SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

*Names have been changed to protect the survivors

Joy Anne* just wanted to see her son’s body.

It was August 26, 2016. At around 4 pm, cops from the Caloocan City police station stormed their home in one of the city’s poorest barangays. Their target was her son, Tisoy*, a tricycle driver.

That day, Tisoy was with three friends in their home. Police barged in and ordered them all out, one by one. The walls of their home were thin – a patch of wood and concrete that barely supported a staining roof.

As Tisoy stood up to leave, a policeman stopped him.

“What is your name?”

Tisoy gave his full name.

“You stay.”

Then, gunshots.

A minute later, the police dragged him out, left him splayed on the barangay’s roofless basketball court, and pointed to him.

“Ito, hard killer,” the policeman said. (This person is a hard killer.) Tisoy was already dead.

They then took him away.

Joy Anne only found out around an hour later as she walked home from work, facing her trembling daughter.

“Wala na si Kuya Tisoy,” her daughter told her. (Big brother Tisoy is gone.)

Joy Anne dropped her bag and ran. She ran aimlessly. She ran off to the highway. She turned to the corners. She thought she could run far enough, fast enough, to escape reality.

She found her way back to her daughter and they walked home.

Tisoy was no longer inside his room. There was only his blood – his pillow was soaked red, and bullet holes marked the walls. They must have forced his head onto the pillow before shooting him, she thought.

Joy Anne made her way to the funeral home, Northstar Funeral, along Zapote Road in Caloocan City.

There, she was asked to pay P35,000.

Milking the dead

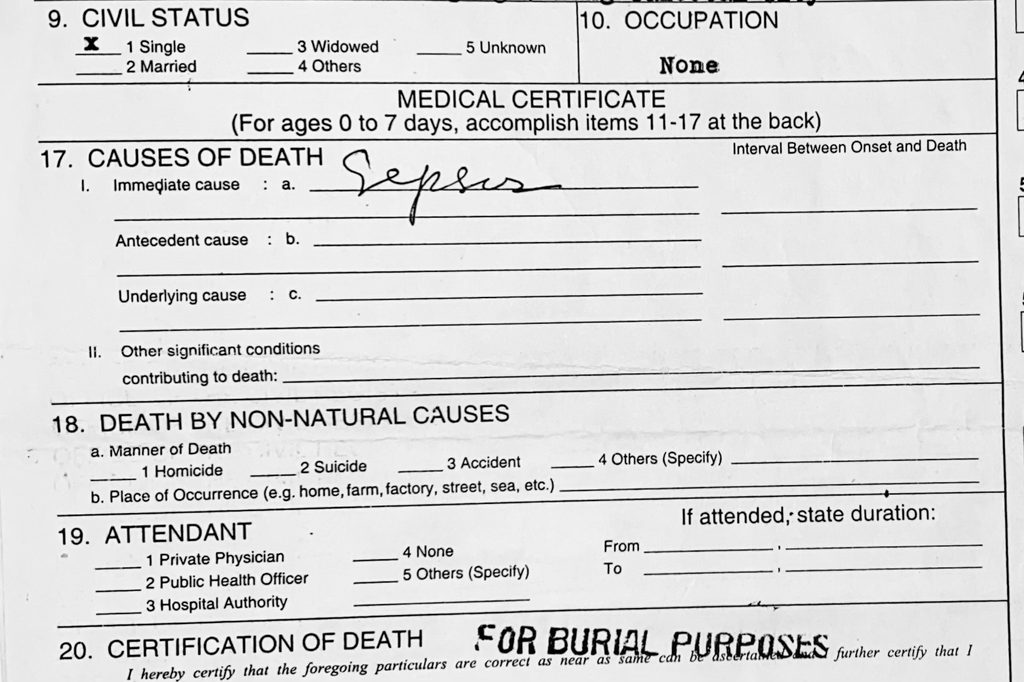

This was the computation: funeral service, P20,000; autopsy, P15,000.

“Pinatay ’nyo na nga ang anak ko, peperahan ’nyo pa kami?” Joy Anne told the funeral staffer, a woman whose name she never bothered to ask. (You already killed my son, now you’re still milking us dry.)

What else was there to examine, Joy Anne thought, in a body torn by bullets?

“Wala kang magagawa,” the staffer told her, before offering a proposition. (You can’t do anything about it.)

“If you don’t want him autopsied, we can put sepsis as the cause of death.”

Joy Anne knew it was not true. Sepsis is the body overreacting to an infection. She knew Tisoy was not taken by germs or viruses, he was killed by people.

But Joy Anne also knew the staffer was not mistaken: “I couldn’t do anything about it.”

Joy Anne had no stable job. She peddled bottles of herbal treatments and whitening lotions, earning P50 a piece sold. There were days she sold a dozen and there were days she sold none.

She had no one to turn to. Her family, just like her, was barely making a living. She could not even sell Tisoy’s tricycle. It was owned by someone else. Tisoy borrowed the tricycle in the evenings to ferry people who returned home late at night. Money came in trickles.

The woman gave Joy Anne a waiver to accept sepsis as Tisoy’s cause of death.

She signed it and, at dawn the next day, the funeral parlor delivered Tisoy’s body in a casket to their home.

