SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

It was one of the last letters that Dandy Miguel would receive – a notice on September 3, 2020, that his company, Fuji Electric in Calamba, Laguna, would take their union to arbitration for the work stoppage they caused the month before to force the creation of COVID-19 guidelines in the workplace.

“Such malicious and false statements against the company would also be subject to administrative cases under the company’s rules and regulations,” the letter said. It was addressed to Miguel, as the union president, and the rest of the board directors of the Lakas ng Nagkakaisang Manggagawa sa Fuji Electric Philippines (LNMFEP).

The issue led to hearings at the National Conciliation and Mediation Board (NCMB), but the government could not mediate and left it to the company and the union to settle.

In the end, the union bargained away some benefits, such as seniority pay and birthday leave, so the company would withdraw its suit, according to Aries Castillo, the union’s vice president.

The good thing is that the union was able to keep most of the major provisions in their collective bargaining agreement (CBA) finalized in December 2020, said Castillo.

In the CBA, all regular rank-and-file employees would get an increase of as much as P50 per day by 2022.

It was Miguel’s last victory lap for the union.

Then he was shot dead by still unidentified gunmen on March 29, 2021, making him the 10th activist to be killed in the Calabarzon region that month alone.

According to rights group Karapatan, 230 human rights defenders have been killed since the time of President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016. Of that number, 135 are from different groups of farmers, fisherfolks, and laborers. There were five killings within the ranks of Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU).

Besieged by pandemic

Fuji’s work stoppage was prompted when one of the workers tested positive for the coronavirus on August 14, 2020, and the union said there wasn’t a clear guideline on how the workplace would be disinfected and how a 24-hour lockdown was going to be implemented pursuant to government rules.

By August 15, workers had gone on mass leave. It was easy to convince otherwise hesitant laborers, said Castillo.

“Madali naman kaming nakapag-mass leave kasi siyempre takot rin sila sa virus,” Castillo said in an interview with Rappler. (We were able to stage a mass leave because workers were scared of the virus.)

Fuji insisted “there was no existence of imminent danger which would excuse any employee from absenting himself from work,” and claimed that the three-day work stoppage cost the company $1.5 million.

The issues were settled and all was worked out, except for one thing: “‘Yun lang, nawala ang aming pangulo (We lost our president),” Castillo said, referring to Miguel’s murder in March.

Edgar Hilaga of Olalia-KMU said that, in another company in Laguna, they weren’t able to get the government’s financial aid from the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) at the start of the pandemic.

“Hindi raw kami qualified dahil ang category daw namin ay large-scale enterprise,” Hilaga said. (We were told we weren’t qualified because we were a large-scale enterprise.)

There were rumblings at the start of the pandemic that DOLE was only prioritizing small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

“Pero, one time, nagpunta ako ng provincial office ng DOLE, tinanong ko kung merong application ang aming kumpanya, pero ang representative na humarap sa akin ang sabi walang finile na application,” said Hilaga.

(But when I went to the DOLE’s provincial office to ask if our company filed an application, the representative I talked to told me no application was filed.)

Government systems discouraging

Fuji’s notice to explain for the work stoppage was handled by a union prepared for the consequences. Not all notices are managed that way.

The routine explanation slip, or “ES,” is feared by laborers because it could easily mean firing by the agency that outsourced them. Contractualization thrives in the Philippines because of third-party agencies, which act as outsourcing middlemen, shielding corporations from legal obligations such as regularization and statutory benefits.

According to data from KMU, there are 3.9 million jobless Filipinos as of January 2021. The group said 1 in every 2 companies implemented layoffs, such that 9 in every 10 contractual workers lost their jobs amid the pandemic. The group added 4 in every 10 workers are still under “no work no pay” status.

The unionists that Rappler talked to said workers would rather show up for duty on rest days than answer an ES. Most of them have a four-day workweek, with 12-hour daily shifts. But, according to them, companies have a habit of putting a schedule on a rest day.

It’s paid, but it also compromises the health of an exhausted laborer.

“Kapag ikaw ay nabigyan ng ES, bibilangan ka na hanggang sa ikaw ay matanggal (If you’re given an ES, it’s like a ticking clock until you are fired),” said Maricel*, a union leader from Laguna who requested to be kept unnamed as she had been recently red-tagged and surveilled.

