SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

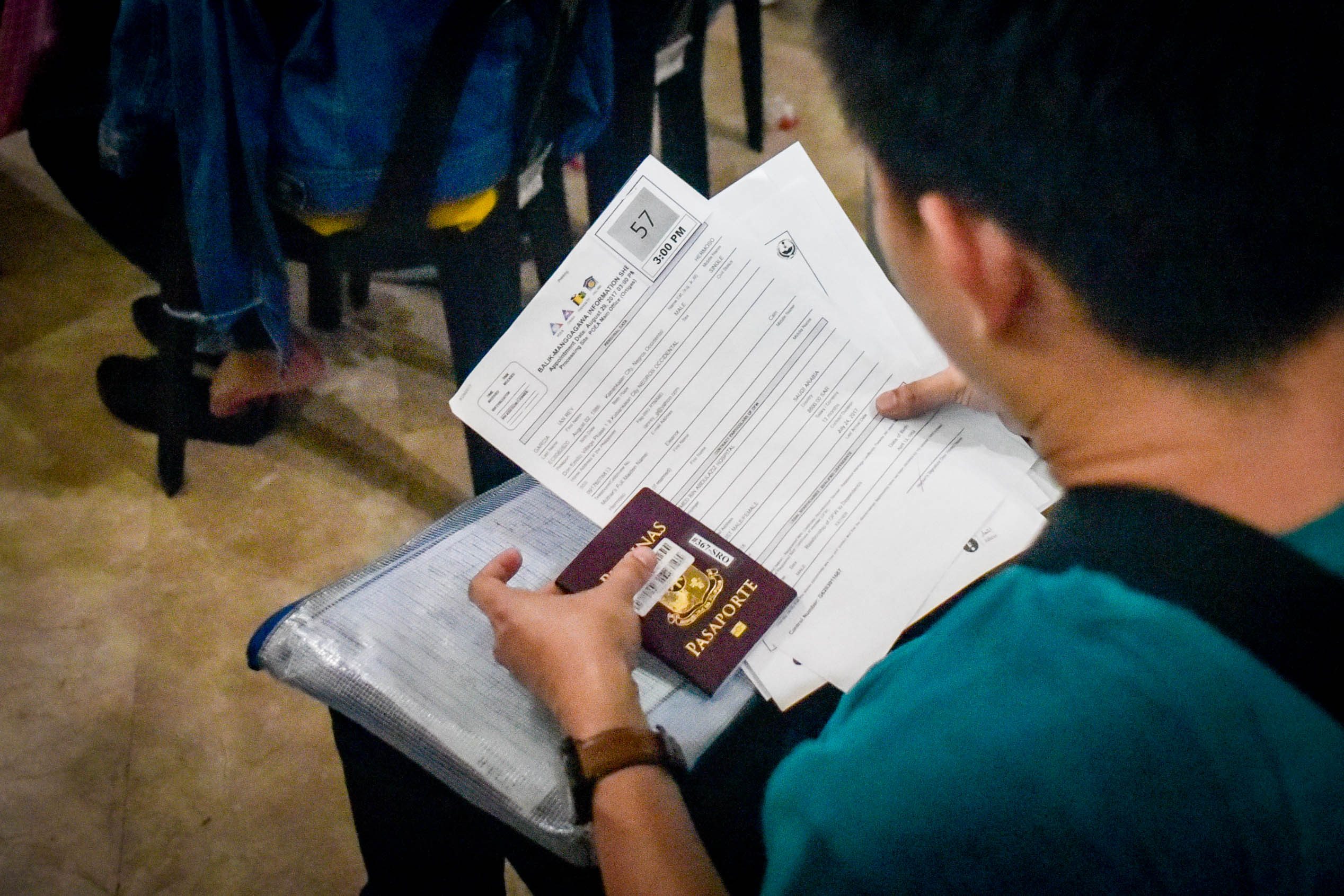

MANILA, Philippines – On a quiet February morning two years ago, Hajji took his place among the hundreds of Filipinos in lines that snake toward the gates of the Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA). With luggage in hand and an envelope of documents tucked tightly between his arm and chest, he readied himself to leave his family.

Hajji had hoped this day would come. He’d been planning for it for quite some time. 6 months worth of constant back and forth from Bataan to Manila for paperwork and permits had secured him a job as an electrician in Doha, Qatar.

Working as a plumber for 8 years, Hajji left a stable but low-paying job in the Philippines on the promise of better pay.

But to get to Qatar, he had to pay a price.

“Bali nagbayad ako ng P41,900 kasi kailangan daw ng recruitment agency para puwede na akong umalis,” Hajji said. (I ended up paying P41,900 because the recruitment agency said it was needed so I could leave.)

