SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

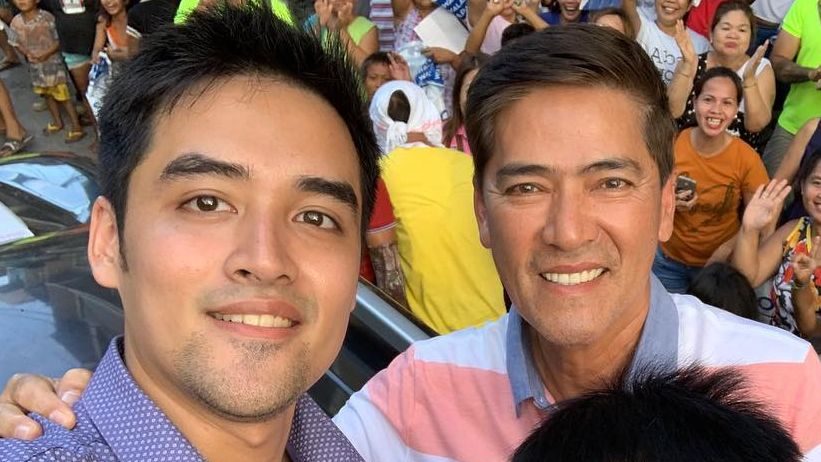

MANILA, Philippines – Pasig’s young new mayor, Vico Sotto, posts about some achievement on his official Facebook page – for instance, a thousand-plus scholars added to the roster – and easily 10,000 people hit the “Like” button. Meanwhile, in some corner of the city, the previous mayor he had supplanted, Bobby Eusebio, attends a fiesta or a funeral, shaking hands with people and giving away knick-knacks as though he didn’t lose the last election.

Everywhere around the city, the letter E – for “Eusebio” – remains emblazoned on curbside railings, schoolhouses, public halls, and almost every government service vehicle: vestiges of the family’s 27-year reign in Pasig.

Sotto, after just a single term of 3 years as city councilor, thwarted Eusebio’s bid to take that number to 30. If there was anyone who could beat a Eusebio in an election, it was Sotto, and a group of influential old-timers, who call themselves Tambuli ng Pasig (Clarion of Pasig), had recognized that and honed in on him as a potential liberator from the tired, old regime.

“Heto, may karisma, guwapo, matangkad, maputi, artistahin,” said Eli Salonga, a member of Tambuli. (This one has charisma, is handsome, tall, fair-skinned, star material.)

But, more importantly, “isang mabait na tao, mabuting tao,” added Noel Medina, the civic group’s president. (A kind person, a good person.)

The son of two big movie stars, Coney Reyes and Vic Sotto, Vico Sotto was somebody without even trying. And although he is a new, squeaky-clean personality in politics, his surname links him to two senators: one, from the distant past, his great grandfather Vicente Sotto; and the other, his uncle, current Senate President Vicente Sotto III.

The neophyte councilor was a rare confluence of two essential requirements for political success: leadership potential and marketability. But his good moral character sealed the deal: Vico Sotto could make a good mayor.

And so Tambuli, among whose founders are relatives of the late Senate President Jovito Salonga, got behind Sotto for the May 2019 elections and campaigned for him.

“Alam mo ba kung ano’ng ginawa mo? Inagaw mo ang 27-year-old multi-billion kingdom kina Eusebio,” Medina told Sotto after he won the mayoralty. (You know what you just did? You grabbed a 27-year-old multi-billion kingdom from the Eusebios.)

It was congratulatory, but Medina also meant it as a warning.

“Ang tingin namin sa laban na ’to, giyera (We see this fight as a war). This is a political war,” he went on. “At ’yung kalaban natin, buhay pa at kumpleto ang armas para durugin ka (and our enemy is still alive and fully armed to crush you).”

Marching orders: end corruption

One morning in October, a middle-aged woman threw a fit at city hall’s service floor, where people queue up at different counters for every mundane errand involving the city government.

