SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The dictator Ferdinand Marcos loved to portray himself as a strong and powerful man as he ruled the Philippines for more than two decades.

But under all the pretense was an ailing man desperately clinging on to power.

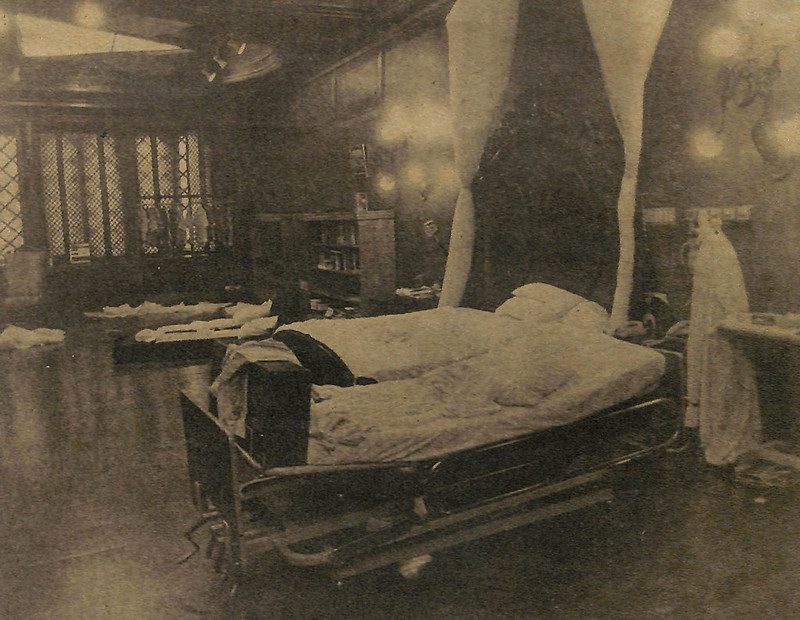

“A refuge of a very sick man” was how Associated Press (AP) reporter Ben Alabastro described a room they found inside Malacañang Palace after the 1986 People Power Revolution.

The public flocked to the Palace that the Marcos family and their closest cronies hurriedly escaped from a few hours earlier.

Alabastro wrote that the room had a hospital bed and a box of syringes, while the air allegedly smelled of medicine – telltale signs of what the Marcos government concealed for many years.

