SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

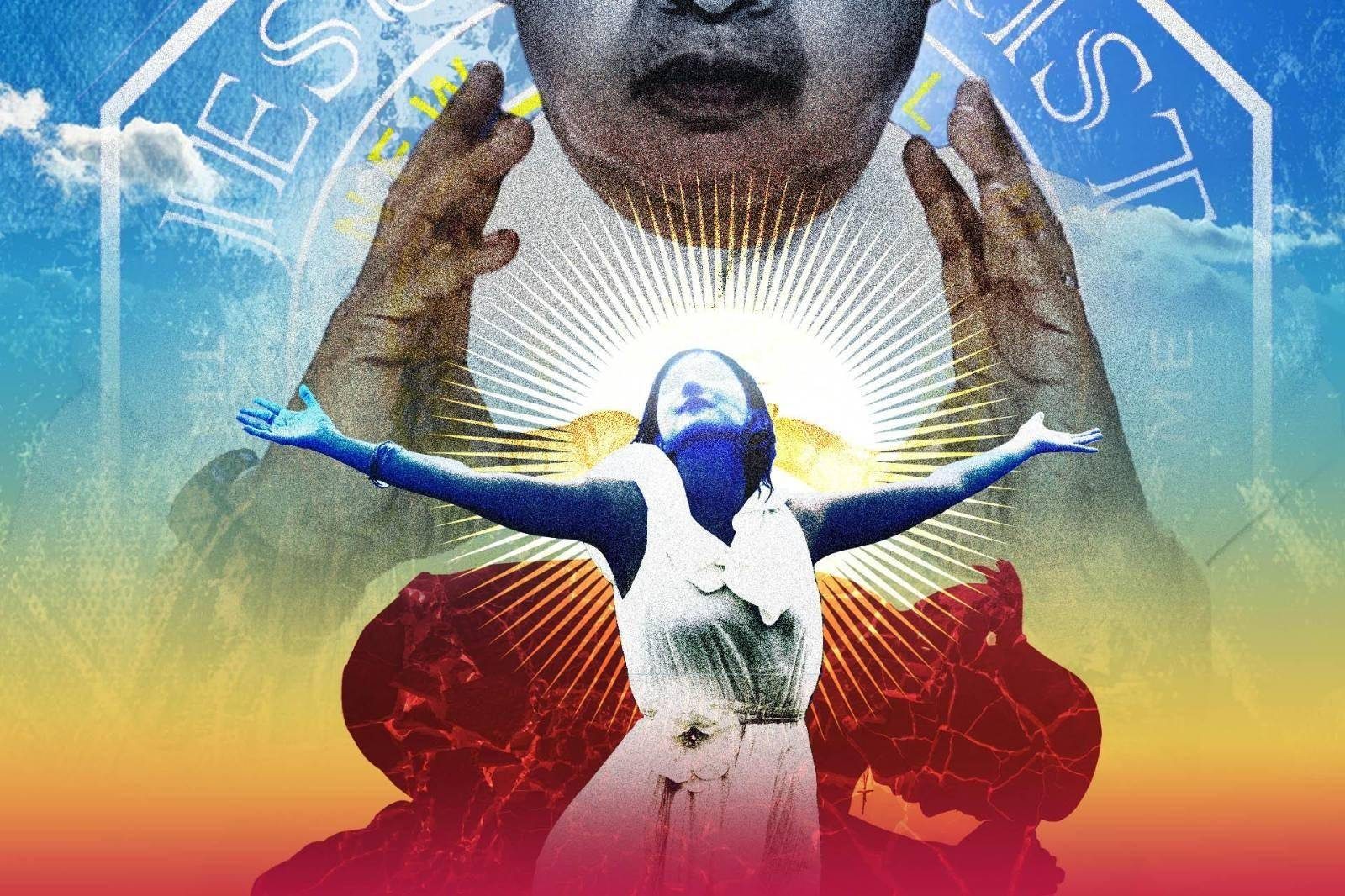

PART 1 | Quiboloy sexually abused women, minors – ex-followers, US prosecutors

PART 2 | ‘Root of all evil’: Quiboloy church’s demands for money mire followers in debt

It took a great deal of courage for a small group of women to tell Davao City-based Pastor Apollo Quiboloy’s church they had had enough, and to walk away and push back.

A mix of pride and years of conditioning rooted in fear kept dragging Minnesota-based Arlene Caminong Stone and Singapore-based Reynita Fernandez back into the clutches of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ (KOJC), the church founded by Quiboloy in Davao City.

“When you have been deceived, you don’t know that you are deceived. We were conditioned to suppress our feelings and opinions to the point that we forgot who we were,” said Stone, a former pastoral who served Quiboloy and his “spiritual wives.”

