SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – At the tailend of November, allegedly after its community standards were violated, Facebook suspended several pages and accounts critical of the Duterte administration and the hero’s burial given to the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

The account of journalist Inday Espina-Varona was suspended earlier this week, ironically, after reaching out to the social network to raise some issues about online abuse. Facebook pages, The Philippine Daily and Silent No More were also subsequently suspended, allegedly after a “flurry of reports” against them on the social media platform.

Other lesser known accounts were also reportedly taken down, only to be granted access again.

The series of suspensions in a span of one week raised concerns among netizens about security online. They also sparked discussions on the right to free speech and the reliability of Facebook’s moderation system.

It didn’t take long for word to spread that Oplan TokHang, an important component of the government’s war against drugs, had reached online spaces in the form of “Oplan Cyber Tokhang”.

Declaration of war

The term was coined by a group of netizens who called themselves “Duterte Cyber Warriors”.

On October 31, the Manila Times published a story entitled, “Senators declare war on ‘trolls’” which said that Senators Paolo Benigno “Bam” Aquino and Leila de Lima had called for concrete actions against fake accounts and the spread of manufactured news on social media.

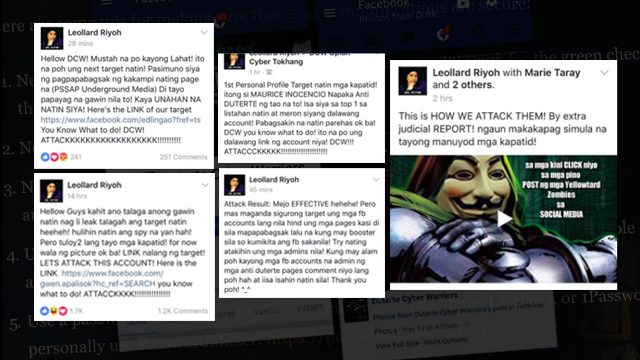

One of President Rodrigo Duterte’s staunch supporters on social media, Leollard Riyoh, also known as Mr Riyoh on Facebook, eventually released a video declaring a social media war against the “Yellow Army”, a derogatory reference to supporters of the Liberal Party, of which both Aquino and De Lima are members.

“Kung digmaan talaga ang gusto ng mga ‘yellow garbage,’ sige, lubus-lubusin na natin,” he said in the video. (If it’s really war that the “yellow garbage” wants, then let’s go all out.)

In the video, Riyoh anointed active supporters of President Duterte on social media as “Duterte Cyber Warriors” and invited them to join a private group called Duterte Cyber Warriors-Oplan Cyber Tokhang, where they would discuss their “missions” online. IT experts and programmers meanwhile, were invited to join their special operations, headed by the anonymous Salim Mcdoom, touted by the warriors as a hacker and a tech expert.

We were able to join the said private group, which was created on November 2. It had 3 administrators: Riyoh, Salim Mcdoom, and a certain Marie Taray.

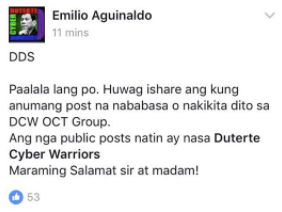

Members of the group were initially strictly filtered; fake accounts were blocked. The group had as many as 20,000 members. The administrators repeatedly advised their members to refrain from sharing their private discussions in more public fora.

‘Oplan Cyber Tokhang’

“TokHang” or Tukhang is an operation first introduced in Davao, where cops knocked on the doors of suspected drug users and dealers to persuade them to stop using or peddling drugs. “TokHang” is a contraction of Visayan words “toktok” (knock) and “hangyo” (request) and is now a popular term in Duterte’s war on drugs.

Oplan Cyber Tokhang, meanwhile, is two-pronged: its main purpose is to “attack” those who are “spreading false information” online by reporting them en masse or what they termed as “mass reporting”, while the second purpose is “special ops” – hacking and social engineering.

