SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – A week-long case study captured by Rappler shows how information operations turn a potential disaster for the Philippine government’s handling of the Southeast Asian Games (SEA Games) 2019 into a win, successfully manipulating public opinion and isolating “mainstream media.” This doesn’t just shoot the messengers, it aims to cripple and mute them.

It’s a playbook of the kind of systematic and sustained attack traditional journalists and news groups in the Philippines have been subjected to in the past 3 years. Enabled by social media platforms, it leaves journalists and news groups vulnerable to repeated attacks that incite anger and hate, providing cover for potentially corrupt or blatantly incompetent acts of government officials that resulted in logistical blunders, insufficient food for delegates, and workers racing to finish the construction of venues. (READ: ‘Multi-billion SEA Games 2019 fund follows Cayetano where he goes‘ )

In a country called “the petri dish” by Cambridge Analytica whistle-blower Christopher Wylie and “Patient Zero” by Facebook, a lie told a million times becomes fact, with disinformation cemented top down when government officials joined the online smear campaign. (READ: ‘Fact or fiction? Memes attack media’s reporting on SEA Games 2019‘ )

Here’s how it happened.

How media covered the event

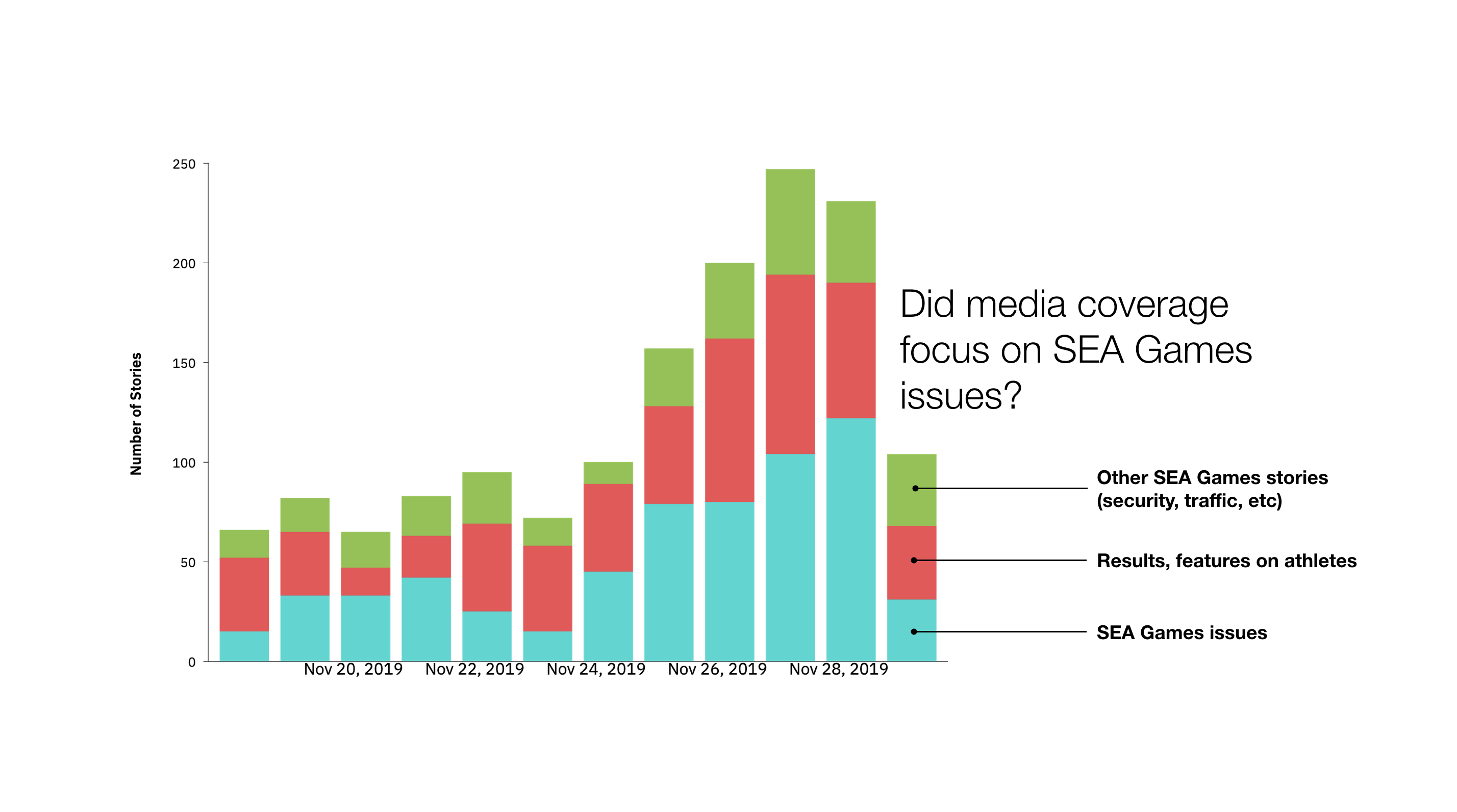

Rappler looked at 1,502 stories published about the SEA Games from November 18 to November 29, 2019, and using natural language processing, clustered each story by topics to see the main themes reported by news organizations as controversies erupted.

