SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

For the better part of 2020, Filipinos have been stuck in a spiral of reaction, going back and forth between lockdowns and reopenings that don’t do much to avoid leaving the country trapped in deadly repetition.

The Philippines enters its 17th month of the pandemic – and President Rodrigo Duterte’s final year in office – with the same problems that have plagued its response from the start.

“People aren’t paying attention to what we feel will be very critical to move the response forward and to move it more efficiently,” said Dr. Anna Ong-Lim, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital (UP-PGH) and member of the Department of Health’s (DOH) technical advisory group.

The toll of that short-sightedness has been enormous. Over a million Filipinos have gotten sick, more than 27,000 lives have been lost, and millions more have fallen into financial misery. All the while, recovery remains fragile.

Since the pandemic broke out last year, the Philippines saw two surges – in July 2020 and April 2021 – both of which have plateaued, but not truly subsided. Now, a third, potentially deadlier surge threatens the country as the coronavirus Delta variant sweeps through Southeast Asia.

The pandemic is not impossible to control and there are ways to do so beyond lockdowns and vaccines, as Duterte has often suggested. Yet, the President continues to fall into helpless thinking. “We will just have to pray for salvation,” Duterte said in his final State of the Nation Address on Monday, July 26.

This lack of political will to pull Filipinos out of a crisis is harmful, said Dr. Antonio Dans, an internal medicine specialist and epidemiologist at PGH. Until now, the emphasis has been on the public’s compliance with minimum health measures, but experts Rappler interviewed believe that the government and legislators can take certain actions to break the current spiral.