Later the group admitted that rumors about them “hacking” detractors were not true and were intentionally spread by them to incite fear.

For this report, we will focus on Oplan Cyber Tokhang’s first component: “mass reporting”.

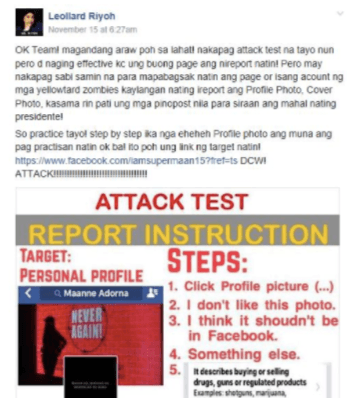

In the group’s first two weeks, Riyoh led what he called “attack tests”. His first targets were the Madam Claudia Facebook page and Maane Adorna’s Facebook account, both of which are critical of the Duterte administration and the Marcoses.

These tests failed, according to Riyoh himself, with only 800 out of the 20,000 reporting their targets. According to Maane, however, she was locked out of her account several times and was warned by Facebook about posts that violated their community standards.

At the same time, Duterte Cyber Warriors, on their public Facebook page and inside their private group, actively crowdsourced for names of accounts and pages that were “spreading false information” against the government.

‘Extrajudicial reporting’

Riyoh eventually published a video that gave more detailed instructions and explanations of Oplan Cyber Tokhang. According to the video they released within the private group, their goal was simple: to make “attacks” more potent by making sure that all “cyber warriors” attack one account at a time, a strategy he referred to as “extrajudicial reporting”.

The most effective way to have a Facebook account or page taken down, according to Riyoh, was to first report the profile photo, the cover photo, and their posts as “describing buying or selling drugs, guns or regulated products” before reporting the actual page to Facebook. The online army was also asked to wait for Riyoh and his co-admins to announce their targets and to await cues for their attacks.

Their tone was consistent: The President needs help; they are in a war.

As of this writing, the group had already organized attacks against The Philippine Daily Facebook page, and the accounts of Maurice Inocencio and television anchor Ed Lingao. The Philippine Daily reported being taken down by Facebook thrice. The accounts of the page’s administrators have also reportedly been suspended.

Several reports of Facebook users being logged out of their accounts on social media also made their rounds on Facebook, spreading fear that their accounts may have been compromised. In an email to Rappler, however, a Facebook spokesperson dismissed these incidents as a “bug in complex automated systems” they’ve deployed to protect users against malware and phishing.

The group was eventually taken down by Facebook on Tuesday night, November 29, when word of their discussions spread. Riyoh eventually claimed that the “leak” was intentional and that they let the spies in to scare people online.

Hit and miss

Does “mass reporting” work?

Facebook says that the number of reports on a particular post “does not impact whether [or not] something will be removed” and that it does not remove content “simply because it has been reported a number of times.”

Flagged content all go to a team of reviewers who will decide whether or not they violate Facebook’s community standards, including: hate speech, violence and graphic content, nudity, bullying and harassment, direct threats, attacks on public figures, and criminal activity, among others.

But while there is still no conclusive evidence that this kind of attack online is effective, Facebook’s content moderation policy has long been criticized for its inconsistencies.

For example, an American media organization, NPR, recently published an investigative report questioning how Facebook reviews flagged content.

NPR spoke with current and former Facebook employees on record and on background on how Facebook censors and reviews content.

According to former Facebook employees, flagged content go to a division called the “community operations team.” Facebook, however, eventually started outsourcing the task of reviewing content to consulting firm Accenture.

NPR’s sources revealed that this team of content reviewers has grown to several thousand people, with some of their largest offices being based in Manila and Warsaw.

The sources added that these subcontractors are evaluated in terms of speed, and therefore have to make decisions very fast – even as fast as one decision every 10 seconds.

NPR pointed out that this kind of workflow doesn’t allow reviewers to carefully go through flagged posts. While most content is simple enough to categorize and censor, others require nuanced analysis and thorough contextual review. If their sources’ claims are true, then this workflow is prone to mistakes and inconsistencies.

