SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Aetas Japer Gurung, 30, and Junior Ramos, 19, both can’t read nor write. They planted taro and corn in their ancestral mountainous village in San Marcelino, Zambales.

They are supposed terrorists now facing life imprisonment, also the first to be charged under the feared anti-terror law.

Their wives, both minors, are in jail, too, for illegal possession of firearms and explosives.

The military accuses them of shooting a soldier dead in an encounter with the 73rd Division Reconnaissance company of the military’s 7th Infantry Division on August 21, 2020, for which they are on trial at the Olongapo City Regional Trial Court Branch 97.

Pleadings in the Supreme Court show that Japer and Junior claimed torture in the hands of army soldiers, who allegedly forced them to confess to being members of the New People’s Army (NPA). (The Armed Forces of the Philippines had denied this accusation.)

Until February 2, this had been the story. The National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) filed on that day Japer and Junior’s petition to intervene in the Supreme Court case seeking to void the anti-terror law

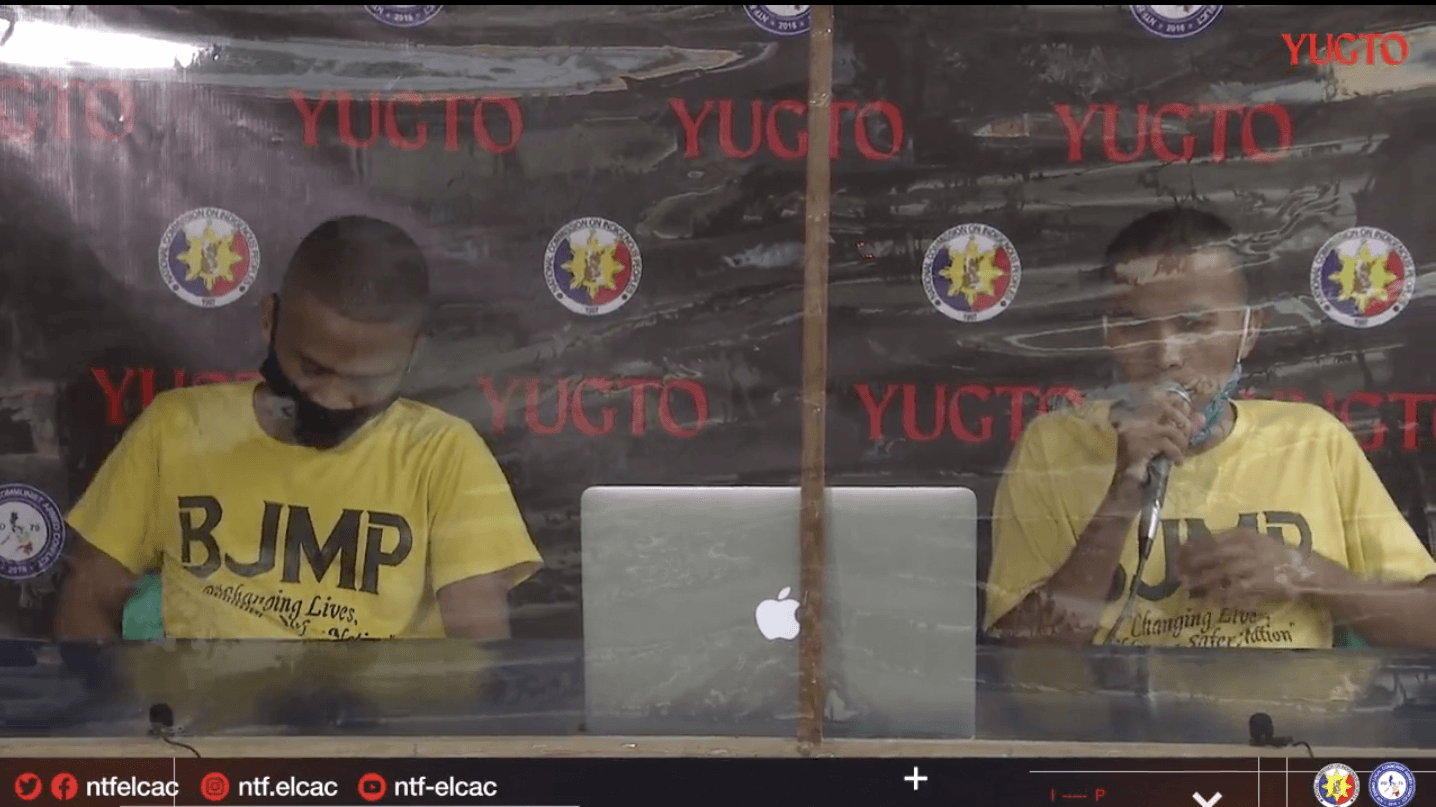

On Wednesday, February 10, Japer and Junior sat down at a table in jail, with a Macbook in front of them, poster behind, and then livestreamed by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC).

It was a day after Solicitor General Jose Calida had dropped his bombshell at the Supreme Court, disclosing that Japer and Junior were withdrawing their petition to intervene.

In the streamed press conference, Japer and Junior announced they were also dropping the progressive NUPL, and will be represented henceforth by the Public Attorney’s Office (PAO).

Distraught

“Hindi namin alam kung saan kami papanig dahil dala-dalawa ang gumagalaw. Pero naisipan namin ng bayaw ko, mas ano tayo sa PAO at NCIP dun na lang tayo, ipirmi na natin ang isip natin na doon na, baka sila ang tutulong sa atin para madali tayo makalaya,” said Japer.

(We don’t know who to side with because two groups are moving. But my brother-in-law and I decided that we would be better off with PAO and NCIP, we agreed to settle our minds on staying with them because they may be the ones who can help free us.)

