SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] How well do you know the candidates?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/6687DA508BB84C33AE4C4C6561E41BB4/how-much-do-you-know-candidates-may-9-2019.jpg)

This is a #PHVote newsletter sent to Rappler subscribers on May 6, 2019.

I am Gemma Mendoza, head for research, partnerships, and strategy at Rappler. I lead the team that gathers data for our election content and executions. This same team is also in charge of monitoring and fact-checking false claims circulating on social media.

If you’re one of the 61,843,750 registered voters in the Philippines, you are expected to cast your vote on Monday, May 13, between 6 am and 6 pm.

Have you made your list of who to vote for yet? How well do you know the people who are running for public office? I hope you know better, because I sure don’t know enough. And it is not for lack of trying.

Since Rappler was born, we have made it a point to produce content every election season that would help voters get to know the candidates, their track record, and positions on issues. We organized debates, public fora, and candidate interviews. We also produced explainers to help educate the public on how the election system works.

This season, we profiled all 62 senatorial candidates and listed down the nominees of all the 134 party list groups. It is far from enough. Unfortunately, we never got round to looking deeper into the party list nominees – over 727 in all. We did find that at least 46 party-list groups participating in the 2019 polls have at least one nominee linked to a political clan or a powerful figure in the country.

I wish we could do more. But it has not been easy work. There is just so much to do and so little time to do it. And for some reason, it gets harder every election. It does not help that, as we are doing all of these, we have also been fact-checking an unprecedented amount of disinformation circulating on social media.

The synchronized Philippine national and local elections are perhaps among the most massive political projects a country ever undergoes every three years.

How massive is this project? For starters, this 2019, votes will be processed by over 85,000 vote counting machines in over 36,758 polling places around the country. This excludes the 83 foreign posts, which have been conducting overseas absentee voting in various cities around the world.

A total of 43,677 candidates are vying for 5,567 national and local contests or over 18,000 available elective positions. (READ: 2019 local elections, in numbers)

Every Filipino voter is expected to select nearly 3 dozen names out of a list of over 350 names in around 1,700 location-specific ballots.

From the point when these candidates submit their certificates of candidacy to election day, we only have 7 months to really get to know them.

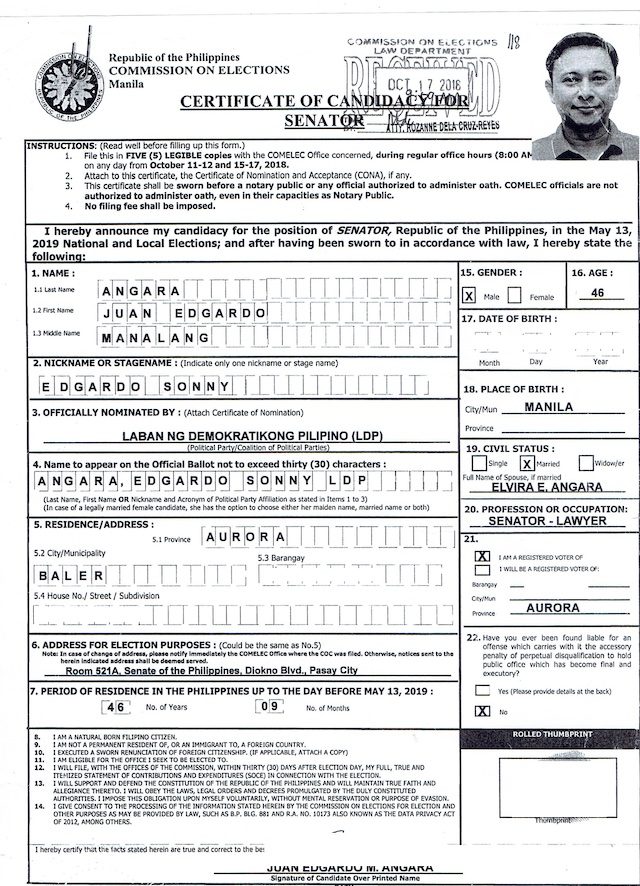

Getting the names of those who are running alone – and matching the names with records of actual unique persons we know – is already a challenge. In the Philippines, unlike in more developed countries, candidate filings are not released in open formats that can easily be processed and used for populating or querying databases. They are released in the form of scanned documents, which, every data analyst knows, are a pain to process and encode.

And even when you get them, the certificates of candidacy hardly say anything about the person who filed them: only basic information, such as full name, birthdate, address, etc. Nothing is said about educational attainments or track records of candidates. Tragically, we have more stringent requirements for people seeking janitorial and clerical positions than people who want to run for public office.

If you go through the effort of finding more information, you will find that government agencies who serve as repositories of vital databases tend to make the process of securing information about people running for public office so hard.

For instance, in the newsletter he sent last week, Michael Bueza, one of our researchers, emphasized the importance of assets and liabilities disclosure statements of public officials. While these documents, as mandated by law, are readily released by the Philippine Senate and the Office of the Ombudsman, every year they are difficult to acquire for members of the House of Representatives. (READ: New House rules make it harder to access lawmakers’ SALNs)

The same goes for pending cases. We tried to get the records of cases of candidates running for public office that are pending before the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan. After repeated requests submitted to the court en banc, we have yet to get an updated version of the data. We did manage to list down Senate hopefuls who are facing cases, complaints, probes.

It does not help that candidates have adopted this practice of adopting weird names for listing in the ballots other than their real legal names. For instance: Gil Acosta, who is running for congressman of the 3rd district of Palawan, decided for some reason to use ACOSTA, KABARANGAY JR as the name to be listed in the ballot. Meanwhile, senatorial candidate Romulo Macalintal uses MACALINTAL, MACAROMY as his ballot name.

All of these peculiarities mean that trying to automatically query for more information about people running for public posts becomes harder.

One senior high school intern, who was tasked to get information about members of the House of Representatives, had this insight: “These candidates do not want us to get to know them.”

It does not help that many candidates avoid attending debates, where their promises can then be scrutinized. Many prefer to dance and sing, as if the government offices they are applying for are part of the entertainment industry.

All of the above, sadly, leave voters little choice but to treat the electoral process as practically a lottery of sorts. We choose the name that we can recall the most, the ones who belong to the old political clans, or the candidate that we find cute or approachable.

And then we leave everything else to the mercy of the gods. – Rappler.com

Here are #PHVote content you shouldn’t miss:

- For the list of national and local candidates and additional data about them, visit rappler.com/votewisely.

- For our latest election stories, visit rappler.com/phvote.

- Are you a first time voter? Learn how to vote by viewing our step by step guide.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.