SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Last of 3 Parts

PART 2 | Air, land, river operations push Samar rebels on the defensive

PART 1 | 8-month chase leads to sinking of ‘communist VIPs’ in Samar waters

SAMAR, Philippines – Messy (not her real name) was only a 15-year-old high school student in General Mac Arthur, Eastern Samar when she accepted the offer of community organizers to join the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP).

The 28-year-old medic of the New People’s Army (NPA) “Damol” Platoon, operating in Villareal, Samar province, on the opposite side of the island, now works for the government, trotted out by the Armed Forces to convince alienated rural folk to “return to the fold.”

Messy did not sugarcoat the realities that have made Samar a stronghold of the 54-year-old CPP-NPA when she spoke with Rappler on Friday, September 16.

“Kahirapan at kawalang hustisya sa ilang mga taga-Samar na na-experience nila na di naibigay ng gobyerno. At ito ang nakatatak na sa isip ng mga tao,” she said. (Poverty and the absence of justice for some people in Samar, and neglect by the government. This is what people here feel.)

The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) 2021 first semester report said 36 out of 100 individuals in Eastern Visayas remained poor. Eastern Samar had a 43.1% poverty incidence, Samar, 37%, and Northern Samar, 31%. In 2018, Messy’s hometown on the Philippine Sea coast had a poverty incidence of 57.9% – six of 10 residents were poor.

A quarter of Samaron boys do not attend primary school, with the figure increasing to more than half by high school, a 2018 study reported.

The country’s third largest island has been in the news since August 22, when an explosion ripped apart a boat carrying communist rebels off the coast of Tarangan town, Samar.

A social media account focused on defense issues claimed that Benito and Wilma Tiamzon, the top leaders of the CPP, were among the eight casualties.

No laboratory tests have yet been conducted on the recovered remains to establish identity. Military officials have only said they were closely tracking the couple in the days leading to the blast.

Strategic coast

Top CPP rebels headed for Samar when Duterte scuttled peace talks in 2017 and ordered the arrests of more than two dozen guerrillas freed on bail to attend negotiations in Oslo, Norway.

The island’s geography makes it an important cog in the communist underground: a long, narrow coast ringed by mountains with gorges, rushing rivers and the country’s largest remaining connected sections of old growth forest.

TRI-BOUNDARY. Military operations from July to August in the highlands of San Jose De Buan in Samar province forced communist leaders to flee to the coast of Samar. Photo by Jazmin Bonifacio

Eastern Samar faces the Philippine Sea, part of the Western Pacific Ocean, as does Northern Samar.

Samar province nestles in the Samar Sea. In the south, the San Juanico Bridge connects to Leyte island. To the West is Masbate, and to the north, Bicol. Maqueda Bay’s small passages allow boats discreet passage beyond Leyte, to the southwestern Visayas Sea that leads to Cebu and other Central Visayas islands, and then Western Visayas, which includes Negros island.

Visayans have traditionally used these inner maritime routes to hop across regions for trade and livelihood.

Communist rebels also transport arms, units, and officers through these same waters.

Villareal, the former operations base of Messy, is a key logistics hub for the CPP. Bordered by Pinabacdao and the mountains to the east, a narrow backdoor near Sta. Rita town allows swift access to Western Visayas.

“This small town is where comrades come when they feel the heat from the military. This is where our logistics come in,” Dory (not his real name), former deputy chief of the Dumol unit, told Rappler in a mix of Waray and Filipino. ”This is also the gateway for comrades coming from Mindanao and Luzon. The arms we purchase pass through here.”

There, in February, Joint Task Force Storm arrested 70-year-old and alleged CPP central committee member Esteban Manuel as he awaited transport after military operations drove him out of Pinabacdao.

Cycles of oppression

In the last two decades, two national leaders imposed extremely brutal tactics to crush Samar’s insurgents.

From February 18 to April 20, 2005, under then-president Gloria Arroyo, retired major Jovito Palparan rampaged through the island, chalking up 570 cases of human rights violations, including 19 cases of extrajudicial killings, 12 enforced disappearances, and 25 torture cases.

Legal activists were largely the victims of Palparan, now in jail after his 2018 conviction for the 2006 Luzon kidnapping and serious illegal detention of UP students Karen Empeno and Sherlyn Cadapan.

But by 2011 and 2012 – less than 10 years after Arroyo ended her nine-year rule – sparsely-populated Samar accounted for 11% of all conflict incidents nationwide, William Holden wrote in his 2013 study, “The Never Ending War in the Wounded Land: The New People’s Army on Samar,” published by the University of Calgary, Canada.