Both were visibly distraught. The younger Junior spoke less. Japer choked up when host Mikaela Guerra said she’s opening the floor to media. They had been going on for 23 minutes at that point, answering questions from Guerra and Marlon Bosantog, director for legal affairs of the National Commission of Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

“Nahihiya po ako Ma’am, kinakabahan po (I’m shy, I’m nervous),” Japer said.

Bosantog then decided not to let media join in, saying “it would be improper.”

NTF-ELCAC Spokesperson Lorraine Badoy spoke next, promising that the Duterte government would want nothing less than for them to return to a quiet life in the mountains.

It is ironic because it’s the military which accused the Aetas of being communists.

“Yung gobyernong nagsasabing tutulungan sila, ‘yun ang mismong nagkulong sa kanila, ‘yun ang mismong dahilan kung bakit sila nandiyan sa kulungan,” said Bonifacio Cruz of the NUPL’s Central Luzon chapter. He had been representing the Aetas until they were cut loose.

(The government claiming to help them is the same government who jailed them, they’re the reason why they’re in prison.)

The NCIP and NTF-ELCAC have been longtime partners. Bosantog is also the spokesperson of the NTF-ELCAC’s legal cooperation cluster. He believes the anti-terror law is presumed to be constitutional, telling a webinar in June that tribal leaders are being killed by the NPA.

“There are realities on the ground that really are oppressive, and it’s horrifying. There is a certain kind of urgency and if you look at the anti-terrorism bill, it could also work as a tool to empower our law enforcement to go against terrorists,” Bosantog said.

Not NPA

Japer said they only know how to farm.

“Ang alam lang namin po nagtatanim lang kami ng gabi at palay, ngayon po dahil naiwan na po namin ang bundok namin, naisip na lang namin ang pagtatanim namin ng gabi at mais,” Japer said, near tears.

(All we know is how to plant taro and rice, but we’ve left that in the mountain, we could only think of our planting taro and corn.)

Giya Clemente of the group Umahon Central Luzon said Japer and Junior have no political background, no affiliations that can be red-tagged.

