SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

I knew it would be a night I would keep sacred as soon as I stepped out of the car.

It was evening and Gateway Mall in Cubao wasn’t just buzzing with commuters. Teens and twenty-somethings paraded in packs, donning garments that either screamed “Go on and mug me” and “It’s pride month again,” attracting glares from office workers itching to go home.

They wore silver jackets, denim jackets, flower-embroidered black dresses, sequin-studded heels, brown dress shoes, electric blond bob-cut wigs, pastel eye shadow, dark lipstick, light lipstick, and giddy grins.

They walked and crossed non-existent pedestrian lanes slowly, but talked fast. They emerged from all directions, but were heading towards one building, the New Frontier Theater, where dozens of followers of what appeared to be a color-blasted cult spilled out onto the streets.

I tried to blend in with the crowd with my black V-neck T-shirt, black Uniqlo pants, and an electric pink sweater, which my friends later judged as “very gay.” At least for tonight, I could get away with it in my country that has so far denied the rights of my community to marry. She was coming, and I must not tremble.

It was only Wednesday, but no matter. Like the crowd, I abandoned all my troubles and dove into the 2,000-strong procession to her “Kingdom of Desire.”

Carly Rae Jepsen was in Cubao.

I know not everyone would understand the reasons behind our near-spiritual obsession, so let me tell you the story of mine.

How I found her

Perhaps like everyone else, I heard her first through that song, “Call Me Maybe.” It was an instant hit, and she was, as many other stars in early 2010s, a viral sensation.

It was 2012, and I was still an acne-assaulted high school gay boy aching to come out of the closet. Liking a bubblegum pop song guaranteed scrutiny about my sexuality.

I found the track too sweet for my taste, too girly to be cool for boys, while I discreetly nodded to its rhythm and stole sustained glimpses at the blue-eyed Canadian in the music video.

That was Carly Rae Jepsen then. Her art was but a fleeting stimulant, quickly buried as it was launched to fame.

Then 3 years later, she came back storming with “Run Away With Me.” As a stressed queer probinsyano still struggling in sophomore year in a Manila university, the track had everything I needed: pure and blissful escape.

The saxophone took me away, constructing in my mind my yellow-brick road that allowed me to flee from the moment, from the sadness, and all the crushing pressure. I imagined she was smiling.

“I wanna go, get out of here, I’m sick of the party, party. I’d run away. I’d run away with you,” she sang.

The next year, I studied for a semester abroad and was chilled by the winter to unbearable homesickness. I found warmth in the same song thousands of miles away from home, and continued to seek it out after I returned home.

“Run Away With Me” freed me of the world’s weight when it pressed on me in bed in the morning, and I found myself humming it when I walked home feeling defeated. It has become my inevitable song for escape.

And this was only one track.

Why she resonates

So potent are Carly Rae Jepsen’s songs to me that when friends question my obsession, my eyebrows would furrow. How do I begin?

First thing to know is that the power of Carly Rae Jepsen’s craft as a musician lies more in her writing than her singing. Carly Rae Jepsen does not possess the powerhouse voice box of great balladeers like Adele, Christina Aguilera, or Sarah Geronimo. Her magic springs from the same stream as Taylor Swift, Lana del Rey, and Armi Millare from Up Dharma Down.

For every dozen-song album she has released, she has composed 200 other songs that did not make the record’s cut. Hers is a repertoire that does not require the sky-high range of a choir’s soprano, but her music can send you digging up emotion-charged memories in the recesses of your mind. And practically speaking, when she sings, it’s easier to sing along with her without being afraid of faltering in the chorus.

Carly Rae Jepsen writes about love. She tells the stories of its facets that are simple and relatable. She wrote about looking for love. She wrote about finding love, not finding it at all, and finding it but losing it eventually. She wrote about loving for the lust, and loving for the real reasons. She wrote about not being enough, and being too much. She wrote about finding love in loving herself.

She writes without words, images, and narratives that confuse. In every song, she writes of a lover and a beloved. For many, that is enough to believe in her music.

She has mostly dedicated her most moving opuses to those trapped in lovelessness, which I believe is the reason that she also resonates deeply with the queer community – people who have historically been robbed of desires and the right to love. We are a people who, for generations, have been in need of an escape.

