SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – When President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. announced he would take on the role of agriculture secretary, it was inevitable that his father’s legacy in agriculture would come to mind. The Marcos agricultural program that is easiest to recall is Masagana 99, and Marcos Jr. appears to be harking back to it by entertaining recommendations to implement a new version – dubbed “Masagana 150.”

How will this new iteration of Masagana 99 differ from that of the first Marcos’, which had been called both a success and failure by the former government officials who implemented it, as well as by agricultural experts?

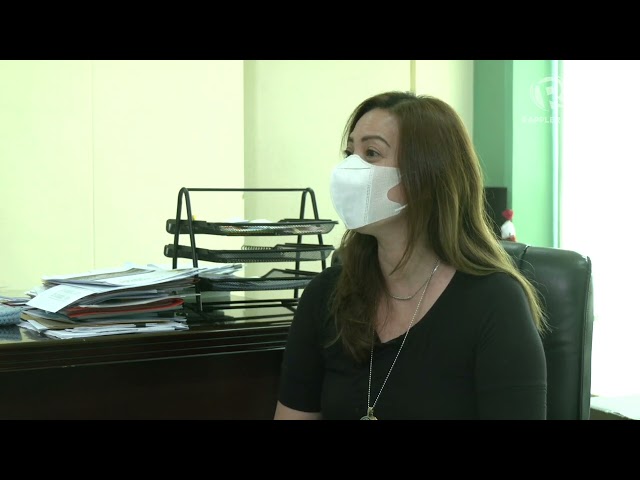

Agriculture Undersecretary-designate and spokesperson Kristine Evangelista explained the program to Rappler in an interview on Friday, July 22. She stressed that Marcos has yet to approve the program but that it is one of the department’s recommendations to him, in line with his number one marching order to increase the production of rice, corn, vegetables, poultry, and pork.

“The Masagana 150 is about increasing the yield. We are pushing that for, every hectare, there will be 150 cavans produced. So that is in the part of the marching order of how to increase the yield of our farmers,” Evangelista told Rappler.

Masagana 150 was one of the programs proposed by previous agriculture secretary William Dar for his successor. In Marcos’ first meeting with agricultural officials, the President called it, and a similar program called Masagana 200, “good plans.”

“Let’s operationalize them already,” Marcos said then.

Let’s compare the programs.

99 vs. 150

If Marcos does end up implementing Masagana 150 in his first year as President, it would have been 49 years since his father established Masagana 99.

In simple terms, Masagana 99 was a program that offered farmers a package intended to increase how much palay they can harvest from their land, which they would be able to afford through a credit program with rural banks, coordinated by the government.

The technology package comprised of high-yielding rice seeds (seeds that grew into plants that had more grain than other varieties), low-cost pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizer. Farmers then took out loans from rural banks to be able to purchase this package.

Through this package, the government aimed for 99 cavans of rice to be produced for every hectare planted with palay, hence the name.

Masagana 99, begun in 1973, was initially successful. It managed to significantly increase rice production, even allowing the country to reach rice self-sufficiency for a few years, according to this review of Philippine agricultural policies.

In May 1974, or a year after it was launched, 36% of 1.13 million small rice farmers availed of loans for the program, according to National Scientist Emil Javier. Collection from farmers for the repayment of those loans was at 90%.

But by 1980, repayment for loans shrunk to 35% or lower, and only 3.7% of small rice farmers were taking out loans. Because farmers couldn’t pay up, 800 rural banks went bankrupt, according to former finance secretary Carlos Dominguez III in that famous exchange with presidential sister Senator Imee Marcos.

Dominguez was the agriculture secretary of the Cory Aquino administration that succeeded the Marcos dictatorship.

Small rice farmers were buried in debt. Dependence on the Masagana 99 pesticides and herbicides damaged the environment. The program was scrapped in 1984, or 11 years after its promising launch.

Learning from mistakes?

The country’s current average yield per hectare is 90 cavans of rice, according to former agriculture secretary William Dar in a Rappler interview before the turnover to the Marcos administration. In 2021, the country attained a record-harvest of 19.96 million metric tons, which brought the country to 92% rice self-sufficiency, said Dar.

The challenge for Masagana 150 is to increase that by at least 60 cavans at a time when the cost of fertilizer has tripled, oil prices are contributing to high transportation costs for crops, and the specter of destructive typhoons and pests is ever-present.

But Evangelista says one way Masagana 150 will be different from Masagana 99 is its credit program. The Department of Agriculture (DA) now has more experience and a more institutionalized structure for giving loans to farmers.

“Now, we have ACPC, the Agricultural Credit Policy Council. Even before, it has been giving loans to our farmers at zero interest. It also involves rural banks to ensure the loans are being paid and it is also something with the terms that are realistic based on our stakeholders,” she said.

The ACPC was created in 1986, or the year the first Marcos president was deposed. One of its purposes is to “review and evaluate the economic soundness of all agriculture and fisheries credit programs” and “synchronize” all such credit policies and programs.

It’s also mandated to increase its fund base and use other ways to ensure its financing programs are sustainable.

One of its existing programs is Sikat Saka, which provides rice and corn farmers with access to credit, in partnership with the Land Bank of the Philippines. It had a loan program for small rice farmers and micro enterprises during the COVID-19 quarantine period. It has a credit program for young agri-entrepreneurs and agrarian reform beneficiaries.

The hope is that, with an institution like ACPC, a credit program for the proposed Masagana 150 would be better equipped to run a sustainable loan program for farmers.

But because Masagana 150 is still at the recommendation phase and details of the program are still being hashed out, it’s still unclear how the credit program would be run.

There’s also nothing final about the type of rice varieties that would be prioritized by the program, and what fertilizers and pesticides would be made to go with them. Will there be studies to make sure recommended pesticides don’t harm the environment?

“The type of seeds and fertilizers is being studied by our rice group because, of course, sustainability is very important and accessibility to these seeds and fertilizers as well,” said Evangelista.

Any program geared towards boosting rice production would entail complementary efforts in improving irrigation coverage and giving farmers machines that could help in planting and harvesting.

Masagana 150 is still very much on the drawing board and the soonest it would have a budgetary allocation is next year, the year when the government budget is one that the Marcos administration has crafted. Marcos is still working with the last budget drawn up by the Duterte administration.

“We are working on the details and the operational plan is very important. The details on how it will be implemented will also mean specifying budget allocations and defining the timelines,” said Evangelista. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.