SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Of the many issues to hit the Duterte presidency, one of the most resounding and enduring are the allegations of human rights abuses, and at the front row of the accused are the members of the Philippine National Police (PNP).

The PNP has been the preferred instrument of Duterte in enforcing his law enforcement campaigns. Most muscle and cash have been poured into Duterte’s popular but bloody centerpiece campaign, the war on drugs, and the broader campaign against criminality.

As the world declared lockdowns, the PNP took centerstage to implement the laws, with Duterte as their main cheerleader, again leading to more allegations of human rights violations.

Despite its tainted record, the PNP, in fact, has an office that was created to declare its own war, but against the rights abusers within the organization: the PNP Human Rights Affairs Office (HRAO).

The HRAO was created in response to allegations of extrajudicial killings during the time of President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. It was envisioned as “a management facility to oversee the implementation of PNP guidelines and policies on human rights laws.”

“Gustong-gusto rin namin malinis ang hanay namin against abuses, against scalawags. Gustong-gusto namin malinis, gusto namin maging perfect ‘yung aming organization, na walang iisipin kundi pagsilbihan ang mamamayan,” HRAO acting chief Colonel Vincent Calanoga told Rappler.

(We want to cleanse our ranks of abuses, of scalawags. We want it clean, we want our organization to be perfect, one that thinks only about serving the people.)

Rappler spoke with police involved in implementing the vision for HRAO, along with human rights workers and experts on the office.

Over a decade later, it has been assailed for its lack of power and effort – often limited to internal human rights campaigns only – to keep up with the breakneck speed with which allegations of rights violations arise in the Duterte administration.

The roots of the rights office

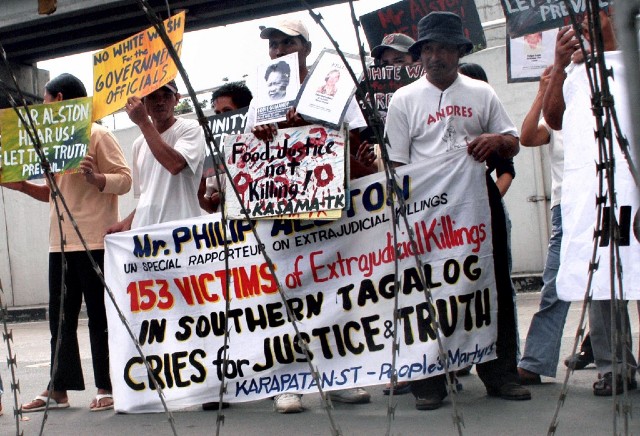

It was 2007. Two probes established a pattern of extrajudicial killings linked to the Philippine military. The first was by then-United Nations Special Rapporteur Philip Alston, which resulted in what is now famously called the Alston Report, and the second, by then-Supreme Court justice Jose Melo, who led the popular Melo Commission.

According to the Alston Report, there were some 10 complaints alleging extrajudicial killings filed with the police. Only two of them made it to the prosecution, showing government inaction and the fear of witnesses to step forward.

“There is impunity for extrajudicial executions. No one has been convicted in the cases involving leftist activists, and only 6 cases involving journalists have resulted in convictions. The criminal justice system’s failure to obtain convictions and deter future killings should be understood in light of the system’s overall structure,” Alston said in his report.

He also took a swipe at how the PNP was complicit in the process, saying: “Crimes are investigated by two bodies: the PNP, which is organized on a national level but is generally subject to the ‘operational supervision and control’ of local mayors; and the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI), which is centrally controlled.”

The Melo Commission, meanwhile, found that many extrajudicial killing complaints did not lead to convictions because witnesses were afraid of government’s uniformed personnel.

“There is lack of confidence in the impartiality of police, fear of reprisal by other elements of society, and lack of interest of the victims’ families,” the Commission’s report said, citing then-police chief Avelino Razon.

Both Alston and the Melo Commission recommended that the police and military bolster their investigation into the killings and to promote human rights within their organizations.

It was in the spring of reforms from the recommendations of these two commissions that the PNP HRAO was born on June 29, 2007, through a resolution by the National Police Commission.