Kidney problems

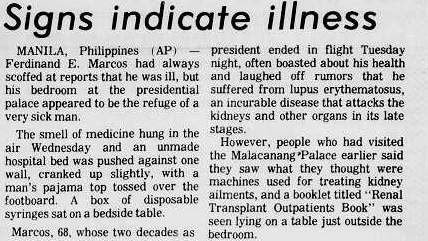

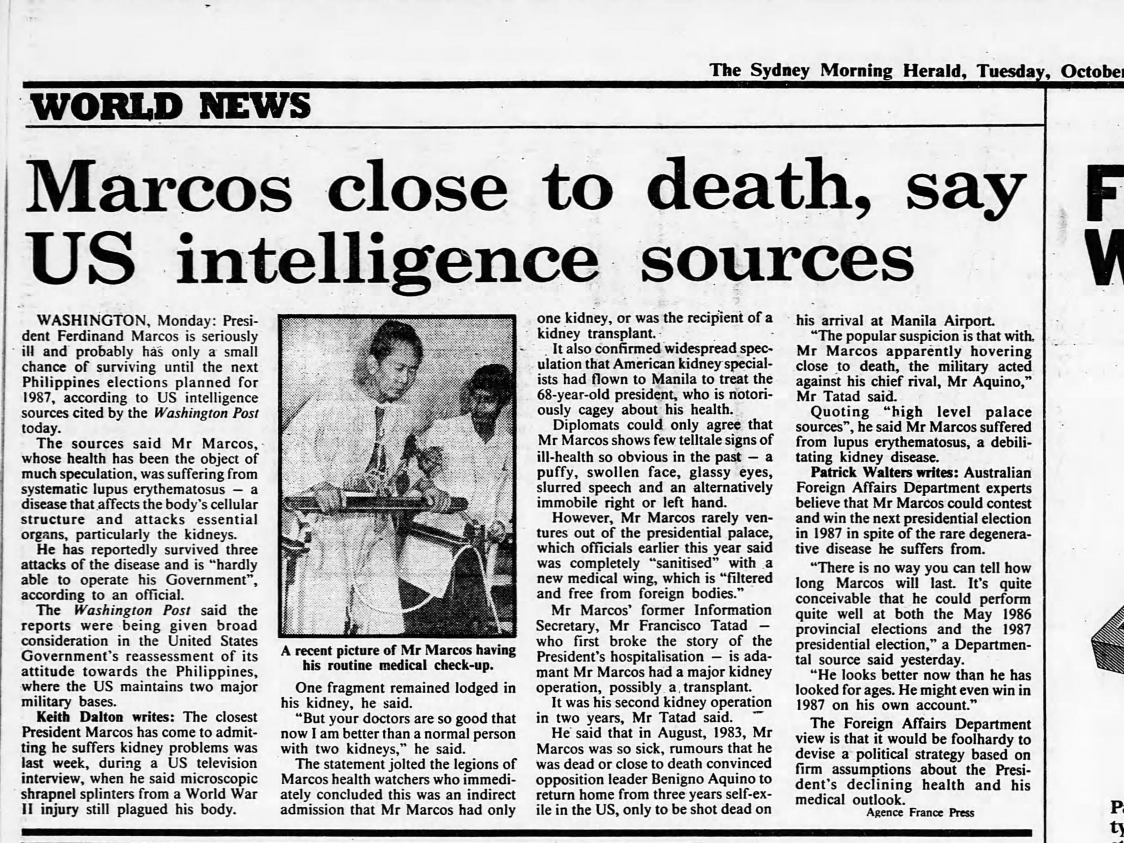

Before the peaceful revolution, there was no shortage of rumors surrounding the dictator’s reportedly failing health – that he was suffering from lupus, among other ailments.

But due to tight government control, it was hard for people to demand for transparency, specifically the release of medical bulletins.

David Briscoe, Associated Press (AP) Manila bureau chief during the latter years of the regime, remembered that it was in 1982 when information about Marcos’ kidney problems started going around.

AP covered major presidential conferences, among others. It meant monitoring what was happening to Marcos was a major task. Stories produced by his reporters were published in several newspapers abroad.

In 1984, Briscoe said they noticed Marcos “dropped out of view for several weeks,” and that there were sourced reports that “his body had rejected the first kidney, making another transplant necessary.”

“But Marcos and the palace continued to deny all negative reports on his health,” he told Rappler in an email.

Miguel Suarez, then AP news editor, said that opposition figure Benigno Aquino Jr told him that in 1979, Marcos was suffering from Lupus Erythematosus, an autoimmunine disease.

He can’t remember if he used the information for a story since it was off the record, and there was no way to confirm it from officials.

“Lupus makes one sensitive to sunlight and causes rashes on the skin, especially the face,” Suarez told Rappler. “So, at least to me, that explained why Marcos was always made up and he was seldom outdoors and someone held an umbrella.”

It was in December 1984 when a government official finally went on record about Marcos’ health. Then labor minister Blas Ople told the New York Times that “the health of our leader is undergoing certain vicissitudes, problems.”

Marcos, he assured the public, was “in control but cannot take major initiatives.”

