SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

READ: Part 1 | Road to Europe: Paved with exploitation of Filipino truck drivers

In the month of July 2020, Danish authorities announced that they would file criminal charges against Danish haulage firm Kurt Beier Transport A/S and its senior company officials. They are accused of worker exploitation, violation of laws covering the hiring of foreign workers, and violation of various Danish building safety standards for living conditions of workers.

The filing of formal charges is the latest development in a case that dates back to 2018 when a police investigation exposed the maltreatment of Filipino truck drivers and the “slum camps” they were made to live in Denmark while working for Kurt Beier through its Polish subsidiary, HBT Internationale Transporte.

The indictment is based on an exhaustive police investigation that involved the examination of Kurt Beier’s ownership, employment contracts, as well as salary payments. About 30 Filipino and Sri Lankan drivers were questioned in relation to the case.

The Danish Southern Jutland Police provided Rappler with an English translation of its press release which states that Kurt Beier and its key officials would be charged with usury of a particularly aggravated nature. Charges of human trafficking were, however, dropped.

Under Danish law, usury is an act where a person takes advantage of another person’s serious financial or personal troubles, lack of knowledge, or existing state of dependence (such as the case of a contractual relationship). The crime is punishable with imprisonment for up to 6 years.

In addition, Kurt Beier would also be charged with violating the Danish Aliens’ Act for employing foreign workers without the documentation and work permits prescribed by law. The crime is punishable by a fine or imprisonment for up to two years.

Responding to the charges, Kurt Beier CEO Karsten Beier issued a statement on their company website, saying that he was pleased that the human trafficking charges were dropped but found the prosecution’s decision to proceed with the charges of usury “completely and utterly incomprehensible.”

“I look forward to the trial with exalted calm and expect that the court will reach only the correct decision: to reject the prosecution’s claim,” read the statement.

The backroad to Europe

The 2018 exposé of the Filipino truck drivers’ living and working conditions drew much outrage from trade unions and Danish citizens alike, and stirred political action. But how did Filipino drivers find their way to Europe in the first place?

An October 6, 2018 report from Danish social services and the Danish Centre Against Human Trafficking that exposed foreign drivers living in deplorable conditions triggered a police investigation.

The Danish police raided the camp in Padborg, in southern Denmark and found men living in container vans where they slept on foam mattresses on the floor, their belongings crammed into boxes and plastic bags. They shared a total of 4 toilets.

The men said they were close to freezing in the brutally cold Scandinavian winter. (See 3F visual report here.)

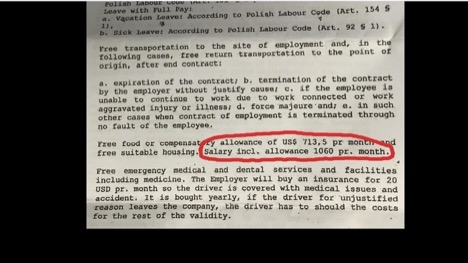

This was the “free suitable housing” promised to them. They were also promised free food or a compensatory allowance of $713.50 per month and a salary of $1,060 per month. A typical Danish truck driver would make up to 32,000 Danish kroner ($5,120 based on 2018 exchange rates) per month.

Kurt Beier employed the drivers through their subsidiary in Poland, where wages are lower, and used this as a loophole to make them work and drive in Denmark and other neighboring countries with higher wage standards while paying them as low as €2 euros (about P120) per hour.

The exposé led to the investigation of reportedly as many as 200 Filipino truck drivers trafficked into Europe. Through the assistance of trade union groups in Denmark and the Netherlands, some of the drivers were given official status as human trafficking victims.

According to Edwin Atema, a lead investigator from The Dutch Federation of Trade Unions (FNV-VNB), haulage companies like employing Filipino truck drivers because of their strong command of English, their amiable easy-going personality, and often, they already have past work experience driving large cargo trucks in countries like the Middle East and Africa.

But the experience of working in these countries did not prepare them for what they would have to endure in Europe.

“Filipino truck drivers told me they’ve worked in Africa and in Saudi Arabia where conditions were also bad but at least they had shower and toilet facilities. It’s worse here in Europe, where they least expected it,” said Atema, who previously worked as a truck driver himself for 10 years.