The mandate and its limits

The PNP HRAO was given 5 orders:

- Integrate PNP efforts and come up with a holistic approach and systematic implementation of human rights programs and activities

- Review, formulate, and recommend policies and programs, as well as administrative and legislative measures to effectively implement human rights laws

- Monitor the conduct of investigation, legal, and judicial processes of addressing human rights violations of PNP personnel

- Undertake information campaigns to project government findings and measures implemented in relation to human rights violations of PNP personnel

- Connect with agencies related to human rights violation probes against the PNP

The first 3 concern the PNP HRAO’s role in policy-making as a research office for human rights violations committed by the PNP.

One of their most prized achievements in line with this mandate is the publication of the PNP’s guide to rights-based policing, which compiles international and local standards for upholding human rights.

The 4th mandates transparency of the office. The PNP HRAO, however, has not been publishing data and information about the PNP’s alleged violations of human rights.

Rappler requested for data from the office, even complying with the PNP’s freedom of information request form, but they only shared a copy of the Duterte government’s outdated and publicly available #RealNumbers counting initiative.

The PNP HRAO’s last mandate paints a picture of inclusive investigations into violations, but the office is still restrained by its own place within the PNP system.

Even the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), which the PNP HRAO has a more “open” engagement with compared to the whole PNP leadership, cannot tap the office when it comes to case folders and documents of thousands of suspected drug personalities killed in Duterte’s violent campaign against drugs.

While the Commission sometimes courses its request for follow-up information on cases it is investigating through the PNP HRAO, it understands that the office’s power is also limited.

“Meron talaga silang limitations, given na kung nasaan sila sa PNP hierarchy,” CHR Commissioner Gwen Gana told Rappler on November 17. “Parang hindi rin transparent ang [other PNP offices] sa isa’t isa, I don’t think they share information even with PNP HRAO.”

(They have limitations, given where they are in the PNP hierarchy. It’s like they’re not transparent to each other. I don’t think they share information even with PNP HRAO.)

The PNP HRAO has no power to investigate human rights abuse cases. If someone accuses police of abuse, the HRAO will simply refer that person to police investigators.

“You can go to HRAO but we will refer you to the appropriate unit to investigate the complaint,” acting HRAO chief Colonel Vincent Calanoga told Rappler in an interview. “We have no mandate to investigate human rights cases, only to monitor.”

Calanoga also does not believe that their agency needs more teeth, because according to him, the PNP is already doing enough to weed out the policemen who commit human rights violations.

“The PNP does not sleep on, and they do not tolerate, misdemeanors in the organization,” he said.

The reality on the ground indicates otherwise. Under the Duterte administration, many cops remain unscathed despite allegations of abuse. In the violent war on drugs, only 3 policemen involved in the killing of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos have been convicted so far, despite the thousands killed.

For National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers president Edre Olalia, there is little evidence that shows the PNP HRAO is an effective office.

“It was nonexistent, let alone did its job,” he told Rappler on Wednesday, November 25. “If at all, it was for show as far as the victims of human rights violations are concerned.”

Karapatan secretary-general Cristina Palabay, meanwhile, said that they are not aware of any “substantial leap” in how the PNP HRAO cascades human rights law into guidelines and policies within the PNP.

“What is apparent is how PNP compliance [with] international and national human rights instruments has gone downhill, especially in the past 4 years,” she said.

Duterte sabotaging HRAO’s mandate?

With its limited mandate, the PNP HRAO focuses on seminars to train policemen on human rights and to inform the public about their right to complain against their abusive colleagues.

The PNP HRAO partners with the CHR for these training on human rights.

In 2018, at least 20,282 personnel from the PNP and Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) underwent human rights training. In 2019, CHR trained 27,467 people from the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), Philippine Public Safety College, and other agencies in the security sector.

The topics discussed range from basic human rights concepts such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Bill of Rights under the 1987 Philippine Constitution, to the more in-depth concepts like human rights-based policing.

“They usually have questions on how to treat suspects, the rights of suspects, and even what are included in the police manual,” CHR Commissioner Gana said. “They have to be reminded of these things, it’s all part of what a policeman should do in upholding and protecting the rights of the accused.”

Mi-an Taglucop, an information officer in CHR CARAGA for 3 years, told Rappler that training cops requires strenuous effort to transform the mostly technical or complex human rights instruments into easily understood terms.

As the region’s few training specialists, she has led human rights seminars and training workshops as part of the PNP’s Public Safety Basic Recruit course. She also handles the human rights portions of various courses crafted for both junior and senior police officers in the region.

