SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In the corner of a room tucked away in the Nara prefecture in Japan, Filipino worker Camile Ferrer clutches her cell phone and presses its screen as close to her face as she could.

“Show me your teeth,” Camile says. Beyond the screen, her 8-year-old daughter Lara opens her mouth wide. Upon examining each tooth, Camile finds stains and warns Lara, “Brush your teeth every time you eat! Okay?”

Since leaving to work in Japan, video calling through Facebook Messenger is the only way Camile stays connected to her home in the Philippines, an ocean and thousands of kilometers away from her room.

Out in Barangay Pulong Norte, Malasiqui, Pangasinan, in Central Luzon, Camile’s daughter and her 5-year-old son Angelo live with her mother Lanie, 56, where they wait for Camile to visit home soon, if only the coronavirus pandemic would let her.

Almost every day, either early in the morning or at night, Camile calls her children for one or two hours. As a single mother, she considers this as her precious time for “parenting.”

As she checks if Lara brushes her teeth regularly, Lara also tells her mom that Angelo did not pay attention to their teacher during class that day. Camile warns her son and tells him to study hard for school.

Often, Lara and Angelo ask their mom for toys when they call. Camile said their top requests were “surprise eggs” and items of Despicable Me minions. Camile often sends money to her mother to buy these, if her children study hard and get good grades.

“This is my advantage when I came to Japan. When I was in the Philippines, I could not provide them what they wanted,” Camile said. “And that is my happiness too, giving them what they want.”

Coping with separation

But the sacrifice of providing for her children, Camile admits, is never truly easy to accept. While she worked to send her kids to school and made sure they had enough funds in case any of them got sick, Camile must support her family alone.

For 5 years, Camile worked as a supervisor and moonlighted as a nurse at the SM Hypermarket in Mall of Asia and would earn P25,000 a month – not enough for a single mother to cover her family’s basic needs.

Having heard of Japan, its picturesque landscapes, as well as how people were polite and kind, Camile decided to search the internet for job opportunities. She stopped only when she found an economic partnership agreement (EPA) that Japan had signed with the Philippines in 2006. She saw it would allow her to work abroad as a caregiver.

After finding a Japanese company that would pay for her language school and support her training as a nurse for the elderly, she set her mind on leaving home. But while the EPA program would allow Camile to make a living in Japan, she would not be allowed to bring her family with her.

Until this day, the memory of Camile’s last moments in the Philippines still linger in the mind of her family. Her mother Lanie recalled Angelo crying non-stop when Camile said goodbye to her family at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport.

“I wish mama was here,” Lanie recalls Angelo, only 3 years old at the time, saying over and over. “I remember when we left the airport, he could not stop crying,” she recalled.

Camile said seeing her son in tears left her anxious to leave. “But I have to be strong. For me. And to get them to Japan in the future,” she added.