To secure the chance to work abroad, Hajji had to scrounge for P41,900 to pay for all the fees assigned to him by his recruitment agency. The amount was nearly twice the monthly salary of about P23,800 he had yet to earn in Qatar as a worker for Megatec, a company that subcontracts mechanical and engineering work to construction companies.

With little to no savings of his own, Hajji and his wife took out a loan of P50,000 to cover the expenses. He would pay back the loan over a one-year period by making 12 equal monthly installments of P6,400. By the end of the repayment period, Hajji would have paid P76,800.

At the time, the monthly payments seemed reasonable enough to Hajji and his wife. They had no idea that he would go for months without being paid and eventually stranded in Qatar. The loan exceeded its one year period, piling up to a mountain of debt barely paid till today.

Laws protecting migrant worker rights set limits on recruitment fees and exempt some sectors from paying. Seafarers, domestic workers, and all workers bound for countries that prohibit collection of placement fees (United Kingdom, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, Japan) are all exempted from paying recruitment fees.

Under the “employer pays” model, some recruitment agencies do not even charge recruitment fees at all. Despite these legal frameworks, migrant workers like Hajji end up falling into debt bondage.

However, paying high placement fees has become an accepted part of working abroad. As Erwin, a worker who left with Hajji, put it, “Kung sobrang nauuhaw ka at may taong nagbebenta ng tubig, kahit mahal talaga yung presyo, bibilhin mo yung tubig, ‘di ba?” (If you were so thirsty and someone was selling water, even if it was being sold at a high price, wouldn’t you buy it?)

Placement fees

“We know why Filipinos work abroad – money. The desire to go abroad is (strong),” added Maria Teresa de los Santos, officer-in-charge of the worker education division of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA).

So strong is this desire that migrant workers overlook excessive recruitment fees and simply take out loans to pay for them.

Labor rights group Migrante International reported that as of 2015, about 6,000 Filipinos leave daily to work abroad. Like Hajji, many of these migrant workers shell out large sums of money that are often times incurred through loans to pay for recruitment fees.

“We tell them (OFWs) about loans, the modus operandi of illegal recruiters, lending agencies, different (information). If an applicant inquires about an agency and we advise them not to complete the transaction, they still do,” said lawyer Cora Toldanes of the POEA’s prosecution division.

The charging of recruitment fees to migrant workers is not prohibited, but the law sets limits on the amount that can be charged.

Republic Act 9042 (RA 8042) or the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipino Act, states that a recruitment agency can charge a worker up to one month’s salary for recruitment fees, as outlined in the employment contract. Special guidelines also exempt household service workers and seafarers, who in 2015, comprised more than half of deployed OFWs, from paying any placement fees at all.

Despite this, the practice of charging placement fees at exorbitant rates remains to be a common practice in the Philippines.

“Isa sa pinakamadalas na nava-violate doon sa RA 8042 ay yung placement fee. Clear na policy yan, pero marami pa rin talaga sa mga placement agencies ang naniningil. Actually, iniiba lang nila yung pangalan,”said Arman Hernando, spokesperson for Migrante International.

(One of the most common violations of RA 8042 is the placement fee. The policy is clear but many recruitment agencies still charge (high rates). Actually, they just change the name.)

Ellene Sana, executive director of the Center for Migrant Advocacy said that recruitment and lending agencies often work hand in hand to circumvent the zero placement fees policy for domestic workers and seafarers. They charge workers for training or language classes which often come out to be higher than allowable recruitment fees.

“This is a big issue for us, particularly in the case of our migrant domestic workers. Under the HSW policy reform package, (they should have) zero placement fees. That is good. But what developed is, suddenly there are requirements…This is where people complain that there are no placement fees but there are suddenly training fees that they need to pay for. This is one way they (agencies) work around the policies of POEA,” Sana said.

She added, “That’s really a blind spot because when we got to POEA to complain, they relay (our complaint) but their concern is the (recruitment) agency. Not the lending agencies, not the training institutions.”

Hussein Macarambon, project coordinator for the International Labor Organization (ILO) in Manila also said: “Placement fees, which are now disallowed by law, are reshuffled to other recruitment-related processes such as training or medical examination. The government should look closely into standardizing and regulating the role of training centers and medical clinics that provide services to Filipino migrant workers.”

In Hajji’s case, this means that an amount of P23,800 for placement fees make for the allowable recruitment fee. In reality, however, Hajji paid his recruitment agency a total of P41,900.

| Requirement | Fee |

| Recruitment and processing fee | P37,500 |

| Medical exam | P3,500 |

| Document authentication | P400 |

| Agent (who facilitated document processing at NAIA) | P500 |

| Total | P41,900 |

According to Hernando, the charging of high recruitment fees is a form of illegal recruitment and is one of the most common labor complaints they receive from OFWs.

