SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

It had all the makings of what could have been an inspiring story of Filipinos looking after each other.

In early March 2020, Philippine trade officials saw the shadows of what would become a global shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). So they decided to reach out to local manufacturers to assess whether items like surgical masks and coveralls could be produced for the country.

The idea was to make the Philippines self-sufficient with its supplies of PPE, a highly sought after and precious commodity in the early days of the pandemic. The urgency to secure such items had been felt among health workers reporting a lack of the life-saving items in countries that were the first to experience the toll of COVID-19.

Electronics assembly company EMS Components Assembly was among the Filipino companies to respond when the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) called on select firms to repurpose portions of their factories to produce badly-needed PPE items.

Before the pandemic ballooned into the crisis it is today, EMS chairman and chief executive officer Perry Ferrer and his employees were among those who first experienced the need to wear face masks. This was after the group’s factory in Biñan, Laguna, was hit by heavy ash fall from Taal Volcano’s eruption in January 2020.

Energized by the idea of producing life-saving goods, EMS and five other companies later formed the Coalition of Philippine Manufacturers of PPE (CPMP) to create a new industry just as the pandemic ushered in.

CPMP’s members secured the required certifications from the Philippine government and PPE testing labs in Taiwan to be able to supply medical-grade surgical masks by the end of May 2020.

Despite these efforts by local manufacturers, the Procurement Service of the Department of Budget and Management (PS-DBM), which was procuring on behalf of the health department, largely ignored them.

EMS secured just one contract, worth an initial P1.35 billion for medical grade face masks, throughout the entire pandemic. After lowering its price for masks in February 2021, total actual earnings from the contract fell to P523.5 million. Other CPMP member firms secured a combined P347.2 million worth of orders from the government.

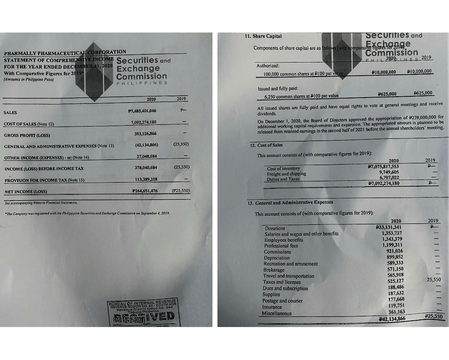

The figures for local manufactures are easily eclipsed by Pharmally Pharmaceutical Corporation, which emerged as the PS-DBM’s favored firm. Congressional hearing have revealed Pharmally won over P8.6 billion worth of COVID-19 contracts despite its lack of solid track record and some of its officials’ links to individuals wanted for financial fraud abroad.

A Rappler investigation also shows how Pharmally, through a network of companies, is connected to President Rodrigo Duterte’s former economic adviser, Chinese citizen Michael Yang.

At a loss

EMS alone had the capacity to provide at least 8.5 million masks per month and had pledged to provide 100 million masks to the government after the PS-DBM awarded it one contract in late April 2020. The company secured its lone contract after it was requested to submitted an offer on April 24, 2020.

EMS is one of the companies that appeared in the Commission on Audit’s (COA) report for selling “high-priced” surgical face masks at P13.50 per piece. But the firm provided the cheapest prices to the government early in the pandemic and later dropped the price for bulk of its shipments to just P2.35 per piece.

EMS, Ferrer said, also sold face masks at a 50% discount from prevailing market prices at the time. The PS-DBM had initially asked EMS to sell the masks for half of what it was worth, adding the government cited doing so would be a “big service to the Philippines.”

Yet days before asking local manufacturer EMS for 50% off, it turned out PS-DBM had purchased some of its most expensive masks from Pharmally, with three orders placed on April 16 and 20. Prices revealed in the COA’s report on PS-DBM showed that for two of its purchase orders to Pharmally on April 16, it paid P22.50 and P27.72 per face mask, respectively, and P22 per piece under the April 20 contract.

Because the health crisis allowed the government to undertake emergency procurement, bidding was not competitive at the time, meaning firms that sought to supply to the PS-DBM were not aware of offers made by other competitors.

“Now that I know [these findings]…it is hard to describe the feeling,” Ferrer said. “At the end of the day, our company, our management team felt negative about it, but we decided, let’s just do it as our service.”