The woman was trying to pay her overdue taxes under a compromise agreement and, perhaps feeling a little humiliated by her situation, she flared up when she saw the clerk call for the documents of a caucasian man who was standing behind her. Incensed at being overlooked, she flew into a rage so big that Winnie Rayos Dimanlig, head of the city’s complaints desk, came running to her from her office on the far end of the hall.

Dimanlig found the woman berating the clerk, who was trying to explain that the foreigner had actually arrived earlier than her and was on his way back from the cashier to submit his receipt.

The clerk’s patience was running out. Dimanlig tried to calm the situation.

“’Yung pagsasalita nung nanay, mataas din ang ere. Ang kausap niya dun ay ’yung isang tao na may pinagdaraanan na mabigat na problema at the moment,” Dimanlig recalled, chuckling a bit at the meltdown she tried to sort out. (The woman’s tone was condescending. The clerk she was dealing with happened to be going through some big problem at the moment.)

Just then, the woman started to faint. Dimanlig called for an ambulance, and the woman was brought to a nearby hospital.

It was one of the more extreme cases Dimanlig and her team of 10 personnel have had to handle at the Ugnayan sa Pasig (Touchpoint at Pasig), the complaints desk and hotline Sotto set up on his 3rd week as mayor.

The Ugnayan is the embodiment of Sotto’s marching orders to the city’s bureaucracy to shape up, not just in giving courteous, professional frontline service to citizens but, more importantly, to end corruption.

“The employees are still from the previous ano, ’di ba?” Dimanlig said, avoiding mention of Eusebio’s administration. She is one of Sotto’s few fresh hires, her position justified by the new office she leads.

“So the reality is that some of them would still do what they would,” she trails off, implying old habits and indiscretions.

“At saka ’yung mga nanghihingi ng, you know, nagse-send ng feelers na, aasikasuhin ko ’to pero – May ganun pa rin,” Dimanlig went on. (And there are still those who ask for, you know, who send feelers that they would fix this but–.)

Bribes, she couldn’t bring herself to say, because she shares an entire floor with bureaucrats among whom are a few who have been reported to her office, and are now being investigated for alleged corruption.

In fact, “ugnayan” has become a verb among city hall employees. “Uy, na-ugnayan ka raw (Hey, I heard you were ugnayan-ed),” they would tease a colleague who’d been reported to the desk or hotline, Dimanlig said. She takes it as a good sign.

“We have a pretty good batting average,” Dimanlig was proud to say, adding that reports of officers trying to fleece citizens have declined in the past couple of months.

“Just one or two [are reported now],” she said.

‘Like their private property’

The villagers were ready with an armada of questions and reasons to convince Mayor Sotto not to widen the canal between their informal settlement and a flood control dike beyond two meters. Any more and it might mean their eviction. So they steeled themselves. They were resolute. They won’t take no for an answer.

But the moment Sotto alighted from his van in the riverside community in Barangay Santolan one Friday morning in August, the small crowd of villagers were starstruck. The women sighed and giggled, “Ang guwapo! (How handsome!)” Even the men couldn’t help craning their necks to get a better view, a broad grin on their faces.

Although he could not completely grant the villagers’ request, he did assure them that anyone who would be evicted to make way for the wider canal would be relocated within Pasig, and he promised that he wouldn’t leave them homeless.

Sotto’s charisma and earnest manner come handy when he needs to be stern. He has something of his comedian father in his ability to douse tense moments with jokes or self-deprecating quips.

He needs it because, to an undetermined number of people in his bureaucracy, he is bad news. To demand professionalism from people who think they are shortchanged, or integrity from those who have been benefitting from the corrupt system, is political suicide.

He needs these people to like him, or at least get as many other people as possible to like him in order to drown out the haters.

And so he must win them over even as he tries to discipline them.