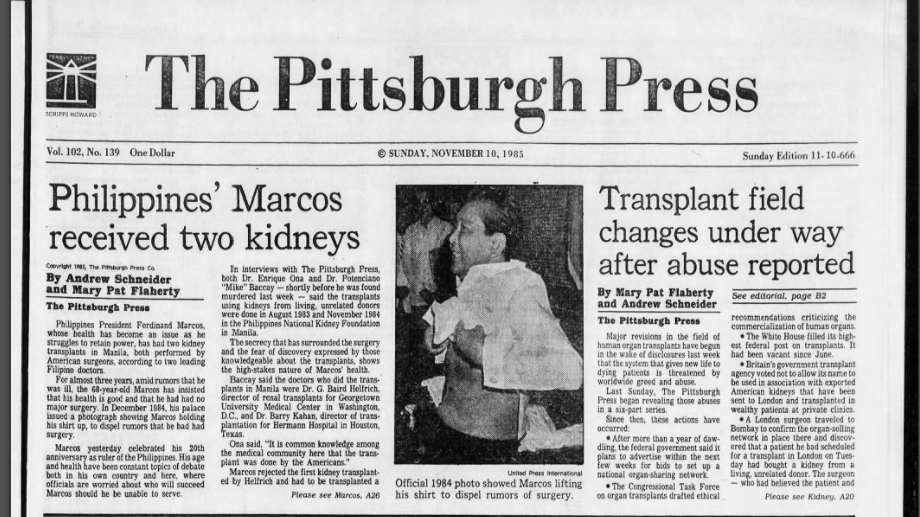

A story published by The Pittsburgh Press in November 1985 affirmed reports about Marcos’ kidney issues. It also gave a clear picture of what Ople meant by “problems.”

According to the report, Marcos underwent kidney transplants in August 1983 and November 1984 at the National Kidney Foundation (now the National Kidney and Transplant Institute).

It named Dr Potenciano Baccay, the vice president of the hospital, as one of the former president’s physicians. Malacañang called the report “sheer fantasy.”

In November, it was reported that Baccay was stabbed to death after being abducted from his home in Muntinlupa City.

Read the full 1985 report:

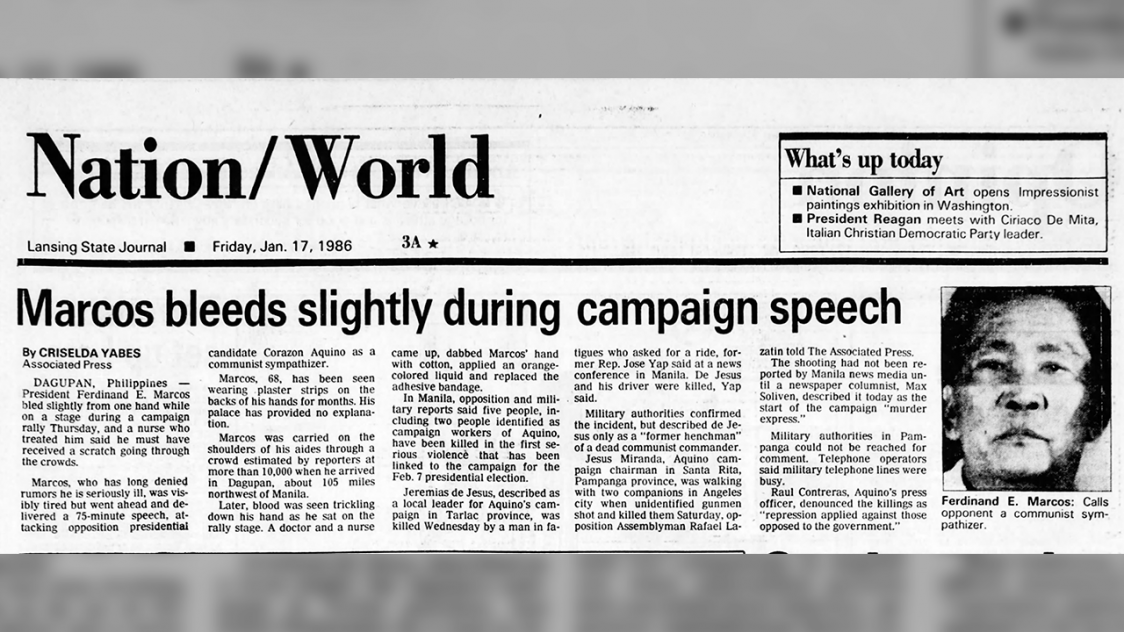

Marcos bleeds

Catholic priest Rolly de Leon was a human rights worker in Bulacan during the latter years of the dictatorship. He closely followed the news about Marcos as he conducted his work in his province.

Rumors about Marcos’ health were floating around. He recalled one incident when blood was seen on the cuff of the president.

“Naisip ko na there really must be something wrong,” he told Rappler in a phone interview. “Kung hindi man sa health niya, baka sa katawan, kasi bakit nga may tatagas bigla na dugo, di ba?”

(I thought there really must be something wrong. If not his health, but his body, because why would there be blood trickling?)

This was during the campaign period for the snap elections in 1986. Reporters saw a bandage come off Marcos’ hand, and then they saw “blood trickling down.”

“The next day, his hand swathed in bandages, Marcos claimed an ardent supporter had scratched him trying to shake his hand,” Briscoe said.

