SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

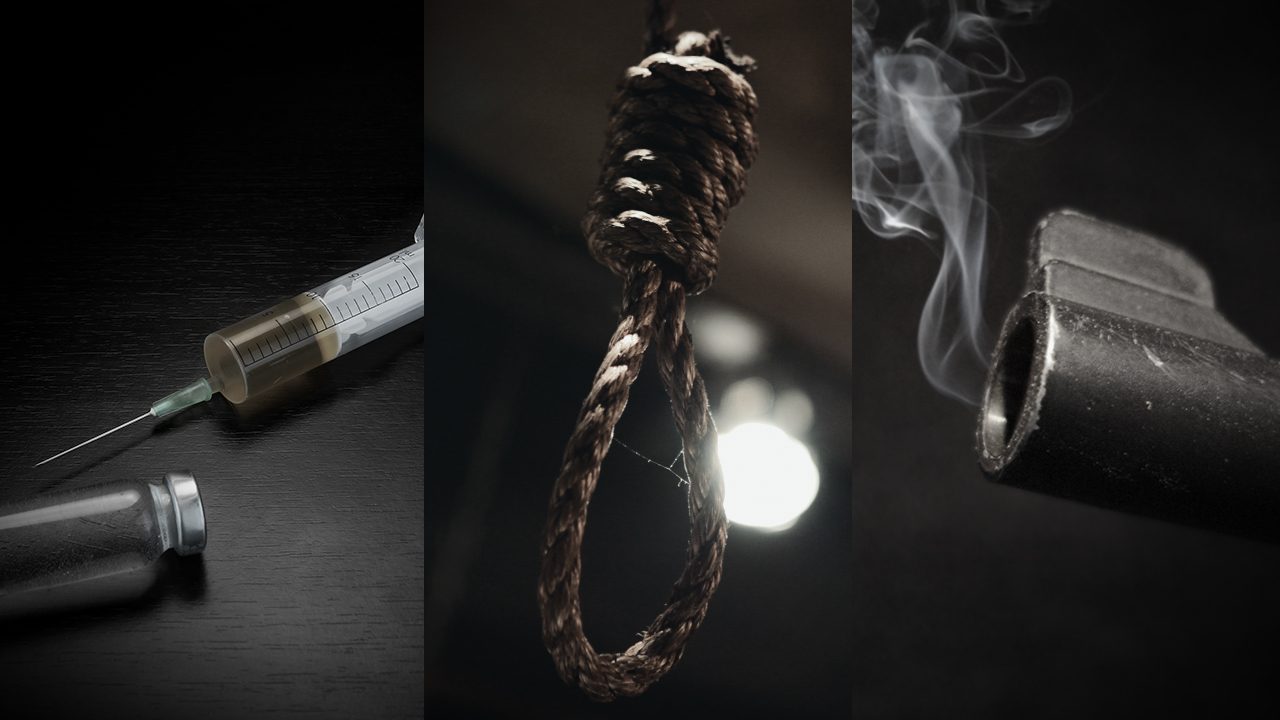

In President Rodrigo Duterte’s 5th State of the Nation Address (SONA), the chief executive called on Congress to reinstate the controversial death penalty for violators of the country’s anti-drug law.

“For me, a shabu is a shabu is a shabu […] It’s a crime in Malaysia, especially in China, it’s a death penalty. Malaysia, it’s a death penalty. Indonesia metes out a death penalty. Tayo lang ang Pilipinas maarte (Only we in the Philippines are stubborn),” Duterte said in a mix of English and Filipino during his August 17 address that was expected by many to focus on the country’s fight against the coronavirus pandemic.

Instead, Duterte found time to insert the death penalty, seeking its revival for the third time after it was abolished by former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in 2006. Never mind if the Philippines is a state party to the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which bans executions.

In the 3 countries Duterte mentioned – Malaysia, China, and Indonesia – has the death penalty worked as a deterrent to drug-related crimes and have concerns been raised, too, about human rights violations? Here’s what we found.

Malaysia

The illegal drug trade in Malaysia has long taken the world stage. Historically, the problem traces its roots to the Chinese community’s use of opium, which was sanctioned and taxed by the British during their occupation of Malaysia in the late 1700s to 1800s.

Malaysia’s Dangerous Drugs Act of 1952 makes the death penalty mandatory for drug trafficking. Many of the persons on death row, however, have claimed they were coerced or manipulated into bringing small amounts of drugs into Malaysia.

A recent 2019 Amnesty International (AI) report revealed the use of torture and other methods to obtain “confessions.” Suspects had “inadequate” access to legal assistance, and Malaysia had an “opaque” pardons process. There were also reports of unfair trials and secretive hangings.

AI also reported that 73% of those on death row – 930 of them – have been sentenced to death for drug-related offenses. More than half were foreigners.