“Mga sibilyan lang sila na nataon lamang na sila ay nasa isang lugar at nasa isang panahon na wala na silang magagawa,” said Clemente, whose group engaged the help of the NUPL.

(They are just civilians who were caught in a place and a time where they can no longer do anything.)

Junior and family had just come from a gahak on August 21, 2020, when they heard bursts of gunfire, Junior said in his counter-affidavit submitted to Olongapo prosecutors in September 2020.

Gahak is an Aeta farming practice of cutting and burning trees as a way of clearing the area.

They decided to go back to their barrio, making sure to take with them their carabaos “because they were our only helper in the farm,” the affidavit read.

When they got to their house, there were military men who told them to stay as “it is safer for us to stay because accordingly, there are other military personnel running after fleeing NPA and scouring the area and that they might mis-include us.”

“Since it was lunchtime, my father ordered us to cook food after which all of us [ate] together with the army. Regrettably, and to our surprise, the soldiers informed us that they were arresting us because accordingly we are NPA fleeing,” Junior said in the counter-affidavit.

In this counter-affidavit, Junior said they were taken to another place and interrogated for 6 days. “They manhandled me, [fed] me with feces because of our continuous denial of any ties with NPA subject of their operation. But I admit that I am a surrenderee but they did not believe me.”

A bag of subversive documents and ammunition were seized from Junior and his family, but Junior claimed in the affidavit that their bag carried only clothes.

In the Supreme Court petition, Japer said that the army did not believe he wasn’t NPA because he didn’t speak Ilocano like the rest of the tribesmen. Japer said it’s because he is originally from Pampanga. Junior had lived in Sitio Lomibao since birth.

“Sabi ko, ‘Hindi po ako talaga, dati, NPA ako pero nagbagong-buhay na ako.’ Sabi ko sa kanila, pero hindi, talagang pinip–, talagang sinasaktan ako talaga,” Japer said, according to a transcript of an interview quoted by the NUPL in the Supreme Court petition.

(I said that I’m really not. Before, I was NPA but I’ve changed, but they didn’t, they really, they were really hurting me.)

Pitang Gurung, Japer’s mother, told Umahon Central Luzon that she didn’t know that her son is or was an NPA.

“All I know is that he was helping his mother-in-law in Zambales, and suddenly they’re saying he’s NPA,” Pitang said in her native language.

In his counter-affidavit, Junior said he “was a surrenderee sometime February 2020 and from then on I never joined them out of fear of being killed in retaliation.” But he also said in the same affidavit: “I was never a member of the NPA.”