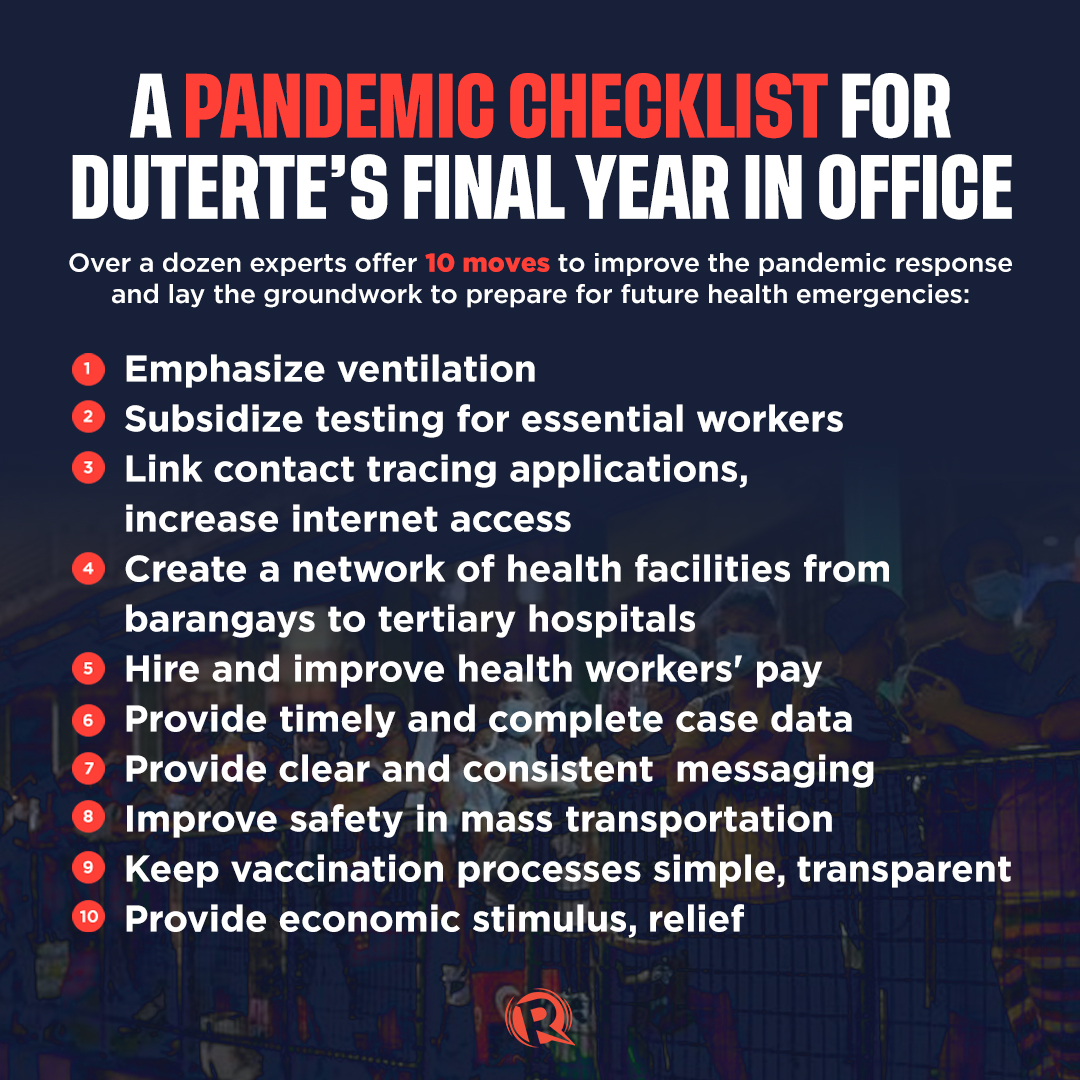

Here are 10 actionable steps Duterte and his Cabinet can take in their final year. These initiatives proposed by over a dozen experts can help the local epidemic and prepare the Philippines for future health emergencies.

1. Emphasize ventilation

Sorely missing from public messaging on health and safety measures is ventilation. “In as much as vaccines are going to be recognized as a game changer, I think we have to sell the idea that ventilation is also going to be a major game changer in terms of transmission,” Ong-Lim said.

It’s been difficult to shift thinking here because it took over a year for governments and the World Health Organization (WHO) to establish that the coronavirus can be airborne. Even then, policies have yet to catch up.

“We need the powerful to really understand how the virus works, how it spreads. I don’t think that actions reflect that kind of insight,” said Dr. Lei Camiling-Alfonso, a technical specialist for the Philippine Society of Public Health Physicians.

While the coronavirus spreads mostly through the air, visit any public space and you’ll find most establishments still paying more attention to scrubbing surfaces and checking people’s temperatures rather than ensuring good airflow. Such moves are not entirely useless, experts said, but they can’t replace more effective measures.

If officials truly understood that COVID-19 spreads in poorly-ventilated and crowded spaces, then open spaces would be made more accessible than riskier indoor ones. Streets could be pedestrianized for businesses, while parks and beaches can be promoted as alternatives to malls.

“We keep opening to the same thing that we closed down to…. That’s part of how we’re killing the economy,” Dans said.

If we’re to truly “live with the virus” then government and business owners need to learn how to read carbon dioxide levels and ensure places are well ventilated. Other countries have shown that making adjustments won’t always require building new infrastructure but redesigning existing ones to become safer.

“It is not as difficult as it seems. At times, it can be as simple as getting an electric fan and opening the windows,” Camiling-Alfonso said.

2. Subsidize testing for essential workers

Although testing capacity has increased considerably (with at least 300,000 samples now tested weekly), fees remain too high for health workers and essential workers, especially minimum wage earners.

A possible way through is for government to subsidize tests for frontline workers who don’t have the option of working from home.

Some local governments and national agencies have provided free COVID-19 tests to a certain extent, but most Filipinos still pay for their own tests. Prices range from at least P1,750 to an average of P3,000 to P5,000, or as much as P8,000 in private facilities.

The Philippine Health Insurance Corporation offers some coverage, but it does not apply to all testing centers. Cumbersome paperwork can also cause delays, while slow reimbursements from the government can hamper lab operations.

“Government has done 80% of the homework for testing. There’s still that 20%,” said Jason Haw, an epidemiologist.

Makati Business Club chairman Ed Chua supports subsidized testing of essential workers. Without making sure that working Filipinos at greater risk of contracting COVID-19 could get tested, increased testing capacity only serves as “bragging rights,” he said.

Testing can also help identify areas where vaccination and other measures are needed more. “Where might you need to shift vaccines? Where do you put more contact tracers? Where do you build more isolation facilities? We still need to do testing (to help determine that),” said Albert Domingo, a health systems specialist involved with the WHO.

3. Link contact tracing applications, increase internet access

Experts whom Rappler spoke with were unanimous in calling for improvements in contact tracing. Lacking manpower and being stuck with pen and paper, the Philippines has yet to meet the ideal ratio of 37 contacts located per each COVID-positive individual. The use of current digital applications like Stay Safe has likewise been fragmented.

