SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

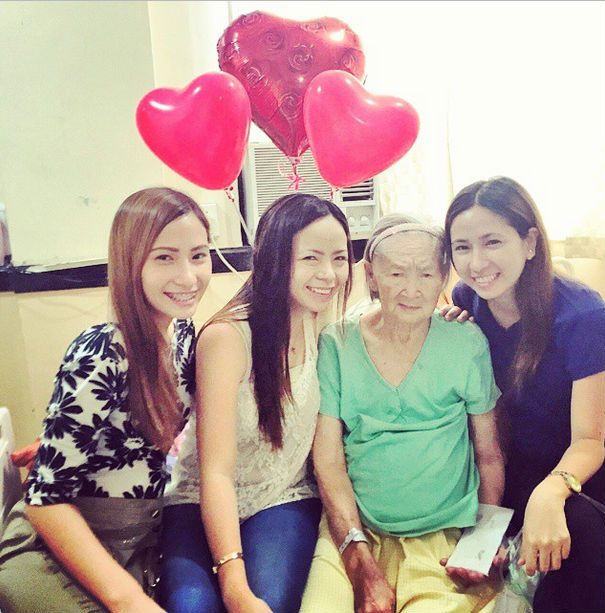

It’s very painful watching someone you really love go through a difficult time aging, especially when that person often can’t remember your name.

It was only 8 years ago when she was still full of life. Laughing and talking from morning until the next sunrise.

You see, my lola Ines Gajudo was the type of woman you couldn’t keep in one place. She’s been everywhere from the Holy Land to Egypt, Niagara Falls, and San Francisco. She has the looks of a movie star and the personality of a veteran politician. But she was no politician. To me, she’s just lola.

Growing up in the United States, my summers were not complete without lola Ines. Sometimes she’d come over our house while I was still asleep. My aunts and uncles would be in the kitchen, while she’d be whipping up what we knew was lunch for the day.

I didn’t need my alarm clock, the smell of the vegetables, herbs and spices boiling in the kitchen was enough to draw me out of bed. I would run out of my room to find out what was going on out there.

Working mother

Lola was not just a mother of 12, she was also a breadwinner of the family. Legend has it that she was one of the first – if not the first –woman to drive a car in her province. And she had to. She had a business to run and 12 mouths to feed and send to school.

Strong lola

Into her 70s and 80s, lola remained a strong, beautiful and independent woman. She was so independent that she would often refuse my help when I would reach for her hand walking down the stairs. “Kaya ni nako, dong,” she’d say. (I can do this.)

I learned about my family’s colorful history through her storytelling. It was in long car rides from one relative’s house to another, where she’d tell me about where the Del Mars – her family – came from; starting from Spanish times in Bohol and Cebu, up to World War II and today. I wouldn’t even turn on the car radio because I knew that there wouldn’t be a minute of silence if lola was riding with me.

I miss the way she’d pinch my nose when I’d tease her about something and the way she’d laugh at my stories of the day and tell everyone about it.

Signs of aging

Things are different now, though. Lola suffered a stroke in 2009 and her condition just got worse from there. She started to have a hard time walking; her behavior started changing, she would get irritated easily, which is unusual for those who knew her. All signs pointed to dementia.

I was living in the US when this happened and in my 4th year of undergraduate studies, so I was not able to see her condition change.

So when I came to visit her for the first time in 2013, the year I moved to the Philippines, I was in for a shocker. I walked into her room and I saw this skinny, frail old lady lying in her bed. It was my lola Ines, but I was not used to seeing her like that. I hated seeing her like that.

Normally, she would always be happy to see me and greet me with a big smile, hug, or a kiss on the forehead and a sniff on my neck while offering me a box of chocolates. Her caretaker asked her, “Kaila pa ka ana, la?” (Do you know who that is?) She looked at me and shook her head.

That just broke my heart. I had to step outside or she would have seen me break into tears. She would not tolerate seeing me crying before.

If she ever caught me crying, she’d stroke my hair or grab my hand and gently say, “Don’t you cry, Ry! Ok? Crying is only for babies. You have to be strong.”

From strong and independent, she became weak and helpless. She’s been around the world by herself, but nowadays she cannot get outside of her room without the help of her caretaker and is hardly in the mood to go out. While you couldn’t get her to keep quiet before, I now have to put my ear to her lips to even hear what she’s saying – and I’m the one doing most of the talking.

So when I heard she was hospitalized for a week with pneumonia, I became very worried, I knew I had to get to Cebu to see her.

I had always imagined lola would still be telling her stories until she was 100. And that she’d still be cooking her adobo or tilapia for me and would still be refusing my help down the stairs. So watching her age this way is especially painful.

She’s now on a dozen medications. Most of the time, instead of warm smiles she’d just give me blank stares. I grabbed her hand to try to remind her of what it felt like when she used to grab mine, but I wouldn’t feel her grab my hand back. It’s just not the same anymore. I know it’s not her fault though, it’s her condition.

I spent the day reminding her of the stories she used to always tell me, regardless if she wanted to listen or not – such as the time she visited the Holy Land, how uncomfortable it was to ride a camel in Egypt, and how “cold” it was in Niagara Falls.

I asked her about where she grew up in Bohol because I haven’t been there since I was 13, and asked if she remembered how it looked like. And the more I talked to her the more it seemed like she could actually recall these memories. She even said of her lot in Bohol, “Gamay ra man.” (It’s small)

While I was talking she suddenly told me “husto na” (that’s enough). I don’t know why. Was she just grumpy? Or was it because I was reminding her of who she used to be, and it pained her so much that she couldn’t do those things anymore.

By 10 pm on the day I spent at lola’s, it was time to go to sleep. Her caregivers carried her to her bed, but before she went to sleep I saw her signal me with her hand to come over.

She whispered in my ear, “Mangadto ta sa Bohol” (let’s go to Bohol). And suddenly she had the will to go out again. All it took was a little time and love. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.