SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

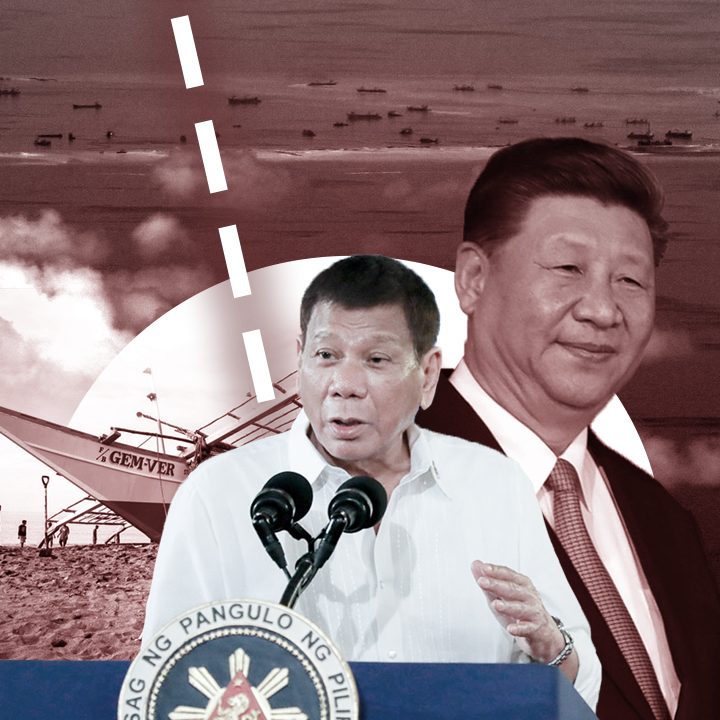

Cut through five years of countless flip-flops, jokes, and contradicting statements, and President Rodrigo Duterte has made it clear where he stands in the Philippines’ battle against China in the West Philippine Sea.

The President’s actions and statements have so far painted an obvious pattern of appeasing China, despite the efforts of some diplomatic and defense officials to assert Filipinos’ rights in their own waters.

Diplomatic and defense sources Rappler spoke to described Duterte’s strategy as one of compromises that had failed to evolve, let alone advance the country’s position in the West Philippine Sea.

Although he was handed the landmark Hague ruling at the beginning of his term, Duterte has failed to use the Philippines’ legal victory to advance the country’s interests. Instead, he has kept with his early decision to downplay the Philippines “ace card” to foster warmer ties with Beijing.

Duterte himself has softened efforts to call out China, using televised addresses to walk back not only his own statements, but those of his Cabinet secretaries.

Even in the few occasions Duterte uttered strong statements on the West Philippine Sea, he made it apparent that he valued preserving good ties with China above much else.

Appeasement fails

Former Philippine ambassador to the United States Jose Cuisia said one needed only to look at Duterte’s reason for courting China in the first place to see that the President’s strategy had been “clearly a dismal failure.”

In the early years of his term, Duterte declared that he preferred the “Chinese way,” saying warming ties with the superpower would pay off in economic gains.

There’s hardly much to show for it, said Cuisia, who also served as central bank governor. “He thought that by being nice to China he would get loans, he would get investments – and he did get pledges, but that is all he got. How much has been realized? What have we gotten?” Cuisia said.