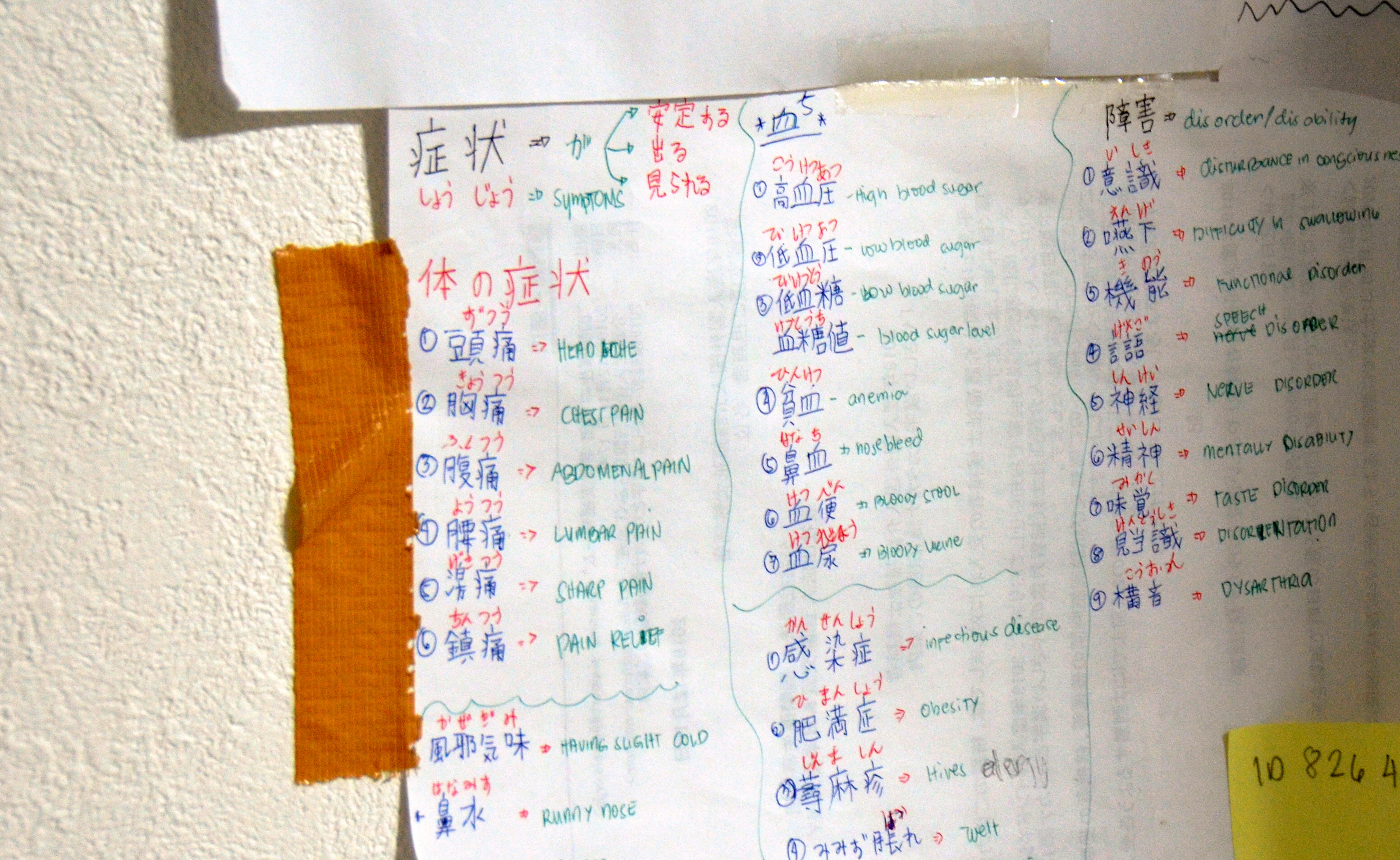

This has been Camile’s dream. Keeping it in mind, she has found ways to adjust to life in Japan. She is proud she has learned how to read Kanji, decipher signs in train stations, and muster the courage to talk to Japanese all by herself.

Pandemic strikes

But when the pandemic took over in March 2020, being away from home became even more difficult.

Camile initially found herself worried for her family in the Philippines. While she had started to grow used to the distance, the anxiety of one of her children getting sick or being unable to attend school introduced another level of stress she needed to cope with.

As a mother, Lanie worried for her daughter, too. “I pray that my family will be safe from any disasters and disease, especially since my daughter is a medical worker. I pray that God may protect them always with His mighty love. This is always the prayer of a mother for her child,” Lanie shared.

Lanie said she thought of asking Camile to stop working for a while and to come back home. But she never got the chance to tell Camile what she was thinking because whenever they would talk on the phone, her daughter would reassure her she was safe.

This was enough for Lanie, who understood why her daughter chose to keep working despite the risk of getting infected with COVID-19.

For Camile, it was all the more important to keep her job as the pandemic made it necessary to keep earning to make sure her children stayed in school. Apart from that, Camile needed to ensure there was money in case of any emergency, too.

