SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Jerecah Carian is a 22-year-old mother with four children living in the slums of Malabon City. For the longest time, they made do with a home that didn’t have much: made of plywood and ripped tarpaulins, with a door that blows with the wind. There was food on the table. They had enough cushions to keep their backs off the cold ground.

Jerecah and her family had stood on the edge. All it took was the beginning of a pandemic to push them off it.

She found a lifeline on Facebook.

“Isang pinag palng umaga,” she started in a post to the PROUD MALABONIAN AKO COMMUNITY Facebook group. “Sana po matulongn nio ko khit gatas at makakain lng po ng mnga ank at nnay ko…sana po mtungn nio po ako plz plz po,” she said.

(A blessed morning to all. I hope you can help me, even just for the milk and food of my children and my mother. I hope you can help me, please, please.)

She posted it on May 21, 2020, just two months after the pandemic was declared. It got 18 reactions and 4 comments; she received P800 through GCash.

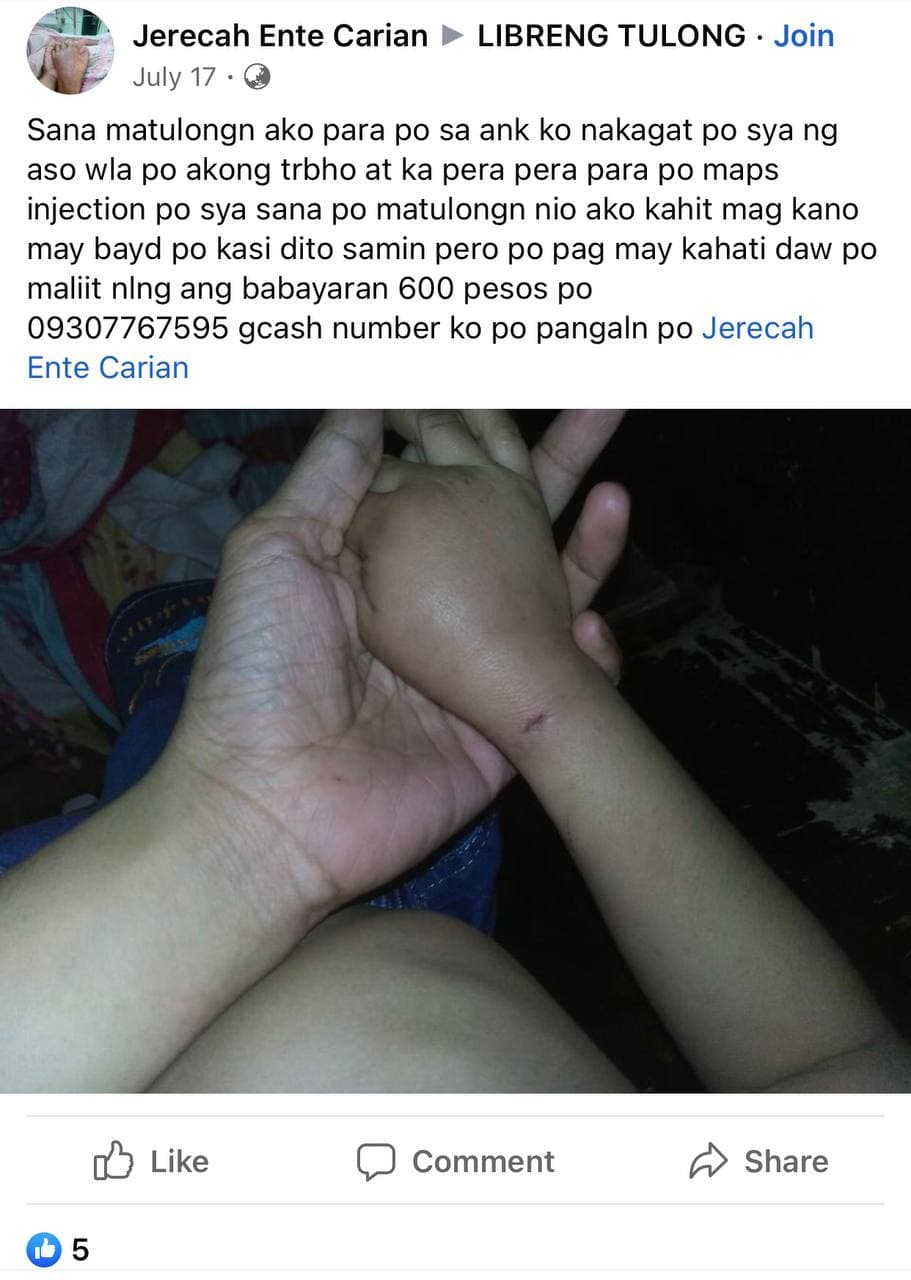

It was the first of at least a dozen times she cried for help in different Facebook groups. Most recently, she asked for help after one of her children got bitten by a dog.

