SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Of all the things I could lose in the last few days of traveling in Japan, I certainly didn’t want to lose my wallet.

But it was nowhere to be found.

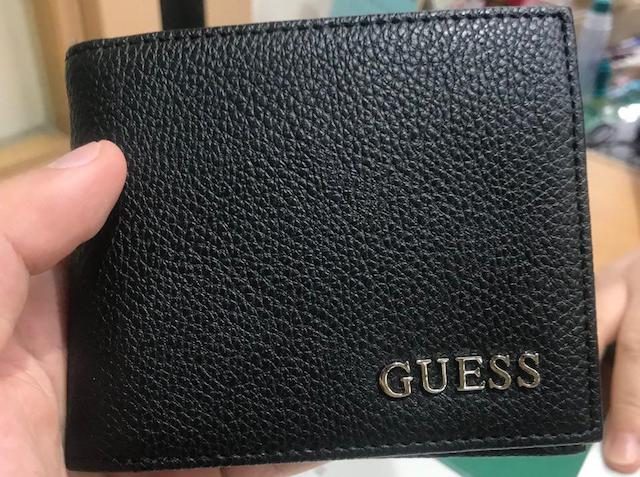

I was in Hiroshima with my mom and sister when I realized I lost it. It had all my cash and cards: credit, debit, and the travel card I needed to return to Osaka and board our plane back to the Philippines.

Naturally, I panicked.

We were staying at a capsule hostel in Hiroshima, so my initial suspicion was a thief might have grabbed it from inside my quarters while I was away. There’s a precedent for this – my GoPro got stolen before at a hostel in Amsterdam.

I pulled out the cushion of my capsule’s bed and shook it, hoping for something to fall. I repacked my travel backpack and found nothing. I ran to our hostel hostess to inquire about it, but she said none of their staff had seen it.

Already fearing the worst, I had to drag my mom and sister along with me to retrace our steps from where we were the previous night.

My mom and sister were supposed to take a day stroll in Hiroshima’s memorial park, then catch a ferry to the picturesque Miyajima island and catch a sunset by the bay. All that was scrapped for the search.

Fortunately, the hunt succeeded in under two hours, thanks to the honest and efficient Japanese. I even got my wallet back cleaner than when I lost it.

Retracing my steps

There’s really no strategy for searching when you lose something abroad. It’s just the same as losing something home. You just ask yourself, “When was the last time I saw it?”

I recalled buying bottled water at a Lawson convenience store the night before. I also bought a novel from a bookstore in bustling Hondori Street.

We first dropped by the Lawson where I bought my bottled water. The counters were manned by different cashiers already. The previous night, men rang up customers’ late-night purchases. That morning, two women were on duty.

I went straight to the woman who I thought looked Filipino. But when I asked her “Eigo okay?” (English okay?), she immediately said no. Still, I hoped that I could make myself understood with hand gestures.

“I (pointing to myself), lost (shaking my hands) my wallet (folding my palms over and over) last night (pointing to my back),” I said. She just shook her head and said no, then pointed me to the other woman, who was by then already unoccupied.

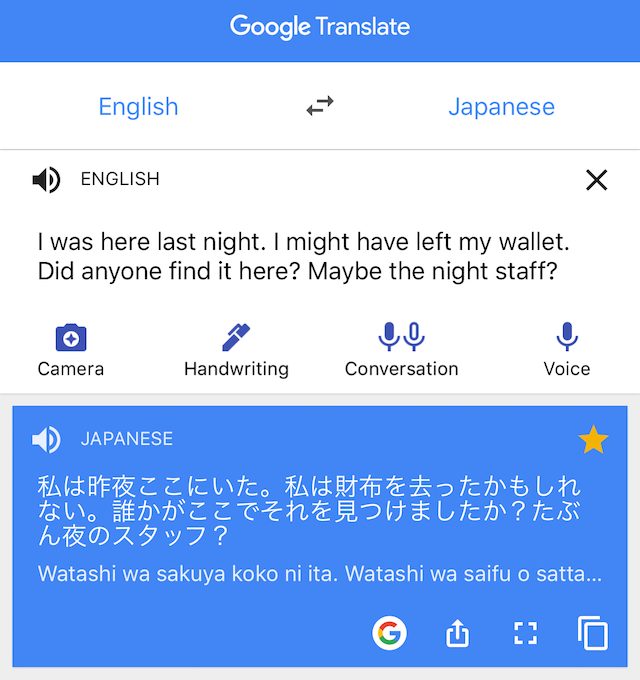

I changed my strategy. I typed what I wanted to say on Google Translate and showed her the translation written in Japanese.

She went to the back of their store, probably to check whether the night staff might have left a wallet there, but she returned with nothing.

Found, but not there

We then walked to the bookstore along Hondori Street.

