SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – On Friday morning, May 11, Maria Lourdes Sereno entered the en banc as a Chief Justice for the last time. Before the Supreme Court (SC) justices took a vote, Sereno left the room.

Ousted in a historic 8-6 decision, Sereno leaves the High Court the same way she came in – an outsider.

The outsider

Sereno’s first two years in the Supreme Court were not easy. Multiple court insiders said she had always been an odd one out in the old boys club – given an old car at the start and an improper office.

The Supreme Court has always had factions; Sereno came in when the Court was divided at the height of the Renato Corona-Antonio Carpio rivalry.

It would appear that Sereno had taken the side of Carpio, voting similarly on issues that opposed the positions of the late former chief justice Corona.

Corona would admit: “[Sereno’s] arrival to the Honorable Court has signaled a new period of difficulty and embarrassment for [me].”

Sereno was one fiery dissenter during Corona’s time, writing in public opinions about irregularities that allegedly occurred in decisions related to former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. (READ: The consistency and ironies of Justice Sereno)

The historic appointment

Fast forward to 2012, when Sereno accepted nominations for the vacant chief justice post. Eyebrows were raised as the junior justice was up against the senior applicants.

Then her problem started: on August 24, 2012, former president Benigno Aquino III appointed her chief justice, bypassing the more senior justices – Carpio, Associate Justices Roberto Abad, Arturo Brion, and Teresita Leonardo De Castro.

To spectators, it seemed like a fairy tale – the youngest chief justice, the first woman to become one, was also openly criticizing her peers at a time when the Court was battling perceptions of being partial to Arroyo.

But inside, tensions were brewing.

Sereno later claimed that De Castro had told her: “I will never forgive you for accepting the chief justiceship. You should have not even applied in the first place.”

Jardeleza and the JBC

Carpio and Sereno would maintain civility, even as employees supportive of Carpio thought the Chief Justice betrayed their friendship when she applied for the post, an insider said.

In 2014, Sereno and Carpio pooled forces together once more, at least according to Associate Justice Francis Jardeleza.

Sereno invoked the unanimity rule to block Jardeleza’s nomination to the Supreme Court, saying there were questions about his integrity. Those questions concerned Jardeleza’s decisions as solicitor general in the West Philippine Sea (South China Sea) arbitration case, and the nitty-gritty of including Itu Aba in the country’s memorial to the tribunal.

Carpio, among the country’s experts on the subject, allegedly influenced Sereno to block Jardeleza’s nomination.

Jardeleza wrote in his dissenting opinion: “I emphasize that neither [Sereno] nor her informant, Senior Associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio, were part of the Philippine legal team. They did not participate in the discussions that led to the initial adoption of the low-risk strategy, nor in the decision not to amend the Philippine submission. In fact, I did not furnish respondent or Justice Carpio a copy of this confidential Memorandum in view of its highly sensitive content.”

Brion said Sereno manipulated the proceedings and engaged in a purposive campaign to discredit Jardeleza. Brion would later testify in Sereno’s impeachment hearing at the House that Sereno continued her “transgressions” inside the Court.

Jardeleza was excluded from the shortlist, but he sued Sereno and the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC). The Supreme Court sided with Jardeleza and he was later appointed to the Court. (READ: Jardeleza’s SC entry and Sereno’s eroding clout)

An important contention that has surfaced in Sereno’s ouster is this: what right does the Supreme Court have to oust the chief justice on the basis of ineligibility when it was the discretion of the JBC to rule that she was, indeed, eligible?

Three years later, Jardeleza’s victory over Sereno would provide the Supreme Court the basis to overrule the JBC, and oust the chief justice.

“The seminal case of Jardeleza v. Chief Justice Ma. Lourdes P A. Sereno, et al explains that the power of supervision being a power of oversight does not authorize the holder of the supervisory power to lay down the rules nor to modify or replace the rules of its subordinate…In fine, the Court has authority, as an incident of its power of supervision over the JBC, to insure that the JBC faithfully executes its duties as the Constitution requires of it,” said Associate Justice Noel Tijam in his ponencia.

Outsider reformer

For Sereno, this heavy opposition against her inside the Court was prompted by her being an “outsider reformer.”