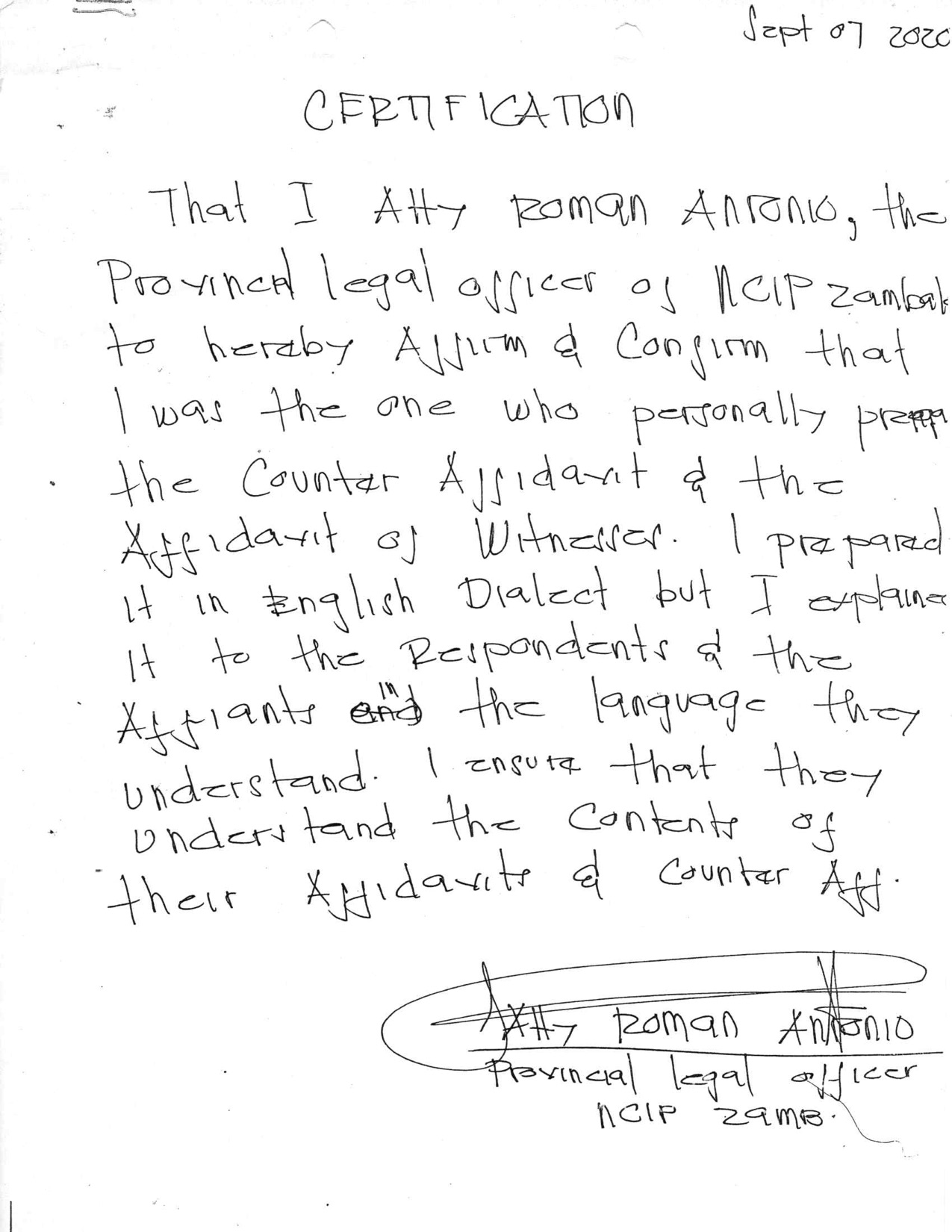

Cruz clarified that the September counter-affidavit was not prepared by NUPL but by the NCIP. Below is a certification by NCIP provincial legal officer Roman Antonio, saying he prepared the affidavit in English, but that the content was explained to Junior thoroughly.

The turnaround

In the NTF-ELCAC press conference, Japer and Junior affirmed Bosantog’s questions that they didn’t know what they were signing on to when the NUPL filed the petition for intervention.

“Parang sila po yung pabigat sa kaso na dinadala namin, kaya naisipan po namin na mag-ano na lang kami sa PAO at NCIP magpapa-abogado,” Junior said.

(It’s like they were making the situation worse, so we thought we would choose PAO and NCIP as our lawyers.)

“Naramdaman niyo po ba na parang ginamit nila kayo? Na parang inabuso nila ang karapatan ninyo?” Guerra asked. (Did you feel you were used? That they abused your rights?)

“Opo, ma’am (Yes Ma’am),” was Junior’s short answer.

When the press conference began, Guerra asked them to recall what happened on the day that the NUPL allegedly “forced” them to sign on to the petition for intervention. This turnaround was first revealed by Calida, whose Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) also lawyers for the NTF-ELCAC.

“Noong araw po na ‘yun gulong-gulo po kami ng bayaw ko, dahil hindi po namin alam, dahil noong araw na ‘yun, gulong-gulo ang isip namin na akala namin na ganun na lang po ‘yung, ‘yung pagka-ano namin sa kulungan, parang pinabayaan kami ng ano po, ng NUPL,” said Japer.

