SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The Philippine military has a social media problem.

In the past few weeks, its soldiers and units have been entangled in various controversies involving their use of the popular platform Facebook.

At least 3 Army servicemen were identified as being behind a suspended network of accounts and pages displaying “inauthentic behavior” that amplified political messages in support of the Duterte administration.

Meanwhile, various military units have been flagged by Leftist lawmakers as illegally using their social media platforms to red-tag students and activists without sufficient basis.

Department of National Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana defended the posts, including the fabricated ones. The criticism led to the deferment of the Department of National Defense’s 2021 budget deliberations.

The military then found itself at odds with Facebook, demanding that the social media giant explain its takedown of several social media accounts, including the Facebook page of a non-military group that advocated against communists supposedly recruiting the youth into their movement.

President Duterte wanted to take it further. He threatened to ban the platform – the same platform that his campaign effectively used to propel him to Malacañang.

This was not always the case for the military and online platforms.

Social media was not an open battleground where various military pages directly attacked activists.

“Back then, we would use Facebook to look for terrorists and suspects,” said retired general Cesar Garcia, a former national security adviser and former chief of the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency in a phone interview with Rappler on Wednesday, October 14.

According to Colonel Harold Cabunoc, a former Army spokesman who manages a personal Facebook page with over 240,000 followers, social media has become a new battlefield for information between the military and its perceived enemies.

He said they are only amplifying the message of their bosses, who have been adamant about taking down the communist insurgency.

“We wouldn’t use force against the unarmed component of the insurgency. Our only way to fight is through information. And this is where we get bashed,” he told Rappler in a video call interview on Wednesday, October 14.

For Lieutenant General Antonio Parlade – the military’s Southern Luzon Command chief and one of the most controversial military officials owing to his impassioned and often baseless tirades on social media – it’s a matter of winning a propaganda war.

“If before we restrict our soldiers from engaging much in social media, now it is encouraged. The AFP has to win this propaganda fight being waged by the CPP and they are miles ahead,” Parlade said in a text message to Rappler on Thursday, October 15.

Is it all fair game in the war of information on social media?

We trace the beginnings of the military’s use of social media for its operations, examine its present policies, and look at its most controversial users who have triggered critics into slamming the uniformed service for its alleged lack of professionalism and propriety in the platforms.

The discovery of a weapon

The Philippine military formally acknowledged the power of social media in July 2014 when it held its first-ever social media summit inside their national headquarters, Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City.

Around 1,000 soldiers were required and invited to attend the forum, which was held for an entire day and consisted of talks accompanied by slideshows prepared by social media and marketing experts. The military also invited former interior secretary Rafael Alunan, who issued a call to exploit the potential of the platforms to do good.

“They (soldiers) should maximize it in terms of morale welfare, informing their public about deaths, news reports, and weather reports. They can even use it for philanthropic causes, educating internal audiences like their sons and daughters, employment opportunities,” he said.

The event also saw the launch of a 45-page social media handbook for the Philippine Army. The book opens with a preface by then-Army commanding general Noel Coballes, who said that the handbook “will not only tell us what to do but will also remind us of our unwavering responsibility as soldiers.”

The handbook highlighted the potential of social media for the military’s thrust of getting closer to the communities they served. When crisis comes, it may be their immediate communication channel.

The military did not want to ban the use of social media as many of its soldiers use Facebook to communicate with their families, especially when they are assigned to areas far from home.

The challenge at the time was to effectively use a platform that troops already populated.

“Despite the advantages offered by technology, stringent regulation is important to ensure its proper use. Oftentimes, Army personnel violate the security, accuracy, propriety, and policy (SAPP) rule when commenting, posting, or linking indecent photos, languages, articles, and opinions that are not suitable for public viewing or sharing,” the handbook said in describing its rationale.

It added: “The handbook was crafted as part of the Army’s initiative to re-establish and sustain the public’s perception of the Army as a professional organization. Since an individual army personnel represent the whole organization, this handbook aims to instill the idea that their actions affect the Army’s image.”

Do’s and don’ts

The guidelines consist largely of obvious pointers for any member of the military: they should not post anything that would reveal their operations, they should not publicly question the organization’s policy, they should not post solicitations and advertisements.

Soldiers were reminded to take care of their privacy settings across platforms so that their profiles would not be easily searched and hacked by enemies.

The manual also emphasizes the importance of military leaders setting themselves as good examples for the entire organization to follow.