Jerecah’s relatives disapproved of what she did, asking how she had the audacity to publicly ask for help on social media.

Her answer was simple: “Masamang magnakaw kesa maghingi. Minsan nga nagtatalo kami, naiiyak ako. Kung hindi ako hihingi, wala kaming pera,” Jerecah said.

(It’s better to ask for help than to steal. Sometimes, we would argue, I would cry. If I do not ask for help, we won’t have money.)

There are tens of thousands of Filipinos like Jerecah who have turned to Facebook for help amid a pandemic that has blown a hole into the country’s economy and has left millions unemployed and underemployed.

With the pandemic reinvigorated by the rise of variants, and with fresh lockdowns that will further restrict the country, the calls for aid are expected to only multiply.

Rappler scoured some 20 Facebook groups that had been created since the declaration of the pandemic. Their sizes ranged from over 1,000 to over 32,000 members.

Some groups had target members. For example, the Medical Assistance Group – Philippines, with 17,600 members, contained posts more focused on medical-related help, like paying for bills and asking for what to do with ill loved ones.

Another group, the Stranded Negrosanon in Cebu, as the name suggested, focused on helping people who were stranded because of lockdowns.

The story in numbers

Taken together, the groups served as a real-time feed of what poor Filipinos needed during the pandemic.

Rappler compiled and analyzed some 290 posts from the groups between August 10 and 16. This is what we found:

