SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

For the rest of the special powers that the Senate gets to exercise, all will be dependent on what the lower chamber initiates – such as impeachment proceedings,1 granting or withholding of public utility franchises, and the annual national budget.

If the House of Representatives in the first half of Duterte’s term was cooperative with, if not a rubber stamp of, the Executive, the profile of the incoming members does not promise any drastic shifts in the chamber’s inclinations.

Among the 243 district representatives who have won, 121 are reelected, 63 are replacing their relatives, and 59 are “new” – meaning, they used to be congressmen or women, or have held other elective positions before joining the House.2

The groups traditionally expected to keep a critical eye on the administration’s legislative agenda – the political opposition and progressive party-list representatives – have been diminished in the last polls.

Only 18 Liberal Party members were elected as district representatives. Days before assuming their new terms, many of them expressed openness to rejoining the majority bloc, if the right Speaker could accommodate them.3

Progressive party-list organizations dislodged

Sixty-one party-list representatives, from 51 organizations (out of the 134 that participated), were proclaimed by the Commission on Elections (Comelec). Some of the progressive sectoral groups that had won seats in previous elections failed to get the votes this time, while neophyte organizations endorsed by Duterte, political families, or media personalities garnered enough numbers.

Among those that failed to keep their congressional seats were Akbayan4 and Anakpawis5 – which had won in several election cycles before 2019. Leftist organizations Bayan Muna, Gabriela, ACT Teachers6, and Kabataan still won seats, but their campaign this time had to contend with the Duterte government’s red-tagging, which started almost a full year before the campaign period7 and accusations that they were among those plotting to oust the President.

While the negative campaign by the state could be a factor in the difficult campaign for the progressive groups, further study may be needed to fully explain the decline in the votes of some of them in 2019. Kabataan, for instance, has seen its vote decline every election since 2010.8 Gabriela and ACT Teachers saw dramatic drops in votes from 2016 – more than halved, in fact – but their votes had been fluctuating at least since 2010.9 Yet Bayan Muna saw the number of its votes nearly doubled from 2016 to 2019 – from 606,566 to 1,112,97910 – amid the red-tagging.

It was Akbayan, which was allied with the so-called yellow crowd of the Liberal Party, whose vote base was practically wiped out. While its votes had been decreasing every election at least since 201011 (the year it garnered more than one million votes for the first time), the decrease has been steepest during Duterte’s time. From 1,061,947 in 2010, the votes dropped to 829,149 in 2013, then to 608,449 in 2016 (Aquino time), then finally to a mere 173,356 votes in 2019 (Duterte time).

Pulse Asia’s party list surveys during the campaign period captured the shift in voters’ preferences amid the Commander in Chief and the military’s propaganda12 against his former Leftist allies, and the open call of presidential daughter Sara Duterte for voters to reject the organizations that were part of the Makabayan bloc in Congress.13

The March 23-27, 2019, survey showed 14 groups were likely to get at least 2% of the votes and win a seat. All of them, except one (Magsasaka), had representatives in the 17th Congress. They were: Bayan Muna, Magsasaka, Gabriela, Ako Bicol, A Teacher, Senior Citizen, Buhay, Akbayan, Amin, An Waray, Kalinga, Anakpawis, Cibac, and Angkla.

In the April 10-14 poll, 13 organizations were likely to win a seat, and only less than half remained from the March choices.14 Seven were new in the possible winning list: ACT-CIS, APEC, Agap, Probinsyano Ako, Anac-IP, Ang Probinsyano, and Coop-Natcco.15

In the May 3-6 survey, a little over a week before Election Day, only 9 appeared assured of getting a seat each. Of these, only 5 were in the winning list since March;16 two were newcomers which had been in the list since April (ACT-CIS and Ang Probinsyano); and two entered the winning list only now (1 Pacman and An Waray).17

Of the 51 organizations that won seats through the party list, 11 were endorsed by President Duterte, the party of his daughter Sara, or had campaigned for Duterte’s senatorial candidates Christopher “Bong” Go and Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa.18

Locally-targeted campaigns

An insight often ignored every election is that even in races for national positions – where media advertisements and endorsements of national figures are given prominent credit – it is the local vote bases that deliver.