“You don’t question. Whether you understand or not, you don’t question. It’s called absolute obedience,” she said. Only those who could give that gained the trust for higher positions.

Stone, Fernandez, and Kentucky-based Faith Killion shared their ordeal with Rappler. They said leaving was complicated because of family members who remained loyal to the self-proclaimed “appointed son of God.”

In many ways, their life trajectories echo that of abused women who eventually escape physical and emotional violence after years of rationalizing their situation. It is also a common phenomenon among those coming out of “strong” churches, sociologist and Ateneo de Manila religion professor Jayeel Cornelio told Rappler.

“When you belong to a strict church, it becomes your identity. If everything, pati clothing mo (even your clothing), is determined, then it gives the impression that your free will has been subjected to the will of the ‘appointed son of God,’” Cornelio explained. “So the deconversion process, the out-conversion process, takes a much longer time than it does from somebody who came out of a loose church.”

A strong church is one that sets difficult conditions for membership, imposes harsh rules to remain in good standing, and hurls grave challenges at those wanting out, according to Cornelio.

The three women told Rappler that those who failed to meet KOJC’s strict behavioral codes or missed steep fund-raising quotas were whipped and caned, or suffered blows to their heads.

Quiboloy allegedly lashed Stone with a thick leather whip 60 times for merely going to the movies in Manila. The punishment was 20 lashes per movie. Stone said some companions received 120 lashes – for enjoying the same pleasures Quiboloy sampled during foreign trips.

Around 15 male members “screamed in pain until they became numb” after ministers rubbed siling labuyo (chili peppers) on their eyes and genitals, Stone and Fernandez said. One of their offenses: associating with a female outsider.

The men, who eventually left Quiboloy’s church, are in touch with Stone and her survivors’ support group.

Reprisals

US prosecutors on November 18 announced sex trafficking charges in Los Angeles, California, against Quiboloy and other KOJC officials. The 74-page indictment alleged that young victims were forced to have sex with Quiboloy or else be doomed to “eternal damnation.”

Quiboloy’s Hawaii-based lawyer, Michael Jay Green, brushed aside the former KOJC members’ accounts and the charges in the indictment papers, calling all these lies in a supposed international campaign orchestrated by a Nepalese and his family who left the Davao City-based church.

Green said the Nepalese, Shishir Bhandari, lied and struck a deal with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to bring Quiboloy and his church down in exchange for extended visas for himself and family members and a home in California.

Before leaving the KOJC, Bhandari served as operations manager of Quiboloy’s airline company, Apollo Air, that has been offering charted flights from Davao City to other areas in Mindanao. His wife, lawyer Lady Jade Canada, is the daughter of a former barangay chairman of Tamayong where Quiboloy’s eight-hectare “prayer mountain” is located. The Canadas were among the earliest Quiboloy converts in Davao City.

Green accused Bhandari and his family of embezzling KOJC funds.

Ex-members told Rappler they were at first silent when they left to avoid reprisals that US prosecutors said others had experienced.

Fernandez continued to support the church even after leaving full-time work, but said kin kept pressuring her to return to the old status. She did in 2016, when she was already based in Singapore.

Fernandez left for good in 2019. She didn’t say anything, except to warn her sister-in-law, without going into details, not to allow her daughter to become a pastoral.

But she said that was immediately followed by a big Zoom meeting where she was branded “a devil.” Fernandez’s brother denounced her at that same meeting and members were warned to cut all ties with her.

The 71-year-old Quiboloy is well-connected. A close friend and supposed spiritual adviser of President Rodrigo Duterte, his endorsement is sought by politicians during elections.

Cornelio said the religious group can easily get away with the excesses, given the political influence it holds – a far cry from the days when Quiboloy was just an ordinary preacher. As his organization grew, he further strengthened his grip on his followers with fantastic narratives about the origins of his power.

The ex-followers said they realized they were up against a well-oiled network of devotees who believed the preacher’s every claim of divinity and were willing to do anything – even lay down their lives – for their master.

“I think it’s going to be an uphill battle. It took the US, really, for us to become bothered like this,” Cornelio told Rappler.

Treated like outcasts

Many former church workers, especially those who stayed in the Philippines, felt threatened. “If I said these things in the Philippines, my head would probably be cracked open by now,” Stone said.

US federal prosecutors said the KOJC had a pattern of retaliating against those who left, sometimes accusing them of criminal misconduct and sexually promiscuous activity.

The emotional and psychological abuse was just as harsh, according to Killion.

Killion said she and others who left were demonized, threatened with damnation, and labeled as “backsliders” and “blasphemers” to be shunned by members.

Stone said it was both a punishment and a way of curtailing damaging information. “My older sister is still there with them, and we no longer communicate. They destroy families,” Stone said.

