SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

There are many faces in the coronavirus pandemic. For some, it’s a family member ill with the virus, a doctor caring for the sick, or the nameless policeman monitoring people’s temperatures at checkpoints.

Among these many faces are women frontliners, whose task to care for the most vulnerable stretch from their homes into the workplaces they serve.

Together, they fill the ranks of those who form the front lines guarding communities against a pandemic.

Health before politics

Dianne de Castro has been a nurse at the Philippine General Hospital for 4 years, the same time that President Rodrigo Duterte has been in power.

The hospital, the largest government-owned health facility in the country, became a COVID-19 referral center in April, though Dianne has been a COVID nurse since March 16, the day Duterte put Luzon on lockdown.

At that time, she felt like they were “being tossed to the sharks” without proper government support.

It’s been 4 months since Dianne has been working 8 to 10-hour shifts in one of the busiest hospitals in the country.

“I don’t feel secure working in this pandemic,” she said, adding their hospital mostly relies on donations for personal protective equipment, and that the staff have even once had to reuse their N95 masks to be able to work.

“That scares me because I am putting myself at risk doing this daunting job that I used to love,” she said.

Dianne’s fears are not misplaced. Frontline healthcare workers are among the most vulnerable to COVID-19 with 4,094 confirmed to have COVID-19 as of July 21.

Dianne said that many of her colleagues have resigned.

“I hope the government can re-evaluate the things they are doing and really check in if we are getting the results we should and not be complacent with what we are getting,” she said.

She appealed to the government to put the people first: “I beg you. Put the country first. In a pandemic and a time of crisis, put people before politics. Put lives before money.”

The protector in Bayombong

Police Corporal Florence Gumilab does not touch her firstborn son Hawthorne each time she arrives home after a long day at work.

She must first bathe outside their house, disinfect her uniform and belongings, then leave them out to dry. When she gets inside, Gumilab waits for another 30 minutes before she finally showers her only child with hugs and kisses.

Gumilab does this every day because her job as a checkpoint frontliner in Bayombong town, the capital of Nueva Vizcaya, makes her vulnerable to COVID-19.

“I fear he might get infected. But I always pray it doesn’t happen to him,” said the 32-year-old mother.

The pandemic was still in its early stages in March when Gumilab was ordered to pack her bags, leave her home in Manila, and move all the way to Bayombong. The order was tough because Gumilab had to be away from husband Leonardo, who is a cop assigned to the Firearms and Explosives Office at Camp Crame in Quezon City.

Gumilab is still breastfeeding Hawthorne, who will be turning two in August. She is thankful her mother agreed to move with her, so someone could look after her son during her 12-hour shifts.

These days, Gumilab divides her time between her duties as a policewoman and taking care of her baby. Her unit allows her to go home to breastfeed Hawthorne, even during her duty hours.

But she admitted she finds it challenging to be a lactating mother and a checkpoint frontliner during this COVID-19 crisis. If she isn’t careful, she could bring the disease back home. As of July 21, the Philippine National Police tallied 1,600 confirmed cases among its personnel, 9 of whom already died of COVID-19.

“I really have to divide my time as a frontliner and a mother. That’s the hardest experience for me during the pandemic, because I can’t just neglect my baby when I’m working,” she said.

So every day, Gumilab scrubs herself outside her home, douses her uniform with disinfectant, and waits 30 minutes to hug and kiss her son.

Some days are more tiresome than others, but Gumilab draws strength in prayer.

“I am able to do this because of my strong faith in God. Whenever I feel tired, I just call His name and I find my strength again,” she said.

Facing a double pandemic

At 43, Orlyza Rosales has spent the last 7 years teaching at a Quezon City public school and is proud she has learned to navigate challenges that come with being a teacher in the Philippines.

But lately, Rosales admitted it has been more difficult to find her footing. Deep into preparations for the coming school year, Rosales is one of the nation’s 880,000 public school teachers who have had to relearn how to teach after the pandemic shuttered schools.

She is sure to avail of every opportunity to prepare for the Department of Education’s (DepEd) “blended learning” approach that involves a mix of distance and online learning. From attending online seminars, paying for training workshops, and traveling to her school to keep up with work – Rosales did it all.

But the pressure to get back to schooling while cases are still rising has left Rosales feeling under siege. Every time she leaves home for work in school, she fears bringing home the virus to her husband and children.

“We’re risking our lives, to be honest,” Rosales said.

Coronavirus cases have been increasing in Quezon City, yet she and her peers do not have access to any form of testing. This concern comes on top of waiting for resources for the school year promised by the government.

Still, Rosales knows she cannot step back from her job. Despite the risks, teaching, she said, has become more essential.

“I worry I’ll be the reason why my family gets sick but I can’t do anything but keep working because for now, my husband is in a no work, no pay situation….It’s really tough. I’m just hoping I’ll be able to keep up,” she said.

Rosales said teachers struggling to meet the logistical and financial challenges of reopening the school year should be given adequate support by DepEd. This starts with answering crucial questions about aid for students and how teachers will be supported so they can continue instructing students.

“If DepEd is serious with deciding they want to push through with classes this August, they should provide what students and teachers need. If they can’t do that, we’re just kidding ourselves,” she said.

When Rosales is overwhelmed, she remembers how she wanted to become a teacher when she was younger. “This is our vocation. So even if it’s difficult, because it is our work, we love it and we love our students. Whatever challenges we face, we want to help our students because they’re having a hard time now too. If we give up, what happens to them?” she said.