I have pointed out that there are no real national political parties in terms of organization because their membership and vote-delivery capability are dependent on which local and regional parties are in coalition with them during a particular election cycle.19 Those local and regional parties, led by local politicians, are the ones that have the warm bodies and the grassroots networks.

The results of the 2019 senatorial and party-list elections bear this out.

While senatorial candidates on the slates of PDP-Laban and Hugpong ng Pagbabago had the backing of President Duterte and his daughter Sara, their individual efforts to draw on provincial and regional ties or alliances with local networks were evident.

Imee Marcos, while ending up only 8th in the national count, topped the elections in the northern Philippines, not just her home region of Ilocos. She got the highest vote in Ilocos Region and the Cordillera Administrative Region, grabbing the No. 1 spot in all provinces, except Pangasinan (in Region I) Benguet, Ifugao, and Mountain Province (in the CAR). She landed second in Cagayan Valley, another region where Ilocano is spoken; she topped the race in Cagayan province.

Bong Go was No. 1 in 5 of the 6 regions in Mindanao; second to Villar in Soccsksargen. He got the highest votes in 21 of the island’s 26 provinces. Fellow Davaoeño and favored candidate of President Duterte, Ronald dela Rosa, while he was only second to Go in the regional count in Davao, topped Davao del Norte and Davao Occidental.

None of the opposition Otso Diretso candidates won in the national count, but 4 of them – Bam Aquino, Mar Roxas, Chel Diokno, and Gary Alejano – made it to the Top 12 in Bicol. This was the case in 5 of the 6 Bicolano provinces; in Masbate, only Aquino and Roxas got winning slots. In fact, Aquino topped the race in Camarines Sur, the home province of his party mate and Otso’s main campaigner, Vice President Leni Robredo.

Independent reelectionist Grace Poe, who was No. 2 in the national count, topped only one region, Bicol, which was not even one of the 7 regions where she ranked first in the 2013 senatorial polls. One explanation for Poe taking Bicol could be what happened in 2016, when she ran for president – governors in the region crossed party lines to endorse her at a time when rival Rodrigo Duterte had overtaken her in the surveys. Most of these politicians were still in power during the 2019 campaigns. In addition, Poe’s running mate in 2016, former senator Francis Escudero, was in 2019 running for governor in Sorsogon, one of the Bicolano provinces.

Home provinces, to which candidates maintained strong ties, also delivered for their sons and daughter against the odds of popularity ratings:

- Joan Sheelah Nalliw, an independent, ended 52nd in the national count, but got the highest number of votes in her home province of Ifugao.

- Mar Roxas, a former senatorial poll topnotcher (in 2004) and presidential poll second-placer (2016), was 16th in the national count, but was No. 1 in his home province of Capiz.

- Glenn Chong of the Katipunan ng Demokratikong Pilipino ranked 31st nationally, but topped the count in Biliran, where he served a term as congressman (2007 to 2010).

- Samira Gutoc, of Otso Diretso, was 25th in the national count, but was No. 1 in Lanao del Sur, her home province.

Even in the party list races, where campaigns are supposedly done for, and on behalf of, sectors, organizations depend on particular geographic bases to deliver the votes for them.

