SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

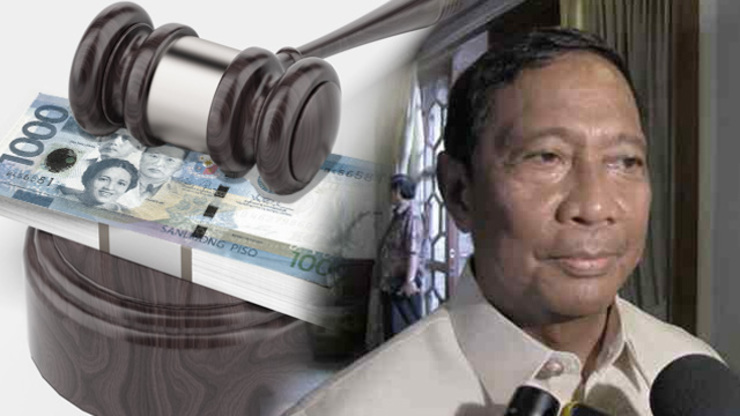

MANILA, Philippines – Sometime in 1991, while the first graft cases against Jejomar Binay were pending with the Ombudsman, aides of the Makati mayor visited Margarito Gervacio a number of times.

Gervacio was the prosecutor leading the panel investigating charges hounding Binay: rigged bidding and overpricing by P16 million of office partitions and furniture of the new Makati City Hall building, based on the findings of the Commission on Audit (COA).

Feliciano Bascon, former president of the Association of Barangay Captains, a Binay ally who would eventually fall out of grace, and Nelson Irasga, then city engineer, lobbied for the dismissal of the cases and delivered “cash gifts” to Gervacio. In return, they were assured that Gervacio would recommend the dismissal of the cases.

Two years later, in 1993, members of the Ombudsman’s investigating panel did just that: they found no probable cause to pursue the charges against Binay and recommended dropping the charges. Aniano Desierto, then special prosecutor, gave his go-signal.

Ombudsman Conrado Vasquez did not act on this and formed another panel to review the earlier findings. In 1994, the review panel did the opposite; it recommended filing of a case versus Binay with the Sandiganbayan. Vasquez immediately approved it.

When Desierto became Ombudsman in 1995, luck shone on Binay. Desierto withdrew the case in 2001 and the Sandiganbayan gave its nod.

Belated move

Bascon made the startling revelation of bribes given to lead prosecutor Gervacio, without giving specific amounts, in a sworn statement. But it came late in the day, in 2003, two years after the case had been pulled out.

We found Bascon’s affidavit in the archives of the Sandiganbayan, part of the piles of records on the graft cases against Binay that never prospered.

It was Bobby Brillante – who had consistently opposed Binay when he was councilor and vice mayor – who filed the first case in 1988. He submitted Bascon’s affidavit to Ombudsman Simeon Marcelo who apparently referred it to the Sandiganbayan. The intent of Brillantes and Bascon was to have Gervacio, who by that time had been promoted to Deputy Ombudsman, inhibit himself from investigating other cases against Binay.

Here are excerpts from the Bascon affidavit:

“…In the latter part of 1991, I, together with then City Engineer and Makati Building “…I was a close associate and confidante of Mayor Jejomar C. Binay [from 1988 to 1992] and as such, I was asked to perform sensitive and confidential tasks by the mayor.

“Official Nelson Irasga, visited Atty Gervacio on several occasions to lobby for the dismissal of the graft cases against us.

“In our visits to Atty Gervacio, we would deliver ‘cash gifts’ in return for his assurance that he would recommend the dismissal of the cases.”

Merits skirted

While alleged payoffs may be one factor in Binay’s winning streak, an apparent lack of prosecutorial zeal was another, caused perhaps by excessive workloads and mediocre skills of government prosecutors.

When Desierto stepped down as Ombudsman in 2002, he left a miserable legacy: conviction rate was a low 6%. His term was marred by an impeachment complaint filed in late 2001 by lawyer Ernesto Francisco who accused him of accepting a P500,000 bribe from his client. This came soon after Desierto withdrew the Binay case.

We found in our review of court records of 5 graft cases versus Binay filed with the Sandiganbayan that were either withdrawn or dismissed that, in most, there was hardly a discussion of their merits. They collapsed on grounds of procedure.

Binay’s lawyers stood on valid ground when they asserted that the Makati mayor’s right to speedy trial was violated. The first case took all of 13 years to resolve, from 1988 when it was filed till 2001 when it was withdrawn. On the average, lawyers we consulted said that cases should be resolved within 5 years.

Another case – on rigged bidding of office furniture and partitions in 2001 which led to an overprice of more than P9 million – was dismissed because of the frailty of the Information or the statement of facts that showed probable cause to merit pursuing the case.

Justice Godofredo Legazpi, who penned the decision on October 30, 2006, said: “…the Information is fatally defective…it failed to specifically allege the facts constituting the element of evident bad faith.”

This happened during the term of Ombudsman Merceditas Guiterrez.

Strong lobby?

Brillante, who filed this case, raised an uproar. He tracked down the timeline and found that the case was raffled on October 27, 2006, a Friday, and was quickly decided on October 30, a Monday. This was unusual in the annals of the Sandiganbayan.

Brillante issued a statement saying, among others, that he received information that Justice Diosdado Peralta, who was then with the Sandiganbayan (he is now a Supreme Court justice), lobbied for Binay. His sister, Vissia Marie Peralta-Aldon, was Binay’s personnel chief. Brillante also alleged payoffs to Justice Legazpi and his colleagues, Justices Efren de la Cruz and Norberto Geraldez.

The Sandiganbayan cited him for contempt. Brillante spent a month in detention.

On the single case that delved into the merits, involving overpricing of office furniture, the public never got to know the full story because Binay’s lawyers moved for a demurrer to evidence (akin to a motion to dismiss the case) since they found the evidence presented by the prosecution to be feeble. The Sandiganbayan decided in favor of Binay.

Justice Edilberto Sandoval wrote in April 7, 2011:

“The admission made in open court early on by the Prosecution that the Information they filed…does not conform with the evidence on record, foretold a bleak conclusion to this case.” He said that the Prosecution was unable “to prove the elements of the offense…”

Value of COA report

In the courtroom, COA reports are considered hearsay. However, they are important road maps that warn of danger signals. Legally, they do not meet the bar of proof beyond reasonable doubt thus they need to be bolstered by further evidence. Testimonies of witnesses are crucial. Here in come the investigative skills of the prosecutors.

Under President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, the Office of the Ombudsman was given new tools: access to income tax returns of officials under investigation as well as their bank accounts.

Meanwhile, former mayor Elenita Binay continues to face graft cases in the Sandiganbayan, based on COA reports on overpricing of equipment of Ospital ng Makati. With a new team at the Ombudsman and a much improved conviction rate, Dr Binay navigates a more difficult terrain. – Rappler.com

(“Gavel image” courtesy Shutterstock)

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.