He estimated that Migrante receives about 5 to 10 complaints regarding illegal recruitment daily – with at least one always pertaining to excessive recruitment fees.

Meanwhile, fees needed for other destination countries can go much higher.

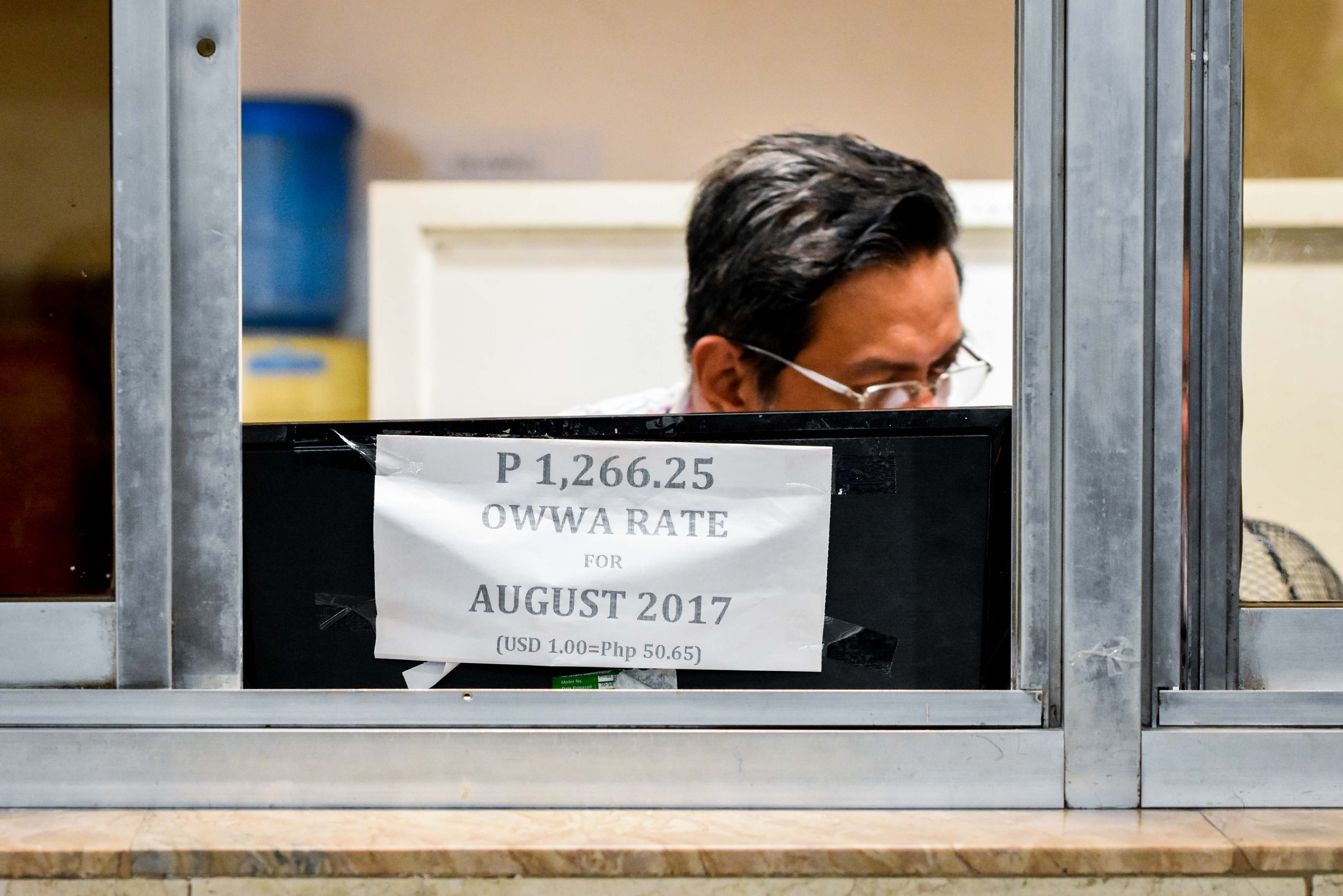

According to a policy brief from Migrant Forum in Asia (MFA) – a regional network of non-governmental organizations, associations, and trade unions, OFWs pay anywhere from $551 (P28,211) to $7,000 (P358,400) depending on which country workers go to.

A low of $551.80 (P28,252) in approximate fees were observed for OFWs headed for South Korea, whereas approximate fees for OFWs bound for Taiwan were anywhere between $1,400 (P71,680) for a domestic worker and up to $3,200 (P163,840) for a factory worker. The highest fees of $7,000 (P358,400) were also observed for OFWs with food processing jobs in Canada.

The report likewise said that the biggest determinant of the amount workers would pay to secure a job placement is the anticipated wage abroad.