“Ipapakita mo iyong concepts ng [human rights] na angkop sa kanila, iyong makikita nila sa local context, iyong posibleng na-witness na nila o naranasan,” she said. “Sa ganyang paraan, nasi-simplify iyong discussions at mas fruitful din.”

(You present the concepts in a way that’s appropriate to them, mostly in the local context, or through examples that they probably witnessed or experienced already. In that way, the discussions are simplified and can be more fruitful.)

But what happens if the most powerful critic of human rights in the country is President Duterte himself?

Duterte, on multiple occasions, let loose expletives against human rights investigators, United Nations rapporteurs, activists, even the concept of human rights itself. This messaging and hostility, especially against the CHR, penetrated the mindset of cops.

In the middle of discussions, Taglucop recalled how rookie and senior cops alike would complain why the Commission seemed to protect criminals, among other accusations that do not stray from what’s being said by Duterte’s spirited supporters on social media.

“Dapat kalmado ka lang sa pag-explain mo kasi kung mainit rin ulo mo, hindi magiging maayos ang negotiation and discussion,” she said. “Kailangan talaga ng pasensya…kahit na ganoon ang level ng perception nila sa ’yo at sa trabaho mo.”

(You need to be calm when explaining because if you are hot-headed too, the negotiation and discussion won’t go smoothly. You really need patience even if their level of perception of you and your work is like that.)

The PNP and its duty

Taglucop admits it can be frustrating, but acknowledged that the issue needs to be addressed.

“Iyon ang trabaho namin na maipakita na iyong pag-protect ng human rights, hindi lang siya trabaho ng CHR, trabaho rin ng estado,” she said. “Bilang law enforcers, dapat sila iyong manguha sa pag-protect at respect ng human rights, hindi iyong kayo iyong nang-a-abuso.”

(It’s our job to make them realize that protecting human rights is not only a task given to the CHR, it’s also mostly a responsibility of the state. As law enforcers, they should be at the forefront of protecting and respecting human rights, instead of being the abusers.)

“We can only do this with the help of the people,” Calanoga said, describing their internal cleansing campaign.

The acting HRAO chief lamented that there is a “climate of distrust” between citizens and policemen that they need to remedy to move forward with their mandate.

For the PNP HRAO office, as long as Duterte does not tell them to violate the law, the President cannot be corrected.

During the pandemic alone, the President said quarantine violators who fight back should be shot dead, which is a direct contradiction of the PNP’s rights-based principle of restricting suspects with maximum tolerance.

“I am not in the position to question the wisdom of the President or whatever the things drive him to express those statements,” Calanoga said.

On the ground, human rights policemen are deployed in major police stations. They are required to join anti-drug operations to observe and report any lapses.

There have been no reported abuses raised by these officers to the HRAO office in Camp Crame.

In a phone interview with Rappler, Manila Police Station 2-Tondo Commander Lieutenant Colonel Magno Gallora Jr said their human rights police officers joined operations and reported to him about lapses in the operations, which could mean mishandling of evidence and a misstep in processes.

He said that he lets these erring policemen explain to him first, then he admonishes them for their lapses. He said there have been no lapses that warranted a complaint.

Institutionalizing training?

CHR Commissioner Gana said it would be good if the PNP would institutionalize human rights training, requiring each and every personnel to undergo lectures that only a fraction of the entire police force would otherwise attend. It is an effort to counter the overwhelming false narratives peddled by state-sponsored trolls.

After all, a police force that does not understand the basic concept of human rights – especially the rights of the accused and the importance of due process – poses a grave threat to all Filipinos.

A thorough human rights education as part of the state force’s curriculum, Gana said, would mean a lot for the country.

“Your lens will change since you’re not only after penalizing them,” Gana said. “Magbabago ang perspective mo (Your perspective will change), and you’ll be able to treat the criminal kinder, with more compassion and more understanding.”

Still, the rampant human rights violations committed by state agents will most likely not end with robust training, especially if there is no tough check and balance within the PNP system.

Human Rights Watch’s Asia researcher Carlos Conde said that the PNP HRAO is just being “misused by the government for propaganda purposes,” and not so much for accountability for serious violations in its ranks.

This makes the HRAO only a “token compliance.”

“If the government wants to institutionalize human rights, it must go beyond training,” Conde told Rappler in an email on November 19.

“It has to show that the HRAO is an instrument for accountability and to end impunity.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Rappler’s Best] Patricia Evangelista](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/unnamed-9-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=486px%2C0px%2C1333px%2C1333px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.