Journalist Criselda Yabes, in her report from the campaign rally, described Marcos as “visibly tired” and was carried on the shoulders of his security men.

“Marcos, 68, has been seen wearing plaster strips on the back of his hands for months,” she wrote. “His palace has provided no explanation.”

Image of a ‘Filipino superman’

Nilda Sevilla was a professor of political science and sociology at the National College of Business and Arts during Martial Law. As a teacher during turbulent times, she tried her best to impart to students only the truth, even if the government was trying to suppress it.

“Palagi kong sinasabi na importante sa governance na transparency,” Sevilla said. “We have to search for the truth, kung ano ba talaga ang totoong nangyayari.”

(I always said that transparency is important in governance. We have to search for the truth, what’s really happening.)

Transparency was absent during the Marcos administration, most especially in relation to the health of the dictator. She remembered how different the face of Marcos became in the early 1980s and how the Palace stopped releasing photos of him with the crowd.

There was even reportedly one video which featured Marcos delivering a speech supposedly from Malacañang. People on the ground knew better.

“Alam mo ang mga Filipino, mapaglaro ang isip talaga, kasi ang sabi-sabi na noon ay bakit walang presidential seal sa background? Bakit puti na dingding, like a hospital?” she said. (Filipinos have playful minds, they said why is the presidential seal missing? Why is the wall so white like a hospital?)

But Malacañang continued to deny that Marcos was sick amid all the rumors and reports. The government went on to carry out events to “prove” the dictator was well.

“I don’t recall the circumstances, but at one point Marcos raised his shirt to reveal a scarless abdomen, evidence, he said, he had not undergone any kidney transplant, as if that would be the place for the surgical incision,” Suarez said.

He also recalled seeing a photo sent out to the media by the Palace press office “to dispel rumors that Marcos was bedridden and unable to walk on his own.”

It was reportedly a photo of the former president dressed in a robe and seated on a large armchair, but the bottom part was blacked out.

“Curious, I tried rubbing off the ink with a wet rag so luckily, the ink came off easily to how the armchair was mounted on a platform fitted with wheels,” Suarez said. “Proof, Marcos couldn’t walk and had to be wheeled around.”

Such was the image of Marcos who ruled with an iron fist in the Philippines. His robust health was part of his branding – an infallible and unyielding president.

Marcos was portrayed as the Malakas to Imelda’s Maganda, the key figures lording it over the country.

“Nabasa ko sabi pa raw niya he does not intend to die, biruin mo naman sabihin niya iyan, akala mo ba hawak niya buhay niya pero hindi naman,” De Leon said. (I heard he even said he does not intend to die. Imagine him being able to say that, as if he has control over such thing, but not really.)

But as Marcos’ illness reportedly worsened, his public appearances became less frequent.

He did not mingle with huge crowds anymore, nor had constant meetings with dignitaries. He was away from the public eye far too often.

Suarez said Marcos would appear on the evening news reportedly wearing the same barong. Press briefings, previously conducted weekly, only happened “whenever he looked good.”

“Under this setup, it was easy to keep the lid on Marcos’ health,” Suarez said. “Excerpt perhaps for a few officials, but even most of them would have been kept in the dark.”

While he cannot recall outright stunts, Briscoe said “the palace was always pushing an image of Marcos as a kind of Filipino superman.”

Openly questioning the denials of Malacañang in the face of obvious physical signs was risky. The regime was hell-bent on suppressing opposition and the media, after all.

“Who would be brave enough to talk, especially after rumors that the doctor who performed the implant had been killed?” Suarez said.

Political, economic chaos

The latter half of the Marcos regime saw the Philippine economy in shambles and the pockets of cronies full. (READ: Marcos years marked ‘golden age’ of PH economy? Look at the data)

People were understandably agitated by the situation the country was in.

“It’s not that [the people] were worried about Marcos, but more on na very economically unstable na nga, magkakaroon pa ng political instability,” Sevilla, now the co-chairperson of Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance, said.

(It’s not that [the people] were worried about Marcos, but it was more about political instability adding to the economic instability.)

Activist Manjette Lopez, meanwhile, was helping build a stronger and broader alliance against the dictatorship when reports about Marcos’ failing health became rampant.

