SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The pandemic did not dampen the resolve of student activists to demand accountability from government over the worsening situation of the education sector.

“We lack investment in the education sector that’s why when the pandemic came, we are struggling. You can’t deal with the problems of decades of underfunding in one day and now we’re experiencing the deficiency of underfunding. It’s decades of problems catching up now,” said John Lazaro, national spokesperson of Samahan Ng Progresibong Kabataan (Spark), in an interview with Rappler on Monday, November 30.

This time is really difficult for education. It’s a result of decades-old underfunding and inefficiency in the education system.

John Lazaro, SPARK spokesperson

Spark is a youth group composed of at least 300 members which aims to “unite the youth to realize its integral role in shaping history by linking it to the struggle of the marginalized sectors of society.”

Due to the continuing threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, students in the country were forced to attend classes remotely. This sparked a heated debate owing to problems pertaining to connectivity and gadgets. (READ: No student left behind? During pandemic, education ‘only for those who can afford’)

A student activist for over 3 years now, Lazaro said that as the country commemorates the 157th birth anniversary of Andres Bonifacio – founder of the revolutionary group Katipunan – they are taking their voices to the streets to call out government inaction on the problems students are facing.

“I would say that this situation requires us to be critical of what’s happening now in our social movements and in our politics and also to decide to take action. We cannot just sit and talk about Bonifacio because he’s dead, right? It’s the time for us not just to commemorate his memory, but to take action,” he said.

Lazaro said that the Filipino youth have exhausted “all means of diplomatically holding the administration accountable” for its handling of the pandemic, disasters, and the woes stirring the education sector. They are determined to take concrete action, including the launching of student strikes.

Problems in education

While the education sector would always receive the lion’s share of funds in the government budget, the amount being allocated has not been enough to cover the needs of Filipino students. (READ: [ANALYSIS] Why you should be alarmed by Duterte’s 2021 budget)

Even before the pandemic, classroom shortages would always greet students whenever school opened. A class of 75 to 80 had to squeeze themselves into one classroom supposedly fit for a class of only 40. To make up for the lack of classrooms, class shifting had been implemented to accommodate enrollees every year. (READ: Classroom shortages greet teachers, students in opening of classes)

In the 2021 budget, only P15 billion was allocated for the printing of learning modules for the distance learning system. But think thank Institute for Leadership, Empowerment, and Democracy (iLEAD) estimated that about P67 billion is needed for the production of modules for over 20 million public school students this school year.

The Department of Education (DepEd) said that due to the lack of budget, students would have to share learning modules. However, teachers and parents raised concerns over the rotational use of modules due to fears of contracting the coronavirus. (READ: Is it safe? Teachers fear exposure to coronavirus in modular learning setup)

“The additional cost of modular learning shouldn’t be borne by the parents of students because many of the students belong to low-income families who are already suffering because of the protracted COVID-19 crises and in some places, the consecutive typhoons that happened recently,” said iLEAD executive director Zy-za Suzara.

Student protest

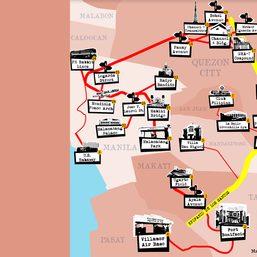

On Monday, November 30, students converged at Morayta corner Recto Avenue before proceeding to Mendiola Bridge, and staged a protest at the University of Santo Tomas to slam the Duterte government’s handling of the transition to distance learning, the pandemic, and its disaster response.

Students from Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU), who launched One Big Strike, called for a nationwide academic strike on November 23 and demanded accountability from the Duterte government for its “criminal negligence” during the recent typhoons and the COVID-19 pandemic. (READ: Ateneo students call for nationwide academic strike vs Duterte gov’t)

“This all comes from the incompetence of our government and their lack of response to both the pandemic and the typhoon. This is not just an issue of the education sector, but an issue of society as a whole. There are people who lost their jobs,” said Bern de Belen of One Big Strike in an interview with Rappler on November 24. (READ: Unemployment down to 10% in July 2020, says Philippine gov’t)

The pandemic caused the unemployment rate to spike to 17.7% in April 2020, the highest unemployment rate since the earliest comparable data in 2005, based on available data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). This is more than triple the 5.1% unemployment rate recorded in April 2019. (READ: In Duterte’s 4th year, COVID-19 causes highest unemployment on record)

While the unemployment rate in the country eased to 10% in July from 17.7% in April, around 4.6 million Filipinos remained jobless, the PSA said.

Tired of government inaction, De Belen said they are taking their voices to the streets because they feel “unheard.”

“Maybe doing an academic strike and boycott will make the government listen to us,” she said.