(Click and drag slider to move between slides)

We found 3 main clusters for the media coverage of the event: features and news on athletes and events, reports on the issues surrounding the SEA Games, and other related reports such as traffic advisories and security plans.

Contrary to allegations of organizers, politicians, and their supporters that the media was “only covering bad news” about the SEA Games, news organizations have, in fact, been consistently publishing stories about the athletes and the event itself before and during the peak of controversy. The media produced inspiring features and updates on the sporting event.

There has been, however, wide coverage of the issues related to the SEA Games as early as November 18, with Senator Franklin Drilon grilling organizers about the budget. Particularly hot at the onset of the controversy was news about the P50-million cauldron built in New Clark City.

More issues erupted on November 24 onwards, however, as the first wave of foreign athletes arrived, and reports of insufficient accommodation and food made the rounds on social media. This was followed by reports of still unfinished venues, unavailability of halal food for Muslim delegates, and complaints from foreign delegations, as reported by foreign media themselves.

Shifting narrative

Up to this point, conversations on the SEA Games were driven mainly by news organizations, as people reacted to reports about anomalies and logistical blunders.

“#Seagames2019Fail” started trending on November 25 all the way to the next day, with netizens calling out the government and organizers for the embarrassing welcome of competing athletes and allegations of corruption.

Phisgoc chair and current Speaker Alan Peter Cayetano initially responded to the flak by blaming delays in the Senate approval of the SEA Games budget, singling out Drilon on November 26 for proposing a cut in the SEA Games budget “by 33%.”

The following day, defenders of the Games and its organizers started going on the offensive against critics and the media.

In a privilege speech, Kabayan Representative Ron Salo railed against them for spreading misinformation. On the same day, Phisgoc chief operating officer Ramon Suzara called out the media for their “continuously negative reporting” of the event. Suzara then requested the media to publish positive reports and project the country in a good light.

Cayetano and Salo then amped up narratives against critics of the SEA Games, decrying, without presenting evidence, a supposed smear campaign against the event and its organizers. Cayetano said that some members of the media “admitted that there is overflowing cash to destroy SEAG.”

In an interview with ANC Early Edition meanwhile, Salo said there are “organized inauthentic behavior” online that aims to smear the games, and warned that people behind them may be charged with sedition.

Local and foreign journalists decried these “unacceptable” narratives and “sweeping accusations” against the media. (Read: Don’t blame media for SEA Games woes – NUJP and FOCAP hits SEA Games organizers for blaming media over mishaps)

This anti-media rhetoric was echoed and amplified by government supporters online as soon as it was unleashed. In just a day, narratives about the Games made a quick turnaround.

By November 27, #Seagames2019NotAFailure and #WeWinAsOne took over as top trending hashtags, highlighting two of the government supporters’ main narratives: that mainstream media is out to smear the Games, and that, for love of country, Filipinos should focus on supporting the athletes and spreading good news.

Managing a PR crisis

As soon as the organizers of the SEA Games started their offensive against critics, Rappler’s Sharktank, which continuously monitors activities within the government’s propaganda machinery, saw increased activity among the administrations’ network of propagandists and supporters on Facebook. Hover over the nodes below to see who they are:

The network map above shows how accounts within the propaganda network suddenly became more engaged at the peak of the PR crisis and after Cayetano’s first public statement on the issues were reported. Each node represents a page, profile, or website, and a connection is made when a node shares content made by another node in the map. Each node is sized according to the total engagement they generated during the scrape period. The bigger the node, the greater engagement generated.