The night

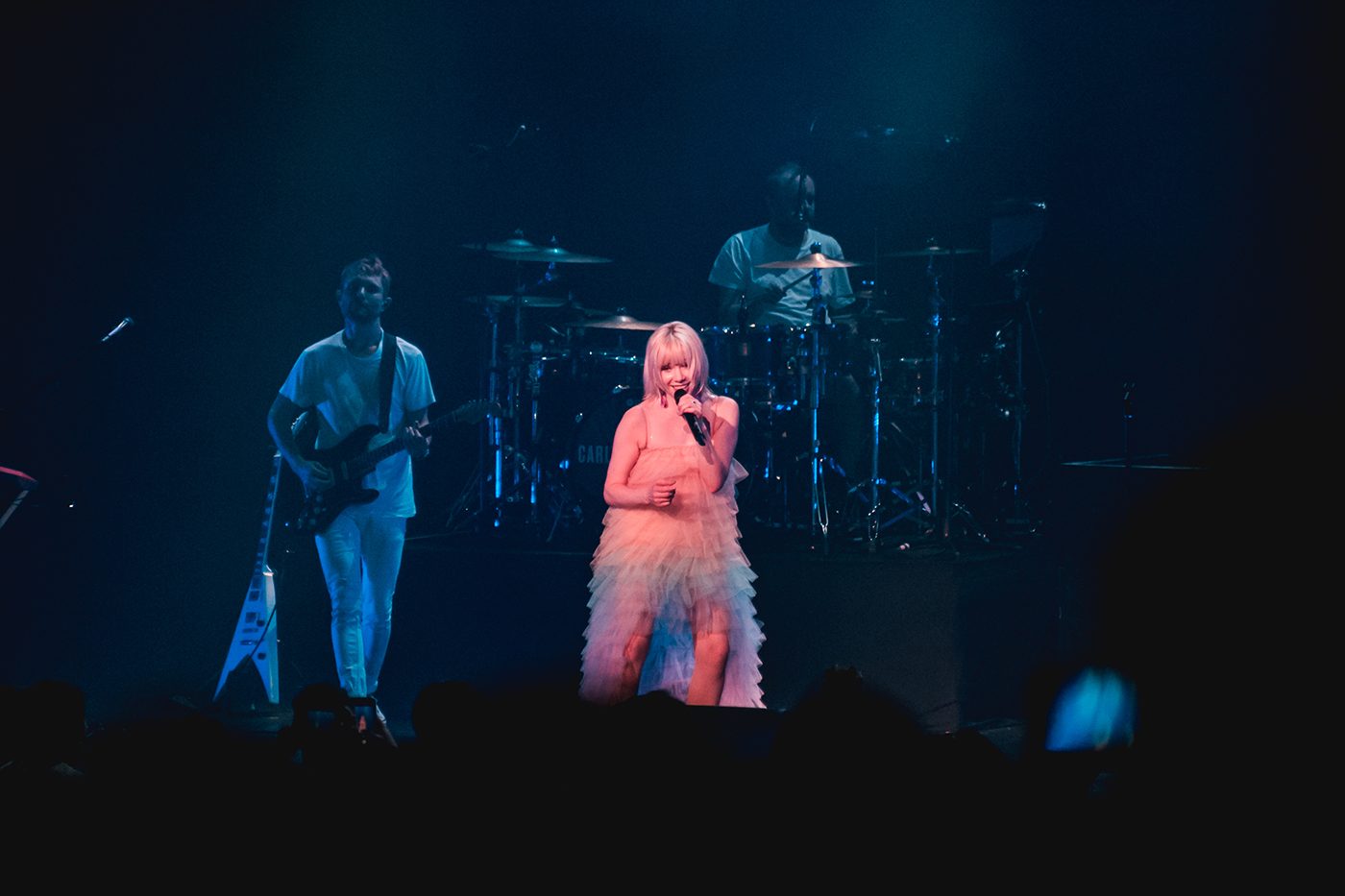

Carly Rae Jepsen entered in a cloud of a rainbow-shaded tulle, sashaying on a pair of metal-heeled beige boots to the beatless cheer of an exploding crowd.

Here was a woman who has written masterpieces to be adored for decades, still boxed in by many as the girl who went viral for one song, but has now emerged as a “gay icon.”

Beside me were my closest friends shaking after seeing her finally emerge, their hearts also brimming with memories tethered to her songs.

Only a dozen dark blue lights lent their glow, drawing her silhouette. Her 4-piece band strummed and pressed their chords. The LED backdrop flashed a star exploding. Then smoke.

The scream of the crowd was already deafening. We bid goodbye to inhibition and reveled in the safe space. I already began losing my voice screaming her name even before her first note. It’s understandable why we have been jokingly described as a crazed cult.

She held the black microphone in its stand, looked down, and started the long-awaited night. For two hours, we were in heaven. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.