SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – When a boat hiding dozens of endangered scaly anteaters or pangolins was found parked in Palawan in 2013, officials discovered most of the animals came from other parts of Southeast Asia, not from the Philippines.

It seemed the Chinese fishermen manning the boat had been going around the region, collecting pangolins at key points. Palawan was to be another collection point where locals carrying pangolins endemic to the island would be added to the boat’s cargo.

But the Philippine Coast Guard got to the boat first.

Asian pangolins, two species of which are endangered, are among Southeast Asia’s most illegally trafficked wildlife.

In China, they are a favorite ingredient in traditional medicine and their meat is considered a delicacy. Recent findings show that their scales are even used as a precursor for the drug methamphetamine.

While a capture is always cause for celebration, Philippine biodiversity chief Theresa Mundita Lim wonders if the boat could have been stopped even before it began collecting pangolins.

“If there was a strong network, there would have been an initial action at the regional level as soon as the boat entered Southeast Asia,” she told Rappler.

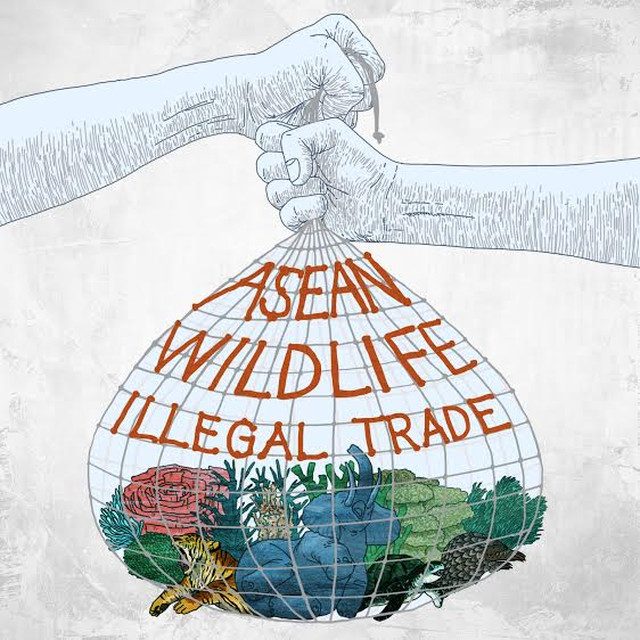

As the 10 countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) gear up for economic integration, anti-trafficking experts are keeping an eye out for loopholes that will allow illegal wildlife trade syndicates to benefit from the lowered trade barriers and smoother flow of goods and services in the region.

The map below shows the route of illegal wildlife products. Click the symbol on the left-most side to go through the routes of 4 different products.

LEGEND: Countries in green are source countries (where the goods are harvested from the animals), countries in yellow are transit countries (where the goods pass through), and countries in red are destination countries.

Through integration, countries are weaving closer ties among themselves, but the still rampant illicit trade spells a battle the countries need to wage within their borders.

Web of cooperation

When Lim presented the ASEAN Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN) to Interpol in 2012 in the agency’s headquarters in France, it had been among the first working regional networks of its kind.

ASEAN-WEN is a web of government agencies from all Southeast Asian countries created to facilitate coordination to crack down on illegal wildlife trade.

“We need a regional response because the crime is also regional, transboundary in scope,” said Lim.

ASEAN-WEN was created in 2005, a year after ASEAN leaders committed to strengthen law enforcement against wildlife crime.

ASEAN has become a hub for the illicit trade because of its wealth in rare flora and fauna, and its close proximity to the biggest market for trafficked wildlife: China.

Southeast Asia’s illegal wildlife trade could be worth as must as US$8 billion to $10 billion a year, according to a Brookings Institute report. In 2005, it accounted for 25% of the global trade.

Since its creation, ASEAN-WEN has evolved, now counting the US, China, Africa, Interpol and counter-trafficking organization Freeland, as its partners.

Freeland credits ASEAN-WEN with the 11-fold increase in confiscated wildlife contraband since 2008. Since then, ASEAN governments together confiscated over US$90 million in illegal wildlife and arrested 1,335 suspects.

It also now has an office in Bangkok, Thailand, sustained by funds contributed by each ASEAN country. The office acts as an information hub with help from Freeland.

After 39 years working in the Bureau of Customs, Nicomedes Enad has first-hand experience of how ASEAN-WEN has made his job easier.

Enad, now retired, was chief of the Customs’ Environmental Protection Unit. He’s seen his share of smuggled elephant tusks. He recalls a time when his team had to deal with rare spiders hidden inside a stuffed toy bear.

He said one major improvement after ASEAN-WEN was the strengthened linkages among countries.

“There is now an easy transfer of information. You have established already the focal person for each country so through email, any other form of information, you can easily contact them,” he told Rappler.

Lim, who was a founding chair of the ASEAN-WEN, said the network also provided the political will for agencies within governments to work together.

Instead of the Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB) doing everything, the requirement of the network for a national task force means that the BMB can call on the help of the police, Coast Guard and Customs.

Though this is what is supposed to happen anyway, there’s something about an international mandate that kicks officials into action more than any local law can.

Agencies of one country are also able to coordinate directly with their counterparts in another country.

“The police in Thailand have a network with police here. Before, it would just come from us. We’d tell the police. But we noticed the action is different when they are the ones coordinating with each other. They feel that they understand the situation amongst themselves in enforcement,” she observed.

Falling through the cracks

But ASEAN-WEN needs to keep up with the challenges ahead, including more sophisticated syndicates and the economic integration.

One major gap that needs to be filled is regional enforcement capacity, said Lim.

The network has to do more than strengthen national task forces and facilitate information-sharing.

“We are able to give each other data and tips but to be able to capture criminals and confiscate at a regional scale means we need to strengthen transboundary enforcement,” she explained.

This means countries should be able to alert each other even as illegal wildlife is about to cross borders, not when they are deep within one country when they are harder to trace.

Enforcement agencies should also be able to carry out joint operations with their counterpart agencies leading to arrests and confiscations, said Lim.

Another gap is the uneven levels of enforcement and varying laws on wildlife crime across ASEAN countries.

“The trade route just shifts. If it gets hot here in the Philippines because we strengthen enforcement, the syndicates will just shift the route to Thailand or Vietnam. So there needs to be coordination or else the transit point will just hop from one country to another,” she said.

Penalties and fines for illegal wildlife traders need to be standardized across the region so that criminals don’t flock to “weak spot” countries.

In the Philippines, killing a critically-endangered species could land you 6-12 years in jail, while the same offense in Cambodia can cost you only 1-5 years of jail-time.

But for Enad, ASEAN leaders also have to focus on one of the driving forces behind the region’s rampant illicit trade: poverty of communities living near the habitats of the heavily-traded species.

“The first reason is poverty. The money involved in illegal wildlife trade is big. If there was no money, it wouldn’t be happening,” he said.

In the Philippines for instance, local fishermen are often the first to gather rare corals, fish or turtles for selling to middle-men.

Fisherfolk are the poorest sector in the Philippines, with the highest poverty incidence at 39.2% as of 2012.

The ASEAN illegal wildlife trade is a tough beast to beat, but the next years will determine if the 10 member-countries can work together to protect their shared treasure. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.