SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Months before I completed my journalism degree, a photojournalism professor asked me what I planned to do after college. Before I could reply, he said in a stern, though fatherly tone, “Mabubulok ka sa diyaryo (You will rot in the papers).”

He was working for a newspaper and had colleagues who had lost their youth in an industry that didn’t take care of them well enough to retire comfortably. His words conjured thoughts of a life term. And bottled bagoong.

I did not even need the warning. At that time, I had already gone through two consecutive summer internships – in my sophomore year at a local daily; the following year at an international wire agency. In both instances, one experience bolstered by the next, I resolved that I would not work in media. I didn’t have the personality of a journalist, I thought then.

I had an inquisitive nature, a quick grasp of current events, and wrote clear and concise stories but I couldn’t picture myself elbowing my way to a subject trapped by men and women, locked in a shouting match. I also had selective stage fright. I had been an introvert from my teen years onwards, but I recited in class and had no problem giving oral reports throughout my academic life. Despite this schoolroom practice, the mere thought of asking questions at a press conference kicked my last meal to the back of my throat.

It didn’t help that on the first day of my internship at the Manila Chronicle, my minder was nowhere in sight. I might have met him only once or twice the whole month I was assigned to the Senate, then housed at the old building where the National Museum now stands.

The internship program was a three-unit course that I had to pass, and I did my best to overcome my timidness. I introduced myself to the media officers for proper accreditation, and checked the schedule for that day and the rest of the week. I read newspapers to keep abreast of the latest developments. I followed reporters who left the press room to wait outside closed-door hearings. I had no tape recorder then and relied entirely on my notes. I couldn’t remember if I ate anything that day but I might have drunk some water.

The whole time, I felt like a non-swimmer hurled into raging waters; sink or swim. It was a daunting first lesson in self-sufficiency.

The second month of my internship was at the House of Representatives. Had I been assigned to my new minders earlier, I would have had a better first impression of media work. Crien Pastor and Nona Ocampo were ideal mentors: patient, hands-on, accommodating, and spared time to critique my copy.

In both houses of Congress, I attended all the committee hearings I could fit into my day and labored through proposed bills and sessions. I arrived early and went home late. I only had time for lunch and toilet breaks. I worked through the summer and skipped important family activities for news coverage. It was a preview of the life of a journalist, and I was almost certain I didn’t want it.

In my second internship before my senior year, I was assigned to Agence France-Presse. I tagged along my designated minder to events. The highlight was a 60-second phone interview with US Ambassador Nicholas Platt on a US facility that had been blown up by the NPA.

It was another summer of firsts – first Labor Day rally to interview militant groups about their wage hike demand, first international summit on children’s rights for which I was generously given my first by-line, first incidental appearance in news footage (behind Raul Manglapus). I would often nearly trip over another reporter as I moved with a pack of journalists interviewing a reluctant, moving subject. The industry was fast-paced and exciting – a nice summer experience to recall on tedium-dogged days – but most of the time I just wanted to sit down and watch them all pass by and disappear in the horizon. I never really thought I could ever fit in.

Convinced that I was better suited for further studies, I spent the months after graduation gathering application forms for possible scholarships, but I never accomplished any of them. Freed from the clutches of school, deadlines, and most of all, summer internships, I could finally devote myself to my true passion – creative writing. I began developing short stories in Filipino and English.

A few months into my unemployment, my sister, Mariel, met a former theology professor who suggested that I apply for a position as an associate editor of the Philippine Human Rights Monitor, a publication of the Ateneo Human Rights Center, which left some room for my other pursuit.

I had been in that job for only a few months when my well-meaning brother-in-law, Terry Capistrano, gave me the phone number of the late Caloy Santos, the shipping editor of the defunct Manila Chronicle. There was an opening in his section.

I didn’t want to disappoint my brother-in-law and my journalism professor, Rene Pastor, who was expecting me to join his industry. I was the only journalism graduate in my batch (from four at the start of the program). I should at least practice what I learned and trained for. I could always quit later, I thought then.

I had no reason to quit, though. It was better than I expected, even as I circled the Port Area for interviews with the shipping sector and government agencies overseeing the industry. I went to work in jeans and was not on the clock. I developed sources, and I think, more important, friendships with my co-reporters.

The shipping beat was covered by only two other newspapers, the Business Star and BusinessWorld. I gathered material for mostly enterprise stories that I would schedule for submission over the week, giving me a flexible schedule that accommodated a Masters degree in Creative Writing at UP, which was offering it for the first time. (It would take me 10 years to complete it, but that’s another story.) A year into my degree, Dr. Butch Dalisay told me that Teddyboy Locsin was opening a new daily and that I should apply so I could put my newswriting skills to better use. (He urged his CW students not to give up their day jobs, for practical reasons.) He endorsed me to the managing editor. I was scheduled for an interview but I missed it and was too embarrassed to get another appointment.

Months later, Today’s lifestyle section asked for a short story submission upon the recommendation of Dr. Dalisay. I personally brought a hard copy of my story to Today. On my way out, I bumped into a former officemate who worked there. He presumed I was an applicant and before I knew it, I was in front of the managing editor who still remembered my name. Stunned by the speed of developments, I couldn’t tell him that I wasn’t there for a job. But having been mired in a beat that didn’t challenge me, I guess part of me wanted to explore the opportunity. I was hired as a news features writer.

