SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE

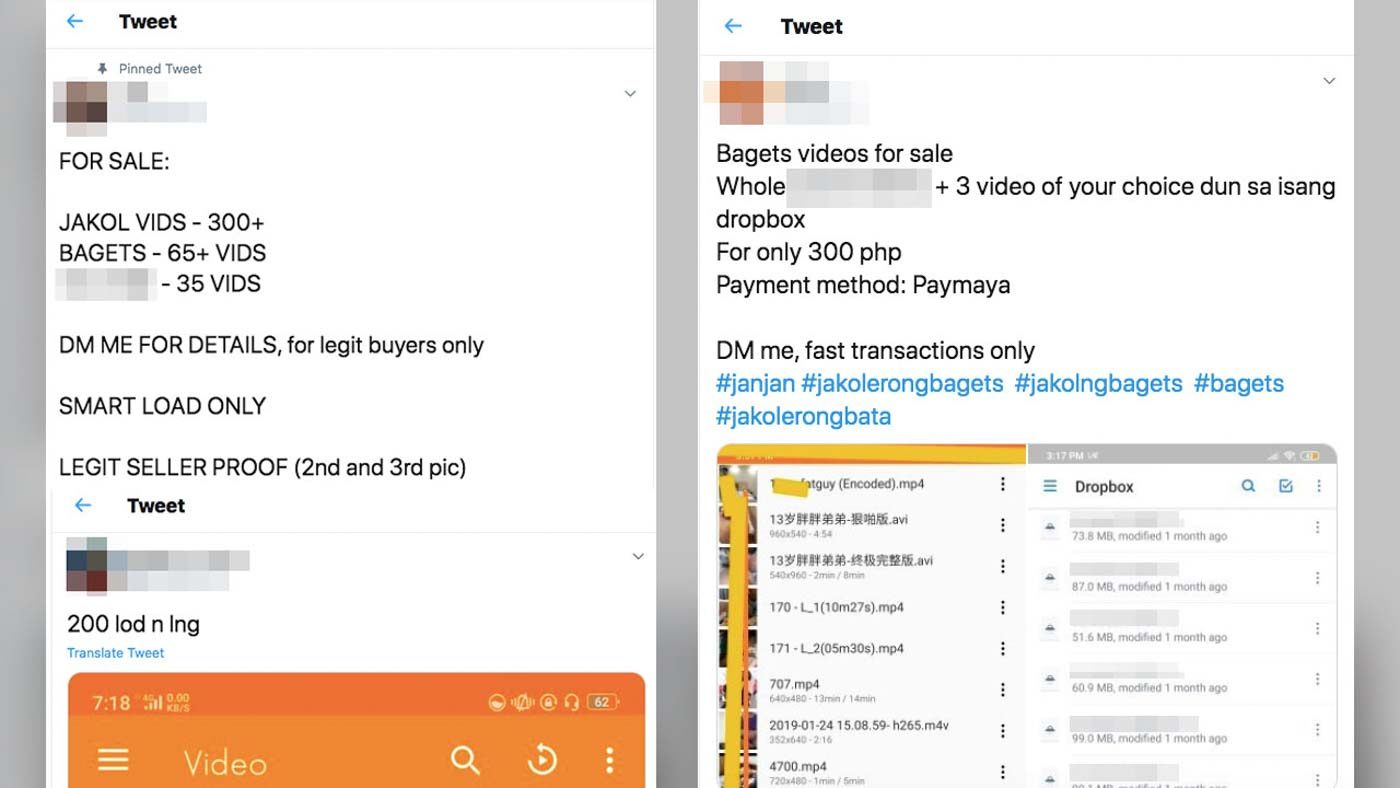

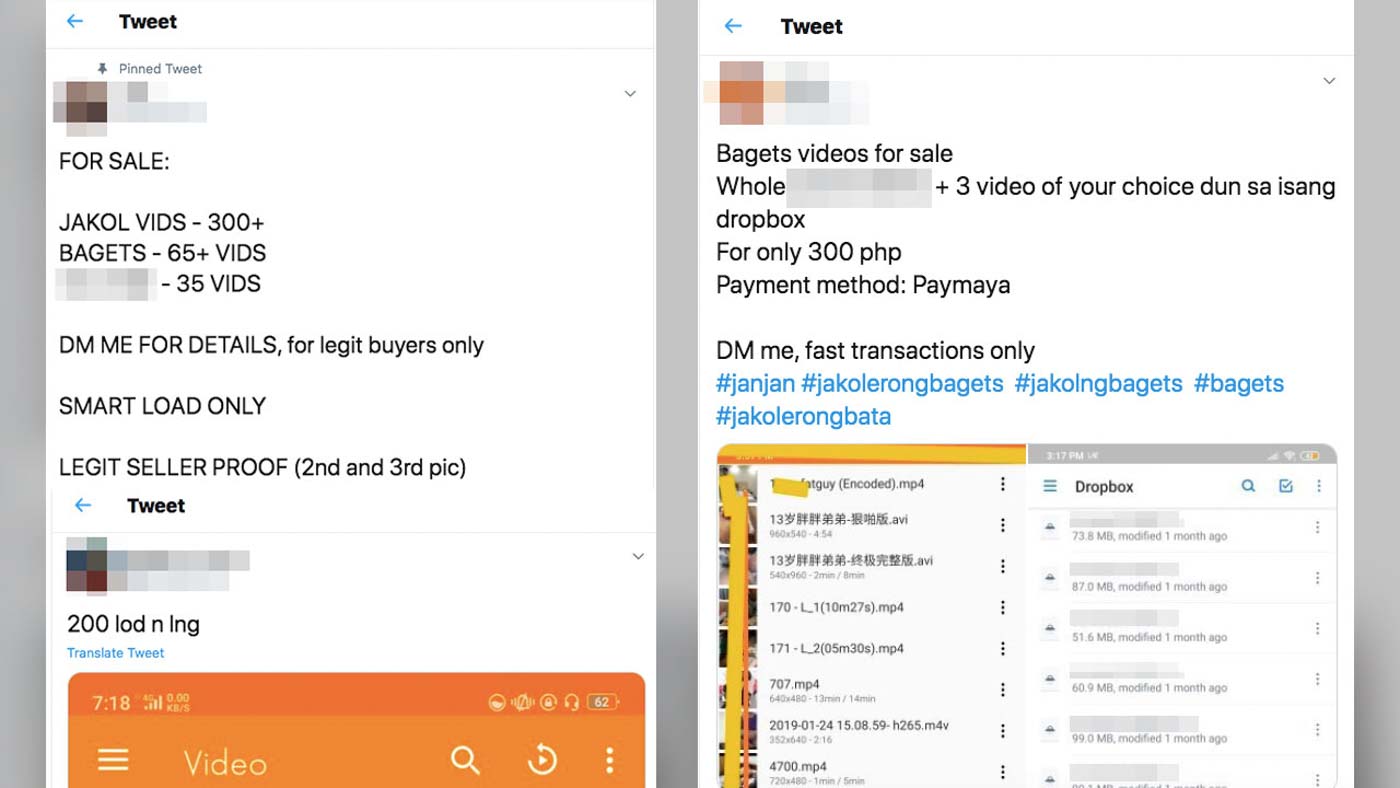

- From Part 1: Twitter accounts sell private sex videos without the owners’ consent for P300 to P500, even as high as P1,000.

- There are also Twitter accounts that sell and trade material of child sexual abuse, or videos of minors engaging in sexual activities.

- These videos are being sold for as low as P100 to as high as P500.

- Twitter says it has a zero tolerance policy for child sexual exploitation while the Philippine National Police’s Women and Children Protection Center vow to continue tracking perpetrators despite challenges.

CONCLUSION

READ PART 1 | Alter Twitter’s awful side: Leaked private sex videos for sale

MANILA, Philippines (UPDATED) – A boy stares into the camera. The phone’s yellow flash illuminates his face, highlighting features that suggest he is barely in his teens.

He is in a pitch dark room, sitting on what looks like a plastic bench. The camera points downward, revealing the boy naked from his waist down. At the 20-second mark, a hand moves into the frame and starts touching the boy’s private parts.