When Sotto won the election and promised reforms, a shockwave went through city hall among employees who feared for their jobs.

But Sotto, the mabait (kind), promised to keep them – even the rotten, if they would shape up.

Although he slammed the city’s “notorious” traffic enforcers for fleecing motorists, he offered them an opportunity to secure their tenure by reforming themselves. Those caught still exacting bribes despite the mayor’s warning were fired and investigated.

In August, Sotto posted a photo of an empty office at city hall. The occupant had been fired for “questionable practices and abusive behavior,” and he took everything with him on his way out.

For Sotto, it was a glaring example of what he was up against: “people who treat the government like their private property.”

‘Two governments’ in Pasig

“Kay Enteng kami (We’re for Enteng),” the words were printed across the chest on a shirt a man was wearing during that public consultation meeting about the canal in Barangay Santolan.

Vicente “Enteng” Eusebio became mayor of Pasig in 1992 and remained in power until he used up the 3 consecutive terms allowed by the law. His wife Soledad took over for one term until 2004, when Enteng ran again and won.

In 2007, Enteng’s son Bobby won as mayor for two successive terms, after which Bobby’s wife Maribel went for a single term. Bobby was back in 2016, and then tried for re-election last May, when he lost to Sotto.

The Eusebios knew how to push Pasigueños’ buttons, Tambuli’s Salonga said. They should know; they helped Enteng win his first term in 1992. Back then, he was the Bulakeño migrant who offered something new, before he got too comfortable in city hall.

The Eusebios strived to be seen at as many “kasal, binyag, libing (wedding, christening, funeral)” as they could, said Tambuli’s Medina, also the president of the the Institute for Political and Electoral Reform.

It’s a basic trapo – traditional politician – tactic they wish Sotto would use for his own good, if the goal is to earn the people’s loyalty.

But Sotto has his way of doing things. During the campaign, Bobby Eusebio put on full variety shows “complete with macho dancers” during his sorties, Medina said. Sotto, meanwhile, wanted to stand at street corners and atop trucks like a preacher, and there propagate his gospel of reform and good governance.

The Tambuli guys said they insisted on at least a bare stage with a decent sound system, but Sotto wouldn’t hear any of that.

Watching Sotto do his thing, his veteran campaigners learned what it means to be unconventional.

“Aba, parang tama ito eh (Well, this seems right),” Medina recalled exclaiming.

Now that he is mayor, Sotto still does things as he sees fit, especially when it comes to his public relations: no media scrum. Hardly any TV interviews. No song and dance crew. No banners or fliers. No glitz and glamor, although he could definitely bring that on with his showbusiness connections.

Instead, he goes down to tricycle stations and clogged streets to see the problems for himself, holds townhall meetings, command conferences, and graces the occasional street party unannounced, and then everything ends up as photos or videos on his official Facebook and Twitter profiles, where he has several hundred thousand followers.

Because he wants to focus on the work, Sotto would say when turning down a request for a media interview. He wants to work silently, and the work will speak for itself.

Why bother with the conventional fanfare? Didn’t he win by being unconventional?

So far, Sotto has reinvigorated the city’s public health care system, beefed up its scholarship program, sorted out tussles involving tricycle unions, cleared many roads and sidewalks of obstructions, set up freedom of information kiosks at libraries, and perhaps, most importantly, motivated young people to get involved in how the city government is run.

Sotto is doing well and covering his campaign promises, Salonga and Medina said, but he is not doing enough.

“Ang problema namin is, Eusebio is breathing down our necks. Andiyan lang eh. Nasa likod mo lang eh. Kadikit mo na,” Salonga said. (Our problem is, Eusebio is breathing down our necks. He’s just there, right behind you, almost at you.)

A quick look at Bobby Eusebio’s official Facebook page shows the former mayor still going about his usual business attending every kasal, binyag, libing, and more, sponsoring events and even reposting photos of old projects, creating the impression that he is still in charge, still on top.