I never carried out my original job function because I was assigned as a back-up reporter in Malacañang, an assignment described by others as a “quantum leap” in my case since I had handled only minor beats. (I would later find out that no other reporter wanted the assignment.) I was supposed to be confined to economic issues in the Palace, but this soon extended to all other issues emanating from Malacañang, which could be as diverse as goods sold in a public market. On the same day, I would write about the country’s GDP growth, salmonella-infected balut, and the secessionist movement in the Southern Philippines.

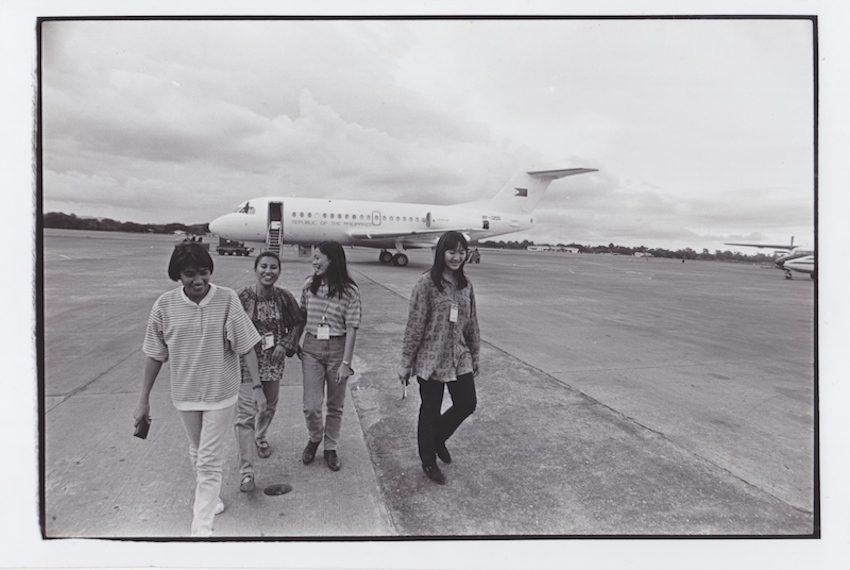

At the Palace beat, I developed lasting friendships while fighting off sleep at Villamor Air Base Base Operations to catch a pre-dawn Air Force flight to anywhere from Aparri to Basilan where President Fidel V. Ramos would have a full day’s activities, or while staked out indefinitely at the Palace lobby, waiting for officials to walk down the stairs on rare slow news days.

In time, I would learn how to phrase questions that would get me the answers I wanted, and without ever departing from my calm nature – initially, in the timid voice that I found so unsuitable for a media job. I would still prefer one-on-one interviews over asking questions at press conferences, especially televised briefings, but I would have to do it because it’s part of the job.

When Today was dissolved to merge with Manila Standard, I became unemployed again. It was an opportunity to start fresh, but by that time, I was already the full-fledged journalist I never thought I would be, nurtured by terrific editors like Chuchay Fernandez who made me love the profession. When BusinessMirror was launched, steered by my former Today editors, I jumped onboard, again.

Having spent over a decade in the same beat, I often found myself feeling too comfortable. I wondered if this was the “sweet trap” I heard some people “complain” about – staying in a job just because everything had become so convenient and predictable, and change would only bring you back to the starting point of a long race already run.

I might have felt like an ant caught in a self-replenishing sugar bowl. The hours were often long and stressful and there were times during the past two administrations when I asked myself whether it was worth it. In times of doubt, a tiny but commanding voice inside my head would say that all the hard work and anxiety were always cancelled out by enduring friendships, the ease of navigating even the most complex issues with a constantly updated mental map, and the natural, though addicting, high one got in documenting, witnessing, and even participating in history as it unfolded.

Perhaps to appease my literary side, that same bossy voice would tell me that I could later cannibalize my experience, thinly disguised as a political novel. This thought would enervate me when I got exhausted just by the prospect of running after another story. At some point, I knew it would be inevitable to move on to the next phase of my “accidental” career: the editorial desk.

Most beat reporters resist desk work because it would pluck them from the thick of the action, only to be lodged into the humdrum of office life. Who wants to improve somebody else’s copy and not get any public credit for it? But at the right moment, at the right time – with some gentle persuasion – it wouldn’t be difficult to reconsider. At least, that’s what happened to me. Now, here I am. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[EDITORIAL] EDSA or no EDSA, padayon](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/02/animated-EDSA-panatang-makabayan-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=90px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Be The Good] Talking AI between ridge and reef](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Talking-AI-between-ridge-and-reef.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=270px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Filipino journalists to China: Yes, we are trouble](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-wps-march-tension-2024-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] Journalism is debate](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/journalism-debate-march-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=447px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Dapat makinig si Marcos kay UN special rapporteur Irene Khan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/animated-un-marcos-human-rights-elcac-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=327px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[ANALYSIS] Investigating government’s engagement with the private sector in infrastructure](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-gov-private-sectors-infra-04112024-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Newsstand] The media is not the press](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-media-is-not-the-press-04132024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=281px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.