“Troops consider their leaders, commanders, or heads of office as role models. If somebody is expected to perfectly adhere to the provision stated in the policy, that is the platoon leaders, commanders or heads of office. Personal example affects people more than any amount of instruction or form of discipline,” the manual said.

Two prohibitions that stand out, which the military has been repeatedly accused of violating are the following:

“4. Rants or gripes

…

9. Posts instigating fight or debate on perceived critical and political matters that affect the military organization”

“Do not debate, quarrel or engage in other forms of negative discussions detrimental to the image of the Philippine Army,” the handbook said.

Committing any violations posed by the handbook would lead to consequences, it warned.

Soldiers can be court-martialed for violation of Article 96 and Article 97, which refer to conduct unbecoming of an officer and a gentleman, and conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline.

For “grave offenses” – or posts that constitute criminal liability on the part of the soldier – soldiers may be discharged from the service.

Parlade vs CHR

Parlade, chief of the military’s Southern Luzon Command (Solcom), is not afraid to use his social media platform to attack organizations and individuals whom he deems not aligned with his anti-communist agenda.

He is an outspoken member of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), a body created in December 2018 by President Rodrigo Duterte which aims to end the 50-year-old communist rebellion. (READ: The end of the affair? Duterte’s romance with the Reds)

But the NTF-ELCAC does not only focus on alleged members of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). It has openly condemned human rights defenders, activists, and even the media, subjecting them to massive red-tagging and harassment through its official Facebook and Twitter pages.

The vitriol seen on these social media pages spilled into the personal accounts of Parlade.

Since creating his Twitter account @ParladeJR in November 2019, he has tweeted a total of 220 times to his audience of at least 825 followers, including the official accounts of NTF-ELCAC and the Civil Relations Service of the AFP.

Parlade, who described himself a “dreamer” on Twitter, doesn’t hold back in attacking even elected officials and a constitutionally created body such as the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

In September alone, 4 out of his 7 tweets that month were aimed at the CHR and its Chairperson Chito Gascon.

Talking about a statement by the CHR condemning a crime committed by the NPA, Parlade tweeted: “Ang puso ba ni Chair Gascon ay nandito rin? Iisa kaya ang pananaw nya sa mga kasamahan nya sa CHR lalo na kay Mam Spox? Sana naman po. Mulat na ang bayan, ikaw na lng Chairman ang napapagiwanan…”

(Is Chair Gascon feeling the same way? Does he have the same view as his colleagues in CHR, especially the spokesperson? I hope so. The public is already aware, and you’re being left behind.)

The tweet’s message reflected the central theme of Parlade’s attitude towards the CHR, which he accuses of being complacent, given the violations committed by the New People’s Army (NPA).

As early as March 29, he called on Gascon, saying that “the problem with CHR is its Chairman.”

“We have not heard him speak against the CPP and NPA. Spokesperson [Jacqueline] De Guia is doing her job well but we have yet to heaŕ Chairman Gascon denounce all these killings and HR violations of the NPA. How hard is that Mr Chair?” he tweeted.

Parlade’s understanding of the CHR’s stand is wrong. The Commission, on several occasions, has explicitly said it does not support communist rebels.

In a June statement condemning NPA attacks in Misamis Oriental, CHR said that it is “consistent in denouncing these atrocities and in forwarding its plea to both the government and insurgent groups to put an end to the long-standing armed conflict in the country.”

Aside from actively promoting on social media its mandate and positions, Gascon emphasized that CHR has always maintained its communication lines open with the government to clarify misconceptions.

In fact, he recalled a meeting with NTF-ELCAC Executive Director Allen Capuyan in which CHR “stressed to those present that [the commission] condemns all forms of violence, including its use to further ideologies on the ground,” and that as a constitutional office, it is “independent and non-partisan when it calls out the possible abuses of government acts that lead to human rights violations in communities.”

The meeting ended well from the CHR’s view, Gascon said.

“Yet, despite all of our efforts to clarify our positions and ensure opportunities for constructive dialogue, some people insist upon holding a negative view of this institution and are even active in perpetuating disinformation about our work and our mandate,” he told Rappler on Friday, October 16.

The attacks against CHR also go beyond Parlade’s tweets. Its officials have been red-tagged by social media pages reportedly affiliated with regional police offices – incidents that are “continuing causes for concern and validate the observations” of international mechanisms, including the United Nations, about the need to end reprisal against human rights defenders.

“CHR will continue to document and take due notice of these instances as we are duty-bound to stand for truth and accountability at all times,” Gascon said.