On the ground, it can take five days, sometimes even weeks, to locate and isolate people who may have been exposed to an infected person. This puts the virus perpetually a step ahead of contact tracers.

Some cities, including Pasig, Mandaluyong, and Valenzuela have shown a way forward by linking their digital contact tracing systems. In Pasig City, data from testing labs have also been connected to the city’s PasigPass system for quicker notification of contacts.

Connecting tracing applications to testing laboratory databases and the DOH’s COVID document repository system is also crucial, said Dr. Aileen Espina, a family medicine and local health systems development specialist.

But to even get to that, Espina reiterated the call of the Health Care Professionals Alliance Against COVID-19 (HPAAC) to improve internet access. A World Bank report published in October 2020 found that the digital divide in the country remains large, with nearly 60% of households having poor or no access to the internet.

“People don’t see this being directly related to a health response and yet it is actually the backbone of the entire pandemic response,” Ong-Lim said.

Philippine Alliance of Patient Organizations board member Karen Villanueva echoed the push, saying it could aid in the treatment of patients who have difficulty accessing care during the pandemic for COVID-19 and other health concerns.

But beyond health, better internet access can also mean giving students badly affected by school closures a shot at continuing their education. Improvements can save businesses from shutting down.

DHL Express Philippines country manager Nurhayati Abdullah said this was the case in neighboring countries, too. “What is really evident is that everyone is trying to get contactless interaction, so this drives technology and automation to be more crucial.”

Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea have proven that investments in information and communications technology can help control COVID-19. Even an SMS-based alert system for contact tracing would be beneficial, Haw said, pointing to Taiwan’s example.

4. Create a network of health facilities from barangays to tertiary hospitals

It’s been a constant ask from the medical community since the country faced its first surge, but over a year later, this has only been partly fulfilled.

After hundreds, if not thousands, of Filipinos were left with no choice but to survive COVID-19 at home or on emergency department waiting lists, the DOH announced it created a “triage system” to manage the flow of patients needing care across local government units. But since April 2021, the process of setting this up has been slow.

In the meantime, emergency medicine specialists have called for the inclusion of ER statistics public dashboards. They said it could better reflect three things that signal the health system’s state: patient demand, available space in other parts of the hospital needed for admission, and efficiency of referral systems among different facilities. So far, it remains on their wish-list.

Meanwhile, officials have turned to adding beds and building more isolation facilities as a quick, but limited fix.