Children left behind

“The only concern is DSWD seems to have forgotten about the orphanages and residential homes. We, in this time of pandemic, also need help,” said social worker Kristine Edris Abel.

Abel works for Meritxell Children’s World Foundation, a non-governmental residential agency that’s registered and licensed to operate as an orphanage.

Abel admires her colleagues who are medical social workers in government hospitals and who distribute aid for DSWD. She considers them brave and an inspiration.

“Social workers are frontliners too. They also put themselves in the way of danger for the public,” she said, after mentioning that some of her colleagues have been criticized by the same people they serve.

Still, her concern is the 19 children she is responsible for at Meritxell – how they’ll survive now that they’ve stopped receiving donations, and how they will learn, as they aren’t sure how DepEd’s blended learning approach will work for students at different grade levels.

Even before the pandemic, Abel said it was hard enough for children in orphanages as they lacked support from the government and already had difficulty finding families. Finding a permanent home for a child could take years of waiting and paperwork and the process takes even longer now in a pandemic.

“The children get frustrated, and I feel the frustration thrice,” Abel said. “They trust us with their lives. Their families left them, they left their families because they were hurt,” she said.

“I hope we don’t also abandon and hurt them with the length of time it takes for them to have a family they can call their own.”

‘Mama will find a way’

Nilda Lobaton, a mother of 4, talks about the upcoming school year with uncertainty in her voice.

Two of her children – Jeremy in Grade 9 and Jericho in Grade 6 – are part of the incoming batch of students who will be forced to attend classes online while the country still grapples with the coronavirus pandemic.

Yet roughly a month before school starts in August, Lobaton and her husband Bernie have not yet enrolled their sons in school.

“I’m still thinking about it. In distance learning, they will have to use gadgets. But we don’t have a laptop! Ours is already broken,” Lobaton said.

The 48-year-old mother added they do not have internet access at home.

Lobaton is a health worker with the provincial government, while her husband is a security dog handler based in Quezon City. They earn enough for the family’s daily needs, but the couple does not have any extra cash to buy laptops for sons Jeremy and Jericho.

The Lobatons are not alone. More than 6 million students failed to enlist for the coming school year, even with DepEd already extending the enrollment period.

Parents, teachers, and even students nationwide have criticized DepEd’s decision to open classes during a pandemic as household finances have been severely affected by the lockdown.

If it were up to Lobaton, she would rather that government postpone classes completely, so no student would be left behind.

“In my heart, I am hoping that there will be no classes anymore. Let’s try to postpone classes even for just a semester,” she said. “Then maybe they can figure out a way to make sure holding classes would not be such a burden to students.”

Lobaton said Jericho is afraid to go back to school, but she tries to ease the worries of her youngest child.

Leave it up to Mama, she told him.

“He is scared. But I told him, ‘Son, you will go to school. We will find a way.’”

Act now, act fast

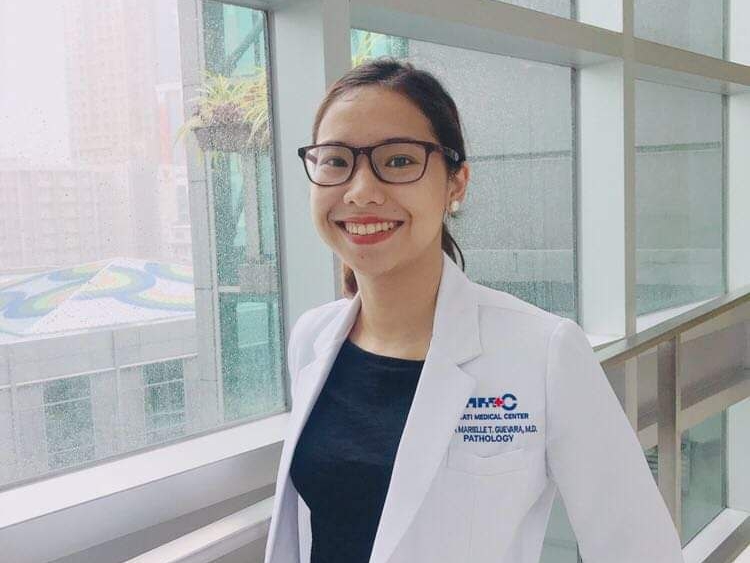

Marielle Guevara-Belmonte, a pathology resident, is among the thousands of health workers who have been working to treat a disease that has no known cure or vaccine.

She told Rappler that she’s disappointed with the government’s handling of the pandemic. “There are so many things they could have done differently which could have hastened the flattening of the curve and yet here we are, still with cases on the rise,” she said.

As of July 21, 4,094 healthcare workers have tested positive for COVID-19. Of these, around 3,275 have recovered, 35 have died, and one is in critical condition.

Part of the frustration Guevara-Belmonte feels with the government stems from the opposite response she saw as an intern at a government hospital. At that time, she said medical supplies were readily available and more hospital beds were being procured for expansion..

Today, she and her colleagues are left to make the most out of what they’re given, rely on each other for emotional support, and find consolation in every swab test that comes back negative.

“We’ve been continuously stretching out the limits of the healthcare industry,” Guevara-Belmonte said.

“We cannot exhaust all efforts done by healthcare workers. We need a government that is systematic and data-driven to lead the fight against this pandemic. We need to act now and we need to act fast.” – Rappler.com

Editors note: Quotes have been translated to English

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.