They knew that the system in place since 1972 was already strong – fueled by cronies and loyal military men – but the death of Marcos meant something else.

“Mas naiisip namin, definitely manghihina na [ang structure] kapag nawala siya kasi siya ang main adversary ng democracy… because he knew the law, he knew the requirements of authoritarian rule, at kung paano siya mananaliti,” Lopez told Rappler in a phone interview.

(We were really thinking that the structure he put in place would lose its power since he’s the main adversary of democracy because he knew the law, he knew the requirements of authoritarian rule, and how he would remain in place.)

Marcos’ inner circle still made sure to maintain the status quo. Killings and other human rights abuses did not stop. In 1983, his fiercest critic Benigno Aquino Jr was assassinated.

Lopez recalled that even during the last few years of Marcos rule, at the height of rumors about his health, she and her colleagues were still witness to slaughter and violence.

She would often go to different parts of the country to document these human rights violations – proof that there was no stopping the Marcos policy of abuse.

“When a beast is in the throes of death, mas mabangis siya (he lashes out harder),” Lopez added. “When a tyrant is under siege and under assault na, mas mabangis iyan (he becomes more savage) before they die, but they die.”

They wanted to know what the real deal was. A 1984 report by the United Press International said that his “obvious poor health” sparked a mad scramble among opposition politicians regarding his would-be successor.

Lopez recalled noticing this from the politicians who were part of the movement, too. But for her and other activists, the most important thing was to install a “much more thoroughly democratic” government after the two-decade Marcos dictatorship.

“It should become a true government of the people,” said Lopez, who is now president of Sanlakas and vice president of Laban ng Masa.

De Leon, meanwhile, believed Marcos had a plan in place. The Catholic priest, who is now the co-chairperson of the Promotion of Church People’s Response, remembered thinking it was Imelda Marcos who would take over.

Imelda, after all, enjoyed immense power during the Marcos regime.

