SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

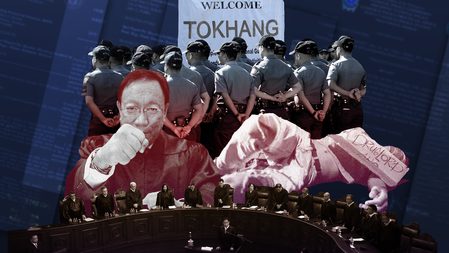

Editor’s Note: In this 3-part series, a Rappler investigative team scrutinized the first batch of files submitted in June 2018 by the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) to the Supreme Court. Consisting of police reports, the documents were supposed to provide insight into the regularity of police operations in President Rodrigo Duterte’s violent campaign against illegal drugs. Part 1 showed how the “rubbish” files submitted by the OSG served to stall the case at the SC, also indicating how this could build a case against the Duterte government before the International Criminal Court. Part 2 zeroes in on known hot spots that had well-publicized killings and points out what’s blatantly missing in at least the first batch of OSG submissions.

At a glance:

- Thousands of deaths in police anti-drug operations are not part of the first batch of files submitted by the Duterte government to the Supreme Court.

- Folders of killing hot spots like Bulacan in the first batch do not include files on a drug-related “nanlaban” (fought back) killing.

- A folder on Metro Manila is missing in the first batch despite well-documented drug-related deaths in the National Capital Region.

- The incomplete documents cast doubt on the legitimacy of the drug war, says the Commission on Human Rights. This also makes it practically impossible to exact accountability from abusive and erring cops.

On January 10, 2017, Alvin Ronald “Heart” de Chavez was found dead in San Jose, Navotas.

Close to midnight, masked men grabbed and dragged Heart out of her house after pounding her head on a table. She was nowhere to be found until neighbors told family members who were desperately looking for her that she was in an empty house where her lifeless body lay with a bullet in her cheek. More bullets pumped into her body left her dead.

The police report categorized her killing as a death under investigation (DUI) perpetuated by unknown assailants, commonly referred to as vigilantes. The De Chavez family, however, believes cops killed her.

Despite this case being extensively reported on by the media, the De Chavez killing in Navotas is not found in at least the first batch of files submitted by the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) to the Supreme Court (SC), where the constitutionality of the drug war is being questioned. The bloody crusade has been a centerpiece of President Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-crime campaign – among his promises when he ran in 2016.

The first submission made by the OSG led by Solicitor General Jose Calida covered 165,454 individual files of police reports. A careful examination of the documents showed that the bulk of files for Metro Manila were excluded despite the killings being concentrated in that region at least during the timeframe specified by the SC – from July 1, 2016, to November 27, 2017.

The only token Metro Manila files included in the first submission were those that pertained to the petitions filed by the Center for International Law (CenterLaw) and the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG). These covered 33 killings in San Andres Bukid, Manila, for CenterLaw, and one killing in Tondo and another killing in Quezon City for FLAG. (FLAG’s petition is based on 3 killings in Tondo, Quezon City, and Baguio.)

These files were separately organized under what Calida called “Category 2,” according to his own pleading to the SC submitted in November 2019, and were the only files the solicitor general was initially willing to give the petitioners.

The failure to submit all field reports from the National Capital Region meant that records of at least 1,640 killings were excluded from what was given to the SC. The count is a conservative estimate based on a tally by ABS-CBN News Online, which recorded killings across the country culled from police and media reports.

The police, as multiple investigations have found, have been underreporting killings to the public.

“Having complete documentation cannot be over-emphasized. Should there be basis to bring cases to court, these will only prosper with proper documentation. Without proper documentation, then operations are only matters of statistics,” said Ray Paolo Santiago, executive director of the Ateneo Human Rights Center.

A monthly recording of the drug war killings from July 2016 to November 2017 showed that they were frequent in the early months of Duterte’s term. He declared he would put an end to drugs and criminality within 6 months of his assumption of the presidency.

The recorded incidents dropped in January 2017, after the killing of South Korean businessman Jee Ick Joo. Jee was kidnapped then strangled to death by anti-drug policemen in Camp Crame, the national police headquarters, in October 2016.

The controversy pushed Duterte to suspend the drug war from January to March 2017. After the campaign was “reloaded,” the killings picked up again by April.

In Metro Manila, according to the ABS-CBN tally, they peaked at 237 in September 2016, and dipped to their lowest in November 2017, with only 6 on record. These figures, however, expectedly did not include all the killings that happened during the timeframe being tracked.