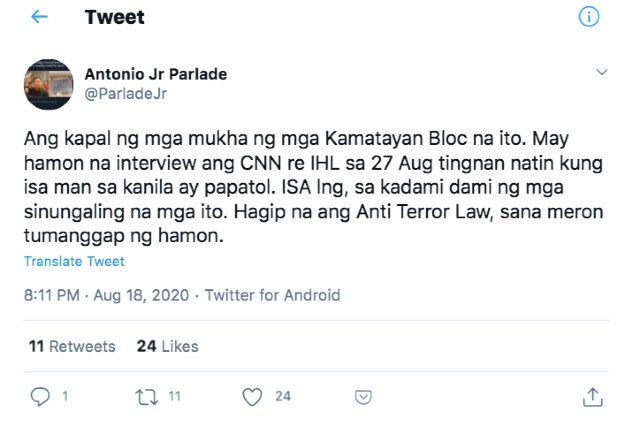

But perhaps bearing the brunt of Parlade’s tweets is the Makabayan Bloc or 6 lawmakers representing progressive partylists in the House of Representatives.

These legislators – Bayan Muna’s Carlos Zarate, Ferdinand Gaite, and Eufemia Cullamat, ACT Teachers’ France Castro, Gabriela Women’s Party’s Arlene Brosas, and Kabataan’s Sarah Elago – have already been the target of attacks from the NTF-ELCAC.

On Twitter, Parlade has at least 17 posts that referred to Makabayan Bloc as “Kamatayan Bloc.” The earliest tweet containing this term was posted on November 27, 2019, in which he accused the legislators of hijacking “our budget for their agenda.”

NTF-ELCAC’s Facebook page also carried several of Parlade’s statements that made reference to the “Kamatayan Bloc.”

Parlade often tried to openly agitate the progessive lawmakers in the context of the widespread killings of human rights activists, the anti-communist movement, and the anti-terror law.

On his personal Facebook profile Parlade attacked human rights defenders who condemned the killings of activists, accusing rights group Karapatan of being a communist front. He also wrote that slain Negros human rights defender Zara Alvarez was not an activist but a member of the NPA.

On August 18, Parlade tweeted that the anti-terror law “will catch up on” Elago. He also said the youth representative “pushes them to be violent and dangerous citizens of this country.”

On January 15, without providing any proof, Parlade also accused the Makabayan Bloc of taking advantage of disaster response.

“Yes at this time of disasters the Kamatayan Bloc’s money-making machinery is once again exploiting our generous friends to scam funds for the revolution using ‘disaster response,’ ‘relief assistance’, etc as front,” he tweeted.

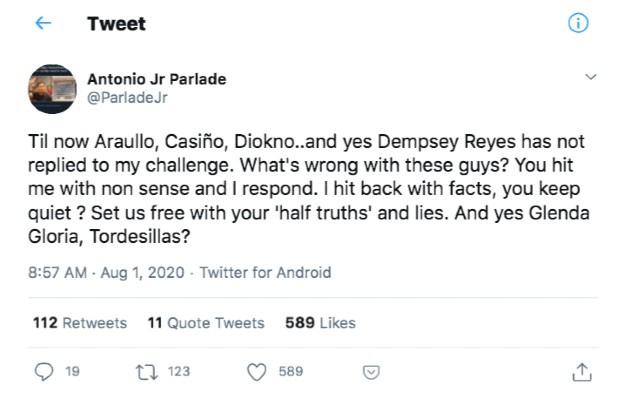

Parlade did not only target human rights groups and other progressive organizations. Media groups, journalists, and even a think tank also became the subject of his tweets.

He also “challenged” individuals and maliciously accused them of spreading “half truths and lies.”

