SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

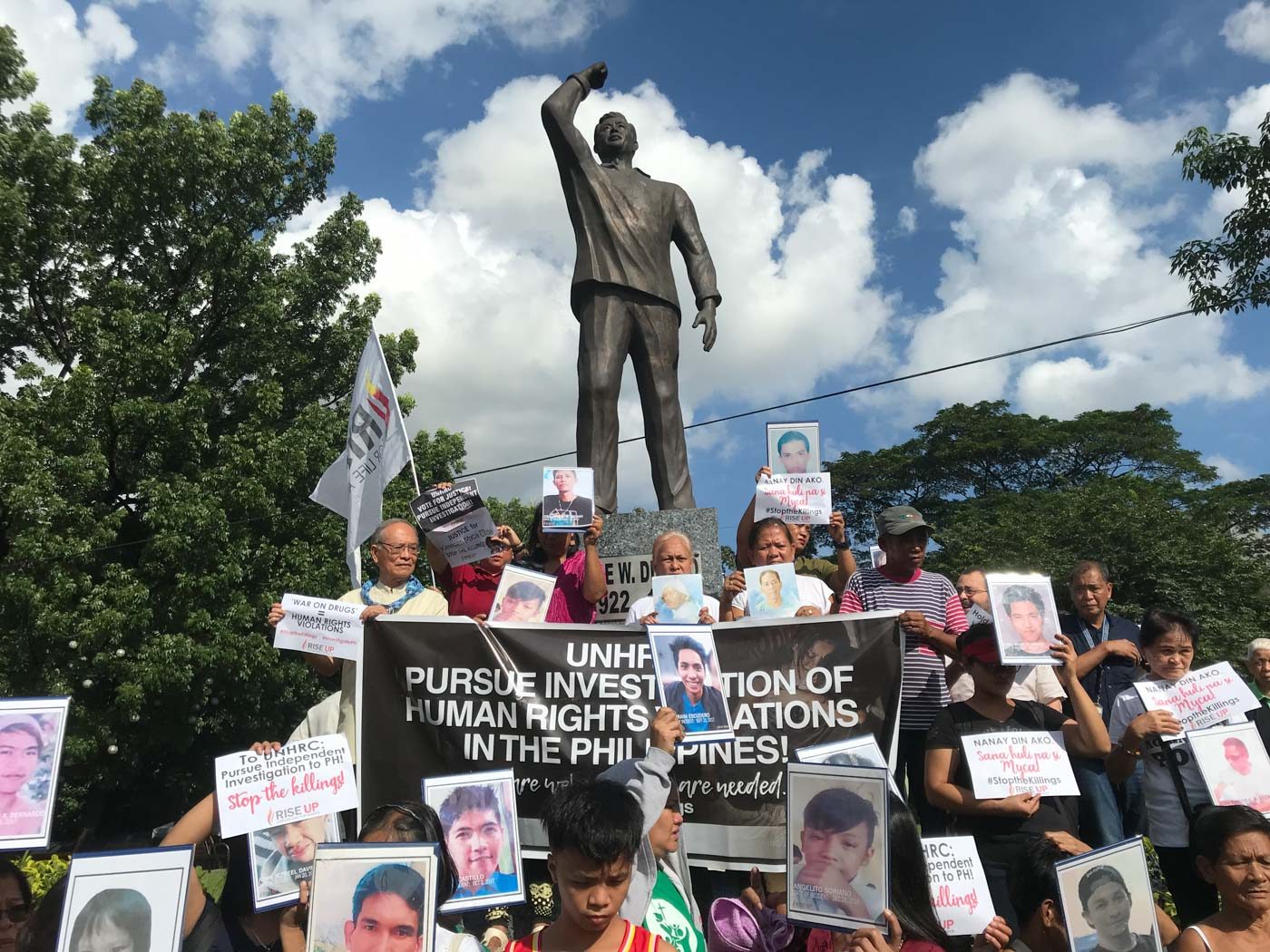

Editor’s Note: Rodrigo Duterte’s violent war on drugs targeted mostly men living in poorest communities across the Philippines. At least 6,252 people were killed in police operations between July 1, 2016 and May 31, 2022, not including victims of vigilante-style killings. This means that Duterte’s flagship project also resulted in thousands of grieving families, including widows and mothers, who are left to balance the role of being homemakers and breadwinners. To mark Mother’s Day on May 14, Rappler speaks to three people to revisit their stories and to know how they navigate their grief following the traumatizing incidents. This series features a mother who lost her son, a widow who lost three loved ones in one night, and a daughter who misses her mother’s guiding light as she raises her own child.

