SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

READ: Part 1: The OFW debt trap: Less money, more problems

DOHA, Qatar/MANILA, Philippines – Greg* first started receiving threats from collectors of his lending agency 4 months after he returned to the Philippines from Qatar last December 2015.

“Binantaan kami na kung hindi daw kami magbabayad ng loan ay ipapapublish daw ang mga mukha at pangalan namin sa Facebook, TV, at diyaryo para ikahiya kami ng aming mga anak at pamilya,” Greg said. He added, “Sabi niya (kolektor) na masama raw ang ugali namin dahil hindi kami marunong magbayad ng utang at ipinadala rin nila ito sa lahat ng taong inilista namin bilang character reference noong nag-apply kami ng loan.”

(They threatened to post our names and faces on Facebook, TV, and newspapers so we would be humiliated in front of our children and relatives if we did not pay. The collector said we were bad people because we didn’t know how to pay loans and told this to all the people we placed as character references when we applied for a loan.)

Working as a waiter at an Italian restaurant in Doha, Greg is one of the 6,000 Filipinos who leave daily for work overseas.

Had Greg gotten his way, he would have chosen to stay in Qatar. Despite months’ worth of delayed wages coupled with verbal and emotional abuse in his workplace – all came second to a fact: he had a loan to pay.

“Tiniis kong lahat ang ginagawa sa akin dahil alam kong may obligasyon akong binabayaran sa lending,” Greg said in an affidavit. (I endured everything because I knew that I had an obligation to pay back my loan.)

With his salary withheld for months, Greg could not resign to look for another job. Under the kafala system, he would have to secure the permission of his employer before starting an application for other work.

He had heard that there were better opportunities in nearby Dubai, but that would mean resigning plus securing an exit permit from his employer to leave the country – which is not always granted. (READ: How the kafala system enslaves workers in Qatar)

Greg decided he had no choice but to return to the Philippines. And when he did, intimidation, harassment and a mountain of debt awaited him.

Debt bondage

Greg had taken the loan from a lending agency referred to him by his recruitment agency after he informed them he could no longer afford to continue his application to work abroad.

This came despite Greg’s reluctance to pursue work abroad due to financial difficulties that stemmed from his son’s poor health at the time.

“I told them (the recruitment agency) I was no longer interested because I could not afford to pay the placement fee. My son was sick and always had to be brought to the hospital,” he said in Filipino.

Input the total amount borrowed next to “principal”, the number of months given to pay the loan beside “term”, fee prescribed by the loan agency to be paid monthly beside “monthly payment”, and keep “balance at the end of the term” as 0. If no “upfront fees” were paid, keep the value as 0. The calculation will automatically show the monthly and annual interest rate of the loan.

Greg secured a loan of P75,000 to be paid off in one year. According to the terms of his loan contract, Greg was to pay P14,646 in the first month and P10,551 at the end of each succeeding month for 10 months. In effect, Greg’s loan had a monthly interest rate of 9.15% and an annual interest rate of 109.75%, an amount blatantly above the annual 8% allowable by law. (READ: Are zero placement fees for OFWs scam or solution?)

Greg managed to pay off only two months of his loan.

Though no total amount was listed on his payment scheme, documents showed that after just 9 months, he had needed to pay P113,486.56. Just 4 months later, the amount grew further to about P138,967.22 because of high interest rates and penalties.

In most cases, OFWs like Greg are unaware of the soaring high interest rates prescribed on their loans. Incomplete information on payment schemes also leave total amounts to be paid unsaid, making it difficult for workers to compute for monthly and annual interest rates. (To find out what the interest rate on a loan is, refer to the interest rate calculator and input the relevant numbers.)

There are no official statistics but labor rights groups have received many complaints from OFWs involving debt bondage.

According to a working paper from the International Labour Organization (ILO), workers bound for countries such as Hong Kong financed costs largely through loans.