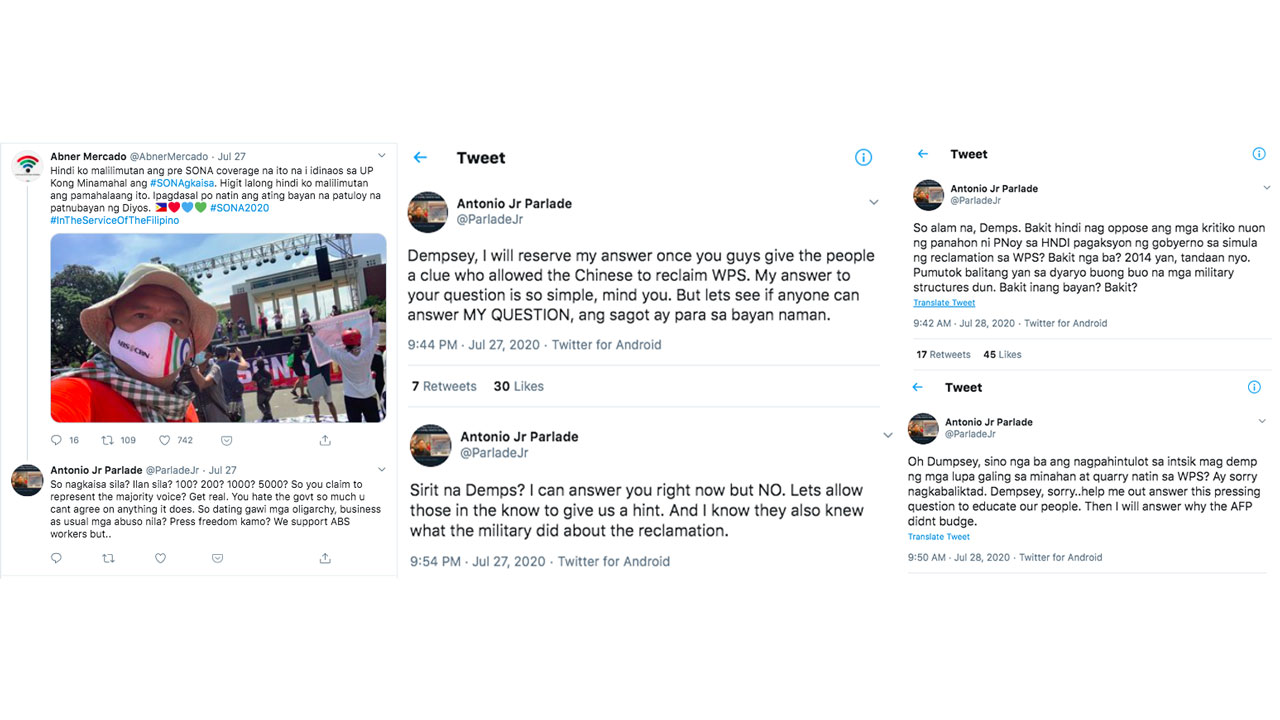

In a series of tweets posted on July 27 and 28, Parlade mockingly included the name of a journalist as he ranted about an issue concerning the West Philippine Sea.

He also replied and challenged a tweet of broadcast journalist Abner Mercado about a protest action against Duterte’s State of the Nation Address (SONA), and hinted about the shutdown of TV network ABS-CBN.

In text messages to Rappler on Thursday, October 15, Parlade insisted that all his social media posts had basis despite being disputed by the people he had made accusations against.

“Mine are factual assertions…What we post are authorized and that hurts the CPP propaganda machinery,” Parlade said.

Complaints vs Parlade

There have been efforts to hold Parlade accountable not just for his posts, but his overall public pronouncements.

In an email to Rappler on Saturday, October 17, Kabataan Party-list said that Parlade and his office have not reached out to them beyond social media to discuss the issues. They also tried to file House resolutions seeking to probe state forces’ red-tagging online but all these are to no avail.

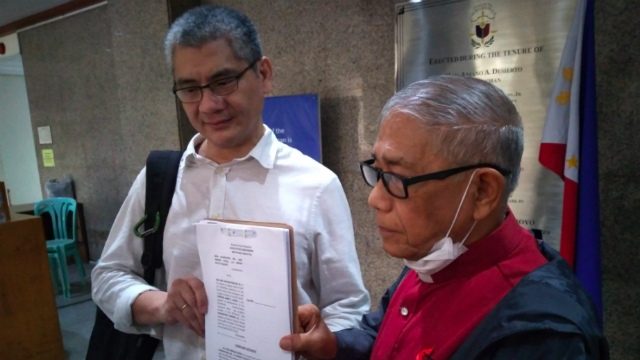

In June, Bayan Muna Representative Carlos Zarate filed a complaint before the Office of the Ombudsman against Parlade for violating the anti-graft law and the Administrative Code for engaging in red-tagging. (READ: Zarate to Ombudsman: Fire Parlade for red-tagging)

In the complaint, Zarate said Parlade “was shown to have acted with manifest partiality, evident bad faith, and inexcusable negligence.”

But as early as February, policy research group Ibon Foundation filed an administrative complaint against Parlade, National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon, and Communications Undersecretary Lorraine Badoy for their “malicious abuse of authority and negligent performance of duties as public officials.”

Parlade and the two officials, the complaint said, violated provisions of Republic Act No. 6713 or the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees.

On Twitter, Parlade accused the group of trying to “radicalize” children through the books they produced for schools across the country. NTF-ELCAC also tagged it as a communist front.