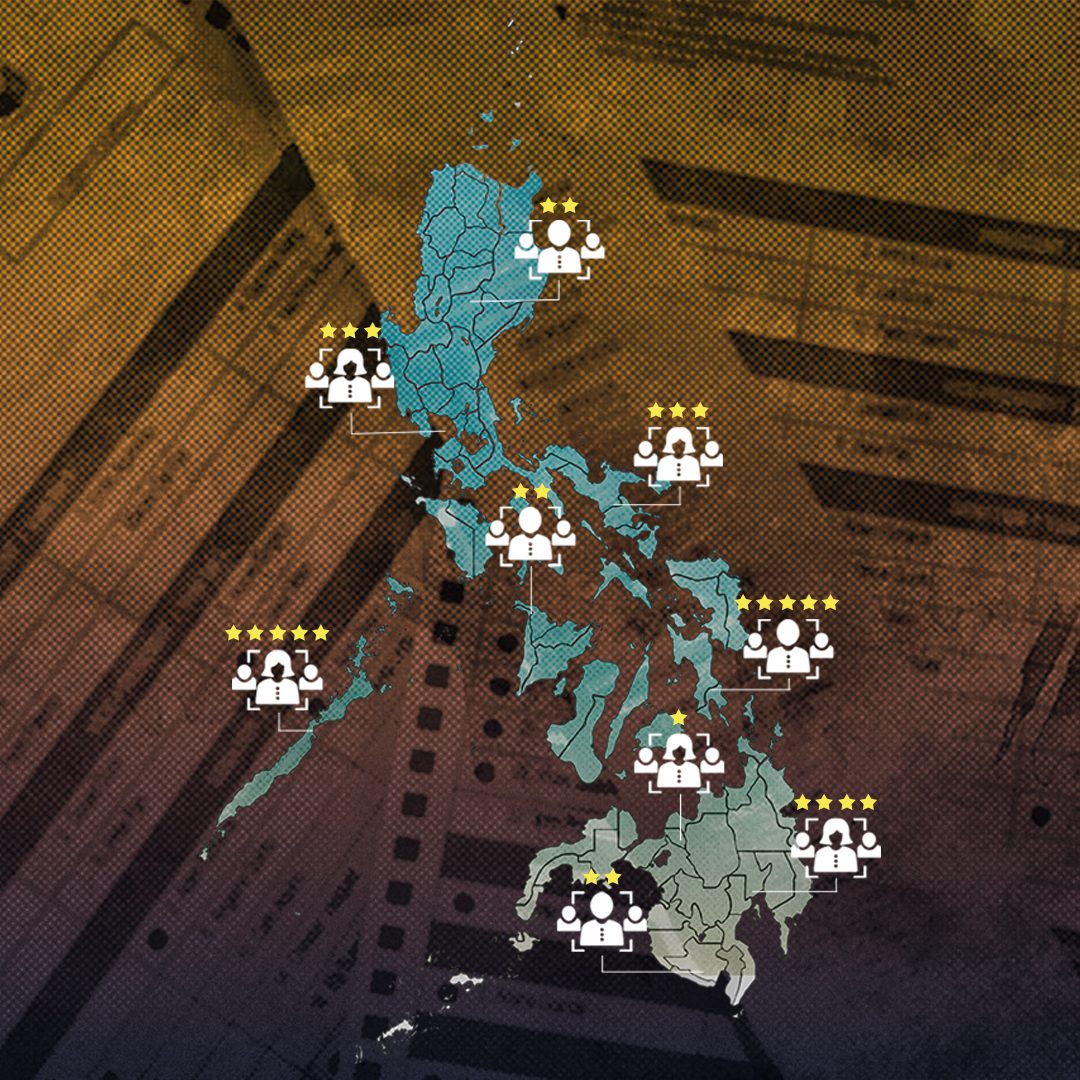

For 2019, Rappler mapped where the votes of the 51 winning organizations came from, and found that:

• Topnotcher ACT-CIS, leftist Bayan Muna, Gabriela, ACT Teachers, and Kabataan got support from the vote-rich regions of Metro Manila, adjacent regions, Central and Western Visayas, and Davao.

• Seventeen organizations got votes from the home provinces and regions of their founders or nominees. At least 5 of them really registered as regional parties.

The rest of the sectoral organizations got votes from across several regions. Assuming these votes were delivered by their local chapters or allied organizations, they indicate that organizations can only boost a national campaign if they have done focused local organizing.