Despite offering the lowest prices to government at that time, EMS also faced difficulties in getting their masks delivered. Ferrer and EMS chief financial officer Luis Lizano said the PS-DBM did not “allow” the company to provide 8.5 million masks monthly as agreed upon.

After the firm was ready to ship out its first batch of surgical masks on June 1, Lizano said the PS-DBM told them to deliver only 5.25 million masks instead of the entire 8.5 million shipment.

The same pattern would hold from June to November.

Deliveries were “really staggered and kept getting delayed. The frustration was very high,” Ferrer recalled. Lizano said EMS reached out to the PS-DBM several times during that period to follow up delivery, but were told that they had “enough stocks” and would check back.

Other reasons the PS-DBM would cite in limiting deliveries was lack of warehouse space to keep the masks ordered or that it was reviewing its inventory for the items, EMS said.

It was only in July 2021 when the firm would finally complete delivery of its 100 million masks to the government – mostly at a loss. Of the 100 million, a fourth or 25 million were supplied at P13.50 from June to November, while the remaining 75 million were provided at P2.35 per piece.

This meant that instead of the original contract to supply 100 million masks at P1.35 billion, EMS ended up selling the total amount of masks for P523.5 million.

The lower price came after the PS-DBM in February 2021 sought EMS to match market prices at the time. Ferrer acknowledged the government had the right to do so but nonetheless described the situation as “painful” since EMS’ deliveries were mostly put on hold despite being ready and available for months.

“It is mind boggling what we lost here,” Ferrer said. EMS likewise has yet to be paid for all its deliveries and was waiting for payment for its final shipment last July.

‘Proud of Filipinos’

What felt inspiring in the beginning now brings some sorrow for local players. In deciding to heed the DTI’s request in 2020, Ferrer and other local firms went all in.

The commitment meant Ferrer would end up investing about P200 million to renovate and prepare parts of EMS’ factory to create a medical-grade production area, which was necessary to produce quality surgical face masks.

For a while, things looked bright. Ferrer recalled the early months of transforming a portion of his factory as one where he felt “proud of Filipinos.”

EMS and other local manufacturing companies were able to source scarce raw materials like filters for medical-grade masks, which were purchased at soaring prices of some $91 to $100 per kilo, far from its current value of about $4.8 as of June 2021.

The firm likewise ordered machines needed to make masks, coveralls, and medical gowns, among others. As soon as equipment for these arrived, foreign technicians from firms where they had purchased the machines could not make their way to the Philippines, but “’yung galing ng Filipino (with the ingenuity of the Filipino) we were able to set up the machine – and run it – without any help from anyone.”

“We Filipinos are capable of producing these items. We created a new industry, and now I feel bad for the other companies,” Ferrer said. “We are a bad example of what could go wrong.”

No capacity?

With congressional hearings placing President Rodrigo Duterte in hot water, the chief executive’s men have been on the defensive, saying the government only gave billions worth of deals to Pharmally because of its “good prices” and ability to deliver within a certain time frame.

After Duterte had ordered the government to secure PPE in a span of days early on in the pandemic, officials had suggested that Pharmally was also tapped because of its capacity to deliver. National Task Force Carlito Galvez Jr. had mentioned in a Palace briefing that about 3 million PPE sets were needed.

The time frame within which the government wanted to have the PPE sets on hand was not clear, by when it came to face masks, the demand could have been covered by local manufacturers.

Publicly available contracts show that one of the earliest contracts awarded to Pharmally was on April 14, 2020, for 2.4 million surgical masks. But less than two weeks later, on April 24, 2020, the PS-DBM sent EMS a request to offer medical-grade surgical masks and signed a contract for 100 million pieces three days later.

EMS, Ferrer said, was also ready and able to provide 8.5 million medical-grade surgical masks per month by the end of May. The figure could have been ramped up to as much as 12.2 million if the government needed as much, he added.

Other CPMP members were also ready to produce medical-grade coveralls by April 13, 2020. Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles, the government’s task force spokesperson at the time, announced that the group had the capacity to produce at least 10,000 coveralls per day. Other forms of PPE, such as coveralls with blue seals, were available through local players by May.

Months later, as Pharmally continued to reap billions from importing supplies for the government, local manufactures were willing and able to supply the needs of the Philippines, CPMP executive director Rosette Carillo said.

