SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The discussion around online class has sparked a lot of controversy. Students without good resources or access like Franz Berdida and Kriselyn Villance, must go to extremes to keep up.

The issue of online classes is one about access. More broadly, it is about the education system, and the problems that hinder us from making online classes a reality. The pandemic has also highlighted the need to improve the education system, and presents an opportunity to do so.

This analysis looks at the current education system’s situation, and gets two experts’ insights on ways it can be improved. Love Basillote is the executive director of Philippine Business for Education (PBEd), a nonprofit researching learning methods during the pandemic. Mike Luz is the dean of the Center for Development Management and a former Department of Education (DepEd) undersecretary.

To limit the scope, the analysis focuses on the National Capital Region (NCR), and compares it with the neighboring province of Cavite – which despite their geographic proximity, were later on found to differ in some key areas of education.

If we stop class, what’s at stake?

An expert says reopening class will have its inequalities, but stopping class will worsen inequality. Given that online classes will be difficult for many, stopping class may seem like the most immediate option. If this happens however, what’s at stake?

Basillote said that when students stop schooling, they are less likely to return to school – compared to if they had not stopped. Also, the probability of youth succumbing to crime and teenage pregnancy increases when they are not in school. In other words, stopping class comes with both social and economic consequences that hamper students’ long-term growth.

Sadly, whether or not schools reopen, rich students will still have resources to keep learning, while the poor will get left behind. According to her, this is where the government comes in – to direct resources to those who need it most, to ensure that poor students do not get left behind.

If classes should continue, what must be in place for online classes to work?

For context, online class is not the only method being proposed. There are digital and print modules, and TV and radio learning. But if online classes were to be implemented for all, what factors must be in place to make this work? The experts identified 4 key elements.

It’s worth mentioning that DepEd, local government units (LGUs), and other organizations have already been working to make sure the elements identified by the experts as necessary are within reach. Nonetheless, this article aims to identify what concrete actions can be taken to make online learning work.

Infrastructure: Wi-Fi, signal, devices, and alternatives

Among the 4, infrastructure is probably the weightiest issue. When businesses are closing and jobs are being lost, online classes pose another expense to already struggling families. To understand how many students would be affected, the analysis looked at poverty in NCR and Cavite.

In NCR, online classes will pose a challenge to the 105,000 students who live in poverty

A UP study (2020) estimates that elementary students will attend one to two hours of online class daily, while high school students will do 3 to 4.5 hours, with data costing P13.50/hr. Unless government can provide, families must shell out extra for devices, given DepEd’s requirements.

Put together, families are looking at upwards of P12,000 for a laptop, on top of P300-P500 (elementary) or P800-P1,200 (high school) per month for data. This may easily double for families with two children – which is common in the country.

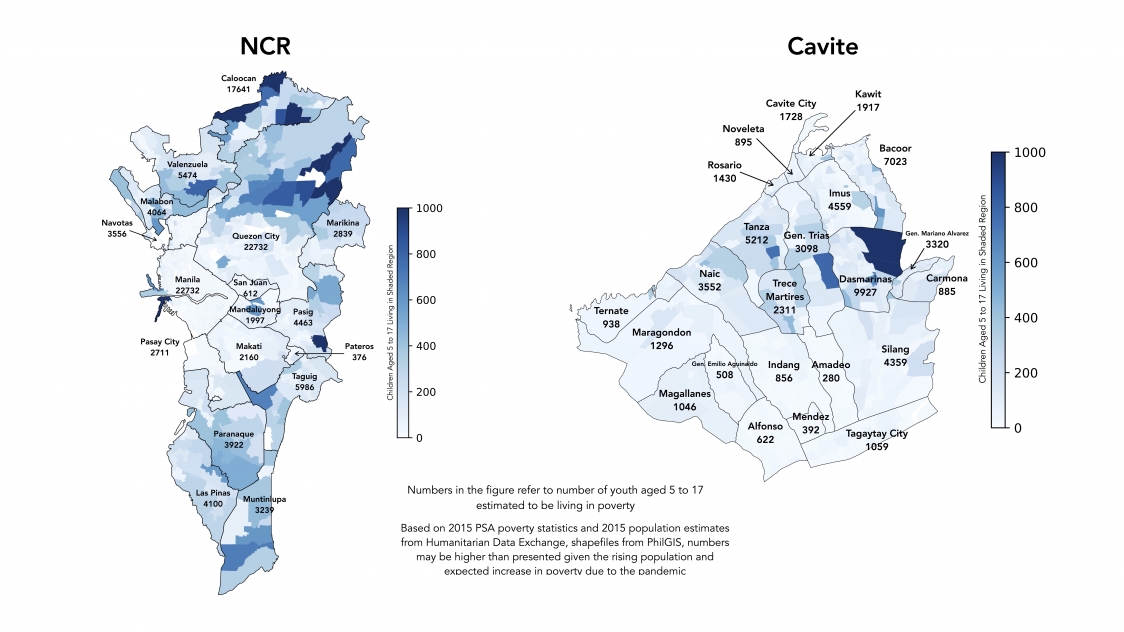

This will pose a challenge to the 105,000 students in NCR, and 55,000 students in Cavite who live in poverty. This was calculated by multiplying 2015 municipality level poverty by 2015 municipality population estimates of elementary and high school-aged youth (5-17 y/o).