Salonga said he even saw the Eusebio couple lead a recent town fiesta parade aboard government vehicles still bearing their names and taglines.

“Ironically, dalawa ang gobyerno sa Pasig: ang gobyerno ni Mayor Vico at ’yung gobyernong nakaraan,” Salonga lamented. (Ironically, there are two governments in Pasig: that of Mayor Vico and the past government.)

“Habang itong mayor natin, abala sa good governance, matinong pamamahala, hindi nagtatrapo, itong kalaban, bumubugbog ng trapo politics,” Medina said. (While our mayor is busy with good governance, avoiding trapo ways, the opponent is busy with trapo politics.)

“Eh kulang na lang, barilin ka nung kalaban mo eh. Kulang na lang, ganun ang gawin sa kanya, kung paano siya ino-operate sa ibaba,” he added. (Your opponent would all but shoot you. That’s about the only thing they haven’t done to him, the way they operate against him on the ground.)

A doer, not a politician

Although Sotto has taken on the role of Pasig’s liberator and reformer, he has never taken a direct shot at the Eusebios.

In July, when he announced a massive inventory of the city government’s assets and supplies to account for the missing P1.4 billion flagged by the Commission on Audit, Sotto made sure to point out that it was not necessarily an indictment of the previous administration.

Meanwhile, his own administration is set back by the inventory because all procurements have been put on hold until it is finished, hopefully by the end of the year.

For instance, several computer stations at the Ugnayan office are offline because the moratorium covers internet service subscriptions.

It makes the work harder and slows down delivery, which the public may interpret as languor on Sotto’s part.

Because Sotto shuns the limelight, there is talk on social media that “wala siyang ginagawa (he is not doing anything),” especially because people compare him to Isko Moreno, Manila’s swashbuckling, media savvy new mayor. (READ: [OPINYON] Vico at Isko: Governance in the age of social media)

There is a constant stream of disinformation going around to discredit Sotto, who, every now and then, debunks them with a social media post crying “fake news.” So he knows his opponents are out to get him, and his tactic is to just keep working.

“Mayor Vico is not a politician. He’s a doer. We see that. Nakikita namin ’yung kilos niya, ’yung sipag niya. Kaya nga lang (We see his actions, his efforts. The thing is), politics will always play a role,” Salonga said.

Facebook and Twitter are good platforms, but they “do not resonate at the grassroots,” where the former power is busy shoring up goodwill with every handshake and goody bag.

Besides, how many of Sotto’s social media followers are actually Pasig voters?

“Naaalarma kami. Kung si Eusebio nadurog, naghirap, napanagot, we’re willing to wait kahit hanggang next election,” Salonga added. (We are alarmed. If Eusebio had been crushed, diminished, punished, we’re willing to wait until the next election [to do something aggressive].)

But the fact is the old guard is up and about, and “their tentacles of corruption, nasa city hall pa ’yung iba (some are still in city hall). And they’re still occupying good positions,” Salonga warned.

Although Sotto has taken a hardline stance against corruption, vowing to “never accept kickbacks” from government projects, and opening up public biddings to tougher scrutiny, Tambuli worries that the cunning, well-entrenched operators within city hall could easily circumvent the new rules.

Sotto, they say, believes in giving people second chances, as he did with the traffic enforcers. And that does endear him to people, especially the rank and file at city hall.

But Tambuli worries that his leniency might be taken advantage of. Instead, they want to see a purge of city hall in order to ensure the new administration’s survival, and to truly weed out corruption.

On September 25, Tambuli ng Pasig filed a graft case at the Office of the Ombudsman against Bobby and Maribel Eusebio, and several other city officials, for an allegedly anomalous “sister city” partnership with the Municipality of Pamplona, Camarines Sur. The group accused them of channeling at least P25 million pesos to fund Mrs. Eusebio’s failed attempt at running for Pamplona congresswoman.