Human rights lawyer Jose Manuel “Chel” Diokno, chairperson of FLAG, said the only Metro Manila files he could recall from the first OSG submission were the files on the 33 killings in San Andres Bukid. These killings are the subject of the petition of the other group, CenterLaw.

Calida was at first willing to provide petitioners only the files on the deaths that concerned their petitions. He relented, but only after a motion for contempt was filed by CenterLaw with the High Court against the OSG.

Calida earlier said in his pleading to the SC that the Philippine National Police (PNP) misunderstood the directive of the Court. According to him, the Court had been using the term “Deaths Under Investigation (DUIs)” to refer to drug war killings when, for the police, DUIs meant all unresolved killings, drug-related or otherwise. That’s why there were so many non-drug related files in the submission.

Following Calida’s argument, deaths under investigation, irrespective of intent, should have included the De Chavez killing. Yet, it was not among the files in the first batch submitted to the SC.

Moreover, lumping all DUIs shows inadequate tracking of drug-related deaths and “reflects the attitude being put into really resolving the drug-related DUI cases,” said Santiago of the Ateneo Human Rights Center, which found in its own study that the earlier circulars of the drug war violated constitutional rights.

“There will be inadequate basis to say that everything is actually above board and vice versa,” he said. “There will be no accountability if ever there are cases that were done beyond the bounds of the law.”

Below is a 3-page collation of well-documented high-profile deaths in Metro Manila (Pasay City, Manila, Quezon City, Valenzuela City, and Caloocan City) that the OSG did not include in the first batch of folders it submitted.

The incidents reported in the media involved police operations that resulted in the deaths of suspected drug personalities. Police claimed the victims resisted arrest and fought back, justifying their use of violence as part of self-defense – an all too familiar narrative in Duterte’s war on drugs.

Of what use?

In the first batch of folders that CenterLaw examined covering 1,792 deaths, it found that 90% of the solved cases were not drug-related, while 55% of the unsolved cases were also not drug-related.

CenterLaw said the folders it analyzed covered killings in Metro Manila (the San Andres Bukid cases), Ilocos Region, Central Luzon, Southwestern Tagalog Region, Bicol, Central Visayas, Eastern Visayas, Zamboanga Peninsula, and the then-Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. CenterLaw did not specify which regions accounted for the 90% non-drug-related solved cases and the 55% non-drug related unsolved cases.

Rappler’s separate and independent scrutiny of 165,454 files in 291 folders revealed that most of the files were useless in determining whether police operations related to the drug war were above board. While the bulk of the files for Metro Manila were missing, there were folders on other known killing hot spots: Bulacan north of Manila and Negros Occidental in the Visayas.

Negros Occidental is where killings – both drug-related and politically-motivated – have risen over the years, particularly since 2016. Negros Oriental and Negros Occidental comprise Negros Island, which has long been plagued by violence. (MAP: Negros killings since July 2016)

Bulacan is one of the 7 provinces that comprise Central Luzon, the region tagged as one of the killing fields in Duterte’s drug war. A province of over 3 million people, Bulacan is the most populous in Central Luzon and the 3rd most populous in the entire Philippines, following Cebu and Cavite.

After a deluge of drug-related killings in Metro Manila in 2016 and 2017, the epicenter shifted to Central Luzon, with Bulacan accounting for the highest number of these killings. The shift also coincided with the assignment of Metro Manila policemen to Central Luzon, including Bulacan. (READ: Central Luzon: New killing fields in Duterte’s drug war)

We looked closely at the Bulacan folders and saw that, out of the 557 killings on file, only 352 were drug-related. None of the files involved deaths in police operations, however, even though the widely-reported anti-drug big sweep in 2017 fell well within the SC’s time frame.

Within a period of 24 hours, Bulacan police killed 32 in a one-time-big-time operation from midnight of August 15 to midnight of August 16, 2017. The names of the dead in that big sweep, documented and reported, do not appear in the folders submitted by the OSG to the Supreme Court.

The OSG had to submit a second batch in November 2019 after petitioners asked the High Court to hold the office in contempt. When asked about the second OSG submission, Diokno told Rappler on February 17 that “there was no relevant data that we could extract from the second batch,” adding that “there were a lot of irrelevant material.” The description was no different from observations on the first submission.

In a pleading in February 2020, CenterLaw said the same of the second submission: “On November 29, 2019, after the stonewalling machinations, respondents furnished the petitioners the documents purportedly in compliance with the directives of the Honorable Court. It turns out, however, that the documents indeed included numerous non-drug related incidents.”