Imagine – in 2018, a family earning P28,000 a month in NCR and Cavite was deemed as living below the poverty line. Considering the monthly cost of data and a device, on top of rent, food, and basic utilities – it is simply not enough. Having to purchase a low-end laptop would already eat up almost half of a family’s monthly earnings.

The maps below show the number of students living in poverty by barangay, and a total for each city. While NCR and Cavite have poverty incidences of 1.4% and 3.7%, respectively, imagine how it might be for provinces like Eastern Samar or Maguindanao, where poverty is at around 40% (2018)?

Quick reality check

Doing the math, a laptop and 9 months of data would cost around P15,600 for an elementary student, and P21,000 for a high school student. If DepEd subsidized this for the estimated 57,000 elementary and 49,000 high school students living in NCR, this would amount to P1.91 billion. By similar calculations, it would cost P1.03 billion to cover students in Cavite.

What does this mean? Shelling out billions for multiple provinces will make a dent in DepEd’s budget – but given that the department received P551 billion in the 2020 budget, there is money to move around. This, however, would take from the budget allocated for school repairs, student assistance, feeding programs, and teacher hiring and training – a hefty choice.

DepEd must step up to provide, and ensure that alternatives are accessible

To push online classes, people need devices, stable connection, and data. But in far flung areas like Davao de Oro where internet is scarce, this is difficult. DepEd is responsible for pooling and distributing resources, but help can come from many places. Companies can donate old laptops, personalities can inspire action, government offices and nonprofits can collect and refurbish devices – all of which are already happening. But the country needs more.

For areas where online classes are not possible, planners must ensure that alternatives work. Basillote said that for students using modules, they need ways to ask questions and get answers, whereas Luz pointed out that students living far away must access education too.

When thinking about accessibility, planners must remember remote areas

DepEd has plans in the works to deliver materials to students, or have parents pick up materials from nearby. When rolling these plans out, officials must not forget those who need them most.

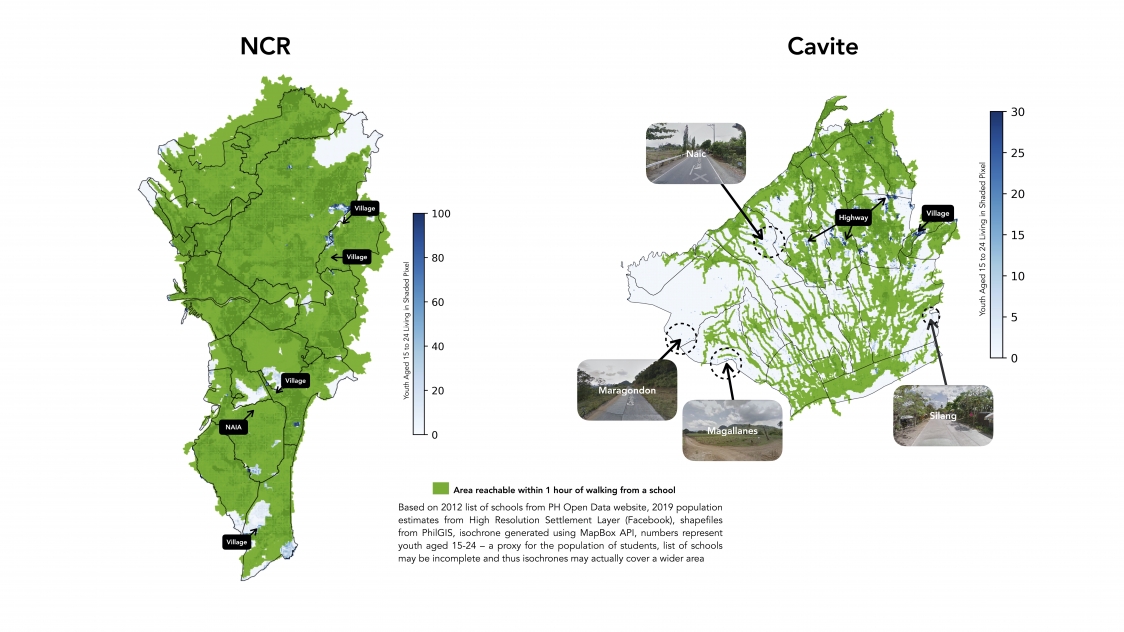

The Facebook High Resolution Settlement Layer (HRSL) was used to map out where youth live. Schools were located from the Open Data lists and geotagged. Finally, Mapbox was used to generate isochrones – areas reachable from schools within one hour of walking. Note: 2012 data was used, so results should be taken with caution.

The contrast between NCR and its neighboring province of Cavite is stark. In NCR, nearly all populated areas are within a one-hour walk from a school – with the only exceptions being villages – where people presumably have resources for online class.