On Monday morning, various organizations from the labor sector, such as Kilusang Mayo Uno and Tambisan Sa Sining, and several youth groups converged along University Avenue to defend the rights of Filipino workers and call for the junking of the anti-terror law.

Calls for an academic break resurfaced after consecutive typhoons battered the country in the past weeks. This affected students’ access to education due to loss of electricity, internet connection, and the destruction of their homes.

Both the DepEd and Commission on Higher Education (CHED) dismissed calls for a nationwide academic break – or the suspension of classes for a certain period.

CHED said it won’t issue a “unilateral” suspension of classes in the country because “different schools and different families are affected differently.” Meanwhile, DepEd said that a break would have a “massive impact” on the lives of students “economically.”

Protest in the time of a pandemic

Lazaro said the pandemic has made it difficult for student activists like him to organize protest actions due to the safety precautions they need to consider, which need month-long preparations.

“Because of the restrictions, we cannot do anything fancy and grand. But in this time and age, marching on the streets is a big thing,” he said.

According to Lazaro, preparations include include logistical concerns, securing protest permit, negotiations with the police, and communicating with parents to allow their children to participate.

“You have to think out of the box given the pandemic restrictions. You have to plan for social distancing because it’s not simply marching on the streets, but we have to carry placards with the right messaging. You have to come up with a catchy slogan,” he added.

But on top of it all, safety and health concerns are still a priority.

“The pandemic made it difficult for us to organize people. It’s harder to get people on the streets because transportation for some, especially those who live far from the protest venue, is difficult. And some are living with vulnerable family members. For those cases, we are discouraging them to participate,” Lazaro explained.

Fear for life

Lazaro said that being an activist entails security risks because basically they are fighting with government and opposing its “anti-people” policies.

“With regards to security concerns, it’s very tough for me. I have to take a lot of safety precautions,” he said.

Lazaro said that he has to keep his social media accounts private to avoid attacks from government supporters.

“I have to be very careful with the things I do on my social media. You know as a spokesperson, I’m very private with my social media which is very weird. The only time you’ll find me talking is in my capacity as a spokesperson,” he said.

Red-tagging

A very real danger is being red-tagged by elements of the military who consider communists as enemies of the state. Yet communism is legal in the Philippines after Republic Act 1700 – a law signed in 1957 to counter the anti-Japanese-turned-CPP-armed-wing Hukbalahap – was repealed by RA 7636 in 1992. This ironically happened under the administration of former president and former Armed Forces chief of staff Fidel V. Ramos when they began peace talks with the Communist Party. (READ: ‘Mas dapat magalit’: Filipino youth face dangerous future with anti-terror bill)

Being red-tagged, regardless of the medium, does not end with arrests. It carries greater threats in the context of the anti-terror law. For many activists, it has even cost them their lives – National Democratic Front consultant Randy Malayao, agrarian reform advocate Randy Echanis, human rights activist Zara Alvarez, and just recently, the daughter of Bayan Muna Representative Eufemia Cullamat, Jevilyn Cullamat.

According to human rights group Karapatan, at least 167 have been killed since 2016. The killings exist alongside the thousands also slain under President Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-illegal drugs campaign – all part of the culture of impunity he has encouraged.

In the first month of 2020 alone, at least 3 peasant organizers were killed, allegedly by state agents.

To be safe, at least from attacks on social media, Lazaro said he keeps a lot of space between his personal life and his role as an activist. “But of course, personal is political,” he added.

Why student activism is important

Professor Jayeel Cornelio, ADMU director of Ateneo’s development studies program, said that student activism is important because it is a platform for the underrepresented sectors of society to air their grievances.

We need alternative voices to discern the best way forward. This can sometimes come from the most affected communities.

Professor Jayeel Cornelio, ADMU director of Ateneo’s development studies program

Cornelio added, “These are the voices that policymakers don’t often get to listen to because they are not directly connected.”

But Cornelio was saddened by the fact that students have to resort to an academic strike because they are not being heard. (READ: School time out during a pandemic? Pros and cons of an academic break)

“This democratic participation inspires conversation. Sometime successful, sometimes not,” he said.

Student activism is not only happening in the Philippines. In Hong Kong and Thailand, for example, both saw their streets fill with protesters daring to take on an entrenched political elite, and discussing once-taboo subjects in their push for greater freedoms. (READ: Young and restless: Protest parallels in Thailand and Hong Kong)

For Lazaro, students should not see education as merely schooling as they also have to reflect on the society they are a part of.

“Students cannot be separated from society. Students have to join other sectors, they have to learn from other sectors. They need to talk to the labor sector, the LGBTQ+ community, to the farmers so we could gain an education that schools could not provide us. This is the time for us to learn,” Lazaro said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.