SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Not even the tough-talking Rodrigo Duterte, the first president from the Philippines’ restive south, dared to mention the “S” word in his meeting with then-Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad in 2018.

It is the name never to be spoken – Sabah – if the Philippines wants smooth ties with its good neighbor Malaysia. Known for its oil palm plantations and scuba diving spots, Sabah is the resource-rich land occupied by Malaysia but claimed by the Philippines as part of its southern islands called Mindanao.

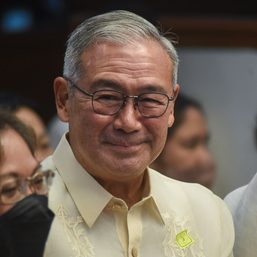

It took a tweet by Philippine Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr – a man who, also on Twitter, agitated even Singapore’s top diplomat Vivian Balakrishnan – to revive a controversy that many career diplomats have chosen to keep dormant.

On July 27, Locsin berated the US embassy for tweeting that America donated hygiene kits to Filipinos from “Sabah, Malaysia.” “Sabah is not in Malaysia if you want to have anything to do with the Philippines,” Locsin tweeted the US embassy, which refused to take down the tweet.

Two days later, Malaysia on July 29 said it will summon the Philippines’ ambassador to Kuala Lumpur, Charles Jose, over Locsin’s “irresponsible statement.” Locsin shot back by summoning Malaysia’s ambassador to Manila.

Is this the right time to reassert the Philippines’ dormant claim to Sabah? How should the Philippines and Malaysia move forward?

How it all began

The Philippines’ claim over Sabah stems from a basic question: Did the Sultan of Sulu through a document signed on January 22, 1878, sell or merely lease Sabah to the British, who ruled the area now known as Malaysia?

Malaysia interprets the 1878 document to mean the Sultan of Sulu, Jamalul Alam, sold Sabah to the British. The Philippines asserts the Sultan merely leased it.

The catch is, for decades, Malaysia paid the heirs of the Sulu sultanate RM5,300 or around $1,200, based on the 1878 agreement. For the Philippines, that Malaysia is paying rent means Sabah was only leased to the British. Malaysia, on the other hand, considers the RM5,300 as payment for the cession of Sabah.

Malaysian Foreign Minister Hishammuddin recently said, however, that Malaysia stopped paying the Sulu sultanate’s heirs since 2013.

“The whole controversy is whether he leased it or sold it to a company called the British North Borneo Company,” said historian Manuel L. Quezon III said in an ABS-CBN interview in 2013.

The Philippines has not dropped its claim over Sabah, even as many presidents have kept it dormant. Still, it has occasionally erupted into huge crises that have served as turning points in history.

One of these is the Jabidah Massacre. On March 18, 1968, a foiled Marcos plot to retake Sabah led troops to shoot dead at least 23 military trainees on Corregidor Island. The Jabidah Massacre – which sparked the 4-decade Muslim rebellion in Mindanao – damaged ties between the Philippines and Malaysia, to the point that the two countries halted diplomatic relations in September 1968. (After high-level talks, the two countries resumed diplomacy in December 1969, even as Sabah remained a thorn in the side.)

The late ambassador Rodolfo Severino, in his book Where in the World is the Philippines?, said that while the Sabah dispute “has long receded into irrelevance,” Philippine leaders “have found it politically impossible to drop the Philippine claim to Sabah altogether.”

Dictator Ferdinand Marcos tried to drop this claim in August 1977. In a regional summit, Marcos declared that the Philippines is “taking definite steps to eliminate one of the burdens of ASEAN – the claim of the Philippine Republic to Sabah.”

Severino, however, wrote: “As it turned out, neither Marcos nor any of his successors managed to take those ‘definite steps’ to abandon the claim to Sabah, at least not in terms acceptable to Malaysia. The political pressures to do so were just not enough; the pressures not to do so were too great.”

Decades after the Jabidah Massacre, the Sabah controversy flared up again when followers of self-proclaimed Sulu sultan Jamalul Kiram III engaged in a standoff with Malaysian troops over a village in Sabah. Then-Philippine president Benigno Aquino III condemned the gunmen’s Sabah incursion and – save for times when politicians used Sabah in politicking, as then-vice president Jejomar Binay did – the Philippines’ Sabah claim has relatively been silent since then.

One issue that persists, however, is how the Philippines can attend to at least 800,000 Filipinos living in Sabah. Proposals have been floated to establish a Philippine consulate in Sabah, but this would mean conceding that Sabah is indeed a foreign land. The workaround, for now, is for the Philippine embassy in Kuala Lumpur to dispatch teams to attend to Filipinos in Sabah, toiling without sabre-rattling or mindless tweets.