The video cuts abruptly. The sneak peek is up. To watch the entire video, you’d need to pay P300, says the tweet.

Videos featuring minors now exist alongside leaked private sex videos of young adults on social media, particularly on Twitter, where anonymous accounts troop to sell illegally recorded material.

Accessing child sexual abuse material has gone from the obscurity of the dark web into free and widely-used social media platforms.

On Twitter, videos of minors are referred to by a variety of terms and hashtags. The most common one is “bagets,” the colloquial name for young people.

In some cases, they are tagged as “Kiddie Meals” or even “SHS” for senior high school students. Some accounts post screenshots of videos featuring minors wearing their uniforms, with their private parts exposed.

Rappler found at least 8 accounts on Twitter selling and trading child sexual abuse material, or highly sexualized photos and videos of minors as young as 11 years old.

These accounts use hashtags that describe the nature of the acts in the videos to entice potential buyers. One describes the act of masturbating a minor, another explicitly paints a picture of boys having sex together.

One account that Rappler found sells a library full of child sexual abuse material for only P100 ($1.97). Another can be accessed for P200 ($3.95) or as high as P500 ($9.87).

A screenshot posted to perhaps promote a “collection” shows thumbnails of naked minors, all boys, engaging in various sexual acts.

One of them shows a young boy at the receiving end of oral sex in a cubicle inside a public restroom. Another shows a boy sitting in a living room, being masturbated by someone out of the frame. The boys grimace, as if they were not enjoying what was being done to them.

Many of the screenshots show minors masturbating inside their bedrooms, in their own private spaces, not meant for public consumption.