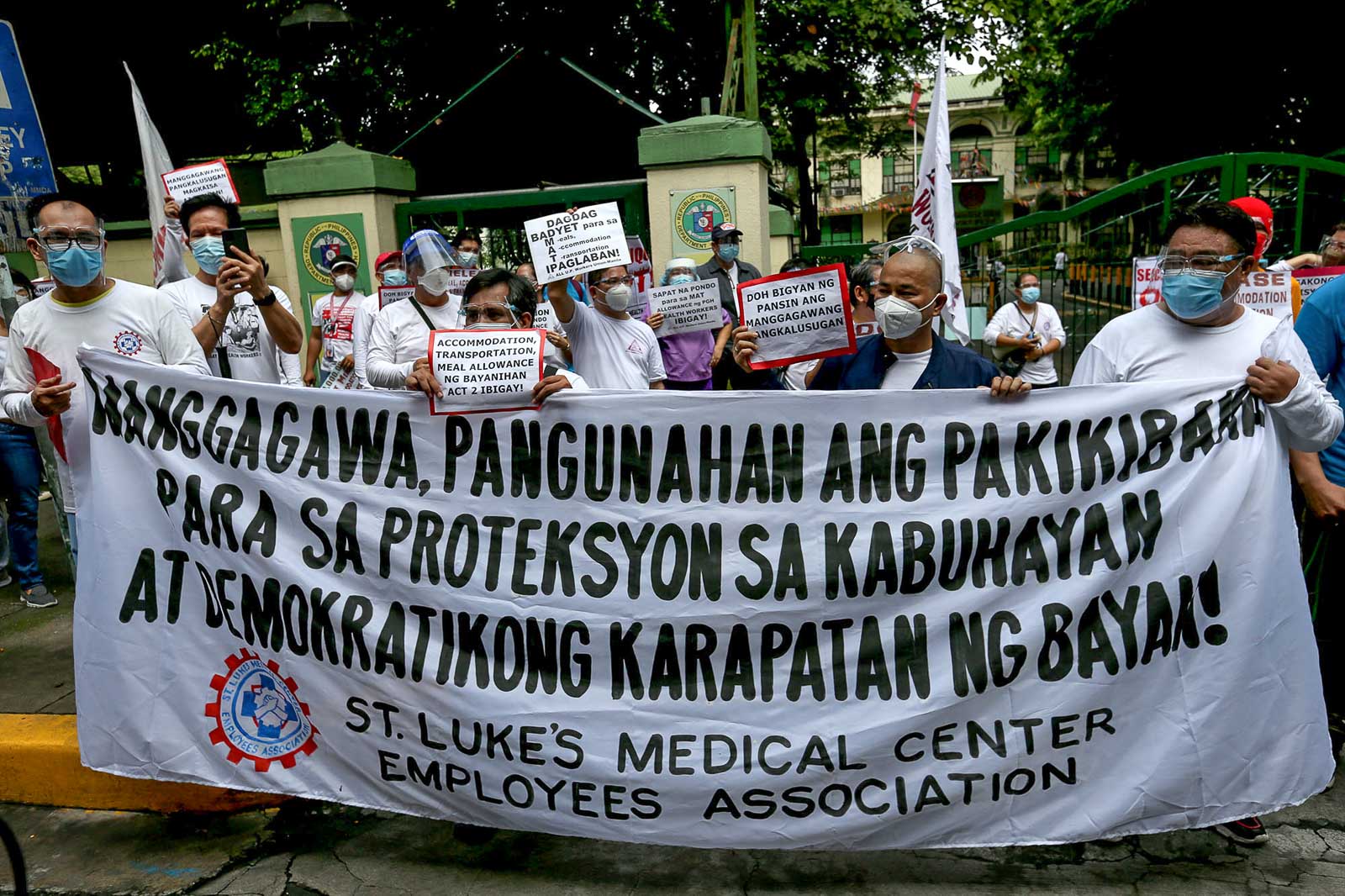

5. Hire and improve health workers’ pay

An even more scarce resource in the Philippines’ health system is the number of workers needed to treat patients. The pandemic has emphasized the need to take care of health workers, yet they remain deprived of better working conditions, pushing thousands to work abroad.

“Healthcare workers are referred to as heroes here and in many countries, [but here]…they’re being treated like slaves,” Dans said. Filipino nurses have fought decades for better pay, even winning a Supreme Court ruling against the government, but without proper funding, many continue to wait for what is due them.

Promised pandemic benefits like hazard pay and special allowances are likewise delayed at best. “They should increase our pay to minimum wage, at least, not give us a ‘libing (funeral) wage,’” said Alliance of Health Workers president Ronald Mendoza.

Beyond hospitals, Haw said more workers could be hired to staff local epidemiology surveillance units year-round. “It’s something you can scale up and use to create a pathway for more people to stay in local government, where they can respond to not just a pandemic, but any kind of infectious disease,” he said.

6. Provide timely and complete case data

Independent scientists and researchers have repeatedly called out the government’s weaknesses in data management, saying discrepancies in national and local numbers create confusion among the public.

Mathematics professor Jomar Rabajante of the UP Pandemic Response Team said part of the problem is that information is all over the place. He suggested government integrate all databases from the DOH’s Epidemiology Bureau, local government units, and hospitals into one system to speed up validation and address data inaccuracies.

Public administration and disaster risk governance specialist Kristoffer Berse of UP said the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) could lead the effort. With an improved grasp of data on the virus and its spread, a general understanding of the health crisis in the country would be greatly improved not only among the public, but also among government agencies who need it for decision-making.

Bill Luz, chief resilience officer and advisor at the Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation, said better data would, in turn, allow more experts and independent researchers to contribute solutions.

7. Provide clear and consistent messaging

Quarantine restrictions are entirely different compared to a year ago because the government has constantly adjusted what can and can’t be done. Is it any wonder most Filipinos have lost track of how to adjust to an enhanced, modified, or general community quarantine – with or without “heightened restrictions”?

Experts pointed out this was emblematic of another big weakness in the government’s response: incoherent pandemic communication.