Locals have their own dynamics

While the local vote bases deliver for national candidates, national influences hardly affect how local races turn out. The exceptions are when Malacañang takes special interest in specific races, and thus actively intervenes – in the form of police raids and intimidation, facilitated suspension orders, aggressive campaigning by the president, for example. This was how the gubernatorial polls in Cavite in 1995 and in Cebu province in 2013 went against projected outcomes, as it was how the reelection bid of Cebu City’s Tomas Osmeña – whom President Duterte particularly disliked20 – was frustrated.

Without such interventions, the delivery of votes is decided by the local dynamics and can go against Malacañang’s wishes.

To be sure, Duterte intended to influence the local races, but only up to where these intersected with his pet policies – the anti-drug campaign, to be specific. On March 14, 2019, two weeks before the start of the campaign period for local positions, the President read out a list of local politicians whom he alleged were into the drug trade. When the votes were counted in May, however, 27 of the 36 candidates on his narco list won, casting doubt on the power of even a very popular president to influence local contests.

The President’s party dominated the municipal mayoral and vice mayoral elections: of the 3,267 who won, 35% or 1,157 were from PDP-Laban.21 For now, however, there is no way of telling if affiliation with the national ruling party was a major factor in their victories or if they won largely on their own. The President is not exactly known as a party man. In a number of instances, Duterte endorsed competing candidates in some localities, some of them rivals of PDP-Laban bets.22

Francis Zamora, the party’s bet in San Juan, had to contend with such confusion. After endorsing him in February 2019, a month later, Duterte also raised the hand of his rival, Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino’s Janella Ejercito. Joy Belmonte joined PDP-Laban to get Duterte’s endorsement for her mayoral bid in Quezon City, but it was given to her rival, former congressman Bingbong Crisologo. Vico Sotto, who ran for mayor of Pasig City, was not a PDP-Laban member – and his rival was with the Nacionalista Party, allied with Sara Duterte’s Hugpong ng Pagbabago – but he was endorsed by the President.

Zamora, Belmonte, and Sotto won. So did Isko Moreno (real name: Francisco Domagoso), the PDP-Laban candidate in Manila. Their victories, however, like any local victories, could be attributed to their own teams’ hard and strategic work, not to their affiliation with the ruling national party or the lack of it.

Particularly interesting in the victories of Moreno, Zamora, and Sotto was the fact that they defeated scions of entrenched dynasties. In Manila, the country’s capital, Moreno beat reelectionist mayor Joseph Estrada, a former president of the Philippines. In San Juan, where Estrada started his family’s hold on power half a century earlier, Zamora won as mayor against Estrada’s granddaughter. In Pasig City, Sotto defeated reelectionist mayor Roberto Eusebio.

In the gubernatorial race in Dinagat Islands, Kaka Bag-ao won over Benglen Ecleo, a scion of the clan that had been in power since 1963, longer before Dinagat became a province.

These victories, however, were the anomaly rather than the trend in 2019. There were hardly new faces among the winners in the main positions at the local level.

Among the winners for governor, 38 were reelectionists, 17 replaced their relatives, and 26 were “new” – politicians who had held the post before or had served in other capacities.23 Bag-ao, for example, had been in Congress for 9 years (first as Akbayan representative) and initially defeated another Ecleo to become congresswoman of Dinagat starting 2013.

In Metro Manila, the winning mayors were 10 reelectionists, 3 replacing relatives, and 4 first-termers.24 These “new” ones are actually not exactly greenhorns. Moreno of Manila had been councilor and vice mayor in his 21-year political career. Zamora of San Juan, son of a longtime congressman, had served as councilor and vice mayor in a period of 9 years. Sotto of Pasig, son of celebrities, was top councilor for a term before he challenged the mayor. The 4th “new” mayor, Belmonte of Quezon City, was a longtime vice mayor. Before that, she had worked for her father, Feliciano Belmonte Jr., who had maxed out his term limits as mayor and then congressman of the city.