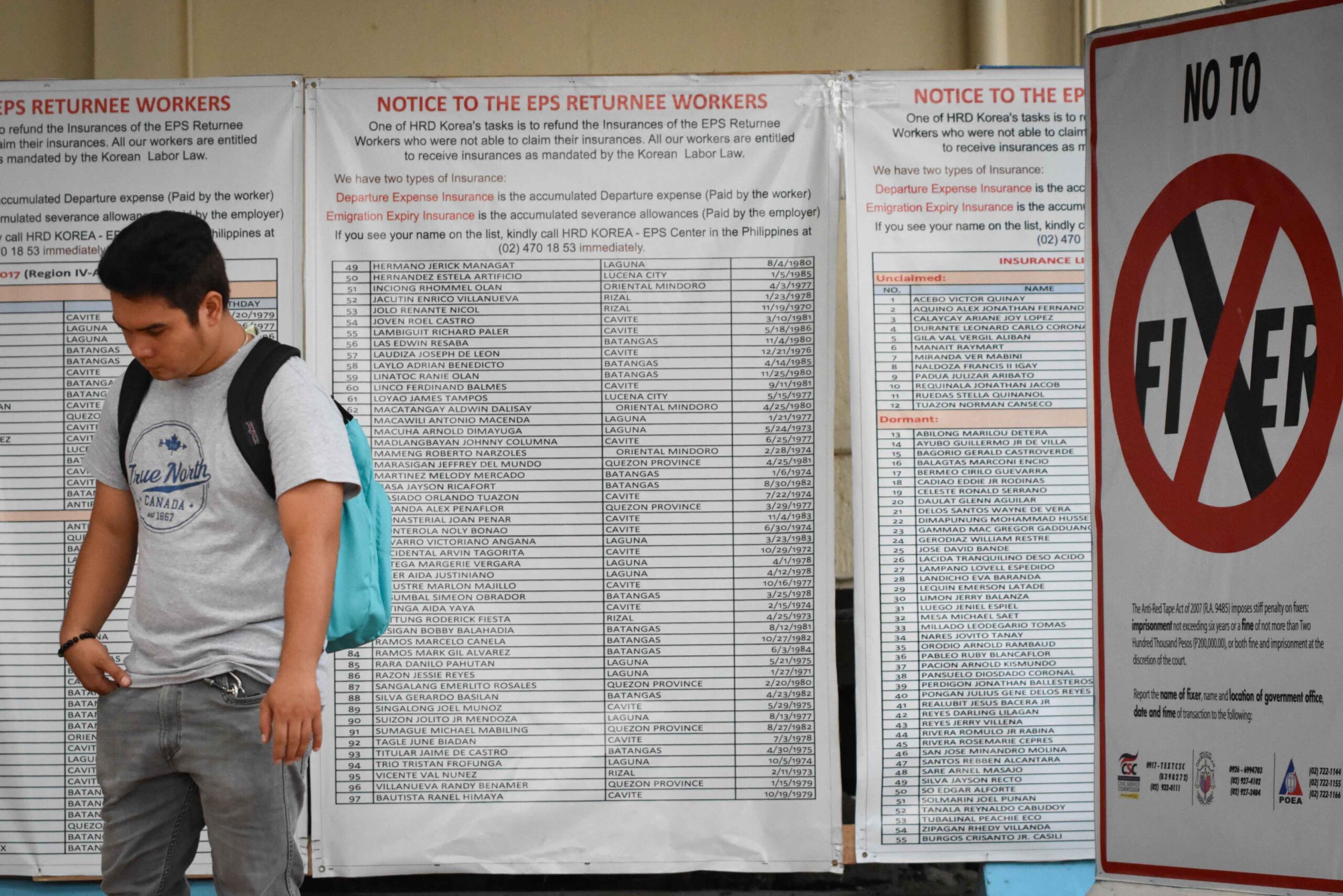

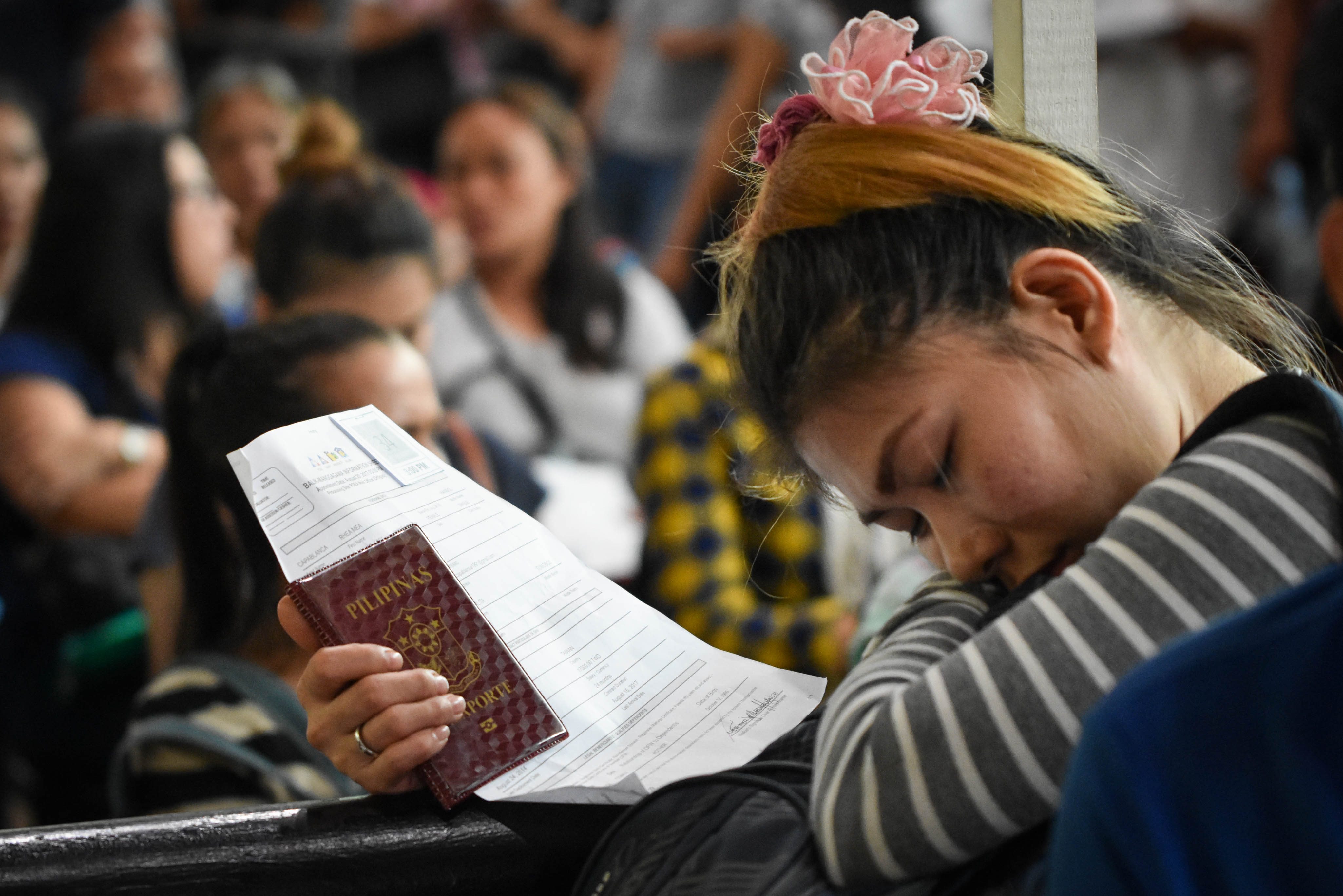

“Although there is little statistical data, previous research estimated that two-thirds of domestic workers in HKSAR, for example, finance their recruitment costs through loans or borrowing…One indicator of the prevalence of loans for jobseekers/workers to finance their recruitment might be the presence of hawkers outside of the POEA, who distribute flyers advertising easy and quick loans to OFWs,” it said.

The issue is also largely undocumented.

Though government statistics show that over the last two years, 358 cases and 3,394 cases of illegal recruitment were recorded by the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) and Department of Justice (DOJ), respectively, these cover all types of prohibited activities in the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act.

Although the practice of giving out loans to OFWs with interest rates higher than 8% is prohibited by law, there are no clear figures on how many cases of illegal recruitment involve such instances.

Statistics from the POEA and DOJ do not separate the count of illegal recruitment cases by specific activity. Instead, cases involving any type of prohibited activity fall under the same category and count of illegal recruitment.

Still unable to repay his loan, Greg’s lending agency threatened him with a criminal case.

With no money saved, he and his wife visited the office of his lending agency in Manila and pleaded for more time to repay the loan.

At the time, Greg had filed illegal recruitment complaints against his recruitment agency with the POEA and planned to pay his loan with the lending agency from the money he would win. However, his lending agency did not agree to this arrangement.