It looked like the bookstore had just opened, as some of its staff were still arranging shelves. I showed the translation flashed on my phone to a woman at the counter.

She lit up, and said, “Yes!”

Finally, a sign of hope. The woman spoke with the staff who were cataloguing books behind her. One of the staffers said it was with the police, and my heart started beating faster once again.

As I was on vacation from covering the Philippine National Police, speaking with a cop was the last thing I wanted to happen.

As we were taking the 10-minute walk from Lawson to the bookstore I had read that there was also a long list of procedures I needed to follow to retrieve my wallet. These forms were also in Japanese.

While I would say I’m used to speaking to cops, this was new territory for me.

As it would turn out, I was lucky the incident happened in a place like Japan. The bookstore staffers pulled out a map, encircled where the police station is, and drew a line that I should follow to get there. They even gave me a note written in Japanese to give to the cops.

It was only a 5-minute walk to the station.

Speaking to Japanese cops

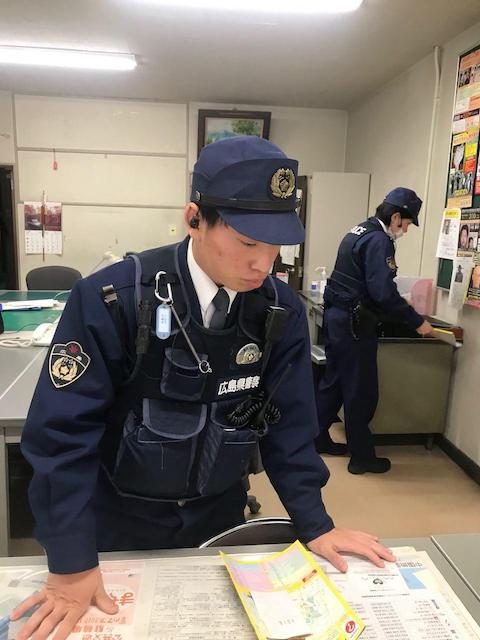

Only two cops, a man and a woman, were inside the police station when I entered. I handed my phone with the translation, and the bookstore’s note, but they seemed unable to recall a black wallet from the nearby bookstore.

As I began to worry again, the policeman spread out a lost and found form. It was in Japanese, but the cop was kind enough to fill out the form for me.

I handed my phone with Google Translate, and we “spoke” through there (thankfully I was able to quickly download a Japanese keyboard with their high-speed internet). The cop typed in Japanese and I read the English translation. I typed in English, and he read the translation in Japanese characters. This went on for around 20 minutes.

He calmly asked where I was staying in Hiroshima, when I would be leaving, what my wallet looked like when I last saw it, and what was inside it.

With the form completed, the other cop picked up the phone and made a call. She read out what the first cop wrote down to who I believe was a staffer at the lost-and-found section of the Hiroshima City police station.

After she hung up, the policewoman gave me a reassuring look and said my wallet was at the Hiroshima City police station.

It had been brought, in a span of hours, from the bookstore to the Hondori Street police station, and to their main office.

She brought out a paper stub and wrote a code. She said I only had to present it to the main station, which was also just 5 minutes on foot.

Finding my wallet

At the Hiroshima City police station, I easily spotted the lost-and-found section, as the departments were labeled with giant numbers. I walked over to an open window and handed the stub.

The woman at the counter shuffled to a drawer behind her and, in a matter of seconds, I finally saw my wallet, pulled out from the drawer and wrapped in plastic with a code printed on it.

The fine print matched my stub. She gave me a form which recorded, in Japanese, what was inside my wallet when they found it.

I inspected it and found it cleaner. The cops had flattened and arranged the pesos and dollars I had haphazardly placed inside my wallet. However, I found no yen.

Someone might have stolen it while the wallet was being brought from the bookstore to the police station, I thought.

Before I could ask the woman about it, she said they recorded how much yen was inside and took it out for safekeeping. She placed a small plastic tray stacked with new and crisp yen bills in front of me.

I erupted into celebration then and there, showering the woman with my most heartfelt “Arigatou gozaimasu!” (Thank you!)

With time to spare, we were even able to go to the Hiroshima Castle and walk around Hondori more to shop for pasalubong.

While I was in a state of panic the whole time, there was a part of me that kept on saying, “You’re in Japan, you won’t lose it here.”

I guess this now-proven assumption was borne out of days of experiencing the kindness and efficiency of the Japanese.

The trains arrive and leave on the dot, with everyone falling in line to exit and enter. Priority seats in buses are left vacant, even during packed rides, for the elderly and the pregnant. Cleanliness is a sacred rule in public spaces. The country consistently records one of the lowest crime rates in the world.

I wish I could say the same back home, but we, as a country and as a people, have a long way to go.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.