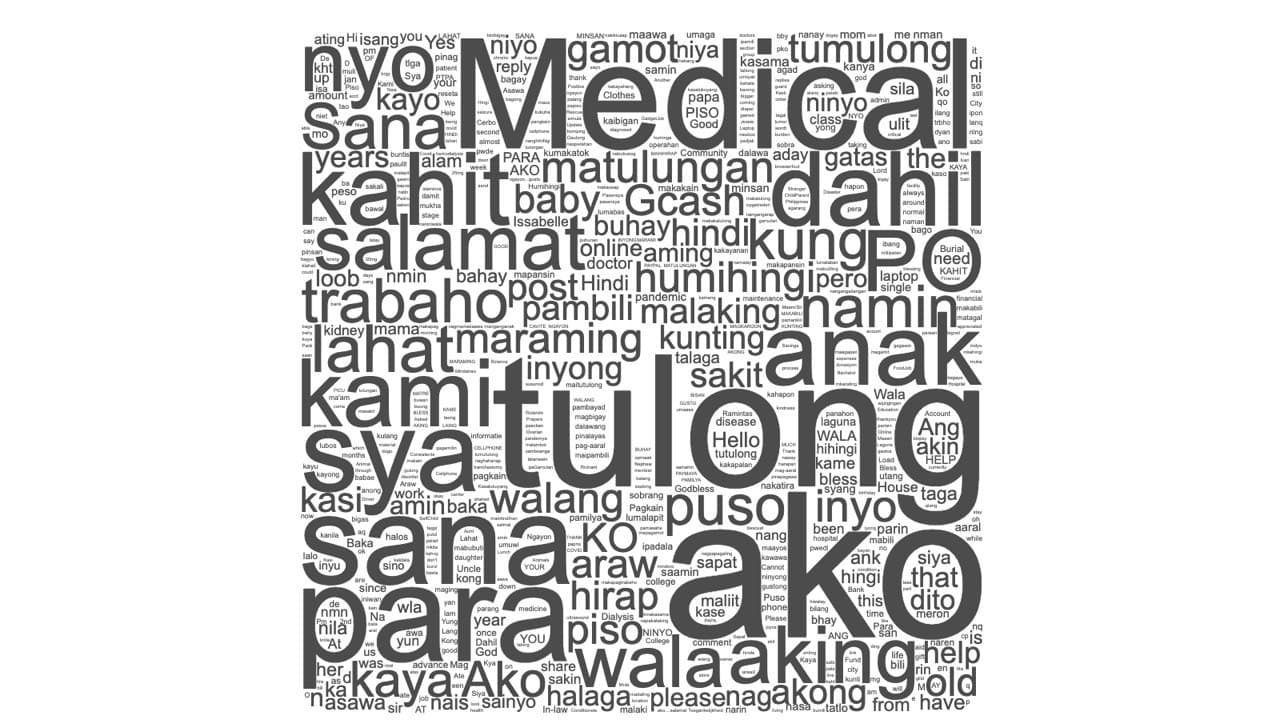

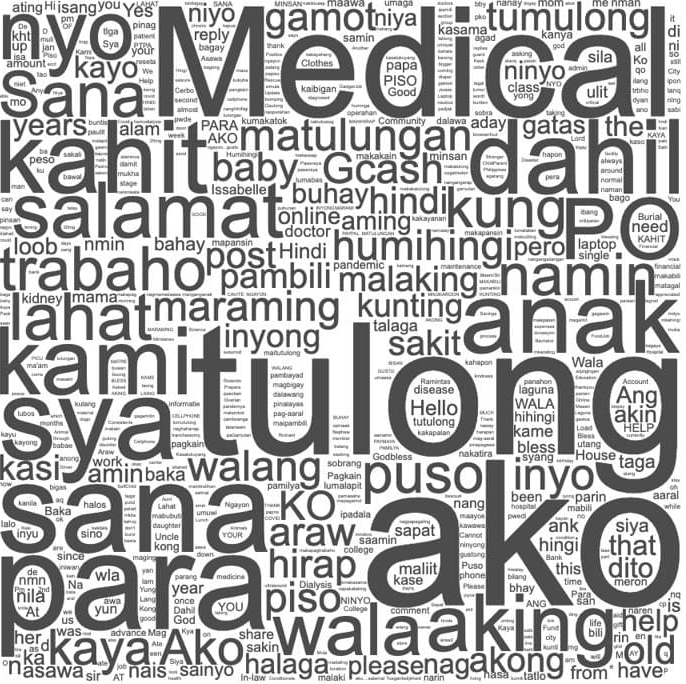

Most of the Facebook posts sought medical assistance for their family members. The most used words in the posts were “tulong (help),” “medical,” and “ako (me or I).”

A lot of them said they already had nothing (“wala”), and they were just asking for money to buy for needs (“pambili”). Sixteen of those monitored even apologized for seeking help, saying “pasensya na po sa abala (Sorry to bother you),” before explaining their dire situation.

The posts were as short as “Baka po pwede makahingi ng tulong pambili po ng gamot ng asawa ko.” (May I ask for help to buy medicine for my husband?)

Some posts detailed what they needed, like one which said:

Sana po ay matulongan nyo po kme kahit magkano lamang po pambili ko lang po ng gamot maawa napo kayo sa akin at sa mga tao po na hinde po nakakaintinde sa ginagawa kong ito na paulit ulit ulit ulit nalang daw pong pag popost ko nito bilang bata eto nalang po kasi ang maitutulong ko sa mama ko para kahit papano sa tulong ng may mga mabubuting puso na nagsesend sa gcash namin ay nakakabili po kme ng ibang mga gamot ko nahindi naman po nahihinge sa center thank you and godbless po sainyong lahat😢😢😢😢😢🙏🙏🙏🙏

Home medicine

Prednisone 25mg once a day

Amlodipine 20mg once a day

Carvedilol 12.5mg 2×aday

Enalapril 20mg 2×aday

Losartan 100mg once a day

Hydrochlorothiazide 25mg 2×aday

Calcium carbonate 500mg 3×aday

Soldium bicarbonate 650mg 3×aday

Ferrous sulfate 325mg 2×aday

(I hope you can help me with any amount so I can buy medicine. Please take pity on me. For the people who do not understand what I am doing, that I post again, and again, and again, it’s because, being a child, this is the only way I can help my mother, so that if good-hearted people will send [money] to our GCash, we can buy my medicines, which are not available at the [health] center. Thank you and God bless all of you.)

The next most frequently posted were requests for food, with a total of 74 posts, 45 of which were by parents asking for help for their children. Of the 290 posts seeking food donations, 89 were for a child or their own children, and 53 were for themselves.

“Kahit piso lang po malaking tulong na po yun (Even one peso is already a big help),” said one woman, who introduced herself as someone from Mindanao and about to give birth soon.

Most of the posts that Rappler found were left unanswered. Of the hundreds, only 67 posts got a reply.

Moreover, a reply did not mean help would come. Some of the replies were just “bumps” or comments meant to push the post anew in the Facebook news feed. Other replies included prayers, and advice on where to get help in their city or barangay.

There were also replies that asked whether the post could be shared in other Facebook groups so that more people could see it.

More calls for help continued to get posted in the Facebook groups while Rappler was already writing this article. Most of them remained unanswered.

A story of desperation

Before turning to cyberspace, Jerecah had approached everyone she knew in person.

Jerecah had a partner – a repacker at a warehouse – who gave her money to support her children. He lost his job in the first 2020 lockdown, and they lost him in his sleep in October, his nose bleeding and his feet turning cold while no one was looking.