Excluded from assistance

Unlike other indigent families, Lanie and her family did not receive the Duterte government’s emergency subsidy during the first months of the lockdown in March 2020.

As barangay captain, Lanie said the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) told local officials that having a member working overseas made families ineligible to receive cash assistance since it was assumed they were still receiving support through remittances.

But Lanie said having a family member working overseas should not automatically mean they no longer need assistance. “It (exclusion from aid) is not that accurate because each person is different. A child or parent can be abroad, but they’re also on lockdown there (in other countries).”

Lanie said this was common for many households in their barangay, who needed assistance but were unable to gain access because they had a family working overseas. This angered many in their community, she added.

“We asked for help from the DSWD, so that they themselves can determine who will get the assistance and we won’t be blamed,” Lanie said.

A working paper from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (Unicef) has pointed out that this gap in access is common among countries’ social welfare programs and often disadvantages children left behind by parents working as migrant workers.

Especially during emergency situations, such welfare programs often fail to take into consideration the uncertainty of remittances that families of overseas Filipino workers (OFW) rely on.

“Children ‘left behind’ are often excluded from social service programs because they receive remittances and are seldom classified as living in poverty….If monthly income is high, it can mean children lose access to programs for a period of time – and this makes families who receive sporadic remittances even more vulnerable,” Unicef said.

Yasmin Ortiga, a sociology professor at the Singapore Management University pointed out, “There must be a more nuanced, or more specific way to determine whether a family needs aid or not beyond just the OFW family member…. The problem in an emergency is, people need to disburse funds very quickly.” Ortiga specializes in research on international migration and inequality.

The pandemic, according to Ortiga, has also made it more evident that having a family member working abroad should still allow that family to have access to government programs.

Ortiga said that in the same way the pandemic has exacerbated weaknesses in social welfare programs, the health crisis and its impact on migrant workers “reminds us that the stereotype of the migrant worker has been used to proxy everything from troubled children to access to aid, to a kind of explanation of what these families are going through.”

“We always know that it’s, it’s much more varied than that,” she added.

While families of OFWs are not eligible to receive aid from the DSWD, Lanie said her family has not been able to avail of aid from the Department of Labor and Employment or Overseas Workers Welfare Association either, as these were mostly limited to returning workers unable to leave the Philippines and find work due to the global health crisis.

She has since stopped looking for help from the government.

Limits abroad

Unable to look forward to a date when she can return to the Philippines, Camile said the growing number of months and days since she last saw her kids has made her even more determined to work hard so she could bring them to Japan.

“I have endured and endured, but I didn’t expect the pandemic to go on for such a long time. Nowadays, I feel tired a little. I want to see my kids,” Camile said.

More than having her family visit, Camile said she continues to work hard in the hope of bringing her family to live with her in Japan in the future.

Among migrant workers, those with “technical intern trainee visas” make for the biggest category, with about 400,000 workers issued such visas. But under this visa category, workers are not allowed to bring their family members to Japan.

Japan’s specified skilled worker visa, which was introduced in 2019 to address labor shortages in 14 industries, also mostly bans workers from bringing family members along, resulting in separations.

Meanwhile, like technical intern trainees, caregivers under the EPA between Japan and the Philippines are prohibited from bringing their families, too, when they work in Japan.

During deliberations on the introduction of specified skilled worker visa in Japan’s Congress, known as the Diet, opposition lawmakers criticized such bans as “a serious violation of a right,” and called for workers to be given permission to keep their families intact.

However, then-prime minister Shinzo Abe warned that “if Japan accepts their family members, we need to consider the support for them,” adding that it was necessary for government to reach consensus from “wider perspectives” or majority.