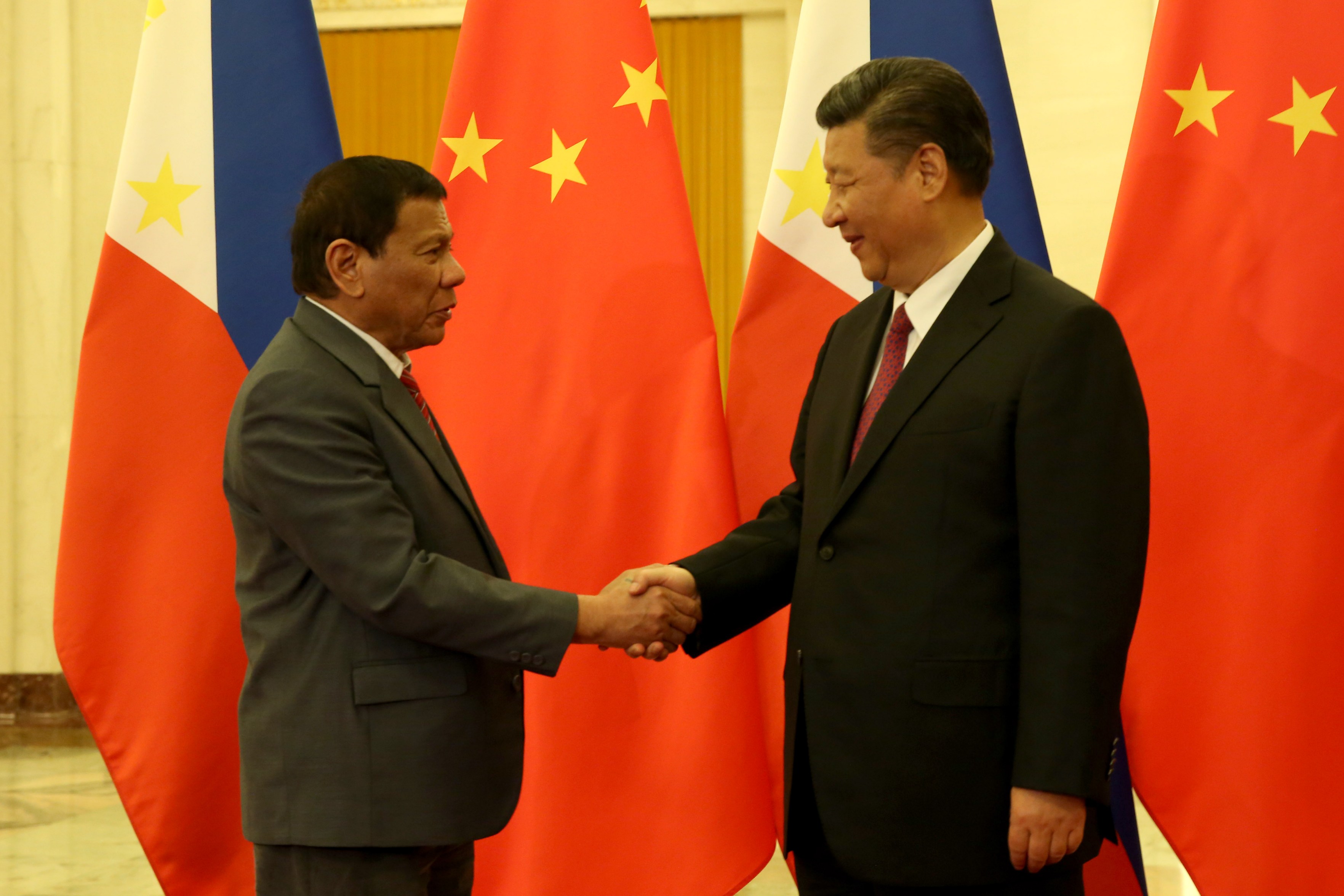

During Duterte’s first state visit to China a few months into his presidency, the government bannered $24 billion (P1.2 trillion) worth in commitments and aid had been signed. China has yet to deliver on most of those pledges.

Political economist and sociologist Alvin Camba pointed out that the trumpeted announcement of signed memorandums of understanding (MOUs) was part of a larger tendency towards “credit claiming,” where the signing of such documents – among the first steps in deals – was publicized “as if [the commitments] were actualized Chinese investments.”

In a June 2021 study published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Camba said: “Duterte’s allies touted the ‘huge’ success of his Beijing visit, making it appear as if Duterte had attained an impressive haul of new economic agreements, financing, and jobs for Filipinos. This trend of credit claiming is quite common to the Duterte administration across the board, particularly in its war on drugs and, most recently, its response to the coronavirus pandemic.”

While some Chinese investments did materialize after Duterte’s visit, they have yet to meet even half of the touted $24 billion announced.

Data from the National Economic and Development Authority as of May 12, 2021, showed one infrastructure flagship program had been completed: the P5.9-billion “China grant bridges” in Binondo-Intramuros in Manila and in Estrella-Pantaleon in Makati City. Thirteen other projects are expected to wrap up in 2022 and beyond: 10 that are ongoing and three that are still in the pipeline.

When it comes to aid, Japan is still the Philippines’ largest donor, accounting for 39% of active official development assistance (ODA), latest government data showed. Japan is followed by the Asian Development Bank, World Bank, and South Korea, while China came in fifth, accounting for 2.7% of ODA to the country.

The Philippines’ MOU with China on oil and gas cooperation in the West Philippine Sea has yet to bear fruit since its signing in 2018, when Chinese President Xi Jinping paid a historic state visit to the Philippines.

Its implementation could have scored a win for Duterte with some of the President’s critics viewing the deal as a possible game changer in unlocking the country’s maritime dispute with China. But the deal is stuck in talks – parties are still working out a way to implement it within the prescribed and agreed upon service contract system of the Philippine government (which implicitly recognizes the country’s rights in the area).