“It is almost impossible to get out of poverty here,” explained Dory, who left for the mountains in 2007.

“Many of us are poor farmers and fisherfolk, and we are the first hit during crises. One disaster sets you back for years. There are too many people with very low wages or none at all, lacking basic needs like food and education,” he pointed out.

The current leaders of the 8th Infantry Division do not face accusations of wide-scale butchery. But rights group Karapatan furnished Rappler a list of human rights violations on the island:

- The Samar peasant group Sagudti Han Ngan Parag-uma-Sinirangan Bisayas (SAGUPA-SB) reported four cases of extrajudicial killings, eight cases of military encampment in barrios and schools, the forcible evacuation of 2,423 individuals, and eight cases of illegal arrest and detention from February to November 2017.

- An International Solidarity Mission in 2018 said soldiers used five schools for operations and were encamped in 15 villages.

- Around 1,000 residents of Las Navas and Bobon towns fled homes and farms in September 2021 due to “indiscriminate aerial bombing and shelling.”

- The Northern Samar Small Farmers Association claimed the 803rd Infantry Brigade also prohibited residents in interior villages from farming for three months as it rounded up and forced the surrender of hundreds of farmers who were then “made to pose as local NPA militia or supporters.”

Roots of conflict

Duterte, in December 2018, created the NTF-ELCAC, throwing billions of pesos at the “whole-of-nation” approach.

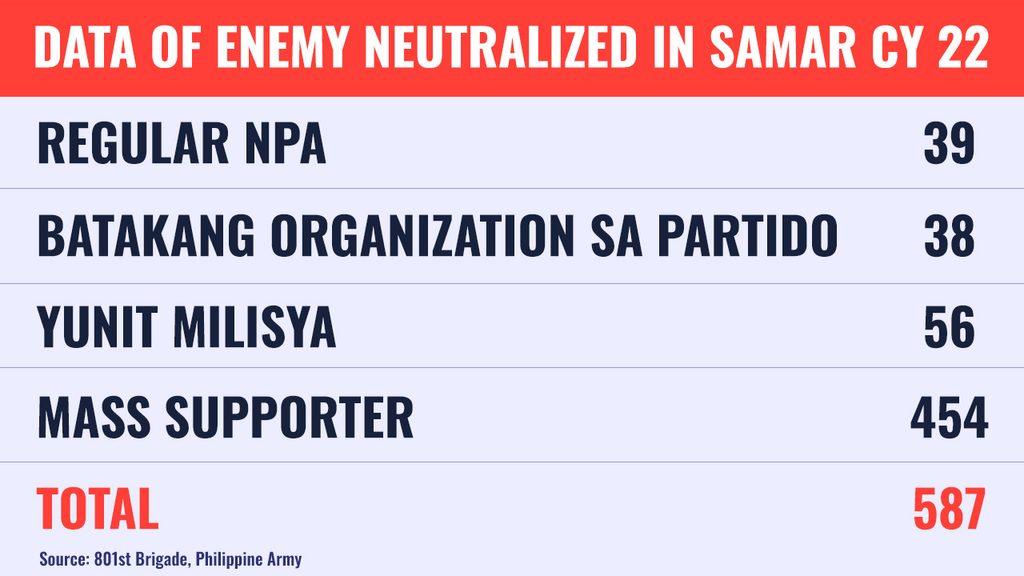

The AFP in Samar credits this for getting hundreds of rebels and their supporters to turn a new leaf. Human rights groups say the last category can be “artificial,” with locals sometimes tricked by orders to attend a mass meeting for aid, or coerced by hamletting.

Poverty is only half the equation of conflict on the island.

“Government neglect, political dynasties, and bad governance, fuel unrest,” UP Tacloban professor LadyLen Lim Mangada told Rappler.

A Commission on Human Rights-commissioned documentary for the Martial Law Chronicles Project graphically translates Mangada’s point, linking cases of razing of comunities, rape, torture, massacres and killings to inequality and big capital’s greed for timber and minerals.

The National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) 2017-2022 blueprint for Eastern Visayas said income inequality remained higher than the national average, with a Gini coefficient of 0.4649 compared to the national average of 0.4439. The Gini index measures income distribution across a population, with a higher index indicating greater inequality.

“Samar isn’t industrialized; we remain very backward in terms of livelihood,” Dory said. “Whatever the government’s propaganda about peace, if it doesn’t improve lives, people won’t believe; our former comrades won’t listen to us,” the former rebel said.

Half of the “whole-of-nation-approach” follows the dictum that rebellion is an offshoot of poverty, underdevelopment, and the lack of access to services.