The city mayors who won in 2019 are all old faces: 78 reelected, 27 replaced their relatives, and 29 are returning to the posts or coming from other positions.25 Eleven reelectionists lost – and they lost to old-time politicians too.

1 The House majority, during the 17th Congress, the Speaker himself, Pantaleon Alvarez, himself wanted to lead impeachment proceedings against Vice President Leni Robredo in 2017 (Mara Cepeda, “Alvarez mulls filing impeachment complaint vs Robredo,” Rappler, March 17, 2017, https://www.rappler.com/nation/164491-alvarez-mulls-impeachment-complaint-against-robredo). In contrast, that same year, the House almost unanimously rejected the impeachment complaint against President Rodrigo Duterte (Mara Ceped, “House officially junks Duterte impeachment complaint,” Rappler, May 30, 2017, https://www.rappler.com/nation/171428-house-junks-duterte-impeachment-complaint). In 2018, the justice committee also pushed for the impeachment of then-chief justice Maria Lourdes Sereno (Bea Cupin, “LOOK: Why the House panel wants to impeach Sereno,” Rappler, March 19, 2018, https://www.rappler.com/nation/198480-sereno-articles-of-impeachment-house). In 2019, days before members of the 18th Congress assumed their posts, Duterte threatened to jail those who would try to impeach him over his refusal to keep China from fishing within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (Pia Ranada, “‘Thoughtless, senseless’ to insist on mandate protecting PH waters – Duterte,” June 27, 2019, updated June 28, 2019 https://www.rappler.com/nation/234083-duterte-constitutional-mandate-protect-ph-waters-thoughtless-senseless).

2 Rappler database.

3 LP secretary-general Kit Belmonte immediately clarified the party would “remain steadfast to its principles regardless of who wields the Speaker’s gavel [and] will continue to push for genuine democracy in the House.” Read: Mara Cepeda, “‘LP will remain steadfast to principles’ even if in House majority – Belmonte,” Rappler, June 27, 2019, https://www.rappler.com/nation/234018-liberal-party-remain-steadfast-principles-even-in-house-majority.

4 Sofia Tomacruz, “Akbayan loses House seat for first time since 1998 polls,” Rapper, May 22, 2019, https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections/2019/230844-akbayan-loses-house-representatives-seat-first-time-since-1998.

5 Anakpawis had held party-list seats in the House in the past 5 congresses, starting in 2004.

6 Rambo Talabong, “NCRPO: We won’t use ACT teachers list illegally,” Rappler, January 7, 2019, https://www.rappler.com/nation/220434-ncrpo-eleazar-says-will-not-use-act-teachers-list-illegally.

7 Carmela Fonbuena, “PH seeks terrorist tag for Joma Sison, 648 others,” Rappler, March 9, 2018, https://www.rappler.com/nation/197764-philippines-terrorist-tag-communist-rebels. The campaign period for the party-list elections started on February 12, 2019.

8 Kabataan got 418,776 in 2010, 341,292 in 2013, 300,420 in 2016, and 195,393 (based on 165 of the 167 certificates of canvass) in 2019.

9 Gabriela got 1,006,752 votes in 2010, down to 715,250 in 2013, up again in 2016, and finally 446,995 (based on 165 of 167 COCs). ACT Teachers got 372,903 votes in 2010, up 454,346 in 2013 and 1,180,752 in 2016, then back to almost the same as its 2010 votes of 394,281 (based on 165 out of 167 COCs) in 2019.

9 Gabriela got 1,006,752 votes in 2010, down to 715,250 in 2013, up again in 2016, and finally 446,995 (based on 165 of 167 COCs). ACT Teachers got 372,903 votes in 2010, up 454,346 in 2013 and 1,180,752 in 2016, then back to almost the same as its 2010 votes of 394,281 (based on 165 out of 167 COCs) in 2019.