Back and forth arguments soon left Greg and his lending agency on opposite sides. With no agreement reached, Greg also filed a case against his lending agency with the POEA last September 2016. After the lending agency filed its reply with the DOJ in December of the same year, a series of exchanges occurred – after which the DOJ found probable cause for illegal recruitment. Since then, however, no word has been heard from Greg.

Lending without liability

Greg’s case is perhaps one of the few that went as far as the DOJ finding probable cause for illegal recruitment.

But with a system that operates mostly on complaints, the burden to report cases of illegal recruitment is placed on workers. Oftentimes, cases fall through for workers who need to take other opportunities to work abroad.

In other situations, workers may also choose to settle disputes with lending agencies outside of court in an effort to resolve issues quickly.

Lawyer Cora Toldañes of the POEA’s prosecution division said that although the problem is not new, there are hardly any cases where lending agencies are held liable for wrongdoing.

She said this partly stemmed from workers’ unwillingness to see cases resolved. “The worker is not always willing. It’s not just that they are far that they cannot try. Sometimes the worker no longer wants to prosecute the lending agency because he already settled.”

Though Greg initially tried to pursue his case, the lack of government oversight on lending agencies has made it possible to circumvent not only the law, but also liability.

“We have laws but apparently, they have no teeth,” said Ellene Sana, executive director of the Center for Migrant Advocacy (CMA).

According to the Philippines’ Lending Company Regulation Act, lending agencies are under the watch of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). By law, this means that the SEC is tasked to “create a new division or bureau within its control to regulate and supervise the operations and activities of lending companies in the country.”

But for the SEC, oversight and regulation only go as far as ensuring companies comply with reportorial requirements.

For Marie Apostol, senior advisor of Verité Southeast Asia – which pushes for fair labor practices – the current set-up discourages “good players” from entering the labor recruitment industry. “The government applies the same regulations to good players as they would to the bad. They do that to keep the bad players in line but that also keeps good players from entering the industry,” she said.

Oversight

The lack of oversight encourages recruitment and lending agencies to circumvent regulations.

Sana said that OFWs continue to be charged with excessive recruitment fees. And to be able to pay, OFWs apply for loans (which are also connected to the recruitment agencies) at usurious rates.

For instance, Sana said that workers bound for Taiwan practically spend the first 8 months of their contracts paying off debt.

Sana urged the government under the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) to make loans available to workers again to cover not only costs incurred, but also advance family allowances to be given to families left behind.

This OWWA service was suspended and not superseded in the 2016 OWWA act. Currently, there is a pending bill for the credit assistance for migrants which was approved in the House and waiting for its counterpart in the Senate.

But ultimately, Sana said the root of the problem – making workers pay for a costly recruitment process – must be addressed. “Make labor migration process cheap, simple, fast. Make employers pay the costs. OFWs fall prey to usurers, loan sharks, and unscrupulous recruiters because of their desperation to get a job abroad, no matter what.”

She added, “The State should seriously work to create decent job opportunities in the country so that migration becomes only an option or a choice, and not one out of necessity.”

‘We have laws but apparently, they have no teeth,’

– Elle Sana, Center for Migrant Advocacy

Photo by LeAnne Jazul/Rappler

Burdened

In October of 2016, Greg won his case against his recruitment agency.

With an entry of judgment from the Department of Labor and Employment, Greg’s recruitment agency was ordered to pay him his unreceived wages, air fare, and other costs incurred from his job placement in Qatar.

Greg’s case shows that winning cases is not impossible, but the burden of monitoring compliance and initiating redress for violations falls disproportionately on the worker. What has become clear too is that while laws that would prevent migrant workers from falling into debt bondage exist, implementation and clear oversight of all agencies concerned is lacking.

Although the recruitment process is heavily regulated by government, the business of lending money to OFWs to allow them to pay recruitment fees continues to slip through the cracks. Lending agencies are given latitude to set interest rates at unconscionable levels, making it impossible for workers to pay off their loans. Recruitment agencies also know that workers like Greg will still be desperate enough to underwrite their dreams of a better life – even if it means possibly falling into a debt trap. – Rappler.com

*Name changed to protect him from debt collectors’ threats and intimidation.

Interest rate calculator by Dominic Gabriel Go.

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.