Great concessions

Duterte’s willingness to adjust to China has produced little results. Throughout his presidency, the Philippine leader occasionally took forceful moves on the Philippines’ territorial dispute with China, only to waver over time or falter during moments of candid speech.

Three of Duterte’s arguably most forceful moves have all but petered out. They included his approval to build a fishermen’s “shelter” in Sandy Cay in 2017, explicitly raising the Hague ruling with Xi in 2019, and using his speech at the United Nation’s 75th General Assembly in 2020 to assert the Hague ruling.

To appease China, Duterte gave far too great concessions, defense expert Renato de Castro said. These included Duterte’s decision to delay the full implementation of the country’s Enhanced Development Cooperation Agreement with the United States, setting aside the arbitral ruling, and the President’s decision to limit managing the West Philippine Sea issue through bilateral consultation – China’s preferred means of handling it.

“The bottomline here is, there is simply no point in appeasing an expanding power – for example, China – because whether you are a Chinese friend or not, China would pursue its maritime goal of expansion,” De Castro said in a forum on July 12, the fifth anniversary of the Philippines’ arbitral award.

International relations professor Mely Caballero-Anthony of the S. Rajatnaram School of International Studies in Singapore argued that, while countries like the Philippines would find it necessary to adopt a mix of strategies and hedge with big powers like China and the United States, it was essential to ensure with superpowers that, “number one, there has to be the respect.”

Anthony said the Philippines itself gave basis for this when it took China to court in 2013. “The only weapon you have against the strong is really that you have to use international law, but you also have to be smart. The smart power here is one who is able to navigate,” she said.

She said it had become clear that, while Duterte may be trying to hedge with the US and China, his intentions had been overpowered by dangerous statements from his own mouth.

“If you open up and peel the layers of the onion, it is actually quite clever in the way it tries to hedge, but perception can be overpowering,” she said. “Perceptions matter and statements from political leaders, even if it meant as a joke, matter. And if you don’t have that, you lose the respect of the international community.”

What Filipinos lose

The last five years of inaction and confusion have been costly for Filipinos. While the Duterte government insists it has “not lost an inch” of territory to China, the Philippines has lost credibility after years of appeasing Beijing and downplaying its dispute in the West Philippine Sea.

“The battle in the South China Sea is not just about running after each other. It is also about will, and that will is expressed in the actions you do,” a diplomatic source said.

Former Philippine foreign secretary Albert del Rosario recently lamented how the Philippines lost momentum in asserting the Hague ruling after 2016, saying Duterte’s record of asserting Filipinos’ rights in the West Philippine Sea had been “abysmal.”

Rather than standing up for the Philippines, Duterte took actions that “fit into a disturbing pattern of loyalty to a foreign power,” Del Rosario said.

Cuisia said, while Duterte’s strategy in the West Philippine Sea had failed, the President’s behavior as the country’s chief diplomat had also affected how the Philippines is perceived in the international community.

“For the last five years, what we see is a betrayal of the Filipino people,” Del Rosario said in a recent forum.

“Unfortunately, many times our President acts like a child, especially when he has a tantrum. That is so unfortunate for us,” said Cuisia, who agreed that the Philippines’ international reputation had taken a hit under Duterte.

“You have private conversations with some of the ambassadors, and they will not say it publicly, of course, because they have to maintain goodwill between their countries. But if you get them to rate him (Duterte), he will probably have one of the lowest ratings among Philippines presidents…in terms of relationships between our countries and other countries.” Cuisia said.

By measurable figures, the Philippines has also fallen in competitiveness rankings while investments remain lackluster. The same trend is seen in democracy and press freedom indexes.

But what about recent statements from other Philippine officials that had been more assertive? Since 2020, Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. renewed the Philippines’ commitment to the Hague ruling, calling it a “non-negotiable.” Locsin had also put out another strong statement this year, affirming the country’s commitment to reject attempts to “undermine” or “erase” the landmark award.

The overdue statements were welcomed by the Philippines’ allies, but foreign policy experts had underscored that any forceful words would still need to be backed up by actions. For some of the West Philippine Sea’s staunchest defenders, the Duterte goverment is wanting on this front.

“Have we regained credibility? No. Why? Because we refuse to offend China…. And all the other countries know that,” Cuisia said. “We have lost five years, and that is important.”

Retired Supreme Court justice Antonio Carpio has repeatedly called on the government to conduct freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) with Southeast Asian nations, while Del Rosario has urged Duterte officials to conduct joint patrols with its partners like the US.

However, Duterte’s order to suspend joint patrols in waters beyond the Philippines’ territorial seas remains. Cuisia said it was “ridiculous” that the Philippines did not join FONOPs and other naval exercises when it was one of the beneficiaries of the drills.