The former members said Quiboloy responds to critics with hostility – among them, the late televangelist Eliseo “Eli” Soriano, leader of another religious group, Ang Dating Daan.

When Quiboloy and Soriano engaged in an online spat years ago, Stone said the KOJC relaxed its rules on internet use to allow “cyber warriors” to launch a digital offensive against Soriano.

But the most violent reactions “are still reserved for former full-time workers and members, who are not only threatened with horrible amounts of karma from God’s wrath but real personal, social, physical, and legal dangers,” Killion said.

Struggle to get out

Cornelio said many survivors of KOJC abuse could be helped if the Philippines had a center that could aid the traumatized in their de-conversion. Conditioning often results in a pattern of behavior that continues outside of the church, he stressed.

Fernandez said finding Stone on social media helped her. While she knew personal pain, hearing about others surviving even worse firmed up her decision.

Even after distancing from the group in 2011, Stone said she still feared going to hell for turning her back on Quiboloy. In 2013, or two years later, she received a notice that she was removed as a member after efforts to talk her into returning failed.

While the KOJC caused lots of trouble for Stone, her response was being selfless, loyal, obedient, and pleasing to a man who claimed deity status.

Stone blamed her divorce from her husband on financial strains caused by her involvement with Quiboloy’s church. “I can’t blame him. He supported me while everything I earned went to Quiboloy’s group. It was like all the blood in me was sucked by vampires. That’s what they do – squeeze people dry and break families apart.”

Even after Stone left, she still found herself struggling because “I didn’t know how to handle relationships. I didn’t even know myself anymore.”

Stone said she also found herself unable to trust people: “I was afraid I would be deceived again.”

Surrender of will and reason

Quiboloy’s followers completely surrendered their ability to decide for themselves; to do otherwise was a sin, the elders told them. So, they unconditionally gave everything they could, according to Killion.

New members were expected to level up, especially after two years, said Fernandez. “Otherwise, they will say you are not growing spiritually,” she said.

Members were conditioned to think that the incessant giving of money was tied to salvation, and “to surrender all your money is to surrender your life with no questions.” That explains why workers engage in back-breaking street-level solicitations without expecting anything in return except for the promised “mansions in heaven,” Killion said.

Stone, Fernandez, and Killion overcame their fears to give other struggling members courage and to warn others from entering the hell they have escaped.

“This has been going on for 35 years. And nothing has changed, but it’s getting worse,” said Stone. “If nobody speaks up like us, nothing would change. And then this abuse will go on forever.”

79 overt acts

Although they have nothing to do with the case against Quiboloy in the US, the women said they felt they found an ally in Los Angeles-based federal prosecutors who announced the indictment on November 18. Their accounts were consistent with the alleged violations listed in the indictment document.

Aside from sex trafficking, the prosecutors enumerated 79 overt acts of the group concerning the charges of fraud and money laundering.

The victims were allegedly restricted from moving around as they wished, using coercion for “subjection to involuntary servitude and peonage,” with KOJC leaders keeping their passports and other important documents. Prosecutors said there was a conspiracy to fraudulently obtain US visas, and workers were told to lie to immigration authorities.

The workers were also allegedly made to look like they were traveling to perform in church concerts when they were begging in the guise of being Children’s Joy Foundation volunteers. They were sent across the US “nearly every day, year-round, working very long hours, and often sleeping in cars overnight, without normal access to over-the-counter medicine, and, at times, sufficient clothing.”

Often, they skipped meals and were housed in poor and communal living conditions, sharing rooms.

The workers were allegedly instructed not to mention KOJC, and to lie that their donations would be used to aid poor Filipino children. Those who failed to meet their daily quotas were often “yelled at, shamed, berated, physically abused, or forced to fast,” according to the indictment papers. Some were allegedly locked in rooms and made to listen to Quiboloy’s preachings.

Prosecutors said the collections were deposited in increments – not more than US$10,000 each – at different banks. Sometimes, money was also carried by those traveling to the Philippines “to fund, among other things, construction of a stadium and defendant Quiboloy’s lavish lifestyle.”

Warning: ‘Don’t get in’

The former Quiboloy followers said their experiences were consistent with the findings of US investigators and the indictment papers.

The women said they chose to speak up in the hope of making people think again before they join the KOJC, and call on its members to reclaim their right to think and make decisions on their own, free from the fear of divine retribution.

Stone said, “We are in the 21st century now. We have to use our freedom. We have to use our mind… We are doing this for the people who are still there, who are still trapped in the cage.”

Their message to them, according to Killion: “Do not go inside the kingdom of Pastor Apollo Quiboloy – just don’t even try it, if you don’t want your life to be miserable and destroyed.” – Rappler.com

Read the other stories in this series:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.