(On that day, my brother-in-law and I were so confused, because we didn’t know, because that day, our minds were so confused, we were thinking that we would just remain that way in prison, it’s like we were neglected by NUPL.)

Junior said something to Japer inaudible from the stream.

“Tapos po ‘nung pumirma na po, hindi po sana ako pipirma pero pumirma na po dahil po sa hindi ko po akalain na ganun, parang ‘yung isip ko po, kinakabahan din po ako,” Japer said, at which point Bosantog continued the questions.

(And then when we signed, I wasn’t supposed to sign but I signed but I didn’t know it would be like that, so my mind was, I was also nervous.)

NUPL’s Julian Oliva denied ever forcing the two, saying that he spent 45 minutes one Saturday explaining the petition in person, and another time on a Sunday where a notary repeated the process of verification with them.

Convincing people to file cases, or persuading them to some extent, is par for the course for human rights lawyers.

Victims who come from poor communities are not quick to sue the government, unlike political detainees. It takes a lot of heart-to-heart talk.

“Ang worry nila ‘yung mga asawa nilang mga minors na kasama nilang nakakulong, ‘yun lang ‘yung narinig kong sinabi nila, nakumbinse sila na kung sakaling ma-declare unconstitutional ‘yung batas, makakatulong ‘yun sa kaso,” said Oliva.

(Their concern is their wives, both minors, who are also in jail. That’s what I heard them say, they were convinced that if ever the law is declared unconstitutional, it would help their case.)

In Bosantog’s version, the NUPL told the Aetas they would rot in jail if they don’t sign the petition. Japer affirmed this.

In Cruz’s version, the NCIP gave false hopes they would be released if they go with them.

In the press conference, Bosantog said: “Hindi naman sa ako ay nagpapangako pero gagawin po namin kung ano ang makakaya namin.” (I’m not promising anything but I will do what we can.)

Calida accused NUPL of paying Japer and Junior P1,000 to split between the two to sign the petition. Cruz denied this, saying that the P1,000 came from their relatives, plus vegetables, to sustain them in jail.

Bosantog asked Japer to clarify.

“‘Yun pong binigay na isang libo po, sir, ‘di po namin alam, sir, na nung inabot po sa ‘min ‘yung isang libo, hindi rin po namin alam kung may epekto para sa ano po sir, para sa….”

(The P1,000 given, sir, we didn’t know, sir, that when it was given to us, the P1,000, we didn’t know if that would have an effect, sir, on…)

He took a long pause.

“Para sa, parang ang pagtingin ko dun, sir, parang, nilalaman din siya ng ano, sir, ng, hindi ko po masabi, sir, dahil hindi ko po gaanong maano, sir,” said Japer with great difficulty.

(That it’s for, in my view, sir, it’s like, it was for, sir, I couldn’t say, sir, because I really couldn’t quite, sir.)

Guerra prodded: What was the P1,000 for?

“‘Yun lang po ang naintindihan ko ma’am, na ang sabi nila ito ‘yung isang libong ibibigay sa inyo pag-budget diyan sa loob,” Japer said.

(That’s all that I understood ma’am, that they said this P1,00 will help you with your budget in prison.)

Not satisfied, Guerra asked more: “Ito po bang pagbigay ng isang libo ay kapalit ng pagpayag niyong pumirma ng dokumento, tama po ba?” (The P1,000 was in exchange for you to agree to sign the document, is that not correct?)

“Nung hindi nila pa pinapirma ‘yung dokumento ma’am, binigay po nila…ibinigay po nila, may sariling pirma po ‘yun ma’am. May iba pang pirma,” said Japer.

(When they weren’t asking us to sign the document yet ma’am, they gave us, they gave, it had its own signature ma’am, there were other signatures.)

They moved on, and got Japer to say that he told his mother to hide from the NUPL when they come.