First of 3 parts

MANILA, Philippines – A lot can happen in a month. In Rodrigo Duterte’s Philippines, the passage of time meant more Filipinos killed as his bloody anti-illegal drug campaign raged on.

The night after he was sworn into the presidency on June 30, 2016, Duterte told a crowd in one of the poorest communities in Metro Manila that funeral parlors would thrive under his watch. He promised to order police to ramp up their work if business wanes.

“Please don’t go into drugs because I will really kill you, maybe not tonight or tomorrow, but there will come a day in the next six years that you will make a mistake and I will target you,” Duterte warned in Filipino.

At least 135 people were killed by police in the first two weeks of Duterte’s war on drugs. By July 24, 2016, the death toll doubled to at least 293. This number excluded victims of vigilante-style killings, or those whose bodies were found wrapped in garbage bags or gunned down by motorcycle-riding men.

Pilar* vividly remembered the violence that marred their every day since Duterte took office. Sometimes her family would be sitting inside their house, watching television one late night, and gunshots would ring from a distance. Then there would be news of neighbors, people they’ve known their whole lives, ending up dead either in the hands of police or strangers who lurked in the shadows.

“Kinakabahan ako noon kasi puro patayan na at hindi mo alam kung sino ang isusunod nila (I was nervous because deaths were everywhere, and you didn’t know who they would kill next),” Pilar told Rappler in an interview.

The then-mother of five thought her family was safe. She feared mostly for her friends in their community, not one of her own children. But one afternoon in July, a neighbor visited her home and warned that police were looking for her son Nilo*.

The neighbor urged Pilar’s second oldest son to immediately leave and lie low for a while. She knew all too well what happens when police came knocking on doors. But Nilo protested. He said he was not using illegal drugs, nor peddling them for others to consume.

“Sabi niya huwag kayo mag-alala sa akin, kasi may kakampi raw siya,” Pilar recalled, in between tears. “Tapos tinuro niya ang langit, kakampi raw niya si Lord.”

(He said don’t worry about him, he has someone backing him up. Then he pointed to heaven and said the Lord is on his side.)

Pilar trusted Nilo’s belief that nothing bad would happen. She knew her son well, after all. He worked hard as a tricycle driver to support his children. Pilar said their neighbors loved him too. Nilo had a reputation of going after snatchers and robbers and talking them into returning what they stole. He was so friendly and charming that he always succeeded, to the delight of the people who were victimized.

One time, Nilo saw someone bruised and bloodied on the street. He didn’t know what happened, but he knew the man needed help. He did what he had always done and gave the man money so he could go and have his injuries checked.

“Dapat pangbili niya ng pagkain iyong pera na iyon pero binigay na lang niya kasi naawa siya,” Pilar said. “Ganyan kabait ang anak ko, napakamatulungin.”

(He was supposed to use the money to buy food, but he just gave it because he pitied the man. That’s how kind my son was. He was so helpful.)

Pilar thought: Who could kill someone as kind and helpful as Nilo?

But under Duterte, a person can be included in an unverified list of suspected drug personalities one night, and end up dead the following day.

‘He was begging for his life’

In July 2016, no one would think violence had marred Pilar’s community since Duterte took office. Children were playing on the street under the heat of the afternoon sun, while adults gathered under the shade to gossip. The narrow alleys were alive with either the sound of television sets tuned in on a popular noontime show, or sentimental songs playing from old radios.

A stranger appeared in one corner, followed by a couple more on another side of the block. Within five minutes, the neighborhood was surrounded by alleged police in civilian clothing, ordering residents to go home, shut their doors, their windows, and their mouths. It was not the first incident, nor the last, so residents just followed, fearing also for their lives.

Nilo’s sister, who was caught outside, had no choice but to seek shelter in another house. She had no inkling of what would happen next.

The men knocked on Nilo’s door and told his two companions to leave. Nilo wanted to leave too, but he was blocked by a man who asked his name. Then he asked for his nickname. Then there were gunshots.