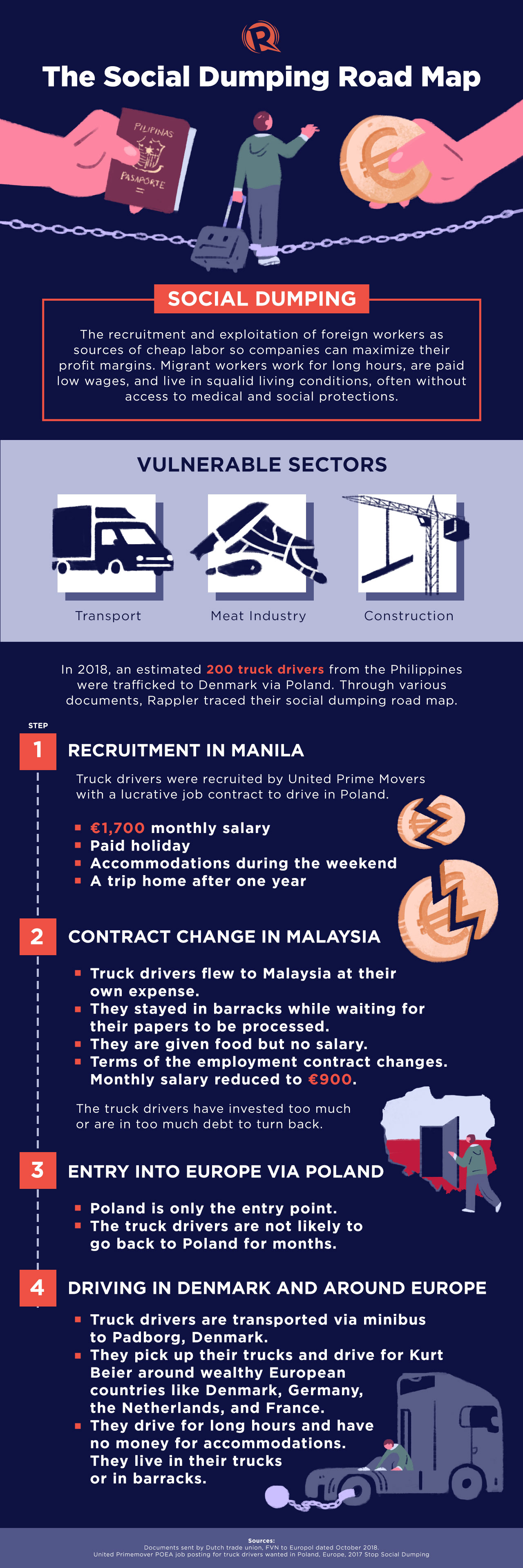

Social dumping

The employment of Filipino truck drivers in Europe is driven by loopholes and varying salary laws across the European Union that allow haulage companies to pay them only a fourth of what a Western European would be paid for the same job. This practice of using foreign workers as sources of cheap labor is called social dumping.

Rappler secured documents based on FNV-VNB interviews with the truck drivers involved in the Kurt Beier case which showed that they were recruited by a local manning agency, United Primover Enterprises Incorporated, which promised a €1,700 (roughly P97,906) monthly salary to work for a Polish trucking company. See the rest of the process in the infographic below.

Some drivers ran away and those who remained were forced to sign a contract that said they would work for the company for at least 3 years or else reimburse the company €2,000 for “training and private outings” that never took place.

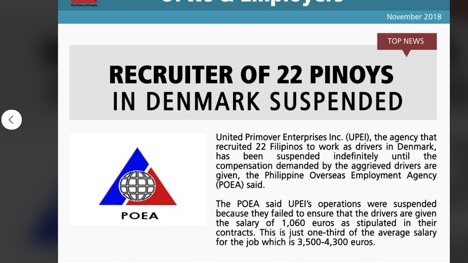

The Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA) suspended the license of United Primover Enterprises in November 2018 until they paid the salaries of the 22 Filipino drivers they recruited. Numerous emails and calls to their Makati office went unanswered.

At present, United Primover Enterprises continues to operate.

A transport sector suffering from a scarcity of truck drivers, companies cutting on costs by subcontracting, and a disparity in standard wages between Western and Eastern European countries have enabled the practice of social dumping.

Third country hiring

Estimates from European trade unions show that there are about 150,000 non-European Union citizens employed as big rig drivers in Europe. They come from low-wage Eastern European countries like Romania and Bulgaria, from other countries farther away like Ukraine – and from as far away as the Philippines.

The various ways that Filipinos enter Europe which include “third country hiring” – or being hired directly by a European trucking company while in another country or by being trafficked by recruitment agencies or intrepid unscrupulous individuals – hinder the government from knowing exactly how many Filipinos work as truck drivers in Europe and what their working conditions are.

Labor rights groups, however, say that whatever route they take, truck drivers are exploited and made to live in appalling conditions. They are made to drive for long periods of time without proper rest or accommodations.

Marlon Toledo Lacsamana, secretary general of Migrante Netherlands-Den Haag, told Rappler via text message about an incident in 2017 where Filipinos were trafficked to Europe by a local Philippine recruitment agency working in partnership with a European company.

The Filipino drivers were flown to Prague in the Czech Republic and from there were subcontracted by French and Dutch employers. They never saw their contract and were paid about €600 ($675 or P33,593) a month, or only about a fourth of what truck drivers would make in the Netherlands.

Many of the drivers did not see their low wages as a form of exploitation. “They think that it is more than they could ever make in the Philippines,” Lacsamana said.

The unscrupulous means of recruiting workers to Europe remain rampant today.

Cheryl Daytec, the labor attaché at the Philippine Overseas Labor Office (POLO) in Geneva, Switzerland, told Rappler that in July, she received complaints from Filipino migrant workers – a mix of truck drivers and other workers – who had paid placement fees of at least P270,000 ($5,400) to work in Europe.

“Migrant workers are not supposed to pay recruitment fees. These are to be shouldered by the employer and should not exceed the equivalent of one month’s salary,” said Daytec.

Shame for Europe

Apart from the Philippines, migrant truck drivers recruited from low-wage countries like Romania are moved in groups via mini-vans to affluent Western European countries and Scandinavian countries like Denmark. From there, they pick up and drive trucks registered in Eastern Europe.

They are given fake documents written in a language they cannot read or understand. These documents say their wages are consistent with Western European laws. They are also instructed by employers to mislead auditors and the police.

Atema emphasized that multinational companies are equally complicit. “There is not one multinational company who can claim that they have no responsibility in these abusive labor practices that trap drivers in slave-like working conditions.”

The European transport industry has, for a long time, been rife with stories of labor rights abuses, illegal practices, and exploitation of non-EU truck drivers.

“The industry,” Atema said, “can no longer deny that exploitation is a big problem and a source of shame for Europe.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] A new advocacy in race to financial literacy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/advocacy-race-financial-literacy-April-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.