Experiences for sale

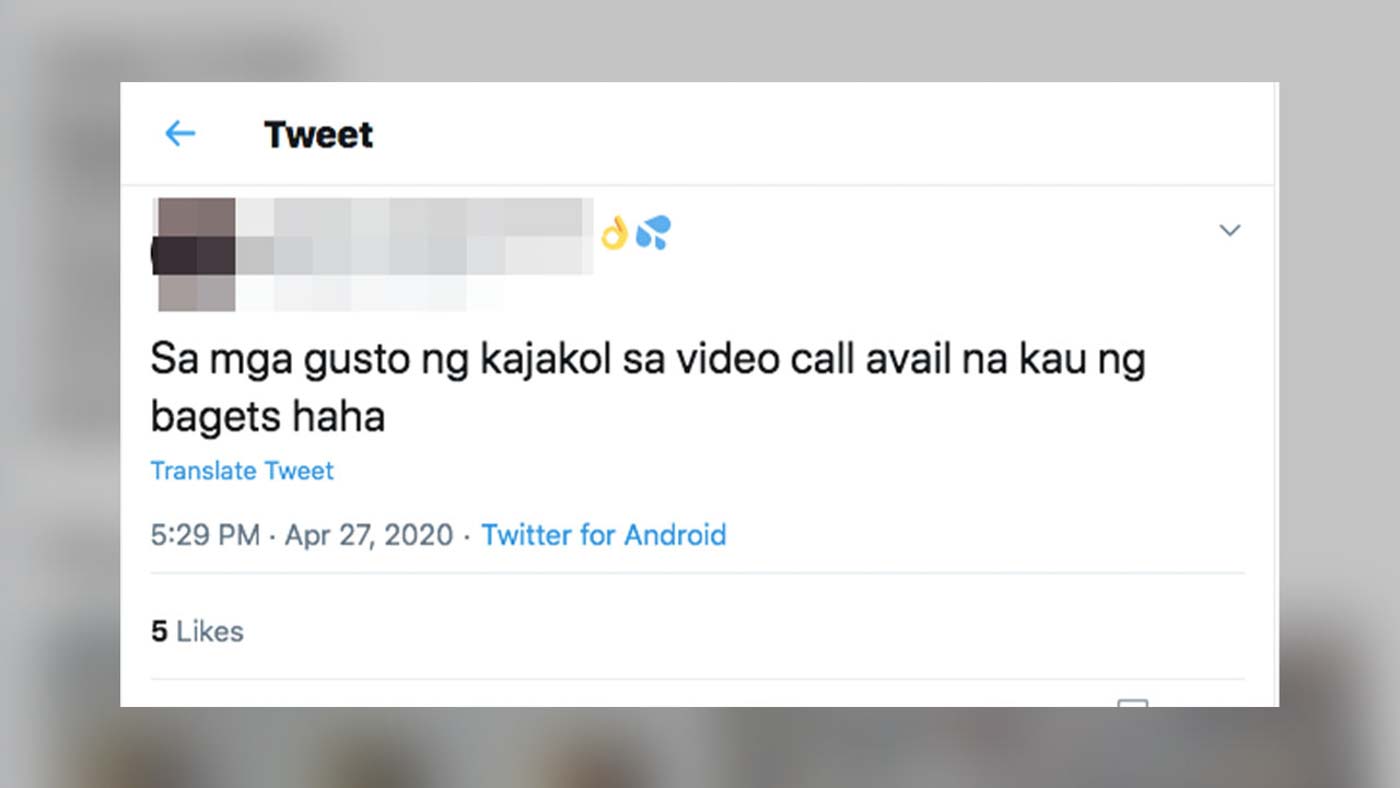

The sale of child sexual abuse material does not end here. There are also Twitter accounts that openly sell “an experience” with minors.

One account, with 1,485 followers, pimps young men in tweets. In one post, the account owner announced he was temporarily suspending his operations in light of the pandemic lockdown.

“Safety first,” the account said.

Days after, it was back in business looking for clients, selling the chance of engaging in cybersex with minors. It is unclear whether these children are forced to, or voluntarily, enter the trade, but the account serves as a middleman between clients and minors.

According to tweets, people wanting to engage in cybersex with minors just need to send a private message to the account that then facilitates the transaction. These are done usually through Facebook video calls or other messaging applications with video functionality.

Production, distribution, and possession of material showing children “engaged or involved in real or simulated explicit sexual activities” are illegal under Republic Act No. 9775 or the Anti-Child Pornography Act of 2009.

This law, however, has not stopped perpetrators from committing these crimes.

The sale of explicit videos of minors on social media platforms adds to the already huge problem of child sexual exploitation in the Philippines. This includes incidents of adults forcing children to engage in sexual acts through videocalls with clients who are mostly based abroad.

Exploitation of children

The extent of this type of exploitation in the country remains to be seen, according to Sheila Estabillo, who heads the Plan International Philippines’ Cyber Safe Spaces Project.

“Even though there is commendable progress in tackling child sexual exploitation in the country…there have been nonetheless only limited attempts to document and measure the exploitation of children,” she told Rappler.

Factors that lead to the rise of child exploitation incidents in the country usually include poverty and technological advancements that limit parental monitoring of internet activities, among others.

But Estabillo said that they’ve already come across victims who engaged in the sex trade voluntarity “not only to meet the basic needs and provide for one’s family, but to purchase wants, explore their sexuality, and have a sense of belonging.”

Plan International Philippines has pushed for a deeper understanding of the risks that come with the wide use of social media and the internet, especially among children and parents.

Through its Cyber Safe Space Project, the organization already engaged 17,534 children and young adults and 129,177 parents through advocacy sessions and cybersafety educational activities.

“We are not stigmatizing the child, but highlighting the consequences and their vulnerabilities,” Establlio said.

Hands full but trying

Law enforcers have had their hands full dealing with perpetrators of these crimes, especially those engaging in the trade or production of child sexual abuse material.

The Philippine National Police’s Women and Children Protection Center (WCPC) said that it often gets reports regarding child sexual abuse material in the country from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC).

The NCMEC, based in the United States, requires ISPs in its jurisdiction to report child sexual abuse material monitored in their respective systems. In 2019, it received almost 17 million reports through its hotline.

WCPC, headed by Police Brigadier General Alessandro Abella, lamented that this level of proactive engagement with ISPs is something that remains a challenge in the Philippines.

In 2019, the Department of Social Welfare and Development also pointed out the non-compliance of ISPs when it comes to reporting websites that distribute child sexual abuse material.

Still, over the years, law enforcement agencies have conducted operations and filed cases against perpetrators across the country.

