He also said that local micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) will suffer due to “slow, if not practically zero, business” and will not be able to keep employees on payroll. (READ: ‘Sariling diskarte’: The heavy impact of lockdown on micro, small businesses)

“The government can provide zero-interest loans or even subsidies which would enable these smaller firms to keep their workers employed, at least until things stabilize,” Montesa said. He also urged the government to invest in physical and telecommunication infrastructure, to ensure safety and efficiency for those who go to work using public transportation as well as to enable businesses to implement distancing measures by providing reliable internet infrastructure.

Education and the entertainment sector must also be prioritized, Punongbayan said, because they were also hardest hit in terms of job losses.

For Punongbayan, the DOLE has not spent “nearly enough” on emergency employment programs and financial aid for workers. He said the department should be allocating more funds that approximate the billions of pesos being eyed for wage subsidies under the Accelerated Recovery and Investments Stimulus for the Economy of the Philippines bill.

Besides wage subsidies, government, according to Punongbayan, should also provide unemployment insurance, zero interest loans, and other measures that could help people survive during the crisis.

What are the government’s plans for increasing employment opportunities? For one, Build, Build, Build projects will be evaluated and prioritized based on their potential impact on the economy.

Cruz and Muyrong recommended that the Build, Build, Build program be adapted for strengthening pandemic resilience by focusing on the development of social, digital, and rural infrastructure. According to them, these will minimize inequalities in accessing digital technologies/opportunities and maximize agricultural productivity and food supply, respectively, during the global crisis.

The House of Representatives has also approved bills for stimulus packages that will offer assistance to MSMEs and other affected key sectors, as well as fund infrastructure projects in rural areas, among others. However, since Congress has adjourned sine die, these bills may take time to be enacted.

In the meantime, Montesa said that reopening the economy to some degree is necessary to boost employment, but he cautioned that the administration must balance the need for economic activity and the need to prevent a virus outbreak.

“As of now, Metro Manila is poised to slowly re-open its local economy, but things could change in as quickly as a few days, so our policy-makers must be very careful, sensitive, and adaptive to changing conditions,” Montesa said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.