In nearby Cavite however, there are small areas, often mountainous or remote, in Maragondon, Magallanes, Naic, and Silang, which are well out of reach from schools. Given such big differences, planners must study the situation in different areas in depth, to ensure that even the most remote of places are taken into account.

Curriculum: Less topics, more quality

Basillote broke down the curriculum into two parts: academics and soft skills.

On academics, Luz said DepEd must reduce the number of topics and focus on quality. Prior to COVID-19, countries topping international tests already had short curriculums. Per subject, students learned 8 to 10 topics a year, giving them 3 weeks to master each topic.

In comparison, he said the Philippine curriculum tries to teach too much. As a result, students cram a lot of knowledge without sufficient mastery. Especially at a time when students are under a lot of pressure, trimming the curriculum is crucial. DepEd produced a trimmed curriculum for the coming year, reducing the total competencies across levels K to 12 from 14,000 to 5,600.

While academics can be learned using modules, soft skills cannot. Basillote said this is where teachers come in. With the distance learning setup, teachers’ roles shift from giving lectures to guiding students. With this, she said, teachers can focus on promoting soft skills – like empathy and regard for mental health, through discussions and mentorship.

Teachers: Adapting to a ‘new normal’

The distance learning setup forces teachers to adapt to a new way of teaching. In 2018-2019, a teacher handled 29 elementary students on average – though this figure is likely much higher in other schools. If handling 29 children in person was not hard enough, imagine keeping all 29 attentive on a video call. These are some changes brought about by the new normal.

First, teachers will need to learn online tools – Zoom, Hangouts, groups, whiteboards, etc.

Second, teachers need to adapt to teaching online – by finding alternatives to lectures and ways to keep students engaged. Luz said flipping the classroom – letting students self-learn then share what they’ve learned – is an effective way of learning being explored by a school in Bohol. Organizations have also begun sharing resources for teachers adapting to the new normal.

Teachers will also need to come up with assessments that consider the limits of their students’ resources, while still maintaining integrity and preventing copying of work from afar.

Finally, teachers need to do all this while maintaining empathy for their students and adjusting lessons and work, given the students’ situation – not to mention their own. It is no easy task.

Basillote pointed out that distance learning also requires parents to become more involved in their child’s education. From setting up the technology, to guiding children through modules, to coordinating with teachers, parents will also require orientation and resources from DepEd.

A teacher’s perspective

A teacher at a government school in Quezon City said this new normal poses big hurdles. She has been spending her summer preparing 4 modes of learning – live online classes, recorded videos, digital modules, and print versions. This takes her thrice as much time for preparation – for teachers who are less tech-savvy or in schools with less resources, it may take even longer.

Although these alternatives are necessary, she is apprehensive about the quality of learning these provide. Modules feed information, but they don’t allow students to ask questions or get feedback. Moreover, she fears that teachers are spreading themselves too thin preparing the alternatives. Without good data on which modes students will use, it’s hard to focus on one.

Despite this, she believes that learning must continue in some form. Completely stopping gives richer students the opportunity to “get ahead” while the poor fall behind. She said each year not in school is a missed opportunity, and learning is crucial to a child’s growth and mental health. Thus, she said, educators owe it to students to provide opportunities to continue learning.

This underscores the need for change. First, she said policy makers must be better at listening to the teachers on the ground. The burden of “making things work” often falls on their shoulders, and they are the ones who can best determine what is working, what isn’t, and how to improve.

Second, she said teachers must look for new, more equitable ways of conducting assessments. The system has a fixation with tests, and she said the discussion among educators has largely revolved around how to prevent students from cheating in online classes. The conversation must shift to finding new assessments that students can do given the limited resources.

Finally, she said the government needs to solve this health crisis. Remote learning was never built to be a method of learning for all – and the current setup is unsustainable in the long run.

She added that DepEd has the tall order of keeping students in school during a pandemic – but without normal classes, every alternative is at best a temporary solution.

Community: The people on the ground know best, let them decide

During a pandemic, local information and resources are necessary. A one-size-fits-all solution is not enough – what works for a COVID-19 hot spot like NCR might not work for places with barely any cases.

Basillote and Luz agreed that the situation must be assessed at the local level, and that LGUs should be able to decide for themselves.

Luz wants normal in-person classes to resume in areas with no COVID-19 cases, especially for younger students. Children their age are learning to socialize, and experts write that when schools are closed, they miss out on a crucial point in their development.

Will this work?

Basillote said it’s all in the execution. This is a new situation, and the short answer is that experts have no clear idea how it will go.

What she does know however, is that promoting online classes alone will not improve the situation – it takes planning, coordination, and good people at all levels of the system. The pandemic presents an opportunity to fast-track reforms – changes that might take place over years now happen within weeks.

The time is ripe for change. With classes opening in August, the government must act fast, while getting input from teachers in the field and working with local partners – so that we come out from COVID-19 with a better education system for all. – Rappler.com

Lj Flores is an intern at Rappler and a student at Yale University studying statistics and data science.

Made in partnership with TheNerve, a Manila-based consultancy that specializes in bringing together valuable data insights and meaningful narratives.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.