During his wake, no one came to visit, not even the friends who were with him right before he was killed.

“Ang daming natatakot,” Joy Anne said. (A lot of people were afraid.)

Tisoy would be among the first victims of this apparent modus by funeral parlors, where they demanded higher payments from drug war victims before they properly processed their death certificates and indicated that the victims died of gunshot wounds. Others who could not pay were made to say their fathers or sons died of pneumonia.

The truth behind Tisoy

By policy, the Philippine National Police (PNP) investigates all incidents where its personnel use a gun to kill a suspect. Leading these probes is its Internal Affairs Service (IAS).

The IAS, however, can’t move forward if the family does not want them to probe into the killing. This was the case for Joy Anne. Since she knew policemen killed her son, she trusted no one.

She was called to the police station for her testimony. She didn’t show up.

“How can I participate in an investigation when all they do with my son is lie?” Joy Anne asked.

In these cases where the family refuses to cooperate in the internal probe, mostly driven by distrust and fear, the PNP IAS only gets the side of the police squad under investigation – it becomes a one-sided investigation and eventually languishes.

But Joy Anne still needed something from Tisoy’s killers. She wanted them to admit to killing her son. She wanted a police report.

So, after several months, Joy Anne showed up at the Caloocan City Police Station and asked how her son’s killers viewed events on August 26, 2016.

According to the police report, at around 3:40 pm, the desk of the Caloocan City Police Community Precinct 3 “received a telephone call from [a] confidential informant.”

The informant apparently told the desk officer “rampant illegal selling of prohibited drugs” was happening in one of Caloocan’s poorest barangays, pointing to the home of Tisoy.

Immediately, the Caloocan police formed a team, led by a certain Senior Inspector Bernard Pagaduan.

The police arrived at 4:15 pm and claimed they caught Tisoy in the act of selling drugs right outside his home. Three people were immediately arrested while Tisoy allegedly ran inside their home and shot at the police.

The police returned fire and killed him. The report identified the shooters as Police Officer 2 Jay Janno and Police Officer 3 Valderama, whose full name was not indicated.

Scene-of-the-crime operatives found a revolver with three unfired bullets, two sachets of methamphetamine (shabu), three cartridge cases, a bullet, and drug paraphernalia “used for sniffing shabu.”

In the last paragraph of the police report, police said they had Tisoy’s body autopsied.

“The cadaver of [Tisoy] was brought to the PNP Crime Laboratories (sic) for autopsy examination,” the report read.

Joy Anne was never informed about the autopsy and she was never given results of the examination.

How could the funeral parlor want to charge her P15,000 for an autopsy which the police had already supposedly done, she wondered.

But she found out about it belatedly. The police shared its report only in December 2020 – over four years since the killing. Northstar Funeral Homes closed in 2018, and all Caloocan policemen were all sacked from their posts in 2017, following a string of operations that killed minors.

Bernard Pagaduan, the commander of the team that killed Tisoy, has since been reassigned and promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in Bulacan, a known drug war killing hot spot north of Caloocan. As of January 13, 2022, Pagaduan was serving as the acting police chief of the municipality of Marilao.

Remembering Tisoy

Five years have passed since Tisoy was killed, among at least 7,000 drug suspects so far shot dead by policemen since Rodrigo Duterte became president in July 2016. Human rights groups placed the number of drug-related killings at a minimum 30,000 in 2019, to include those committed by vigilantes inspired by the President’s oft-repeated order to “kill, kill, kill.” The numbers may have risen by now.

Joy Anne had Tisoy’s remains exhumed from the Tala Cemetery in July 2021 after he faced eviction. Tisoy was cremated.

Tisoy’s ashes filled a ceramic urn, which Joy Anne placed inside a curtain-covered cabinet near their dining room. He was a few steps away from the room where the police killed him. Joy Anne prayed to his urn in the morning and at night.

“Hello, anak, good morning,” she would greet him. (Hello, my son, good morning.)

“Anak, ito, bantayan mo kami, matutulog na kami. Ikaw ang aming gabay,” she would whisper to him before sleeping. (My son, we are now about to sleep, please watch over us. You are our guide.)

“’Wag kang mag-alala, malapit na ang hustisya para sa ’yo,” she would add. (Don’t you worry, justice will be yours soon.)

She pulled Tisoy out of the cabinet slowly, careful not to drop him. The urn was heavy and cold to the touch. Even when it was spotless, Joy Anne wiped it with a towel.

“Inaamin ko, na-involve siya sa drugs dahil wala siya gaanong trabaho,” Joy Anne said. (I admit, he got involved in drugs because he did not have much work.)

Joy Anne wanted to be clear: Though he may have been involved, Tisoy did not buy, sell, or use drugs.

Tisoy let his friends use his room as a venue for their drug sessions. In exchange, he asked each of them to pay him P20 each time they came over. Joy Anne saw them come in. Tisoy did not join them in their sessions. But she knew his friends were also just coping.

Poverty led them all to drugs. Unfortunately, in Duterte’s Philippines, involvement in drugs could spell a death sentence.

“I raised him and they took his life just like that,” Joy Anne said, regret in her voice. It should be God who takes our lives, not them.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Dahas Project, the team that continues to count drug war victims](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/dahas-project-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=404px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.