Likewise, they want to see Sotto bare his fangs and take on his political opponents, even as he courts the public’s loyalty. At the very least, he could have the E insignia all over Pasig erased, just as he renamed the city’s scholarship program to be politically neutral.

If the changes he promised take too long to be felt, the tide might turn against him. Voters can be fickle and easily distracted, Tambuli warned.

So better make the adjustments now: be more aggressive. Amplify the message. Get ahead of the opponent.

The Son of Enteng

But the last thing Pasig needs is another Enteng or Bobby Eusebio, said Carmel Abao, Sotto’s political science professor at the Ateneo de Manila University.

If, in order to secure his position, Sotto resorted to a negative campaign against his predecessors, as some of his supporters might urge him to do, the danger is he might become the very thing he is trying to fight.

“That takes up so much energy and resource,” Abao said, but “to really deliver services is also a way of countering the political opponent so, if anything, he should double his efforts to really show the people that they’ve had enough of this Eusebio nonsense. It’s been 27 years!”

That means fighting the token handshakes and dole-outs with livelihood and health programs, education and scholarships, uninterrupted water and electricity – government services that give the people a sense of security that, hopefully, will keep them from becoming prey to patronage politics.

It’s a tough call, but Sotto must rally Pasigueños around a vision of an improved city, something that goes beyond himself or any single politician. That means filling ordinary people in on his ideas and getting them to participate in turning those ideas into actual programs.

Sotto needs to go beyond social media to do this, and be genuinely rooted in Pasig society, Abao said.

After nearly 3 decades of ruling Pasig, the Eusebios will continue to be a force to contend with, along with the disinformation campaign to discredit Sotto and his administration.

Sotto “has to recognize and face these contraints. He cannot not address these issues,” Abao added.

There will always be “constraints” to the governance agenda, as Sotto must now be well aware of. “Politics is always about compromise. Just because he wants something doesn’t mean he is going to get it,” said Abao. For example: hard-headed bureacrats who can maneuver to block reforms.

The trick, Abao said, is to give incentives for good governance, or reward good behavior. Sotto just needs to figure out how, given Pasig’s nuances and idiosyncracies. “Everyone can see Vico is new to this. You don’t learn everything in just 100 days.”

But, all things considered, Abao thinks Sotto is off to a good start.

“Nagkonsehal siya. Nag-political science siya. Hindi siya pulpol. May laman siya eh,” the professor said of her former student, who just needs a little more room to experiment. (He was a councilor. He took political science. He is not a dud. He’s got substance.)

“His practice of politics is better than his rhetoric. I think his actions have been bolder than his words,” said Abao, recalling the instance when Sotto intervened at an employees’ strike against the beverage company Zagu. Sotto took the side of the workers and insisted on their rights, whereas most mayors would go easy on the company that brings revenue to the treasury.

Certainly, trying times lie ahead for the new administration, and the mayor must work to secure his reelection because 3 years will not be enough to institutionalize the reforms which, even now, are challenged by those who cling to the old regime.

Sotto must keep in mind that he has an opponent raring to get back in power, raising the stakes even higher. That said, the new mayor must also not let the next election turn into an obsession, Abao added.

For now, the honeymoon haze of Sotto’s surprise upset against the 27-year dynasty lingers. People jostle one another for a selfie with him. Bureaucrats want to be on his good side. The public keeps wanting to see or hear more of him.

That shirt, “Kay Enteng kami (We’re for Enteng),” was just a joke after all, a pun on the tension between the city’s old and new leaders. On the back was printed the punchline: “Sa anak ni Enteng Kabisote (For the son of Enteng Kabisote),” referring to Vic Sotto’s iconic character in blockbuster movies: a bumbling nobody who married a fairy princess, forced to fight powerful villains and monsters to accomplish heroic feats.

And the truth is, the people expect just as much from Vico Sotto, the Prince of Pasig. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.