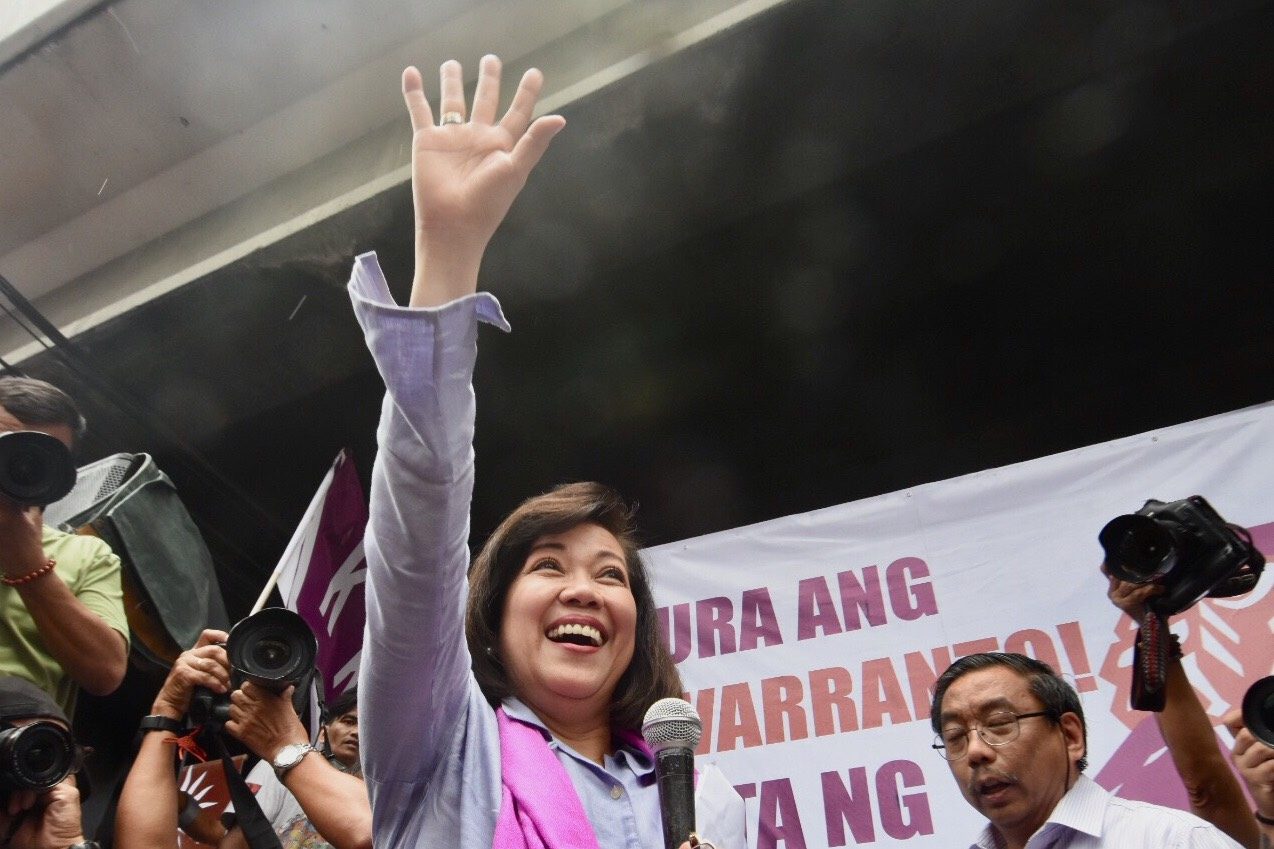

“An outsider reformer, and someone who is not willing to play politics should already be anticipating this possible outcome. Because when you try to change things, when you try to say the old culture cannot go on the way it has been going, makakabangga mo (you will clash),” Sereno said on Friday, May 11, after she was ousted by a vote of 8-6. Among the concurring justices was Jardeleza.

Sereno said of her ouster, “It is not truly unexpected.”

Some of her reforms included the reopening of a decentralization office, but one that was blocked for alleged transgressions on Sereno’s part. De Castro had questioned why Sereno removed the office from under the supervision of Court Administrator Midas Marquez. The House hearings would reveal that Marquez was sidelined in some of Sereno’s other reforms, including survivorship benefits.

One court insider commented that Sereno could have worked harder on getting the trust and confidence of Marquez, said to be influential inside the Court.

Another reform is the Enterprise Information Systems Plan (EISP), a multi-billion-peso digitization project that aims to make the Court fully electronic, delivering faster services to the people.

This is what Sereno is most proud of: “You cannot find a more dramatic set of reforms as that of the judiciary. It would have been a good story, I would have told the nation to be confident in ourselves, be confident in what the Filipinos can do. We can correct the system that you have decried as unjust.”

But again, inside, it was a different story. She hired consultant Helen Macasaet to oversee the project, paying her a total of P11 million for 4 years’ worth of contracts.

The Supreme Court’s own information technology (IT) chief, Carlos Garay, did not agree with the hiring. In March 2018, when the impeachment proceedings against Sereno were discussing the EISP and possible irregularities in procurement, Garay resigned.