“Migrant workers headed for countries in which the minimum wage is higher tend to pay higher fees. The higher the wage promised by the recruiter, the more they are likely to be willing to pay to secure a placement,” it said.

Meanwhile, OFWs turn to a number of sources just to secure the funds needed.

While some sell material possessions to convert them to cash, others take out loans with high interest rates from lending agencies or informal lenders also called “5-6”. Those who can, turn to friends and family.

Zero-placement fee

In its policy report on recruitment fees, MFA cited Verité, a fair labor practices advocacy group, which estimates that recruitment costs can take up as much as 62% of a worker’s anticipated wages.

Along with high costs, the number of parties involved in the recruitment process contributes to misleading migrant workers.

MFA, along with the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Private Employment Agencies Convention, said that to mitigate these risks, which can lead to situations of debt bondage and forced labor, zero placement fee practices must be adopted. (READ:PH to be test country for ILO’s fair recruitment project)

“Eliminating recruitment fees for workers is necessary to alleviate the problems of debt bondage and forced labor for migrant workers… Workers are often willing to make significant investments in job opportunities abroad and to take on debt to do so. The same cannot be said for employers,” it said.

Marie Apostol, chief executive officer and founder of Fair Hiring Initiative, a recruitment agency in the Philippines that puts emphasis on its “no-fee-to-jobseekers” policy, believes that charging excessive recruitment fees to migrant workers can give way to forced labor.

“We found the links between recruitment and exploitation were that they migrant workers) suffered. And they seemed to suffer willingly. We found that they (migrant workers) couldn’t leave their jobs abroad, even in cases of maltreatment, because they had paid enormous amounts of money in their home countries to get the job,” said Apostol.

She added, “There was an element of involuntariness because there was a penalty. Also, if they left (their work abroad) they would have had to forego everything that they had sacrificed and had put up (with) to find the money to pay for their jobs.”

For Apostol, this was part of the reason why Fair Hiring Initiative was set up.

“When we started seeing these issues, we said to companies, you have to use a labor agent that will not take money from your workers,” she said.

Aside from not charging its workers a placement fee, Fair Hiring Initiative also includes in its model a transparent employment process where both employees and employers are aware of all details, fees, and steps required to provide and obtain work abroad.

The agency also selects and places prospective workers based on skill, affording it the option of passing on recruitment fees to employers instead of employees.

With this scheme, Apostol said the agency’s revenue comes “solely from employers”.

Pilot country

ILO named the Philippines last year as pilot country for its “Integrated Program on Fair Recruitment” or FAIR where over the 3-year course of its program, the Philippines “will contribute to a global knowledge system on what works and does not work with respect to fair recruitment practices,” said the ILO.

The program will also use best practices and knowledge gathered to address the regulatory and enforcement gaps in achieving fair recruitment practices.

“Possible kasi. That’s why sometimes, we tell the workers, if there’s a sign ng agency ganito na maningil, iwanan mo na. Go to another agency because may agency naman na matino,” De los Santos said.

[It’s possible (to recruit legally). That’s why sometimes we tell the workers, if there’s a sign that an agency charges like this, leave them. Go to another agency because there are agencies that are judicious.]

Through ILO’s program findings, possible issues with a zero-placement fee policy may also be addressed.

MFA reported the need to couple the abolition of placement fees “with appropriate monitoring mechanisms and harsh sanctions for those who violate this rule.” Proper regulation is needed to avoid situations where employers may feel as though employees can be “controlled” due to the high fees incurred to secure labor provided by migrant workers.

“The employer pays” model

The Institute for Human Rights and Business said that the “employer pays” model also benefits companies; workers will be more likely to stay to be more productive.

Manufacturing giants Coca-Cola, Hewlett-Packard Enterprise, IKEA, and Unilever certainly think so. Joining forces with other labor rights groups like International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Verite, they formed the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment and committed to championing the “Employer Pays Principle“ so that no worker would have to pay for a job.

Both De los Santos of POEA and Apostol believe that a big impact on current recruitment practices can come from employers.

“The market for an ethical recruitment needs to grow. It’s a work in progres. We need to build the employer paying market for us to get to that point where there are more non-fee charging agencies,” said Apostol.

De los Santos added, “It really depends on the employer. If they (recruitment agencies) get fees from the employer, they shouldn’t be charging the placement fee (to migrant workers) anymore.”

Apostol also said that employers who take on the costs of recruiting workers from abroad can help ensure a more ethical recruitment process: “Once the employer starts paying, then they have leverage, then they can choose what kind of workers and agents will be used in the Philippines. They can be involved in the due diligence.”

“Until then, the need for a job overrides the known risks,” she said – Rappler.com

*$1 = P51.2

Reporting for this project was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.