Data from the Department of Justice (DOJ)’s Office of Cybercrime shows that at least 51 cybercrime cases related to the Anti-Child Pornography Act of 2009 were filed from 2015 to 2019, with 33 cases for violation of the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 on child pornography.

At least 235 cases have been filed against individuals who violated the Anti-Photo and Video Voyeurism Act of 2009 since 2015. There is no readily available information on whether there have been any convictions.

The WCPC urges the public to report incidents of child sexual abuse to their office. They can do so by sending screenshots of the post or website and links to the PNP WCPC Facebook page.

Never-ending problem for victims

Aside from existing Philippine laws, social media platforms have their own set of rules that spell out what’s not allowed to be posted.

Sharing of videos and images that are sexual in nature, without the consent of the owner, is prohibited on Twitter. Any account found to violate these rules is often immediately suspended from the platform.

In a statement to Rappler, Twitter said that it also has “a zero tolerance policy for child sexual exploitation,” adding that it “remains steadfastly committed to preventing the sexual exploitation of minors everywhere.”

According to the latest Twitter Transparency Report, the social media platform suspended in 2019 at least 269,188 accounts globally. They were all found to have engaged in sexual exploitation.

Despite efforts to curb the rise of online selling and trading of sex videos, including mass reporting, these accounts still thrive, and in many cases, have a huge following on social media.

Playing cat-and-mouse with authorities has long been the reality in the fight against Twitter accounts that sell and trade these illegal videos. Once an account is removed from the site, a new one is created almost immediately.

Rico*, an active Twitter user, took it upon himself to report known accounts to the social media platform, but said owners usually just quickly create another one.

An account that was reported and taken down 4 times eventually just got back online using a newly-created account, highlighting the near futility of efforts.

Gary and John, meanwhile, said they diligently report to Twitter accounts that post their videos. They’ve also asked the help of their friends to mass report these accounts, thinking that this would fast-track the process.

But perpetrators unfortunately still find ways to continue their operations.

In fact, one of the Twitter accounts that sells both Gary’s and John’s videos already set up a channel on Telegram, a popular messaging platform, so clients can directly receive updates about suspensions on Twitter and details about his new accounts.

As of posting, the group already has at least 623 members, despite being created only on May 2.

Perhaps it is on Telegram where these accounts found the fix to the vulnerability on Twitter, where users can freely report their tweets.

John said reporting can only do so much, especially if the accounts already have a huge following and market that enable them to continue their illegal acts.

“Itutuloy pa rin niya iyong ginagawa niya, magtatayo siya ng bagong account, may bibili pa rin sa kanya,” John said. “Unless he’s made accountable for his actions, patuloy pa rin niyang gagawin iyon sa iba at marami pang magiging biktima.”

(He will continue with what he’s doing, he’ll still create new accounts, and people will still buy from him. Unless he’s made accountable for his actions, he will still have a lot of other victims.)

Until then, John and Gary will have to make do with reporting to Twitter, desperately hoping that each account taken down means a near-end to the ordeal and emotional stress that they and hundreds of other victims, including minors, have had to bear.

The ball is now in the court of social media platforms and internet service providers – working with law enforcement agencies – to find a way to make the internet a safer space for everyone. – Rappler.com

*Names have been changed to protect their privacy

If you encounter commercial sexual exploitation of children, Plan International Philippines recommends reporting to the following government agencies:

- Inter-agency Council Against Child Pornography

Website: www.iacacp.gov.ph/report-to-us-2/ - Philippine National Police’s Anti-Cybercrime Group

Hotlines (02) 722-0650 / 0917-847 5757

Email pnp.acg.angelnet@gmail.com - Inter-agency Council Against Trafficking

Hotlines 1343 in Manila, 021343 for those outside Manila

Email info@cfo.gov.ph

Website: www.1343actionline.ph - National Bureau of Investigation, Cybercrime Division

Hotlines (02) 523 8231 to 38 (local 3454, 3455)

Email ccd@nbi.gov.ph

The PNP’s Women and Children Protection Center can also be reached through Facebook or its hotline 0919 777 7377.

Tweets may also be reported through Twitter using this form.

Adults whose videos are being sold or spread without their consent may report to the NBI and PNP.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.