The mixed messaging, Octa Research fellow and microbiologist Fr. Niacanor Austriaco said, points to the lack of foresight and stable sources of data to guide the government’s response. “That kind of lack of a solid foundation, that is open to politics. It has become who has the loudest voice and that will sway the policy.”

With decisions hinged on personalities rather than clear evidence, much of the messaging on pandemic measures has been conflicting not only in officials’ words, but in their actions, too.

While Duterte officials continue to assert their adherence to “science” in decision-making, the reality is, many politicians have tried to dictate scientific and medical review processes. Government itself is likewise often the first to violate its own rules. The last few months were rife with pandemic violations from those in power, most of whom were never held accountable.

“The message that the government seems to send is that everybody do as we say, not as we do,” said Communication associate professor Inez Ponce de Leon of the Ateneo de Manila University.

8. Improve safety in mass transportation

If the virus spreads with increased mobility, then safety in transportation needs more attention. Toward safer mass transport, HPAAC and mobility experts proposed a “first mile and last mile approach” that integrated public and active transport.

Under the strategy, Filipinos can bike to bus or train stations, ride to their intended stops, and bike once again to reach their destinations. Measures like allowing bikes on trains, providing bikes for rent, and pedestrianizing more streets could aid this effort. Even putting up more bike lines and installing bike racks in terminals could make mass transport safer.

Calls have also been made to continue the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board’s (LTFRB) service contracting system, which tapped public utility vehicles to give free rides to the public. The program was paused after Bayanihan 2 expired on June 30, but the LTFRB said it would use its 2021 budget to continue the service. Almost a month later, the program has yet to resume.

9. Keep vaccination processes simple, transparent

The remaining months of Duterte’s term will revolve around hitting targets, which requires upping the number of doses given daily.

In the immediate term, long lines outside sites need to be addressed, especially when this is in enclosed spaces, HPAAC said. Experts said the safety of vaccines must be emphasized in public messaging, besides the dangers of COVID-19. Employers, meanwhile, can encourage vaccinations by providing paid sick leaves that allow employees to get their shots without the risk of losing income.

Dr. Tony Leachon, a health reform advocate and former government adviser, said public trust in the vaccine drive can be increased if the vaccination process were more transparent and open to “independent advice and guidance” from academe, consumer advocates, and the medical community.

Luz said the private sector continues to coordinate with government officials on the vaccination front. In daily meetings, he said, performance is evaluated with the use of a “scenario model” or calculator that maps out how many doses per hour, vaccine centers, manpower, appointments, and other supplies will be needed for local governments to reach at least 70% of their populations.

The calculation is being shared with local officials as a guide that could be tweaked and is being used to plan for the next six months, at least.

10. Provide economic stimulus, relief

Finally, to ride through more months of uncertainty, economist JC Punongbayan said financial aid must be given to sectors most affected by the pandemic – the poor, workers, and small business.

That means channeling funds to programs that actually tackle urgent actions needed to solve problems posed by a new virus and lockdowns, including cash transfers to the poor, unemployment assistance, aid for farmers and fisherfolk, as well as allowances for health workers, students, and teachers.

But ensuring money goes to the right places will be made more challenging, especially in an election year when “aid will be politicized for sure. But the trick is to ensure that aid keeps flowing well after the elections. Our economy’s survival hinges on it,” Punongbayan wrote in a Rappler analysis.

Chua pointed out that “there is space for us to provide that support to spur consumer consumption.” The Philippines has had one of the weakest fiscal responses to the crisis in Southeast Asia – despite being among those most badly affected.

That task of prioritizing programs falls not only on the executive branch but on Congress, too. “Is the budget for intelligence job-generating? The budget for anti-communism job-generating? We need to spend money where it is required – health, education, agriculture, public works,” he said.

The imperative for providing aid is high, with a recent Pulse Asia survey showing nearly 1 in 5 Filipinos identified it as the primary weakness of government’s response to the pandemic.

Risk of forgetting

Failing to take measures to shepherd the country out of the pandemic leaves Filipinos not only vulnerable to this present crisis, but those in the future. “It’s a very critical point in time where if there’s anything that can be done, it has to be done now before the surge happens,” Ong-Lim said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Ang low-intensity warfare ni Marcos kung saan attack dog na ang First Lady](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-liza-marcos-sara-duterte-feud-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=294px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newsstand] Duterte vs Marcos: A rift impossible to bridge, a wound impossible to heal](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/duterte-marcos-rift-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=278px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.