Despite a significant number of death sentences for foreigners, other than in courtroom proceedings, Malaysian law does not provide for any interpreter services to support defendants who don’t speak Malay. AI said there are reportedly cases of people being made to sign documents in Malay, despite not understanding the language.

“While some pro-bono initiatives exist, access to these services is controlled by prison officials, and there is no transparency over how access is granted or not,” the AI report read.

According to the rights watchdog, no evidence supports the claim that the death penalty is a unique crime deterrent or a deterrent to drug use in Malaysia.

Malaysia’s Dangerous Drugs Act, which provides for the death penalty, is just one of several legislative efforts meant to crack down on illegal drugs.

Yet the drug problem in Malaysia has persisted, with an estimated 140,000 “registered” addicts by 1991. By 2018, official statistics still showed Malaysia recorded 25,267 registered addicts. While the numbers in other states decreased, some Malaysian states reported an increasing trend.

After the May 2018 election, winning coalition Pakatan Harapan imposed an official moratorium on executions and promised to revoke mandatory death by hanging in all laws. As of posting, the government is still deliberating on whether or not it would abolish it.

China

In China, executions have been traditional – stretching all the way to the ancient times when strangulation, decapitation, and even slicing of body parts were practiced. Public executions were used to educate and influence the general public into obeying the government.

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, capital punishment was used extensively in the 1950s and 1960s primarily to target political offenses. China’s criminal law provides for at least 40 crimes punishable by death, which include drug trafficking, homicide, and property crimes.

AI names China as the “world’s leading executioner.” Humanitarian organization Dui Hua estimates around 84,000 executions happened between 2002 to 2018. The exact numbers of death sentences actually carried out in China remain a state secret.

Human rights issues have prevailed as a 2015 HRW report revealed how death row convicts were mistreated. “Prisoners with death sentences are guarded more strictly. Once the sentence is handed down, they have to wear handcuffs and leg irons … their hands and feet are shackled together, they cannot stand up straight, for usually between 8 months and a year between their sentence and execution,” Beijing-based human rights lawyer Ze Zhong told HRW.

HRW also reported deaths under custody due to torture, which was used to exact forced confessions in violation of its Criminal Code.

While Chinese regulations have a protocol for handling deaths in custody, how authorities actually handle deaths “appears to vary considerably,” said HRW. Police tell family members of the deceased that the detainee died of “natural causes,” but in most cases, it was unclear whether authorities conducted an investigation.

Much has yet to be known about the particulars of the death penalty in China. While there is a lack of evidence on how the capital punishment affects crime, government figures show a decreasing trend in registered criminal cases from 2015 to 2018. But experts doubt official figures, such as Borge Bakken who studies crime in China at the Australian National University. In a January 2019 BBC report, Bakken claimed the crime statistics were lies and propaganda.

Indonesia

The Indonesian death penalty is based on the country’s Criminal Code, which defines capital punishment as execution by shooting. Meanwhile, Indonesia also has Law No. 39 of 1999 covering human rights, and which declares that the right to life is inherent in humans and cannot be diminished.

Indonesian authorities justified the death penalty as they saw the country being in a “state of emergency” with regard to drug abuse. In December 2014, newly-sworn-in President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo said he would not grant clemency to 64 drug convicts on death row, as there was “no forgiveness” for drug dealers.

In its 2015 report, AI said it had recorded cases of unfair trials and weak administration of justice leading to “arbitrary” deprivations of life. AI found that defendants in some cases did not have consistent access to legal counsel, and were subjected to maltreatment while in police custody to make them “confess” to their alleged crimes.

“Many [of the 2015 death convicts] were vulnerable, victims of police or other violence, drug couriers, mentally impaired, targeted because of the color of their skin, or tortured into making a confession in the absence of any evidence,” said a March 2020 report from rights organization LBH Masyarakat.

In 2016, Widodo said the government wanted to move towards removing the death penalty, and that it was “very open to options.” Indonesia reportedly has not carried out executions since July 2016.

But even after 2016, Indonesia continued to sentence people to death. According to data from research organization Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR), as of October 2019, there are 274 death row inmates awaiting their execution date. At least 58 of them have been on death row for 10 years.

“It is not uncommon to find stories of death row inmates suffering psychological trauma resulting in a decreased quality of health, both physically and psychologically,” the ICJR report said.

In an April 2019 Jakarta Post report, Indonesian lawmaker Charles Honoris said the capital punishment was ineffective in curbing crimes – even drug offenses, as drug-related cases have persisted. Similarly, the ICJR said there is little proof that the death penalty is an effective crime deterrent.

Activists have been calling for the abolition of the death penalty in Indonesia, highlighting the dangers it poses as judicial systems remain prone to error. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.