All Duterte?

Sereno directly linked President Rodrigo Duterte to the ouster move against her.

“If he does not want it, it could have ended. But it did not end. Clear as day,” Sereno said, adding that there were even offers to meet with the President to solve the problem.

Duterte had marked Sereno as his enemy. It started when Sereno spoke out against putting judges in the President’s narco-list, against extrajudicial killings, and against martial law.

But Court insiders and observers would say that Sereno was never in the way of Duterte, as far as key Supreme Court decisions were concerned.

Sereno had always lost, sometimes overwhelmingly, and issues that were of interest to Duterte had always prevailed: Ferdinand Marcos’ hero’s burial, martial law in Mindanao, the continued detention of staunch administration critic Leila de Lima.

“The claim that the present actions against her was because of her constant position against the administration is belied by her voting record in this Court,” Associate Justice Marvic Leonen said in his dissenting opinion.

Leonen pointed out that Sereno:

- Did not dissent on the constitutionality of Duterte’s martial law in Mindanao, but only limited it to Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, and Sulu

- Voted with the majority that ruled a congressional session was unnecessary to affirm Duterte’s declaration of martial law

- Voted with the majority that “the Supreme Court cannot interfere in the manner by which the House chooses its minority leader, despite the absence of a genuine minority”

- Voted with the majority which upheld the curfew ordinance in Quezon City on the ground that the ordinance did not violate the constitutional rights of minors

“The claim that the present status quo caused her difficulties due to her positions is, therefore, puzzling,” Leonen said.

Sereno’s rise to the top justice post was extraordinary, except to her peers who never appeared to accept her.

It didn’t seem that Sereno was interested in winning them over either, as she said in an earlier interview: “There are only a limited number of things we can do to address the emotions of others. Largely how you deal with your emotions is your personal accountability.”

In the end, it was the same peers critical of her who gave the fairy tale beginning a bitter end.

But Associate Justice Benjamin Caguioa said in his dissenting opinion, “No matter how dislikable a member of the Court is, the rules cannot be changed just to get rid of him, or her in this case.”

Different sides of the predicament

Sereno’s quo warranto ouster, slammed as unconstitutional by many legal experts, including 6 incumbent justices, is said to be proof of a continuing threat against democracy.

Sereno said that given the Supreme Court’s tainted reputation, sparing her from quo warranto would have been its redemption.

Several deans of law schools had warned that the removal of Sereno via quo warranto will only expose those who were involved “to the same vicious cycle of extrajudicial removal process which will subvert the constitutional check and balance, and endanger judicial independence.”

Former Ateneo School of Government dean Tony La Viña had written: “A quo warranto decision that removes an impeachable official is not about Sereno but about all present and future officials; it is about the rule of law and the Constitution, and what kind of country we want to have in the future.”

On the other hand, Tijam, in his ponencia, said: “The Members of the Court are beholden to no one, except to the sovereign Filipino people who ordained and promulgated the Constitution.”

He said the Supreme Court cannot be accused of always siding with Duterte, the proof being, that they unanimously compelled the government to turn over drug war documents.

Despite calling the ouster a “legal abomination“, Leonen said Sereno failed to show leadership in this entire episode.

“She should be at the forefront to defend the Court against unfounded speculation and attacks. Unfortunately, in her campaign for victory in this case, her speeches may have goaded the public to do so and without remorse,” he said.

What now?

“Kailangang higit ang pagmamatyag natin sa panahon ng tag-dilim. Buuin natin ang isang kilusang Pilipino na patuloy na ipagtatanggol ang katarungan at maniningil sa ating mga tinalagang lingkod bayan,” Sereno said in her speech to supporters after she was ousted.

(We have to be more vigilant in this time of darkness. Let’s build a movement of Filipinos who will continue to defend justice and hold our chosen public servants to account.)

Leonen, however, appealed to Sereno and the public: “To succeed in discrediting the entire institution for some of its controversial decisions may contribute to weakening the legitimacy of its other opinions to grant succor to those oppressed and to those who suffer injustice.”

Five years’ worth of internal tensions have ended, but at massive cost. The fairy tale is over, and the nation is left to wonder how the Supreme Court can begin rewriting its story from this nasty episode.

An optimistic-sounding Leonen said: “Today, perhaps, a torch may just have been passed so that those who are left may shine more brightly. Perhaps, an old torch will be finally rekindled: one which will light the way for a more vigilant citizenry that is sober, analytical, and organized enough to demand decency and a true passion for justice from all of government.”

After Sereno, the High Court and its leadership will have to rebuild quickly and fortify the institution against further erosion of its credibility and integrity. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.