In August 2020, the group pleaded with the government to support local firms so that the country’s PPE industry could grow. They pinned their hopes on procurement under the Bayanihan 2 law to level the playing field for them. Significant orders from government could have created about 4,000 jobs and retained some 7,000 workers.

At the time, CPMP was producing 57.6 million face masks monthly, only some 10 million of which were purchased by the government while the rest were exported.

The group was also manufacturing about 3 million coveralls and isolation gowns, which were mostly sold to hospitals including the Philippine General Hospital and the National Kidney and Transplant Institute – which independently procured their own PPE – as well as hospitals in Cebu and Cavite, among others.

Back then, CPMP president Lawrence de los Santos lamented how the government – which has the largest demand for PPE – was still mostly importing these items.

“That is why we repurposed. We heeded the call of [Trade] Secretary [Ramon] Lopez and understand the need of the country…. But at the end of the day, it’s not DTI that buys. It’s the DOH that needs it and they buy presently through the PS-DBM,” De Los Santos told reporters in 2020.

CPMP’s members ended up winning one lot of medical-grade coveralls worth some P170.1 million under Bayanihan 2, Carillo said.

EMS, which had a domestic bidders preference certification, did not win any additional contract to supply the Philippine government with surgical masks. It offered its certified and tested medical-grade masks for P2.6 to P2.35 per piece.

This, despite the PS-DBM saying at the time that it would apply “domestic preference” in the procurement of COVID-19 items.

Meanwhile, data from the Government Procurement Policy Board (GPPB) website showed Pharmally bagged a total of P8.68 billion worth of deals – the biggest among suppliers awarded contracts under the Bayanihan procurement, or procurement for pandemic response, in 2020.

“We keep saying the Philippines is capable in itself to deliver the required and necessary PPE, including face masks, to the government. Kaya ng Philippines (The Philippines can do it). That’s why we scratch our heads, [and wonder] why?” Ferrer said, referring to the government’s seeming preference to import.

Looking abroad

Watching congressional hearings uncover more details of how the Duterte government handled the country’s pandemic funds has left CPMP and companies like EMS pained.

After it was unable to secure enough contracts from the government last year, CPMP member companies retrenched some 3,000 workers by the end of 2020, instead of reaching its target to add about 3,000 to 4,000 new jobs.

“We could have produced excellent quality versus the imports. And it would have preserved jobs and created jobs,” Ferrer said.

After demonstrating the capability to manufacture items like coveralls and various face masks, Carillo and Ferrer said that, in November 2020, the DTI again approached firms, this time to consider venturing into manufacturing medical-grade gloves.

EMS had a partner foreign company that was initially willing to invest about $10 million to produce such goods, but after seeing how local manufactures were treated, Ferrer recalled, “even they (foreign partner) said, ‘You shouldn’t be doing it.’”

Medtecs International Corporation, which has a manufacturing base in the Philippines since 1989, had also wanted to set up a surgical glove manufacturing company in the country, Carillo said. It backed out and the investment instead went to Cambodia.

With little progress in the Philippines, CPMP is now setting its sights on expanding abroad. Among countries that have approached the group include the United Kingdom for possible supplies to its National Health Service. The group was also interested in supplying PPE to the United States.

Maritess Jocson-Agoncillo, executive director of the Confederation of Wearable Exporters of the Philippines – a partner who counts as its members firms in CPMP – said the group was not asking for special treatment from the government, only a fair chance.

“We are willing to bid, but at a level playing field. If they bid it right with the standards in place, the tests in place, the right certificates…and we lose? We are okay, because those standards are what the country needs,” Jocson-Agoncillo said.

The CPMP was still interested in trying to supply the Philippine government with its medical-grade PPE, though it was not able to participate in bids from May to August 2021. Despite this, Carillo added the group would continue to try and supply PPE items to the government.

“During a pandemic, you preserve jobs in the Philippines. You preserve and create employment,” Ferrer said. “This is a global crisis and look at all the other countries, they protect their own, they protect their people.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Under 3 minutes] Did DepEd waste P3-B worth of learning materials?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/titlecard-ls.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=415px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[In This Economy] Brace yourselves for more deficits, debt](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/09/TL-Brace-yourselves-deficit-debt-September-29-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=241px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Beyond infrastructure: Ensuring healthcare access for the poor](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-healthcare-access-03402024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.