NTF-ELCAC’s Barangay Development Program (BDP) gives “incentives” to local government units that cooperate in “clearing communities of ‘terrorists.’”

Centralizing billions of pesos under military supervision supposedly prevents development funds from going to rebel-friendly communities, “front organizations,” or corrupt local officials.

The flipside: barangay leaders who raise concepts like human rights and due process could find their faces pasted on trees, electric posts and fences and walls, together with other “terrorists.”

“The situation of militarization in far-flung farming villages in Samar is not reaching the media and the public,” Karapatan said in its 2021-2022 report.

Real needs

The task force in 2021 received a P16.4-billion budget for the BDP.

Northern Samar got P120 million for farm-to-market roads, water and sanitation systems, health stations, school buildings, electrification projects, and aid to poor families for the villages of Hitapian, Osang, and Nagoocan in Catubig; San Miguel in Las Navas; Quezon in Catarman; and Calantiao in Bobon.

In the first two weeks of September, engineers and staff of the provincial Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) office went around the Eastern Samar towns of Arteche, Jipapad, Can-avid, and Dolores to validate 25 proposed projects under the 2023 BDP.

These include farm-to-market roads, health stations, the construction and rehabilitation of potable water systems, renewable energy projects, and new primary school classrooms.

These barangays are cashing in the chips after being declared “insurgency free.”

But the effectiveness of NTF-ELCAC has been questioned.

Senators in November 2021 slashed its budget because of abuses and poor performance: It had completed only 26 of more than 2,000 projects. A bicameral compromise settled on a P17-billion budget, almost P4 million less than what it got in 2021.

As a result, in Eastern Samar and Northern Samar, the promised P20 million for some ”cleared” barangays went down to P4 million, Balangkayan town Mayor Allan Contado said in February.

What works?

Colonel Lito Pangatungan, deputy brigade commander of the 801st brigade, pointed out that civilian offices are still in charge of implementation.

“The three governors recognize that Samar Island should have complementing, reinforcing and united efforts in order to end the local communist armed conflict. Hence, they should frequently consult and openly coordinate and collaborate on this regard,” he told Rappler.

Samar’s dynasties were split in the last elections. The Tan clan in Samar province endorsed Marcos, while the Evardone family in Eastern Samar and the Ongchuan dynasty in Northern Samar backed then-vice president Leni Robredo.

But all three dynasties back the NTF-ELCAC and have promised “to harmonize and consolidate” their plans.

One-shot deals don’t work, Dory stressed.

In Villareal and elsewhere, initial “clearing” success wobbles because of the lack of capacity to sustain projects, he pointed out.

The new president, while campaigning in February, cautioned against making NTF-ELCAC the catch-all solution to insurgency.

“We will continue NTF-ELCAC but let’s not put all our hopes that it will solve all our problems because there are a lot of social problems that need to be addressed,” he said in an interview with the SMNI network.

In 32 of 39 “cleared” villages, the residents’ main concern is land distribution, decades after the passage of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law. It is an issue that cuts across the Philippine countryside, still a flash point for unrest.

There are many mechanisms in place to get a sense of what the grassroots really need. Yet year after year, LGUs complain that ruling dynasties, Malacañang, and power-tripping legislators have routinely shredded their list of urgent projects.

NTF-ELCAC’s BDF simply requires communities to get the task force’s nod for the same projects that grassroots units have been petitioning for decades. It is patronage coursed through the military instead of politicians.

Half a century of mailed-fist tactics that hinge aid to subjugation have failed to develop or bring peace to Samar.

“Military intervention will never solve decades-old skirmishes in Samar,” said Professor Mangada. “Transparency and accountability should be real, not imaginary/selective. Basic services should be available and accessible in conflicted areas.”

“LGUs in conflict areas should be given more resources and embrace a communitarian approach using evidence-based planning/intervention,” without the burdens of an ideological paradigm or political loyalty. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] The CPP-NPA’s 3rd Rectification Movement is bad news to the peace process](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/tl-cpp-npa-peace-talk-rectification.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=366px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[WATCH] Dahas Project, the team that continues to count drug war victims](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/dahas-project-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=404px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[DOCUMENTARY] Our 15 kilometers: Small fishers fear losing municipal waters to big operators](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/our-15-kilometers-iuu-fishing-docu.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=279px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Pikon ang NTF-ELCAC matapos mabuking ang fake surrender](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/animated-fake-surenders-military-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=326px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Who’s fooling who?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/rodrigo-sara-duterte-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=167px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

![[EDITORIAL] Dapat makinig si Marcos kay UN special rapporteur Irene Khan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/animated-un-marcos-human-rights-elcac-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=327px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.