Pilar said her nephew who lived in the adjacent room heard everything. Only a thin wall of wood separated the two rooms.

“Wala silang awa, umuungol na nga raw ang anak ko, naghihingalo na, sinabihan pa raw ng pulis na ‘ah nanlalaban ka pa ha?’ Paano pa lalaban kung naghihingalo na?” she said.

“Isang putok na naman at pagkatapos noon, wala na, hindi na narinig ang iyak ng anak ko,” Pilar said.

(They had no mercy. My son was dying, crying in pain, and then the police told him he dared fight back. But how could he, when he was already dying? Then one shot, and after that they didn’t hear my son’s cries anymore.)

Pilar was away working while her son was mercilessly killed by alleged police. She arrived home to a house in disarray and blood on the floor. Nilo’s body was already gone.

At the funeral parlor, they were asked to pay P35,000 for an autopsy. Pilar said they did not have that kind of money, so the owner agreed to a lower amount. In exchange, however, they would have to put sepsis as cause of death in Nilo’s death certificate.

“Pinatay na nga ang anak ko, peperahan pa ako kahit mahirap lamang kami,” Pilar said. “Magulo ang utak ko noon kaya pumayag na lamang po ako.”

(They killed my son but they still wanted to make money from us even if we’re poor. My mind was a mess so I just accepted their offer.)

Nilo is not the only drug war victim whose death certificate carried a false cause of death. Forensic expert Raquel Fortun uncovered falsified death certificates in the course of her investigation into exhumed remains of victims. Families were also forced to lie about the causes of death of their loved ones, a previous Rappler investigation found. The chief of the Philippine National Police’s own Scene of the Crime Operations division agreed with these findings.

Pilar knew it was the police who killed her son. Nilo had not yet been buried when she dared go to a local police station. Ignoring her fears, she went because she wanted answers why her son was targeted and killed.

But the police denied any involvement. Maybe Nilo got caught up in something else, they told the grieving mother. There were other killers on the loose, they said.

“Hindi na rin kami nagsampa ng kaso kasi natakot na ako, ang iniisip ko rin ay iyong mga natira kong anak na lalaki,” Pilar said. “Iniisip ko ang mga kapatid ni Nilo, na baka balikan sila, ayoko naman na mawalan ulit ng anak.”

(I didn’t file a case because I was afraid. I was thinking of my other sons, of Nilo’s remaining siblings who might get killed too. I didn’t want to lose another son.)

Helping others, helping herself

The years following Nilo’s death were a nightmare for Pilar and the family. They already lost their eldest brother years before, and then they lost another. The five siblings were reduced to just three.

Questions clouded their minds. Could’ve they done something to prevent the incident? Nilo’s youngest sibling said his kuya (older brother) should’ve listened when they told him to stay away for a while. Maybe he’d still be alive if he heeded their neighbor’s warning.

The world around Pilar moved on. The surviving siblings focused on their own families. Pilar tried to busy herself with work to forget the pain, but memories of her son always crept back even in the shortest idle moments she had.

In 2019, three years after Nilo was killed, a neighbor asked her if she wanted to join a group composed of families whose loved ones were killed in Duterte’s war on drugs. She was reluctant at first.

“Nakakaluwag sa dibdib ang mga ginagawa namin kasi hindi pala maganda na laging nasa loob ko lang iyong sakit at laging iniisip na walang katapusan ang pagdadalamhati (I realized that it’s not good to just keep all the pain to myself, and to always think that grief is never ending),” Pilar said.

She started just as a participant, a fly on the wall at times, just listening and sharing only if called by facilitators. But as time went by, Pilar said she saw herself engaging more with others.

The grieving mother started leading sessions, and encouraged even more mothers and widows to join their group. During their gatherings, the families left behind learned about human rights that Duterte himself demonized, clearing up previously confusing concepts in the face of massive disinformation on social media.

They also tackled various issues that hound Filipinos, including rising prices of basic necessities. They shared their suffering and pain, but also celebrated small wins together, like a child graduating or a new job being found.

But above all, Pilar learned to handle her pain. She discovered how helping others was also a way to help herself rise above the cloud of grief. She realized she is not alone.