Virtue in silence

Even Duterte knows there is virtue in silence about Sabah. In his first meeting with Mahathir in July 2018, the thorny topic wasn’t even on the leaders’ agenda, despite Duterte vowing to pursue the claim as a campaign promise.

Not even when Malaysia was angered over a proposal to make Sabah the Philippines’ 13th federal state under a revised constitution would Duterte speak up.

The Philippine government kept its cool even when Mahathir – asked in a television interview about his comments on the Philippines’ Sabah claim – boldly shot back, “There is no claim.” It was left to then-presidential spokesperson Salvador Panelo to counter it has been “the bone of contention ever since.”

But even if Duterte were to bring up Sabah, analyst David Han of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore said there is little the Philippine president could do to change the status quo.

In an RSIS commentary in 2016, Han said Malaysia would strongly safeguard its claims as the area has rich maritime oil reserves and was a factor in electoral success. Sabah’s entry into Malaysia in 1963 was also legally recognized by the United Nations.

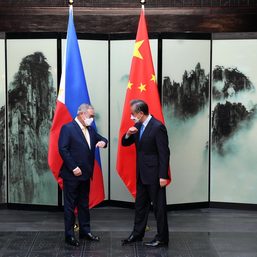

Beyond the Sabah claim, the Philippines and Malaysia have likewise worked together to prevent the spread of terrorism in the region while Malaysia also played a crucial role in mediating peace talks between the Philippine government and former Muslim rebels in Mindanao.

Divisive distraction

In trading tweets over a dormant claim, University of the Philippines (UP) Political Science Chair Herman Kraft said the Philippines and Malaysia invite distraction at a time when countries require focus to address complex problems.

Southeast Asia, home to a diverse set of nations, already battles a pandemic that requires close collaboration as a new wave of infections surge in the region.

It is important to keep the region united, Kraft added, in the face of the power play between the United States and China.

“Best case scenario is that it will be resolved through diplomacy, most likely involving Indonesia. Worst case scenario is that this will escalate into a diplomatic crisis which ASEAN may find difficulty recovering from,” Kraft told Rappler.

Kraft said ASEAN member-states cannot afford division as China continues its aggressive behavior in the South China Sea. Kraft pointed out that without a united ASEAN that can balance the two powers, tensions between the US and China in the region may likewise be inflamed.

While Locsin’s Twitter remarks prompted Malaysia to summon the Philippine ambassador, Kraft said the statement being limited to social media, as opposed to an official statement, provides the opportunity to reel it back in.

“It has the possibility of straining ties but realistically, unless thoughtless action follows loose lips, the Philippines and Malaysia should be able to settle this,” Kraft added.

Julkipli Wadi, professor and former dean of the UP Institute of Islamic Studies, said in an email to Rappler: “It’s interesting to know whether Secretary Locsin raises the Sabah issue through Twitter simply as a knee-jerk reaction to US embassy’s seemingly innocent or callous identification of Sabah with Malaysia; or, if he has a bigger plan. What is the plan, if any?”

“The lesson to learn on Philippine government’s handling of Sabah issue these past several years may be summarized into this: Apart from lack of wherewithal and reversals of commitment on Sabah claim, the Philippines has been successively outmaneuvered by Malaysia in both legal and geopolitical contests, as Kuala Lumpur knows pretty well its nemesis’ propensity to play with words than deeds,” said Wadi.

Pragmatic option

Malcolm Cook, a Southeast Asia analyst with the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said Locsin’s tweet “could have been better worded,” as “not commenting on it could have left Foreign Secretary Locsin open to criticism from Philippine nationalists who focus on the Sabah claim.”

While it is very unlikely any Philippine government will drop the claim to Sabah, keeping quiet about it when possible is pragmatic.

Malcolm Cook, Southeast Asia analyst

The best way moving forward, he said, is for Manila in the short run to “stop the current tit-for-tat with Kuala Lumpur as the point has been made.” In the longer run, he said, Manila can “offer to take the dispute to the International Court of Justice” – although Malaysia needs to give its consent for any case to proceed.

Cook, however, said he cannot foresee a scenario in which the Philippines can gain control of Sabah, as the Philippines’ claim “is very likely to remain a claim with little support outside of the Philippines.”

Cook said, “Given the location of Sabah, and Malaysia’s control of Sabah, the Philippine government is the one who has to bring up the dispute and is seen outside the Philippines as the problem-causer. While it is very unlikely any Philippine government will drop the claim to Sabah, keeping quiet about it when possible is pragmatic.”

Time will come, many Filipinos hope, when the Philippines can fight tooth and nail to call Sabah its own. But this requires more than bravado online.

For now, reality bites: Malaysia is one of the 5 countries with the most Filipinos overseas, a leading source of tourists, a partner in fighting piracy and terrorism. It is an ally through the years despite the often unspeakable “S” word.

And it was an 80-character tweet, of all things, that got the Philippines in trouble. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.