‘Mistakes do happen’

Oplan Cyber Tokhang essentially aims to take advantage of these inconsistencies. By submitting thousands of reports to Facebook at the same time, these online warriors hope to take down their detractors online using a hit and miss strategy.

In a report by Interaksyon, Pierre Tito Galla, who belongs to cybersecurity watchdog group Democracy.Net.PH, also explained how this can be effective.

“If I gather a thousand or maybe a hundred people, and maybe persuade them to report this person as spam or abusive or violating some community standards at the same time, then it may flood the Facebook reporting mechanism,” Galla said. “When that happens, it is very likely that through an automated means the account may be taken down.”

A good example of Facebook mistakenly taking down a post was when Facebook took down Lingao‘s post critical of plans to allow the burial of dictator Ferdinand Marcos at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. Facebook eventually admitted that the “post was incorrectly removed.”

“When we have millions of reports to review each week, mistakes do happen,” Facebook admitted in a statement.

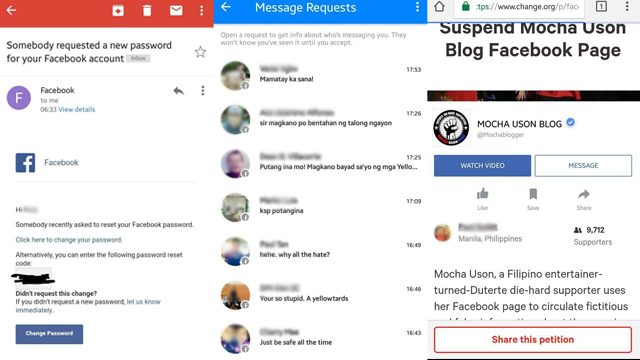

In October meanwhile, the creator of a petition on Change.org calling for the blog of celebrity Mocha Uson to be suspended on Facebook found himself, ironically, locked out of his account for 24 hours for posting “sexually explicit content.”

The photos reported however, were far from sexual. Instead, they were all screenshots of threats sent to him, his petition, and a Facebook notification that somebody sent a password change request.

Paul Quilet, who initiated the petition, said he sought an explanation from Facebook but to no avail. “I know someone’s responsible for the systematic social media account suspension that’s happening,” Quilet told Rappler.

The suspension of Varona’s account is another interesting case. Varona said in a post that Elizabeth Hernandez, Facebook’s head of public policy in the Asia Pacific, explained to her that “her account was incorrectly enrolled in a fake name checkpoint.”

But this explanation poses more questions about the way Facebook goes through these reports, as Varona had a verified Facebook account.

This feature, which is granted only to those whom Facebook considers as “public figures”, is supposed to let people know that a certain account is authentic. It is supposed to prevent people from being duped by fake accounts. How can a verified Facebook profile be mistaken by their moderators as a fake account?

This, and the information that a big chunk of these human reviewers are based in the Philippines, raises concerns about the reliability and objectivity of Facebook’s reviews. Critics argue: What if, for example, a report ends up in the hands of a moderator with a political agenda?

Inquirer.net’s social media editor Dennis Maliwanag, in a Facebook post, said that giving local BPOs the task of reviewing flagged content is not a good idea at a time when the country is severely polarized.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea that the BPO handling complaints of community standards violations is based in the Philippines. The country today is severely polarized. With several questionable suspensions of legitimate accounts, journalists and civil society members are beginning to wonder how objective are the reviews of complaints being carried out,” he wrote.

With Facebook being secretive about the way they review flagged content, evidence to prove the potency of these recent attacks are hard to come by.

But if Oplan Cyber Tokhang has made one thing clear, it’s that Facebook can no longer ignore the fact that there are continuous and organized attempts to game its system, and these are working, to some extent. And unless they do something about this, Facebook will never be as free from censorship and bias as executives claim it to be. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.