Jerecah asked for help from her aunts and uncles. She got hundreds of pesos for the first weeks, but they eventually just “seen-zoned” her – only reading her messages but never replying.

She had an older brother who paid for their rent and utilities, but she could not ask for more, too embarrassed to do so. “Nahihiya na ako sa kanya,” she said. (I’m embarrassed to ask him for more help.)

Jerecah also borrowed money from a nearby sari-sari store, but it eventually stopped lending.

She has a new partner, the father of her youngest, who couldn’t be bothered to help them. “Walang kuwenta,” she said. (He’s worthless.)

Her safety net in shreds, Jerecah took on commission jobs.

“Kung ano’ng puwedeng ibenta, aking ibebenta,” Jerecah said. (Whatever can be sold, I will sell.)

She sold candies and biscuits and tables and chairs. At one point, she sold second-hand washing machines and bottled gummy bears at the same time. She earned a P200 commission for each machine she sold. Each treat-filled bottle had a base price of P25. She added P10 to it for her income.

As months went by, fewer people needed washing machines, and the gummy bears did not taste as sweet anymore.

Jerecah waited for help from the Malabon local government and the national government.

For an entire year, she received a total of P16,000 and a batch of canned goods and rice for her entire family, including her parents who lived with them. None of it lasted for long.

This is why every peso from every Facebook post mattered.

“Kung naipon mo ang piso-piso, magiging 200 ’yan. Malaki na ’yun,” she said. (If you collect one peso at a time, that will add up to 200. That’s already huge.)

She has since returned to selling, now using Facebook to attract buyers through the online acquaintances she made. Her catalog includes keychains, face powders, eyeliners, lipsticks, concealers, wire protectors, boxer shorts, and lumpia.

Jerecah also found another way to make money: slipping people into vaccination sites. She was able to charm her way to the front of the line, along with three customers who each paid her P500 to take them in. They all got vaccinated with Pfizer. She posted an image of her standing against the vaccination site’s photo wall, with the caption, “1dose is done.”

She has paused asking for help, but still opens the help groups to see if they are still active.

“If I’m left with no money again and if someone gets sick – I hope this does not happen – I will return. I’m actually tempted to post because I see other posts getting help,” she said in Filipino.

A story of compassion

Mel Galamiton had to work hard during the pandemic. With both her parents earning P250 per day working at a vegetable farm, Mel had to share the responsibility of keeping their family of five afloat.

The 20-year-old from Canta-ub, Sierra Bullones, Bohol is a single mother to a three-month-old baby.

“Hindi po ako puwedeng umasa sa mga magulang ko, lalo na po at may apat na kapatid pa po ako at may responsibilidad na rin po ako na kailangan buhayin at bigyan ng magandang buhay in the future,” Mel said.

(I cannot rely on my parents, especially because they still have to support my four siblings, and I myself have a responsibility of my own whom I need to raise and give a good life in the future.)

The pandemic exacerbated the already hard-to-access sexual and reproductive health services in the Philippines for young people like Mel. She was also continuing to battle the stigma against young women like her who got pregnant early, while also providing for her family and child.

Mel was a first-year student studying office administration. She stopped her studies because of the pandemic.

She also worked as a saleslady in a mall. Now, she spends her days taking care of her child and tending to her e-loading business.“Barya-barya lang ang kita,” she said. "Kahit papaano po ay may naiambag ako sa mga magulang ko kahit nasa sa bahay lang ako.”

(I earn mere coins, but I am still able to help my parents even though I stay at home.)

Adding to the pressure, Mel’s baby once had to use a nebulizer for a health condition, which made it hard for Mel to work even at home. She counted it a blessing that her child survived the ordeal and that her siblings helped to take care of her.

Still, Mel was driven. She went to “Tulong” Facebook pages and asked for help. She joined the #PisoParaSaLaptop (A peso for a laptop) project on Facebook to help her return to her studies.

With P10 for basic Facebook data, a phone, and a very weak signal, Mel took the chance to share her story. (READ: No student left behind? During pandemic, education ‘only for those who can afford’)

With the shift to distance learning, poor students like Mel had to find ways to cope with the new setup. The pandemic saw families turn to Facebook to ask for help, as they lacked gadgets for online learning and a stable internet connection.

Mel admitted it was hard to ask for help online at first. “Noong una, ayaw [ko] talaga humingi ng tulong dahil nahihiya po. Pero sa nakikita ko na parang nahihirapan na talaga mga magulang ko sa sitwasyon namin ngayon, kaya pinush ko rin ang paghingi ng tulong.”