Cuisia criticized the Duterte government’s failure to even attempt rallying support for the Hague ruling among countries at the United Nations. The former ambassador said the country could have at least started to lay the groundwork for massing support, pointing out that similar moves done by Nicaragua against the US did not take place overnight.

“Have they even tried?” Cuisia said.

Little effect

On the ground, the limits of Duterte’s strategy are made evident as China has not only stuck to its claim in the South China Sea, but has asserted this even more aggressively.

Data from the Asian Maritime Transparency Initiative of the Center for Strategic International Studies (AMTI-CSIS) show that China’s ships have maintained a constant and increased presence in the South China Sea, including the West Philippine Sea. In 2020, the think tank found this had been sustained despite the pandemic, with the China Coast Guard (CCG) deploying ships around “symbolically important features” on a nearly daily basis, just like it did in previous years.

These features included Panatag (Scarborough) Shoal and Ayungin (Second Thomas) Shoal in the West Philippine Sea, along with features off Malaysia and Vietnam.

In May 2021, AMTI-CSIS said that, while the Philippines had increased its patrols, these “pale in comparison to China’s near-permanent coast guard and militia presence throughout the South China Sea.”

“While Manila’s combination of more public protest and greater presence seems to have had some success in dispersing Chinese vessels at Whitsun Reef and Sabina Shoal, it hasn’t impacted the overall number of Chinese vessels operating in disputed waters,” the group said.

Environmental damage likewise continued in the resource-rich waters, as overfishing and harmful practices cause destruction that can take decades to reverse.

What’s more, hundreds of Filipino fisherfolk continue to witness Chinese harassment out in Philippine waters. Fishermen from Zambales, Pangasinan, and Bataan recently told the government that Chinese vessels restricted their movement in Panatag (Scarborough) shoal and other areas of the Kalayaan Island Group (Spratlys). Others from Mindoro also said it had become more difficult to fish in areas like Recto Bank, where Chinese vessels had crowded the area.

Malacañang downplayed the fishermen’s concerns and denied their experiences, saying they “must not be reporting the truth.”

2022 in view

The situation is likely to stay the same for the rest of Duterte’s term, analysts said. But, clearly, cracks in the President’s strategy have shown.

De Castro noted a slight change in dynamics as he assessed the country was shifting from a strategy of appeasement to one of “limited challenge” against China.

“Some segments in the military and foreign affairs department are starting to question the wisdom and cadence of appeasing a regional power rather than [pursuing] maritime expansion, which puts the Philippines in a very difficult dilemma on how to deal with China’s maritime intention,” De Castro said.

One thing that can also change the playing field is the upcoming 2022 presidential election.

Retired Rear Admiral Rommel Jude Ong said some strong positions taken by Duterte during the period before elections may just be part of efforts to defy the lame duck fate faced by most Philippine presidents.

“In the current set-up of our government and the nature of domestic politics, there is an ambiguous period just before the next national elections when the sitting President is deemed as a lame duck. When this point is reached, the State’s institutions behaviorally take a more independent posture vis-à-vis a current administration’s policies. Perhaps we have reached that point,” he said.

While the government had often been silent on many of Beijing’s incursions in recent years, sources viewed the Duterte government’s recent actions as an attempt to show that they were taking action on the issue. In reality, many of the moves that had been done recently – like increasing coast guard patrols and making protests known – were rarely taken up in the past.

Tough talk can also sound like déjà vu. After all, Duterte has demonstrated the tendency to make statements for show during election season.

Months before the 2016 polls, Duterte said he would take a tough approach with China to apprehend Filipino fishermen who made a living in the West Philippine Sea. “If you can’t stop fucking with us, you’ll see me standing on Spratlys and you’ll just have to kill me,” Duterte said in December 2015.

Cuisia expressed doubt that any substantial change could be made to salvage the losses, citing the Palace’s repeated claim that the country had “done everything” it could on the issue.

“Clearly, it’s just for the optics that they are taking a stand. We are very close to the election and they know the Filipino people are very unhappy with the stance taken by the Duterte administration in the West Philippine Sea,” he said.

With election season on the horizon, Filipinos should recall the pattern of Duterte’s actions and the President’s true thoughts on the country’s dispute with China.

In one of his most recent speeches in May, Duterte denied ever promising Filipinos that he would “retake the West Philippine Sea.” “I did not promise that I would pressure China,” the President said.

Five years later, Duterte proved this right. – with reports from Pia Ranada and research by Paula Marinduque/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[PODCAST] Hear, Hear: Duterte keeps Filipinos under threat in West Philippine Sea](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/05/hear-hear-podcast-sq-may-27-2021.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.