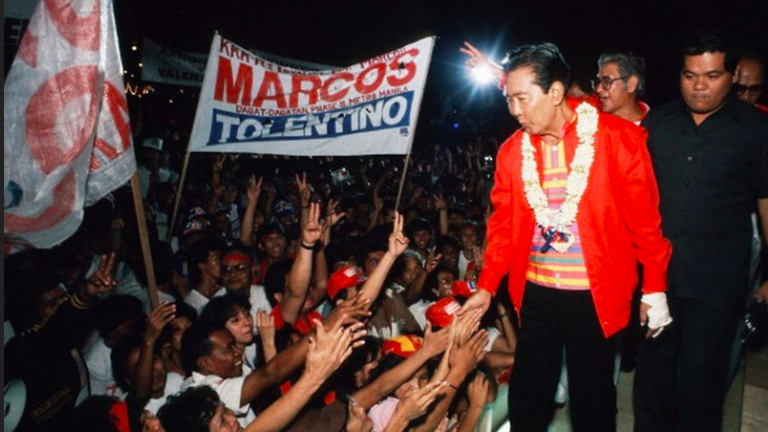

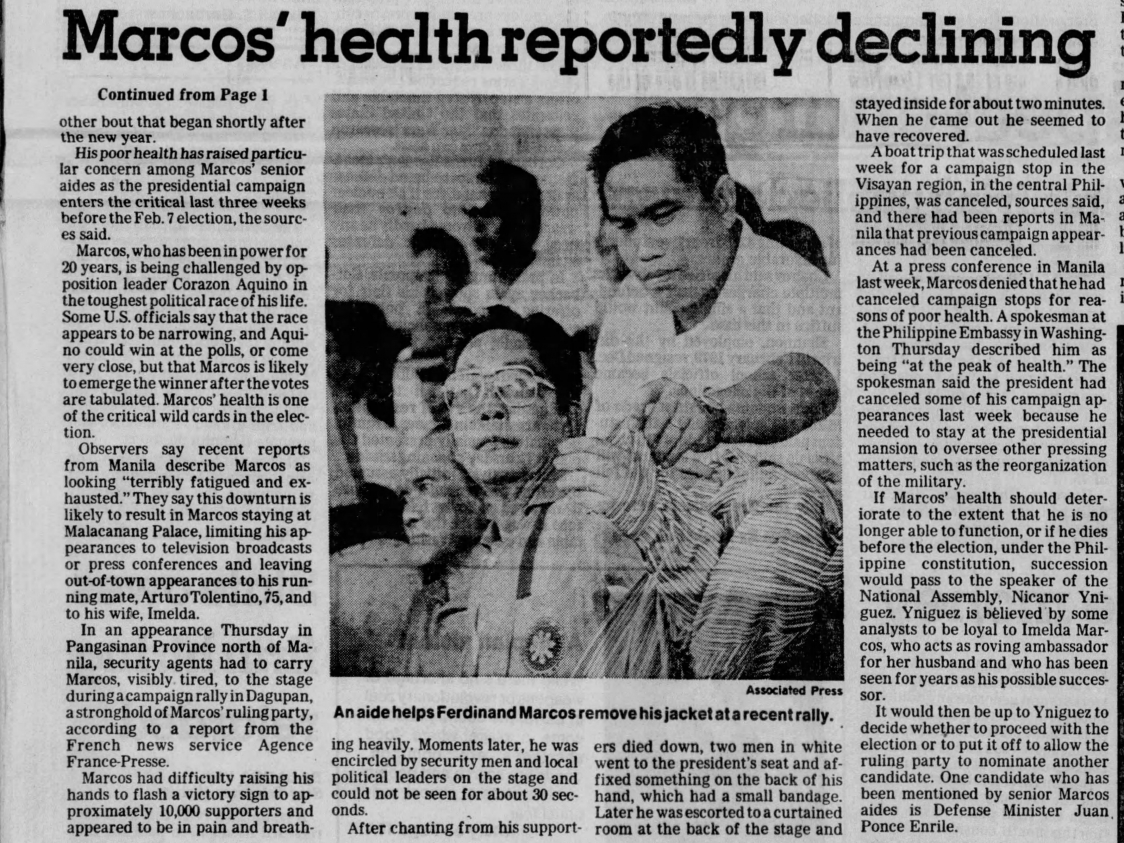

Marcos’ last few months in power were spent campaigning for the 1986 snap election against Corazon Aquino, the widow of Ninoy.

His camp canceled campaign sorties allegedly due to other engagements. They claimed there were meetings Marcos needed to attend, or important decisions he had to mull over inside the comforts of Malacañang, away from the crowds.

Reports described Marcos as “terribly fatigued” and often had difficulty carrying out the simplest of actions on the campaign trail, including flashing his famous victory sign.

But Marcos’ allies insisted he was well, with one Philippine embassy official describing him as “at the peak of health.”

Not in power forever

Ferdinand Marcos was ousted from power via a peaceful revolution on February 25, 1986. The Marcos family and closest allies fled to Hawaii, where they remained in exile for many years.

He never went back to the Philippines alive. The dictator died at the age of 72 on September 28, 1989 in Hawaii – far from the country he and his collaborators destroyed – due to complications caused by kidney, lung, and heart ailments.

In 2006, then-Ilocos Norte representative Imee Marcos confirmed that her father indeed suffered from a “debilitating illness.” It was hidden because advisers did not want to raise doubts about the dictator’s ability to lead the country.

“He didn’t deserve to be confined in his room and make do with the limited facilities of the Palace,” she was quoted in a GMA News Online report as saying. “His attending doctors can’t even bring in the basic medical equipment because of paranoia.”

Marcos’ body was eventually flown back to the Philippines in September 1993 and was interred in a glass crypt in the Marcos Museum and Mausoleum in Batac City, Ilocos Norte.

In November 2016, he was stealthily buried at the Heroes’ Cemetery with full military honors, after a Supreme Court decision sided with President Rodrigo Duterte’s earlier order. (TIMELINE: The Marcos burial controversy)

Many see parallelisms between the past and the present – from human rights abuses to lack of transparency about Duterte’s health.

De Leon said that what Duterte is doing are all straight from the Marcos playbook.

“Ang kapangyarihan ay dapat ginagamit para sa pagsisilbi sa mamamayan, walang sinumang tao ang may karapatan na para bang franchise lang niya, na siya lang ang puwede o siya lang ang habang-panahon na nandyan,” he said.

(Power is used to serve. No one has the right to consolidate as if it’s his own franchise, that he’s the only one who can wield it, or that he’ll forever be in power.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.