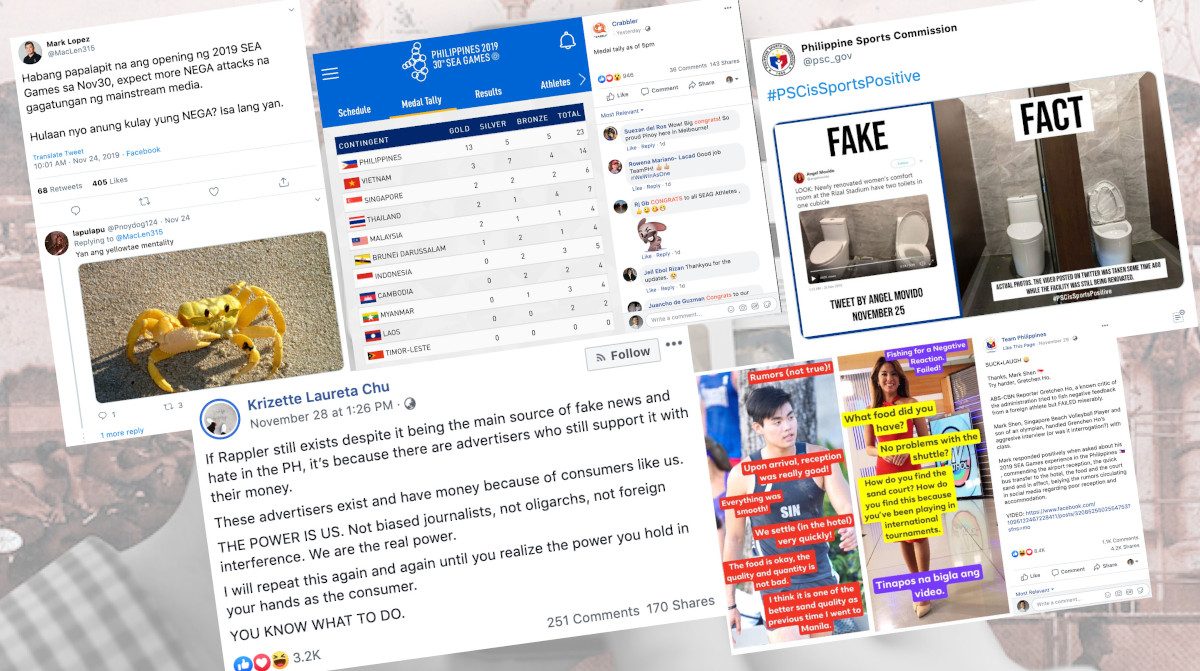

Pages like CrabblerPH, MochaUsonBlog, and DuterteToday – all known propaganda pages for the Duterte administration, had been actively amplifying content supporting the SEA Games and attacking news organizations. Propagandist-bloggers like Krizette Laureta Chu and Mark Lopez were among the most active content creators at the peak of the crisis, while Darwin Cañete, a controversial city fiscal or prosecutor who once likened critics of the Duterte administration to cockroaches, had been actively amplifying posts from the network to his 65,000-strong following on Facebook. Together, the 3 were able to generate 107,690 interactions in one day.

Zooming out on Facebook shows the government’s propaganda network dwarfing other networks and taking over the conversation through sheer volume. The network map below shows Facebook pages, groups, and accounts (within groups) that were part of the conversation on the SEA Games from November 18 to 29. Each node represents a Facebook group, page, profile or a website.

“Linkers” are groups or pages that spread posts through their network, while the rest are content creators who create and set the narratives being amplified. Connections are made when a node shares content made by another node. Nodes are sized according to the number of times content by a page or website was amplified – by either sharing or reposting – by another Facebook group or page.

(Click and drag slider to move between slides)

Notice that news organizations are at the center of the conversation, as they are amplified by pages and groups against the administration, all while receiving the brunt of attacks from the propaganda network.

At its peak on November 26, the propaganda network within Rappler’s database posted 1,057 times, generating more than 1.1 million total engagement on Facebook in one day.

Attacking the media

The narrative pushed out by the propaganda network focused on countering criticisms of the government and the SEA Games with attacks against the media, which, they claimed, have been spreading “fake news” in an effort to discredit the administration.

The topic cluster below shows conversations on Twitter, clustered by topics through natural language processing. Spread out across the map and in response to other clusters, were tweets that attacked the media, accusing them of reporting only bad things about the SEA Games and spreading “fake news”, essentially echoing narratives by Cayetano and other personalities involved with the sports event.

Just like on Facebook, the bulk of these tweets attacking the media peaked on November 27, when organizers and influential supporters of the Games also started publicly attacking the media for their coverage.

While #Seagames2019fail didn’t gain as much traction as #WeWinAsOne, it was viral enough to cause confusion on social media and discredit media reports on related issues.

This happened while the government and its supporters campaigned to divert attention and shift focus on the “good news,” equating being critical to being unpatriotic – an already all too familiar strategy in the propaganda network’s playbook. – with Akira Medina and Ranzhel Aganan/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newspoint] Fake press, undeserved freedom](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/newspoint-fake-press-undeserved-freedom-April-5-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINYON] Takoyaki tattoo at ang business model ng pang-iinis](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/20240410-Takoyaki-tattoo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.