10 Before this, Bayan Muna saw its votes rise from 750,100 in 2010 to 954,724 in 2013, which dropped to 606,566 in 2016, before it rose to 1,112,979 in 2019.

11 Akbayan got 1,061,947 votes in 2010, 829,149 in 2013, 608,449 in 2016, and 172,540 (based on 165 of 167 COCs) in 2019.

12 Satur C. Ocampo, “Two crucial stakes in May 13 elections,” The Philippine Star, May 11, 2019, https://www.philstar.com/opinion/2019/05/11/1916805/two-crucial-stakes-may-13-elections.

13 Dharel Placido, “As Bayan Muna leads survey, Sara Duterte urges voters to shun Makabayan bloc,” ABS-CBN News, April 28, 2019, https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/04/28/19/as-bayan-muna-leads-survey-sara-duterte-urges-voters-to-shun-makabayan-bloc.

14 These were Bayan Muna, Ako Bicol, Magsasaka, Cibac, Senior Citizens, and Amin.

15 APEC held seats in the House, but not during the 17th Congress (2016-2019). Coop-Natcco is an incumbent, with one representative.

16 These were Ako Bicol, Bayan Muna, Cibac, Senior Citizens, and Magsasaka.

17 An Waray, however, is an incumbent, 2016-2019, unlike 1 Pacman.

18 There were 31 party-list organizations which were endorsed by or associated with President Duterte, his daughter, and two “Davao Boys” senatorial bets. See Camille Joyce M. Lisay, “One in five party-lists competing in 2019 elections linked to the administration,” UP sa Halalan 2019, May 3, 2019, https://halalan.up.edu.ph/one-in-five-party-lists-competing-in-2019-elections-linked-to-the-administration/.

19“LIVE: #PHVote 2016 Elections Coverage, May 8,” interview by Maria Ressa, Rappler YouTube, May 8, 2016, 8:44:00 to 8:47:20, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9A0EBw-HBC4.

20To understand better how Duterte took special interest in having Osmeña defeated, read: Rambo Talabong, “Cebu City police chief Royina Garma: Mayor’s hated, Duterte’s trusted,” Rappler, October 11, 2018, updated October 13, 2018, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/213918-cebu-city-police-chief-royina-garma-profile; Ryan Macasero, “Osmeña, police clash anew: Why a checkpoint outside Cebu mayor’s house?” Rappler, April 28, 2019, https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections/2019/229099-cebu-osmena-police-clash-anew-checkpoint-alleged-political-harassment; Macasero, “Arrests, masked police heighten tension in Cebu City,” Rappler, May 12, 2019, updated May 13, 2019, https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections/2019/230386-arrests-masked-police-tension-cebu-city; and Macasero, “Masked men monitored intimidating voters in Cebu City’s upland barangays,” Rappler, May 13, 2019, https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections/2019/230407-masked-men-intimidating-voters-cebu-city-upland-barangays.

21Rappler database.

22President Duterte’s weak appreciation of party politics also affected the campaign of his senatorial candidates. Read Camille Elemia, “How Duterte’s political style is hurting PDP-Laban,” Rappler, February 9, 2019, updated February 10, 2019, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/222774-how-duterte-political-style-hurting-pdp-laban.

23Rappler database.

24Ibid.

25Ibid.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[New School] Tama na kayo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-tama-na-kayo-feb-6-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=290px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Only IN Hollywood] After a thousand cuts, and so it begins for Ramona Diaz and Maria Ressa](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/Leni-18.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=262px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] The First Mode conundrum](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-first-mode-conundrum-03232024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=283px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Free to disagree] How to be a cult leader or a demagogue president](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/TL-free-to-disagree.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Can Marcos survive a voters’ revolt in 2025?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-voters-revolt-04042024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=251px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Edgewise] Quo vadis, Quiboloy?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/quo-vadis-quiboloy-march-21-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Sara Duterte: Will she do a Binay or a Robredo?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-sara-duterte-will-do-binay-or-robredo-March-15-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.