Economic and social costs

Chiho Ogaya, a sociologist studying labor migration at Japan’s Ferris University, stressed that such thinking was harmful to workers’ families. Ogaya also specializes in Filipino migrant workers and their families,

“It is the basic right for families not to be separated. The government policies which do not acknowledge the right is problematic,” Ogaya said. She added that such measures preventing some types of migrant workers from brining their families likewise iIllustrate how governments want to gain from the labor force, but avoid the burden of economic and social costs coming from migrants’ families.

But Ogaya noted that in doing so, countries receiving migrant workers – like Japan – may also miss out on maximizing the potential of workers to contribute to their society.

This much is true for Japan’s aging society, which has prompted its government to look for more foreign workers in anticipation of a labor shortage in the coming years.

“Migrant children raised in Japan have great potential and an important role to encourage diversity in Japanese society as they are multilingual and have a multicultural background,” Ogaya said.

“If Japan is thinking of the long-term, they should accept migrants’ children,” she added.

Challenges ahead

For workers like Camile, there is a glimmer of hope.

Under the EPA program between the Philippines and Japan, if migrant caregivers pass a national exam to become a certified care worker in Japan within four years, they can gain resident status that will allow them to stay in the country and bring their families to live with them.

“Sometimes I think I want to go back to the Philippines. But I have decided to work in Japan for the future of my children. My dream is living with them and providing them with good education,” Camile said.

Still, this is uncertain at best. While the EPA program offers the option for workers like Camile to gain permanent employment, if they fail to pass qualification exams to become certified caregivers, they must return to their home countries.

If workers fail to obtain qualifications within the prescribed 4-year time frame, workers will also need to leave Japan.

Camile now has two years left to study and pass Japan’s qualification exam for caregivers. But the pandemic has made it harder to attain this dream.

After some of Camile’s co-workers resigned, her workload got heavier, and studying for her certification exam, more taxing.

“Nowadays, it’s getting difficult to study. Sometimes I’m so tired and I cannot memorize what my teacher says because my work is getting hard,” Camile said.

Experts studying the impact of the pandemic on migrant workers and their families have said that with governments focused both on the repatriation of their workers and their response to the health crisis, the well-being of overseas workers who remain overseas may often go unnoticed.

This leaves workers like Camile to rely mostly on themselves when coping with work and making ends meet. Like in the Philippines, the Japanese government has given little assistance to foreign workers in the country, many of whom were also the first to be laid off when the pandemic hit businesses.

Aside from this, Carmel Abao, a political scientist professor and migration expert at the Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines, pointed out that the Philippine government has yet to adjust labor policies to account for risks and changes in work, which the pandemic has brought about.

If governments in both host countries like Japan and home countries like the Philippines fail to anticipate and prepare for the next emergency or global crisis, this can leave OFWs and other migrant workers vulnerable again, she warned.

Always, for family

On days she’s most exhausted, Camile only has to call and hear the sound of her children’s voices. “Even when I’m just on my bed, I call them just to hear their voice, even if I’m not talking. When they talk, I’m happy,” she said.

At home, Lanie has made sure that even if Lara and Angelo grow sad and ask when they would see Camile again, her grandchildren know their mother is working for their future.

“Sometimes when I have nothing to do, I always think of my mama,” Lara said. “I think to myself, ‘I wish mama was here. I wish that the coronavirus would end so mom can go home. I really miss her.’”

Lara continued: “But Lola and mama said I shouldn’t worry because what she’s (Camile) doing is for us.”

Camile says this to herself too, and will keep reminding herself of it until she gets to be with her children again.

“If I stay here, I can take care of my children in the future – I’m always thinking about that, so I always endure,” Camile said.

She added, “Maybe it’s difficult, but we have to try to live together. At first, money for that will be a problem, and I still have to pass the national exam for caregivers. But after that, my plan can start. In God’s will, I always pray for it.” – with research by Razel Suansing/Rappler.com

*All quotes have been translated to English.

This story, a collaboration between Rappler and Japan’s Asahi Shimbun, was published with support from the Sasakawa Peace Foundation.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newspoint] The lucky one](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/lucky-one-april-18-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=536px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.