Ibon is one of the foremost policy groups tackling socioeconomic issues in the Philippines. Since its creation during Martial Law, Ibon has been working closely with civil society, leading discussions based on its research.

The think tank asked the Ombudsman to “punish” the officials for their conduct that is “grossly disregardful of the public interest, unprofessional, unjust and insincere, politically biased, unresponsive to the public, distorting nationalism and patriotism, and undemocratic.”

Two days after, Parlade tweeted: “Nasaan kaya si [Sonny] Africa? Yong IBON na mababa ang lipad? Pakaso-kaso pa hindi na lng humarap sa debate o forum. Sige nga? Name your place except Africa or China.”

(Where is Sonny Africa? Ibon, a group with no dignity. Why keep on filing cases instead of facing me in a debate or forum? Name your place except Africa or China.)

Ibon executive director Sonny Africa told Rappler in a phone interview on Thursday, October 15, that there has been no update from the Ombudsman almost 9 months since the complaint was filed against the officials.

Ibon Foundation sees the filed complaint as an opportunity to draw the officials out of their social media rants and into the court.

The policy group also tried to reach out to clarify the allegations brought forward by several officials, including Parlade. But their letters remained unanswered, while a request lodged with the Freedom of Information portal is still waiting for action.

For Africa, the social media posts of Parlade and other officials, while ignoring Ibon Foundation’s official letters, prove that they are just “inciting a propaganda war.”

“Sa sobrang harsh ng accusations nila, the proper venue for that if they have evidence is to bring those to the court system,” Africa said. “But wala silang finafile na any case, which means they have no evidence that will hold up in court.”

(With such harsh accusations, bringing their evidence to the court system is the proper venue. But they haven’t filed any case yet, which means they have no evidence that will hold up in court.)

According to former national security adviser Cesar Garcia, the military does not always have to resort to social media retaliation.

“If your intention is to expose them, it is better to engage them in public discourses, or if not, file a case,” Garcia said.

He added: “If they are actually violating the law, they are convinced that they have violated the law, and that they have evidence to back it up, file the case so that they can settle it there.”

Parlade has tried to do something close to Garcia’s recommendation. In November 2019, Parlade walked into a forum against red-tagging by lawyers’ group National Union of People’s Lawyers. Instead of engaging in dialogue, Parlade, mid-way through the forum, stepped forward and waved a document that opposed the views of the speakers.

He was kicked out.

As for criminal complaints, the AFP relies on the Philippine National Police to translate their information into accusations that can withstand the scrutiny of the courts. Not all activists they accuse of being “communist-terrorists” are actually taken to court, which also leaves them without a platform to disprove the accusations.

The danger of online attacks

Elsewhere on the internet, progressive groups and human rights activists face massive vilification, with Duterte allies tagging them as members of the CPP-NPA. The problematic use of social media by the military does not help the situation and instead further endangers the lives of many. (READ: Lives in danger as red-tagging campaign intensifies)

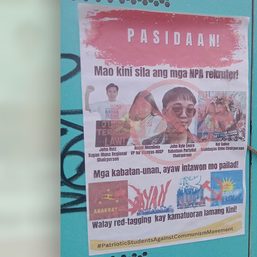

These red-tagging campaigns are not confined within the webpages of Facebook and Twitter, but are also matched with ground operations. Even at the height of the pandemic, posters and tarpaulins that label individuals and organizations as “berdugo” (executioners) were spread throughout key cities and municipalities.

The CHR, in a July report, said that Duterte “created a dangerous fiction that it is legitimate to hunt down and commit atrocities against [them] because they are enemies of the State.”

And dangerous it really is.

Rights group Karapatan said at least 318 individuals have been killed “in the course of the Philippine government’s implementation of its counterinsurgency program” since 2016.

On August 17, Zara Alvarez became part of the long list of activists and human rights defenders killed under Duterte, and the 13th from Karapatan alone.

Her death came after years of receiving threats. A long-time human rights worker, Alvarez was previously tagged as a terrorist in posters and even by the Department of Justice in 2018.

Days before, on August 10, Anakpawis leader Randall “Randy” Echanis was brutally murdered inside his rented home in Quezon City.

The existence of the anti-terror law, compounded by the widespread war on dissent, makes every public pronouncement against any group or individual dangerous – especially if done by a state agent.

How many more lives will have to be lost before the military reassesses its use of social media? – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Jhed and Jonila’s fight for justice](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/TL-jhed-and-jonilla.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=411px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.