(At first, I didn’t want to ask for help, I was too embarrassed to do it. But whenever I saw my parents really having a hard time given our situation, I had to push myself to ask for help.)

The viral stories of people receiving aid from random strangers online also gave Mel hope. “Nilakasan ko lang ’yung loob ko na magbakasakali na matulungan ako sa pamamagitan ng pag-post sa Facebook…. Nakita ko na marami nang natulungan dahil sa post nila.”

(I took the chance, hoping that I would be given help through my Facebook post…. I saw that many have received help because of their posts.)

Mel said she has received help from people through the #PisoParaSaLaptop project, although the amount was still not enough to buy a laptop for her online classes.

Despite major setbacks, Mel said that, with people willing to help, she still has hope that she can finish her degree, even with a child. “Naniniwala po ako na hindi hadlang ang pagiging ina para hindi ka makapagtapos sa iyong pag-aaral o maabot ang iyong pangarap sa buhay.”

(I believe that being a mother should never get in the way of finishing your studies or reaching for your dreams.)

Mel had to hold on to this kind of optimism. Receiving no aid from their local government or other private and public groups was not unusual for people in a third-class municipality like theirs. Facebook had been the only platform for them to share their needs and their stories.

A story of hopelessness

Mariel*, 28, is a mother of two. She had used her husband’s account to post multiple pleas to help their youngest child, a daughter with a seizure disorder.

No one had reached out to them so far. They tried to send their baby to the public hospital multiple times, but they were always forced out because of the lack of free beds due to the rush of COVID-19 patients.

“Hindi alam ng asawa ko na nagpo-post ako. Ayaw niya na humingi kami ng tulong dahil inaapakan daw ang pride niya. Pero hindi ko kaya na makita ang anak ko na nahihirapan, gusto kong matulungan ang anak ko,” Mariel said.

(My husband doesn’t know that I post to ask for help. He doesn’t want us to ask for help because that’s a blow to his pride. But I cannot bear to see my child suffering. I want to be able to help my child.)

Mariel is a battered wife. She said their situation has led to fights, and that her husband would hurt her. (READ: During coronavirus lockdown: Abused women, children more vulnerable)

She had to sneak out to talk and share her story. In one of the calls, she had to cut off the conversation because her husband became angry. He didn’t want her reaching out to others.

The mother shared how their child’s medical condition had buried them in debt. She tried to provide for the family by accepting laundry, but whatever money she earned, it was never enough.

Mariel wanted to buy diapers and milk for her children. She wanted to give them a safe home, clothes, and food. But money was always not enough.

Her husband is a taho (silken tofu) vendor, but the pandemic and lockdowns forced him to temporarily stop working. Acquaintances and neighbors had extended them help.

But Mariel had no choice but to take out more debt to support her children. Seeing no place else to turn to, she went to Facebook.

Like Galamiton, Mariel saw users being given aid in viral posts, and sought out pages where people were allowed to post their condition.

Using P10 pesos for basic Facebook data and an old phone, Mariel also took the chance, hoping people would see her child’s condition and help them with the medical expenses.

Mariel's last text was an update: “Hindi pa rin po kami tinatanggap sa hospital.” (We are still not accepted in the hospital.)

A story of communities

Stories of desperation were what drove Sammy Gerogalin, a moderator of “Libreng Tulong” Facebook page, to create a space where people could freely post their pleas for help.

Sammy said that he had seen other “Libreng Tulong” pages before, and wanted to create another one himself. Any post was permitted, so long as it was not spam and did not use derogatory or disturbing subjects.

“Karamihan, laging mga nanay ang humihingi ng tulong,” Sammy said. “Tulong pinansiyal lagi ang karamihan sa mga posts, pampaospital, pambili ng gamot. Tulong para sa pamilya ang laman ng mga posts.”

(It’s always the mothers who ask for help. They ask for financial assistance, to pay for hospital bills, to buy medicine. Wanting to help their families, that’s the subject of most of the posts.)

Mothers, mostly from Metro Manila, make up the bulk of posts on Sammy's page. (READ: Pandemic scars: More Filipinos to remain poor, unemployed even by 2022)

He said it hurt to see people helpless and pleading online.

Sammy admitted he would not know if the people posting on his page got the help they needed, but said he needed to try to ease their burden.

He was also aware that more powerful entities like the government should be helping fellow Filipinos.

“Pero hihintayin mo na lang ba kung puwede ka namang makatulong, kung makakaenganyo kang tumulong kahit papaano?” (But why wait if you yourself can extend help or encourage others to help?) – with research by Jean Raoet/ Rappler.com

*Name was changed to protect the identity of the interviewee

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.