“For a worker who earns P376, not being able to earn for a day has a big impact. More so when you’re fired,” she added in Filipino.

It’s not like the government channels for labor arbitrations are encouraging, said Hilaga, especially when it comes to the National Labor Relations Commission, which he called “one of the most difficult resorts.” The NLRC resolves labor and management disputes.

“If you look at the processes of NLRC and DOLE, they have so many rules before you can file. The mediation goes in circles before you’re allowed to file a formal case. And, once it’s filed, there comes the burden of a very slow pace. Not only is it slow, we also end up losing,” Hilaga said in Filipino.

In the Philippines, five years to resolve a dispute is already very fast. After the NLRC, it usually goes to the Court of Appeals and reaches the Supreme Court before any concrete remedies are made. In many cases, the win settles to just be a moral victory, a hope that a precedent will make it better for the next generation of workers.

The system also seems designed to keep workers stuck in their ranks, as Maricel said she had never known a laborer who was able to become a top management employee.

Relating to the workers of Tanduay who staged a strike to call for regularization in 2015, Paul Carson, spokesperson of Pamantik-KMU said in Filipino: “I can’t say that they’ve surrendered to that fate, but there is not much option or opportunity for workers, especially those without a union, to move up the ladder.”

Sa kasaysayan, ang tanging sinasandalan ng manggagawa bilang kakampi ay sarili niya.

Edgar Hilaga, Unionist

How to be a unionist

Maricel is a graduate of a vocational course. She started in the factory as a machine operator when she was 19 years old. Twenty-two years later, she leads the union as they battle a record-high hesitancy among laborers to join because of intense red-tagging.

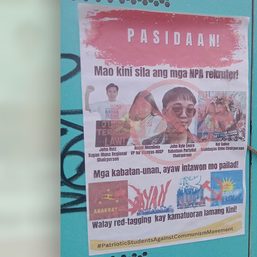

Recently, a poster red-tagging their union was spotted outside their industrial zone, and some of their members were subjected to house-to-house surveillance by men claiming to be state agents.

Maricel is now versed in the game of propaganda. She said her company routinely holds orientations for workers, convincing them that the same benefits are within reach even if they are not union members.

“Ito pong huling limang taon, nagkaroon kami ng problema sa pagpapasapi sa unyon mula nang napalitan ang aming HR manager. Ang naging taktika nila, may black prop sila sa pagsapi sa unyon. Nire-redtag na nga kami, kaya paparami ang hindi sumasapi sa unyon,” said Maricel.

(These last five years, we’ve had difficulty recruiting to our union since we had a new human resources manager. Their tactic is to spread black propaganda against the union. We are red-tagged, so there are more people who do not join the union.)

“Memberships tick up only when it’s time for the CBA and the officers are also able to do their own propaganda,” she added.

Hilaga said there was a time before the Duterte administration when they enjoyed a fruitful and productive relationship with the government because the regional labor director was pro-worker. As they harvested increasing wins, the director was reassigned, and the animosity returned.

Unionism is also a game of looking for and nurturing allies from management or from the government. Otherwise, it’s a steep hill.

“Pana-panahon, may mga nauupo sa posisyon na may kaparehong prinsipyo sa manggagawa at makamamamayan ang prinsipyo, pero, sa kasaysayan, ang tanging sinasandalan ng manggagawa bilang kakampi ay sarili niya,” said Hilaga.

(There are seasons when the person in power has the same principles as the workers, has a pro-people principle, but, based on history, unionists only have themselves to rely on.)

Maricel still fears for her safety, both from red-tagging and from the coronavirus, as she has already survived COVID-19 twice.

She says in the best times, and especially the worst times, the union had her back. It is a war they have always fought alone.

“Kung ano man ang mangyari sa akin at sa pamilya ko, walang bukas palad na tutulong kundi ang aking mga kapwa member sa unyon,” said Maricel. (Whatever happens to me and my family, no one else is as open to helping as my fellow union members.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] Jhed and Jonila’s fight for justice](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/TL-jhed-and-jonilla.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=411px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.