“Nandoon pa rin ang sakit, pero sa pagtulong ko sa ibang nanay, nahihilom kahit papaano kasi hindi na lang ako nag-iisa, marami kaming nagtutulungan,” Pilar explained.

“Akala namin wala nang paraan para sa hustisya, na wala nang tutulong sa amin at habambuhay kami na ganito pero alam namin na makakamtam namin ang hustisya balang araw kahit hindi pa ngayon,” she said.

(The pain is still there but when I help other mothers, I feel some sort of healing because I know I’m not alone. We thought before there would be no justice anymore, that no one would help us, that we would just remain this way, but we know that someday we will get justice, if not now.)

Not losing hope

The grieving families also got together to document what happened to their loved ones. They collected legal documents and helped those who face challenges. In doing so, the families want to make sure that the slaughter of their sons and husbands were put on record and not erased by the powers that be.

Many of these families had communicated their suffering to the International Criminal Court (ICC), an independent body that is now investigating the killings under Duterte’s war on drugs. The mothers and wives know how risky it is, but they know they have to do something since the Philippine government continues to fail to run after those responsible.

Only a few have been convicted in drug war-related killings, including the policemen involved in the deaths of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos, Carl Angelo Arnaiz, and Reynaldo “Kulot” de Guzman.

Pilar hopes that President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. would be different from his predecessor, the foul-mouthed former mayor who had no other solution to societal problems but to kill, kill, kill.

“Ipa-rehab ang mga nakikita nilang may problema sa droga kasi tingnan mo, ang daming pamilya ang nasira at ang daming naulila dahil sa ginawa ni Duterte,” she said.

“Magbabago naman ang mga tao eh para sa pamilya nila, kailangan lang nila ng tulong at hindi dapat patayin,” Pilar added.

(They should just rehabilitate those who have problems with illegal drugs. A lot of families were broken and many were orphaned because of what Duterte did. People will change for their families. They just need help. They didn’t need to be killed.)

For most part, Marcos seems to be deviating from Duterte’s approach, wanting to focus more on prevention. He even said during his US trip that Duterte’s war on drugs resulted in “abuses by certain elements in the government.”

But killings still continue. Dahas, a project of the University of the Philippines-Diliman Third World Studies Center, monitored at least 281 reported drug-related killings under the Marcos administration, as of May 7, 2023. Out of this number, 106 were killed during legitimate government operations.

Marcos is also yet to acknowledge the huge role of Duterte. This is not a surprise given his existing alliance with the Davao-based family. His own vice president, Sara Duterte, is also at the center of a comprehensive network of allies across the Philippines.

Holding the former president accountable is what families like Pilar’s want. Duterte, they said, should be put behind bars and not be allowed to enjoy his retirement. The police won’t have the courage to barge into their homes and kill their loved ones if it weren’t for Duterte.

Families are pinning their hopes on the ICC to run after Duterte. But the Marcos administration is not making it easy for the international court. It has appealed the recent decision of the ICC’s pre-trial chamber that allowed Prosecutor Karim Khan to reopen his investigation into the war on drugs. Several lawmakers also filed resolutions urging Congress to declare “unequivocal defense” of the former president.

Despite these, Pilar remains confident that Duterte and everyone complicit in the bloodbath since 2016 will eventually be held responsible, and that they will someday have their day in court.

Giving up is not an option for the drug war families. They already lost their loved ones, they will not allow the government to take away their only hope for justice too.

“Mananagot ang mga gumawa ng kasamaan sa aming mga mahal sa buhay kasi bilog ang mundo,” she said, adding, “Inalagaan namin at pinalaking maayos ang aming mga anak, tapos ganoon lang nila kukunin ang buhay nila? Papatayin lang nila na walang awa?”

(Those who did evil things to our loved ones will eventually be held responsible. We know it. We cared and raised our children well, only for them to get killed just like that? Killing without mercy?) (To be continued) – Rappler.com

NEXT: PART 2 | Drug war widow: I must fight for my child, grandchildren

*Names have been changed for their protection.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[EDITORIAL] Sorry Arnie Teves, walang golf sa kulungan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-arnie-teves-arrest-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=310px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler’s Best] Patricia Evangelista](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/unnamed-9-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=486px%2C0px%2C1333px%2C1333px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.