Killed in police operations

Rappler spoke to the family of a 20-year-old man who was killed by policemen in an operation in Marilao, Bulacan, in August 2017. His case was one of the many cases of “nanlaban” (resisting arrest and fighting back), but his file could not be found in the folders either.

From July 1, 2016, to November 27, 2017, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) looked at 134 cases of victims of alleged drug-related extrajudicial incidents in Bulacan. CHR Central Luzon Director Leorae Valmonte confirmed to Rappler that his office monitored a lot of incidents where alleged drug personalities were killed in police anti-drug operations in the province.

“A huge number of these are a result of alleged police operations,” he said.

The Bulacan folders, although they did not contain files on a police-related death, showed that vigilantes were able to operate unrestrained in Central Luzon, as deaths occurred in the same areas on dates close to each other. (More on this in Part 3 of this investigative series.)

Rappler spoke with Central Luzon Police Chief Brigadier General Valeriano de Leon on the phone on February 5, and he said that, as far as they were concerned, they submitted complete documents.

“That is how they reported it to me. They submitted all requirements. Kapag may lacking diyan (if there are documents lacking), let the proper office require and they (police) will comply,” De Leon told Rappler. He referred Rappler to the chief of police in Bulacan, Colonel Lawrence Cajipe, who had agreed to an interview but has yet to provide a schedule as of writing.

Negros and Davao City files too

The Negros Occidental folders we studied contained files on 328 killings, only 4 of which were drug-related. The 286 were not drug-related, and the remaining 38 did not indicate anything. The circumstances surrounding the drug-related incidents recorded in Negros Occidental were the same – victims were gunned down by unidentified men riding motorcycles.

The Davao City folders contained only 62 killings, 8 of which were drug-related, and 54 not drug-related. Save for one stabbing incident, all of the victims (all adult males) in the drug-related killings were shot dead also by unidentified men mostly on motorcycles. Many of the victims were killed near or inside their homes.

Like Bulacan, the Negros Occidental and Davao City folders did not contain anything about deaths in police anti-drug operations. But data from the CHR obtained by Rappler showed that there were indeed police operations that led to deaths in these hot spots, even if the documents submitted to the SC showed otherwise.

Within the same period (July 1, 2016, to November 27, 2017), the CHR had proper documentation of 3 victims killed in police anti-drug operations in Negros Occidental, and 50 drug-related cases with 51 victims in Davao City. Similar to the dominant narrative in Duterte’s drug war, cops claimed self-defense in killings in police operations after victims allegedly fought back.

Legitimacy of the drug war

The incomplete submissions of the OSG, according to the CHR, “would cast doubt on the legitimacy of the police operations.”

If it had complete reports on cases of deaths in police operations, the Supreme Court can check pre-operation and post-operation accounts to see if the police had arrest warrants or even search warrants. These are tools to determine the regularity of operations and trace accountability.

The Deparment of Justice (DOJ) appears to have obtained copies of the nanlaban files, with Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra telling the United Nations Human Rights Council on February 24 that their review found the police did not follow rules in cases where their operations led to deaths.

The OSG had told the SC in its 2019 pleading that there was no conspiracy on their part (OSG and police) to “engage in a deliberate sabotage…it is pointless for the two venerable agencies to perpetrate such underhanded machinations.”

The last action taken by the SC on this case was almost a year ago, on March 3, 2020, the Tribunal’s Public Information Office told Rappler on February 22. Justices merely took note of CenterLaw’s manifestation that police operations in their clients’ community in San Andres Bukid, Manila, where 33 people were killed, were “illegitimate” and “violently conducted.”

Clearly, however, with incomplete data, it will be tough to determine the truth about what really happened during police operations that resulted in killings. The veracity of the police narrative in relation to their operations can only be firmly established by complete document submissions, CHR’s Valmonte said.

He added, “They keep on saying that they want to clean their ranks and what they’re doing is legitimate, but the best way to prove that is to show all the documents involved in the operations, so other bodies can scrutinize if all protocols were followed and, in fact, if the nanlaban stories are real.” (To be concluded: Part 3 | Vigilantes able to run amok in Bulacan)

– Rappler.com

This investigative series was put together by Rappler’s crime and justice cluster, composed of Lian Buan, Rambo Talabong, Jodesz Gavilan, Michelle Abad, and Pauline Macaraeg. Michael Bueza contributed to the visualization of data.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Ang low-intensity warfare ni Marcos kung saan attack dog na ang First Lady](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-liza-marcos-sara-duterte-feud-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=294px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newsstand] Duterte vs Marcos: A rift impossible to bridge, a wound impossible to heal](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/duterte-marcos-rift-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=278px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.