Getting complainants to desist is not a new tactic for two of the parties involved. Calida got fishermen to withdraw their signatures from a petition suing the government for neglect in the West Philippine Sea. The Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP), which initially represented the fishermen, withdrew their petition soon after.

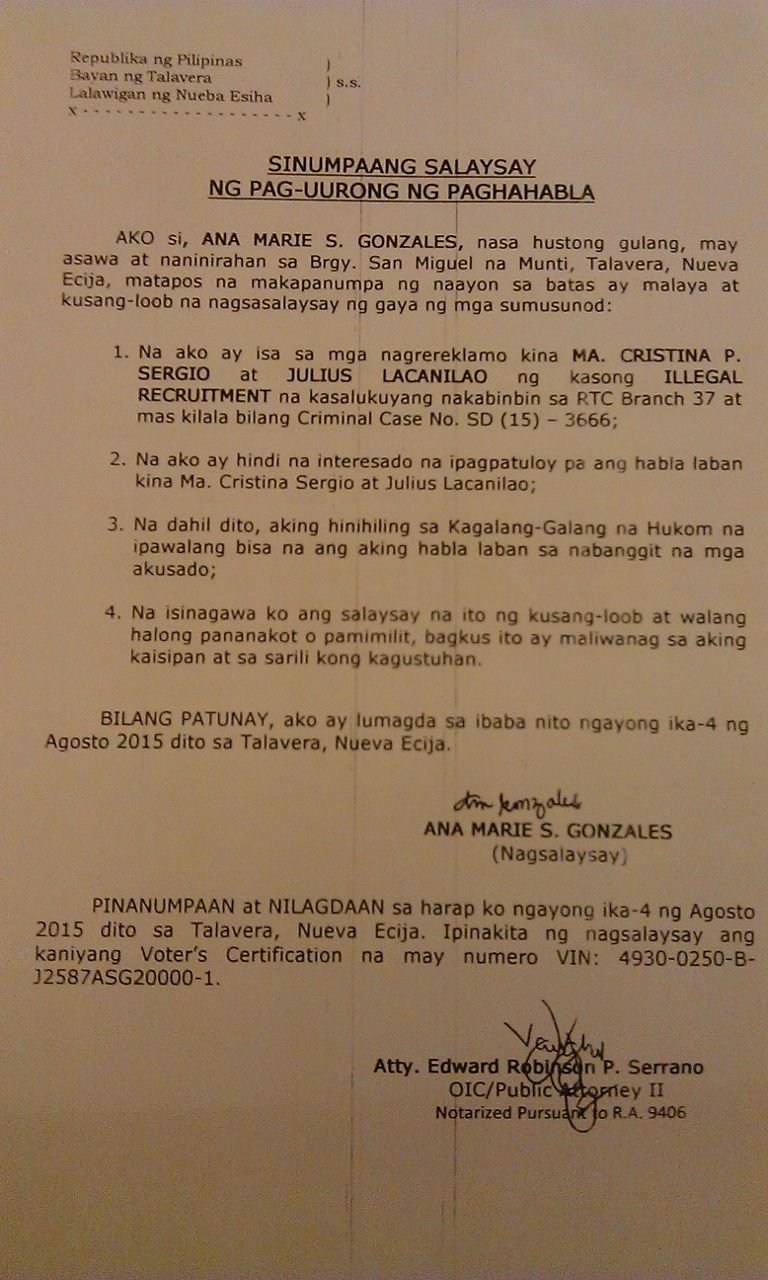

In 2015, PAO got Ana Marie Gonzales to withdraw a suit against Mary Jane Veloso’s recruiters, but the court in Nueva Ecija rejected the withrawal. Gonzales continued with the NUPL. They won the case in January 2020, with recruiters Ma Cristina Sergio and Julius Lacanilao convicted and sentenced to life.

Bosantog said he wants to file a disbarment case against NUPL lawyers. Cruz said they are “contemplating” filing a petition to hold NCIP and PAO in contempt for talking to their clients in their absence.

The issue surrounding the intervention is moot as far as the Supreme Court is concerned, because even before Calida told them of the withdrawal, the justices already had the petition denied due to the pending case in Olongapo. This follows the principle of hierarchy of courts, where cases need to be threshed out in the lower court first before they are considered ripe for intervention by the High Tribunal.

In Olongapo, Japer and Junior formally informed the court on Thursday, February 11, that they have chosen PAO. NUPL will withdraw as counsels on record.

‘Bakit nandito tayo’

For Japer and Junior, it is a tight corner either way. If they go with NUPL, they would be going against a large government machinery defending the anti-terror law. If they go with the NCIP, they would be siding with the same people who believe that the law they are charged under is legal.

Meanwhile they remain behind bars.

Cruz said that if the government wants to help Japer and Junior, they should drop the charges.

“Hindi gagawin ‘yun ng Philippine army na mag-execute ng affidavit of desistance na sasabihin nila na walang kasalanan ‘yung apat na minorya na hinuli nila,” said Cruz.

(The Philippine Army would not execute an affidavit of desistance to say that the 4 minorities they arrested are innocent.)

Guerra told Japer and Junior: “Huwag po kayong mag-alala, magkakampi po tayo dito, kaibigan niyo na po kami, handa po kaming pakinggan ang saloobin ninyo.” (Don’t worry, we are on your side, we are your friends now, we are ready to listen to you.)

“Iniisip namin na bakit tayo napunta sa ganito, hindi naman natin ginawa, bakit nandito tayo, ‘yun lang naman po ang nasa isip namin, hindi namin ginawa, bakit tayo ang napunta rito sa kulungan?” said Japer.

(We’re thinking, how did we get here, we didn’t do it, why are we here, that’s the only thing we’re thinking about, we didn’t do it, but how did we end up in jail?)

Cruz noted that Japer and Junior have not retracted their claims of torture, a claim contained in an affidavit prepared by an NCIP officer.

The NTF-ELCAC press conference did not ask Japer and Junior about what happened on August 21, 2020.

“Dahil po ganun ang pagtrato sa amin, dahil wala kaming pinag-aralan na katutubo, dati ang saya-saya namin sa bundok, pagtatanim, bigla na lang nawasak ‘yung pagsasama namin ng magulang namin, ‘nung wala pong gumulo sa bundok namin ma’am ang saya po ng mga pamilya namin. Nung nawasak na po, parang ang lungkot lungkot na po ma’am,” Japer said.

He cried.

(That’s the way we were treated because we’re illiterate tribesmen, we were so happy before in the mountain, we were farming, then suddenly our family was ruined. Back when they weren’t disrupting our village, our family was happy. But when it was ruined, it got so sad.)

“Huwag po kayong mawawalan ng pag-asa kasi mayroon pong pag-asa, nagsisimula na po ngayon, puwede na pong mabuo ang mga nawasak, lakasan po ang inyong loob at kasama niyo po ang buong gobyerno,” said Badoy.

(Don’t lose hope because there is hope, starting now, you can build back what was broken, strengthen your resolve because the entire government is with you.)

Look who’s talking, said Cruz.

“Sila ang nanghuli, sila ang nag-aresto, sila ang nag-torture, sila ang nagpakulong, at sila ang nag-charge ng anti-terror law,” said Cruz. (It’s them who arrested, who tortured, who had them jailed and who charged them under the anti-terror law.)

In the old Human Security Act, it was also Aetas from Zambales who were charged with terrorism. Edgar Candule, also a farmer, was jailed for two years before he was acquitted in 2010. Under the old law, he was automatically entitled to compensation of P500,000 per day that he was detained.

The new anti-terror law removed the compensation clause.

Japer and Junior do not know what they are looking at, except that today, they know the law under which they had been charged is still legal, and the Supreme Court said they cannot contest it just yet.

All they want is to go back home. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.